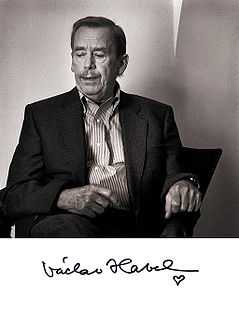

Václav Havel

| Václav Havel | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st President of the Czech Republic | |

| In office 2 February 1993 – 2 February 2003 | |

| Prime Minister | Václav Klaus Josef Tošovský Miloš Zeman Vladimír Špidla |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Václav Klaus |

| 10th President of Czechoslovakia | |

| In office 29 December 1989 – 20 July 1992 | |

| Prime Minister | Marián Čalfa Jan Stráský |

| Preceded by | Gustáv Husák |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 October 1936 Prague, Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic) |

| Died | 18 December 2011 (aged 75) Vlčice, Czech Republic |

| Political party | OF (1989–1993) |

| Other political affiliations |

SZ supporter (2004–2011) |

| Spouse(s) | Olga Šplíchalová (1964–1996) Dagmar Veškrnová (1997–2011) |

| Children | None |

| Alma mater | Czech Technical University Academy of Performing Arts |

| Signature | |

| Website | www.vaclavhavel.cz www.vaclavhavel-library.org |

Václav Havel (Czech pronunciation: [ˈvaːt͡slav ˈɦavɛl]; 5 October 1936 – 18 December 2011) was a Czech writer, philosopher,[1] dissident, and statesman. From 1989 to 1992, he served as the first democratically elected president of Czechoslovakia in 41 years. He then served as the first president of the Czech Republic (1993–2003) after the Czech-Slovak split. Within Czech literature, he is known for his plays, essays, and memoirs.

His educational opportunities limited by his bourgeois background, Havel first rose to prominence within the Prague theater world as a playwright. Havel used the absurdist style in works such as The Garden Party and The Memorandum to critique communism. After participating in Prague Spring and being blacklisted after the invasion of Czechoslovakia, he became more politically active and helped found several dissident initiatives such as Charter 77 and the Committee for the Defense of the Unjustly Prosecuted. His political activities brought him under the surveillance of the secret police and he spent multiple stints in prison, the longest being nearly four years, between 1979 and 1983.

Havel's Civic Forum party played a major role in the Velvet Revolution that toppled communism in Czechoslovakia in 1989. He assumed the presidency shortly thereafter, and was reelected in a landslide the following year and after Slovak independence in 1993. Havel was instrumental in dismantling the Warsaw Pact and expanding NATO membership eastward. Many of his stances and policies, such as his opposition to Slovak independence, condemnation of the Czechoslovak treatment of Sudeten Germans after World War II, and granting of general amnesty to all those imprisoned under communism, were very controversial domestically. As such, he continually enjoyed greater popularity abroad than at home. Havel continued his life as a public intellectual after his presidency, launching several initiatives including the Prague Declaration on European Conscience and Communism,[2][3] the VIZE 97 Foundation, and the Forum 2000 annual conference.

Havel's political philosophy was one of anti-consumerism, humanitarianism, environmentalism, civil activism, and direct democracy.[1] He supported the Czech Green Party from 2004 until his death. He received numerous accolades during his lifetime including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Gandhi Peace Prize, the Philadelphia Liberty Medal, the Order of Canada, the Four Freedoms Award, the Ambassador of Conscience Award and the Hanno R. Ellenbogen Citizenship Award. The 2012–2013 academic year at the College of Europe was named in his honour.[4] He is considered by some to be one of the most important intellectuals of the 20th century.[5]

Biography

Early life

Havel was born in Prague on 5 October 1936[6] and grew up in a well-known, wealthy entrepreneurial and intellectual family, which was closely linked to the cultural and political events in Czechoslovakia from the 1920s to the 1940s.

His father, Václav Maria Havel, was the owner of the suburban Barrandov Terraces, located on the highest point of Prague, and of the large Barrandov Film Studios. Havel's mother, Božena Vavrečková,[7] came also from an influential family; her father was a Czechoslovak ambassador and a well-known journalist. In the early 1950s, the young Havel entered into a four-year apprenticeship as a chemical laboratory assistant and simultaneously took evening classes; he completed his secondary education in 1954. For political reasons, he was not accepted into any post-secondary school with a humanities program; therefore, he opted for studies at the Faculty of Economics of the Czech Technical University in Prague but dropped out after two years.[8] In 1964, Havel married Olga Šplíchalová.

Early theatre career

The intellectual tradition of his family was essential for Havel's lifetime adherence to the humanitarian values of the Czech culture.[9] After finishing his military service (1957–59), Havel had to bring his intellectual ambitions in line with the given circumstances, especially with the restrictions imposed on him as a descendant of former middle-class family. He found employment in Prague's theatre world as a stagehand at Prague's Theatre ABC – Divadlo ABC, and then at the Theatre On Balustrade – Divadlo Na zábradlí. Simultaneously, he was a student of dramatic arts by correspondence at the Theatre Faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (DAMU). His first own full-length play performed in public, besides various vaudeville collaborations, was The Garden Party (1963). Presented in a series of Theatre of the Absurd, at the Theatre on Balustrade, this play won him international acclaim. The play was soon followed by The Memorandum, one of his best known plays, and the The Increased Difficulty of Concentration, all at the Theatre on Balustrade. In 1968, The Memorandum was also brought to The Public Theater in New York, which helped to establish Havel's reputation in the United States. The Public Theater continued to produce his plays in the following years. After 1968, Havel's plays were banned from the theatre world in his own country, and he was unable to leave Czechoslovakia to see any foreign performances of his works.[10]

Dissident

During the first week of the invasion of Czechoslovakia, Havel assisted the resistance by providing an on-air narrative via Radio Free Czechoslovakia station (at Liberec). Following the suppression of the Prague Spring in 1968, he was banned from the theatre and became more politically active.[11] Short of money, he took a job in a brewery, an experience he wrote about in his play Audience. This play, along with two other "Vaněk" plays (so-called because of the recurring character Ferdinand Vaněk, a stand in for Havel), became distributed in samizdat form across Czechoslovakia, and greatly added to Havel's reputation of being a leading dissident (several other Czech writers later wrote their own plays featuring Vaněk).[12] This reputation was cemented with the publication of the Charter 77 manifesto, written partially in response to the imprisonment of members of the Czech psychedelic rock band The Plastic People of the Universe.[13] (Havel had attended their trial, which centered on the group's non-conformity in having long hair, using obscenities in their music, and their overall involvement in the Czech underground).[14] Havel co-founded the Committee for the Defense of the Unjustly Prosecuted in 1979. His political activities resulted in multiple stays in prison, and constant government surveillance and questioning by the secret police, (Státní bezpečnost). His longest stay in prison, from May 1979 to February 1983,[15] is documented in letters to his wife that were later published as Letters to Olga.

He was known for his essays, most particularly The Power of the Powerless, in which he described a societal paradigm in which citizens were forced to "live within a lie" under the communist regime.[16] In describing his role as a dissident, Havel wrote in 1979: "...we never decided to become dissidents. We have been transformed into them, without quite knowing how, sometimes we have ended up in prison without precisely knowing how. We simply went ahead and did certain things that we felt we ought to do, and that seemed to us decent to do, nothing more nor less."[17]

Presidency

On 29 December 1989, while he was leader of the Civic Forum, Havel became President of Czechoslovakia by a unanimous vote of the Federal Assembly. He had long insisted that he was not interested in politics and had argued that political change in the country should be induced through autonomous civic initiatives rather than through the official institutions. In 1990, soon after his election, Havel was awarded the Prize For Freedom of the Liberal International.[18][19][20]

In 1990, Czechoslovakia held its first free elections in 44 years, resulting in a sweeping victory for Civic Forum and its Slovak counterpart, Public Against Violence. Between them, they commanded strong majorities in both houses of the legislature. Havel retained his presidency. Despite increasing political tensions between the Czechs and the Slovaks in 1992, Havel supported the retention of the Czech and Slovak Federative Republic prior to the dissolution of the country. Havel sought reelection in 1992. Although no other candidate filed, when the vote came on 3 July, he failed to get a majority due to a lack of support from Slovak deputies. The largest Czech political party, the Civic Democratic Party, let it be known that it would not support any other candidate. After the Slovaks issued their Declaration of Independence, he resigned as President on 20 July, saying that he would not preside over the country's breakup.

However, when the Czech Republic was created as one of two successor states, he stood for election as its first president on 26 January 1993, and won. He did not have nearly the power that he had as president of Czechoslovakia. Although he was nominally the new country's chief executive, the Constitution of the Czech Republic intended to vest most of the real power in the prime minister. However, owing to his prestige, he still commanded a good deal of moral authority, and the presidency acquired a greater role than the framers intended. For instance, largely due to his influence, the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia, successor to the KSC's branch in the Czech Lands, was kept on the margins for most of his presidency, as Havel suspected it was still an unreformed Stalinist party.[21]

Havel's popularity abroad surpassed his popularity at home,[22] and he was often the object of controversy and criticism. During his time in office, Havel stated that the expulsion of the indigenous Sudeten German population after World War II was immoral, causing a great controversy at home. He also extended general amnesty as one of his first acts as President, in an attempt to lessen the pressure in overcrowded prisons as well as to release political prisoners and persons who may have been falsely imprisoned during the Communist era. Havel felt that many of the decisions of the previous regime's courts should not be trusted, and that most of those in prison had not received fair trials.[23] On the other hand, his critics claimed that this amnesty led to a significant increase in the crime rate. According to Havel's memoir To the Castle and Back, most of those who were released had less than a year to serve before their sentences ended. Statistics have not lent clear support to either claim.

In an interview with Karel Hvížďala (included in To the Castle and Back), Havel expressed his feeling that it was his most important accomplishment as President to have contributed to the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact. According to his statement the dissolution was very complicated. The infrastructure created by the Warsaw Pact was part of the economies of all member states, and the Pact's dissolution necessitated restructuring that took many years to complete. Furthermore, it took time to dismantle the Warsaw Pact's institutions; for example, it took two years for Soviet troops to fully withdraw from Czechoslovakia.

Following a legal dispute with his sister-in-law Dagmar Havlová (wife of his brother Ivan M. Havel), Havel decided to sell his 50% stake in the Lucerna Palace on Wenceslas Square in Prague, built from 1907 to 1921 by his grandfather, also named Václav Havel (spelled Vácslav,) one of the multifunctional "palaces" in the center of the once booming pre-World War I Prague. In a transaction arranged by Marián Čalfa, Havel sold the estate to Václav Junek, a former communist spy in France and leader of the soon-to-be-bankrupt conglomerate Chemapol Group, who later openly admitted that he bribed politicians of the Czech Social Democratic Party.[24]

In January 1996, Olga Havlová, his wife of 32 years, died of cancer at 62. In December 1996, Havel who had been a chain smoker for a long time, was diagnosed with lung cancer.[25] The disease reappeared two years later. He quit smoking. In 1997, he remarried, to actress Dagmar Veškrnová.[26]

Havel was among those influential politicians who contributed most to the transition of NATO from being an anti-Warsaw Pact alliance to its present form. Havel advocated vigorously for the inclusion of former-Warsaw Pact members, like the Czech Republic, into the Western alliance.[27][28]

Havel was re-elected president in 1998. He had to undergo a colostomy in Innsbruck when his colon ruptured while he was on holiday in Austria.[29] Havel left office after his second term as Czech president ended on 2 February 2003. Václav Klaus, one of his greatest political adversaries, was elected his successor as President on 28 February 2003. Margaret Thatcher wrote of the two men in her foreign policy treatise Statecraft, reserving the greater respect for Havel. Havel's dedication to democracy and his steadfast opposition to the Communist ideology earned him admiration.[30][31][32]

Post-presidential career

Beginning in 1997, Havel hosted Forum 2000, an annual conference to "identify the key issues facing civilisation and to explore ways to prevent the escalation of conflicts that have religion, culture or ethnicity as their primary components". In 2005, the former President occupied the Kluge Chair for Modern Culture at the John W. Kluge Center of the United States Library of Congress, where he continued his research on human rights.[33] In November and December 2006, Havel spent eight weeks as a visiting artist in residence at Columbia University. The stay was sponsored by the Columbia Arts Initiative and featured "performances, and panels centr[ing] on his life and ideas", including a public "conversation" with former U.S. President Bill Clinton. Concurrently, the Untitled Theater Company No. 61 launched a Havel Festival, the first complete festival of his plays in various venues throughout New York City, including The Brick Theater and the Ohio Theatre, in celebration of his 70th birthday.[25][34][35][36][37][38][39] Havel was a member of the World Future Society and addressed the Society's members on 4 July 1994. His speech was later printed in THE FUTURIST magazine (July 1995).[40]

Havel remained to be generally positive viewed from Czech citizens. In The Greatest Czech TV show (the Czech spin-off of the BBC 100 Greatest Britons show) in 2005, Havel received the third biggest amount of voices, so he was elected to be third greatest Czech when he was still alive.

Havel's memoir of his experience as President, To the Castle and Back, was published in May 2007. The book mixes an interview in the style of Disturbing the Peace with actual memoranda he sent to his staff with modern diary entries and recollections.[41]

On 4 August 2007, Havel met with members of the Belarus Free Theatre at his summer cottage in the Czech Republic in a show of his continuing support, which has been instrumental in the theatre's attaining international recognition and membership in the European Theatrical Convention.[42][43]

Havel's first new play in almost two decades, Leaving, was published in November 2007, and was to have had its world premiere in June 2008 at the Prague theater Divadlo na Vinohradech,[44] but the theater withdrew it in December as it felt it could not provide the technical support needed to mount the play.[45] The play instead premiered on 22 May 2008 at the Archa Theatre to standing ovations.[46] Havel based the play on King Lear, by William Shakespeare, and on The Cherry Orchard, by Anton Chekhov; "Chancellor Vilém Rieger is the central character of Leaving, who faces a crisis after being removed from political power."[44] The play had its English language premiere at the Orange Tree Theatre in London and its American premiere at The Wilma Theater in Philadelphia. Havel subsequently directed a film version of the play, which premiered in the Czech Republic on 22 March 2011.[47]

Other works included the short sketch Pět Tet, a modern sequel to Unveiling, and The Pig, or Václav Havel's Hunt for a Pig, which was premiered in Brno at Theatre Goose on a String and had its English language premiere at the 3LD Art & Technology Center in New York, in a production from Untitled Theater Company No. 61, in a production workshopped in the Ice Factory Festival in 2011[48][49] and later revived as a full production in 2014, becoming a New York Times Critic's Pick.[50]

In 2008, Havel became a Member of the European Council on Tolerance and Reconciliation. He met U.S. President Barack Obama in private before Obama's departure after the end of the European Union (EU) and United States (US) summit in Prague in April 2009.[51]

Havel was the chair of the Human Rights Foundation's International Council and a member of the international advisory council of the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation.[52]

.jpg)

From the 1980s Havel supported the green politics movement (partly due to his friendship with the co-founder of the German Die Grünen party Milan Horáček).[53][54]

From 2004 until his death he supported the Czech Green Party.[55][56][57][58]

Death

Havel died on the morning of 18 December 2011, aged 75, at his country home in Hrádeček.[59][60][61]

A week before his death, he met with his longtime friend, the Dalai Lama, in Prague;[62] Havel appeared in a wheelchair.[60] Prime Minister Petr Nečas announced a three-day mourning period from 21 to 23 December, the date announced by President Václav Klaus for the state funeral. The funeral Mass was held at Saint Vitus Cathedral, celebrated by the Archbishop of Prague Dominik Duka and Havel’s old friend Bishop Václav Malý. During the service, a 21 gun salute was fired in the former president’s honour, and as per the family’s request, a private ceremony followed at Prague's Strašnice Crematorium. Havel’s ashes were placed in the family tomb in the Vinohrady Cemetery in Prague.[63] On 23 December 2011 the Václav Havel Tribute Concert was held in Prague's Palác Lucerna.

Evaluations

Within hours Havel's death was met with numerous tributes, including from U.S. President Barack Obama, British Prime Minister David Cameron, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and former Polish President Lech Wałęsa. Merkel called Havel "a great European", while Wałęsa said he should have been given the Nobel Peace Prize.[60][64] In contrast, neither Russian President Dmitry Medvedev nor Prime Minister Vladimir Putin were mentioned by name in the Russian Embassy’s announcement, and no expression of condolences on the death of Havel was published on Medvedev’s official website.[65]

At news of his death former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, a native of Czechoslovakia, said, "He was one of the great figures of the 20th Century", while Czech expatriate novelist Milan Kundera said, "Václav Havel's most important work is his own life."[66] Communists took the opportunity to criticize Havel. Czech Communist Party leader Vojtěch Filip stated that Havel was a very controversial person and that his words often conflicted with his deeds. He criticized Havel for having supported NATO's war against the former Yugoslavia, repeating the charge that Havel had called the event a "humanitarian bombing",[67] even though Havel had expressly and emphatically denied ever having used such a phrase.[68]

An online petition organized by one of the best-known Czech and Slovak film directors, Fero Fenič, calling on the government and the Parliament to rename Prague Ruzyně Airport to Václav Havel International Airport attracted—in a week after 20 December 2011—support of over 80,000 Czech Republic and foreign signatories.[69] It was announced that the airport would be renamed the Václav Havel Airport Prague on 5 October 2012.[70][71]

Reviewing a new biography by Michael Zantovsky, Yale historian Marci Shore summarized his challenges as president:

- Havel’s message, “We are all responsible, we are all guilty,” was not popular. He enacted a general amnesty for all but the most serious criminals, apologized on behalf of Czechoslovakia for the post-World War II expulsion of the Sudeten Germans and resisted demands for a more draconian purge of secret police collaborators. These things were not popular either. And as the government undertook privatization and restitution, Havel confronted pyramid schemes, financial corruption and robber baron capitalism. He saw his country fall apart (if bloodlessly), becoming in 1993 the Czech Republic and Slovakia.[72]

Awards

In 1990, Havel received the Gottlieb Duttweiler Prize for his outstanding contributions to the well-being of the wider community. In the same year he received the Freedom medal.[73]

In 1993, he was elected an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.[74]

On 4 July 1994, Václav Havel was awarded the Philadelphia Liberty Medal. In his acceptance speech, he said: "The idea of human rights and freedoms must be an integral part of any meaningful world order. Yet I think it must be anchored in a different place, and in a different way, than has been the case so far. If it is to be more than just a slogan mocked by half the world, it cannot be expressed in the language of departing era, and it must not be mere froth floating on the subsiding waters of faith in a purely scientific relationship to the world."[75]

In 1997, Havel received the Prince of Asturias Award for Communication and Humanities and the Prix mondial Cino Del Duca.

In 2002, he was the third recipient of the Hanno R. Ellenbogen Citizenship Award presented by the Prague Society for International Cooperation. In 2003, he was awarded the International Gandhi Peace Prize by the government of India for his outstanding contribution towards world peace and upholding human rights in most difficult situations through Gandhian means; he was the inaugural recipient of Amnesty International's Ambassador of Conscience Award for his work in promoting human rights;[76] he received the US Presidential Medal of Freedom; and he was appointed as an honorary Companion of the Order of Canada.

In January 2008, the Europe-based A Different View cited Havel to be one of the 15 Champions of World Democracy.[77] In 2008 he was also awarded the Giuseppe Motta Medal for support for peace and democracy.[78] As a former Czech President, Havel was a member of the Club of Madrid.[79] In 2009 he was awarded the Quadriga Award,[80] but decided to return it in 2011 following the announcement of Vladimir Putin as one of the 2011 award recipients.[81]

Havel also received multiple honorary doctorates from various universities such as the prestigious Institut d'études politiques de Paris in 2009,[82] and was a member of the French Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques.

On 10 October 2011, Havel was awarded by the Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili with the St. George Victory Order.[83] In November 2014, he became only the fourth non-American honored with a bust in the U.S. Capitol.[84]

State awards

| Country | Awards[85] | Date | Place |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | Order of the Liberator San Martin Collar | 09/1996 | Buenos Aires |

| Austria | Decoration for Science and Art[86] | 11/2005 | Vienna |

| Brazil | Order of the Southern Cross Grand Collar Order of Rio Branco Grand Cross | 10/1990 09/1996 | Prague Brasília |

| Canada | Order of Canada Honorary Companion | 03/2004 | Prague |

| Czech Republic | Order of the White Lion 1st Class (Civil Division) with Collar Chain Order of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk 1st Class | 10/2003 | Prague |

| Estonia | Order of the Cross of Terra Mariana The Collar of the Cross | 04/1996 | Tallinn |

| France | Légion d'honneur Grand Cross Order of Arts and Letters Commander | 03/1990 02/2001 | Paris |

| Georgia | St. George's Order of Victory | 10/2011 | Prague |

| Germany | Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Special class of the Grand Cross | 05/2000 | Berlin |

| Hungary | Order of Merit of Hungary Grand Cross with Chain | 09/2001 | Prague |

| India | Gandhi Peace Prize | 08/2003 | Delhi |

| Italy | Order of Merit of the Italian Republic Grand Cross with Cordon | 04/2002 | Rome |

| Jordan | Order of al-Hussein bin Ali Collar | 09/1997 | Amman |

| Latvia | Order of the Three Stars Commander Grand Cross with Chain | 08/1999 | Prague |

| Lithuania | Order of Vytautas the Great Grand Cross | 09/1999 | Prague |

| Poland | Order of the White Eagle | 10/1993 | Warsaw |

| Portugal | Order of Liberty Grand Collar | 12/1990 | Lisbon |

| Republic of China (Taiwan) | Order of Brilliant Star with Special Grand Cordon | 11/2004 | Taipei |

| Slovakia | Order of the White Double Cross | 01/2003 | Bratislava |

| Slovenia | The Golden honorary Medal of Freedom | 11/1993 | Ljubljana |

| Spain | Order of Isabella the Catholic Grand Cross with Collar | 07/1995 | Prague |

| Turkey | Knight of Order of State of Republic of Turkey | 10/2000 | Ankara |

| Ukraine | Order of Yaroslav the Wise | 10/2006 | Prague |

| United Kingdom | Order of the Bath Knight Grand Cross (Civil Division) | 03/1996 | Prague |

| United States | Presidential Medal of Freedom | 07/2003 | Washington D.C. |

| Uruguay | Medal of the Republic | 09/1996 | Montevideo |

Václav Havel Prize for Creative Dissent

In April 2012, Havel's widow, Dagmar Havlová, authorized the creation of the Václav Havel Prize for Creative Dissent. The prize was created by the New York-based Human Rights Foundation and is awarded at the annual Oslo Freedom Forum. The prize "will celebrate those who engage in creative dissent, exhibiting courage and creativity to challenge injustice and live in truth."[87]

Works

Collections of poetry

- Čtyři rané básně (Four Early Poems)

- Záchvěvy I & II, 1954 (Quivers I & II)

- První úpisy, 1955 (First promissory notes)

- Prostory a časy, 1956 (Spaces and times)

- Na okraji jara (cyklus básní), 1956 (At the edge of spring (poetry cycle))

- Antikódy, 1964 (Anticodes)

Plays

- Life Ahead/You Have Your Whole Life Ahead of You, 1959, (Život před sebou) with Karel Brynda

- Motomorphosis/Motormorphosis, 1960/1961, (Motomorfóza), a sketch from Autostop

- Ela, Hela, and the Hitch, 1960/1961, (Ela, Hela a stop), a sketch for Autostop; discarded from the play, lost; found in 2009; published in 2011

- An Evening with the Family, 1960, (Rodinný večer)

- Hitchhiking, 1961, (Autostop), with Ivan Vyskočil

- The Best Years of Missis Hermanová, 1962, (Nejlepší rocky paní Hermanové) with Miloš Macourek

- The Garden Party (Zahradní slavnost), 1963

- The Memorandum (or The Memo), 1965, (Vyrozumění)

- The Increased Difficulty of Concentration, 1968, (Ztížená možnost soustředění)

- Butterfly on the Antenna, 1968, (Motýl na anténě)

- Guardian Angel, 1968, (Anděl strážný)

- Conspirators, 1971, (Spiklenci)

- The Beggar's Opera, 1975, (Žebrácká opera)

- Unveiling, 1975, (Vernisáž)- a Vanӗk play

- Audience, 1975, (Audience) – a Vanӗk play

- Mountain Hotel 1976, (Horský hotel)

- Protest, 1978, (Protest) – a Vanӗk play

- Mistake, 1983, (Chyba)

- Largo desolato 1984, (Largo desolato)

- Temptation, 1985, (Pokoušení)

- Redevelopment, 1987, (Asanace)

- The Pig, or Václav Havel's Hunt for a Pig (Prase, aneb Václav Havel's Hunt for a Pig), 1987; published in 2010; premiered in 2010, co-authored by Vladimír Morávek

- Tomorrow, 1988, (Zítra to spustíme)

- Leaving (Odcházení), 2007

- Dozens of Cousins (Pět Tet), 2010, a Vanӗk play, a short sketch/sequel to Unveiling

Non-fiction books

- The Power of the Powerless (1985) [Includes 1978 titular essay. Online

- Living in Truth (1986)

- Letters to Olga (Dopisy Olze) (1988)

- Disturbing the Peace (1991)

- Open Letters (1991)

- Summer Meditations (Letní přemítání) (1992/93)

- Towards a Civil Society (1994)

- The Art of the Impossible (1998)

- To the Castle and Back (2007)

Fiction books for children

- Pizh'duks

Films

- Odcházení, 2011

Cultural allusions and interests

- Havel was a major supporter of The Plastic People of the Universe, and close friend of its leader, Milan Hlavsa, its manager, Ivan Martin Jirous, and its guitarist/vocalist, Paul Wilson (who later became Havel's English translator and biographer) and a great fan of the rock band The Velvet Underground, sharing mutual respect with the principal singer-songwriter Lou Reed, and was also a lifelong Frank Zappa fan.[88][89]

- Havel was also a great supporter and fan of jazz and frequented such Prague clubs as Radost FX and the Reduta Jazz Club, where U.S. President Bill Clinton played the saxophone when Havel brought him there.[88]

- The period involving Havel's role in the Velvet Revolution and his ascendancy to the presidency is dramatized in part in the play Rock 'n' Roll, by Czechoslovakia-born English playwright Tom Stoppard. One of the characters in the play is called Ferdinand, in honor of Ferdinand Vaněk, the protagonist of three of Havel's plays and a Havel stand-in.

- In 1996, due to his contributions to the arts, he was honorably mentioned in the rock opera Rent during the song "La Vie Boheme", though his name was mispronounced on the original soundtrack.

- Samuel Beckett's 1982 short play, Catastrophe, was dedicated to Havel while he was held as a political prisoner in Czechoslovakia.[90]

- In David Weber's Honor Harrington series, a genetic slave turned freedom fighter (and later Prime Minister of a planet of freed slaves) names himself "W.E.B. du Havel" in honor of his two favorite writers on the subject of freedom, W. E. B. du Bois and Havel.

The Václav Havel Library

The Václav Havel Library, located in Prague, is a charitable organization founded by Dagmar Havlová, Karel Schwarzenberg and Miloslav Petrusek on 26 July 2004. It maintains a collection of pictorial, audio and written materials and other artefacts linked to Václav Havel.[91][92] The institution gathers these materials for the purpose of digitisation, documentation and research and to promote his ideas. It organises lectures,[93] holds conferences and social and cultural events that introduce the public to the work of Václav Havel and club discussion meetings on current social issues. It runs educational activities for second-level students. It is also involved in the issuing of publications.

The library makes accessible Václav Havel’s literary, philosophical and political writings, and provides a digital reading room for researchers and students in the Czech Republic and elsewhere.

the Václav Havel Library also organises seminars, readings, exhibitions, concerts and theatre performances at Galerie Montmartre in Prague’s Old Town, where there is a permanent exhibition “Václav Havel: Czech Myth, or Havel in a Nutshell”.

In May 2012, the Library opened a branch New York City, USA, named the Vaclav Havel Library Foundation. In 2013 the main library moved to larger premises at U Drahomířina sloupu on Loretánské náměstí in the Prague Castle complex, with architectural renovations designed by Ricardo Bofill.[94]

See also

- Barrandov Terraces

- Charter 77

- Civil resistance

- Hrad (politics)

- Humanitarian bombing, a term claimed to have been coined by Havel

- List of peace activists

- Nonviolent resistance

- Seoul Peace Prize

- Velvet Revolution

- Havel's Place

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Crain, Caleb (21 March 2012). "Havel's Specter: On Václav Havel". The Nation. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ↑ Tismăneanu, Vladimir (2010). "Citizenship Restored". Journal of Democracy 21 (1): 128–135. doi:10.1353/jod.0.0139.

- ↑ "Prague Declaration on European Conscience and Communism - Press Release". Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation. 9 June 2008. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- ↑ "Opening Ceremony, Bruges Campus". Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ↑ "Prospect Intellectuals: The 2005 List". Prospect. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ↑ Webb, W. L. (18 December 2011). "Václav Havel obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ "Havel, Vaclav, Contemporary Authors, New Revision Series". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ "::.Václav Havel.::The official website of Václav Havel, writer, dramatist, dissident, prisoner of conscience, human rights activist, former president of Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic". Vaclavhavel.cz. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ "Václav Havel - Prague Castle". Hrad.cz. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ "Václav Havel". Telegraph. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ Havel, V. (1975). "Letter to Dr. Husak"

- ↑ Goetz-Stankiewicz, Marketa. The Vanӗk Plays, 1987, University of British Columbia Press

- ↑ Richie Unterberger, "The Plastic People of the Universe", richieunterberger.com 26 February 2007. Retrieved 29 April 2007.

- ↑ Eda Kriseová (1993). Václav Havel: The Authorized Biography. St. Martins Press. pp. 98–99. ISBN 0-88687-739-3.

- ↑ Eda Kriseová (1993). Václav Havel: The Authorized Biography. St. Martins Press. pp. 168, 195. ISBN 0-88687-739-3.

- ↑ Václav Havel, The Power of the Powerless, in: Václav Havel, et al The power of the powerless. Citizen against the state in central-eastern Europe, Abingdon, 2010 pp. 10–60 ISBN 978-0-87332-761-9

- ↑ Keane, John (2000). Václav Havel: A Political Tragedy in Six Acts. Basic Books. p. 264. ISBN 0-465-03719-4.

- ↑ "Václav Havel (1990)". Liberal-international.org. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ↑ Stanger, Richard L. "Václav Havel: Heir to a Spiritual Legacy". The Christian Century (Christian Century Foundation), 11 April 1990: pp. 368–70. Rpt. in religion-online.org ("with permission"; "prepared for Religion Online by Ted & Winnie Brock"). ["Richard L. Stanger is senior minister at Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims in Brooklyn, New York".]

- ↑ Tucker, Scott. "Capitalism with a Human Face?". The Humanist (American Humanist Association), 1 May 1994, "Our Queer World". Rpt. in High Beam Encyclopedia (an online encyclopedia). Retrieved 21 December 2007. ["Václav Havel's philosophy and musings."]

- ↑ Thompson, Wayne C. (2008). The World Today Series: Nordic, Central and Southeastern Europe 2008. Harpers Ferry, West Virginia: Stryker-Post Publications. ISBN 978-1-887985-95-6.

- ↑ Ponikelska, Lenka. "Czech Cabinet Meets to Plan Havel’s Funeral as EU Holds Minute of Silence". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ "Havel's New Year's address". Old.hrad.cz. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ↑ Paul Berman, "The Poet of Democracy and His Burdens", The New York Times Magazine 11 May 1997 (original inc. cover photo), as rpt. in English translation at Newyorske listy (New York Herald). Retrieved 29 April 2007.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "VACLAV HAVEL - Radio Prague". Radio.cz. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ Richard Allen Greene "Václav Havel: End of an era", BBC News, 9 October 2003

- ↑ Václav Havel, "NATO: The Safeguard of Stability and Peace In the Euro-Atlantic Region", in European Security: Beginning a New Century, eds. General George A. Joulwan & Roger Weissinger-Baylon, papers from the XIIIth NATO Workshop: On Political-Military Decision Making, Warsaw, Poland, 19–23 June 1996.

- ↑ Žižek, Slavoj (28 October 1999). "Attempts to Escape the Logic of Capitalism. Book review of Václav Havel: A Political Tragedy in Six Acts, by John Keane". London Review of Books. Archived from the original on 15 April 2009. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- ↑ Havel's Medical Condition Seems to Worsen, The New York Times. 5 August 1998.

- ↑ Welch, Matt. "Velvet President", Reason (May 2003). Rpt. in Reason Online. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- ↑ Václav Havel "Famous Czechs of the Past Century: Václav Havel" – English version of article featured on the official website of the Czech Republic.

- ↑ "Václav Havel". Prague Life. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ "Václav Havel: The Emperor Has No Clothes Webcast (Library of Congress)". Loc.gov. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ Havel at Columbia; "Celebrating the Life and Art of Václav Havel: New York City, October through December 2006".

- ↑ Capps, Walter H. "Interpreting Václav Havel". Cross Currents (Association for Religion & Intellectual Life) 47.3 (Fall 1997). Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- ↑ Havel at Columbia: Václav Havel: The Artist, The Citizen, The Residency, a multi-media website developed for Havel's seven-week residency at Columbia University, in Fall 2006; features biographies, timelines, interviews, profile and bibliographies (see "References" above).

- ↑ "Honours: Order of Canada: Václav Havel". Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- ↑ "The Havel Festival : Václav Havel". Untitledtheater.com. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ "The Havel Festival". Untitledtheater.com. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ "Václav Havel on Transcendence | World Future Society". Wfs.org. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ Pinder, Ian (16 August 2008). "Czechout". The Guardian (UK). Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ↑ "Belarus Free Theatre Meet Václav Havel", press release, Belarus Free Theatre, 13 August 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- ↑ Michael Batiukov, "Belarus 'Free Theatre' is Under Attack by Militia in Minsk, Belarus", American Chronicle, 22 August 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Adam Hetrick, "Václav Havel's Leaving May Arrive in American Theatres", Playbill, 19 November 2007. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- ↑ Daniela Lazarová, "Will It Be Third Time Lucky for Václav Havel's 'Leaving'?", Radio Prague, 14 December 2007. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- ↑ "Everyone loves Havel's Leaving". Archived from the original on 30 May 2008. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ↑ Feifer, Gregory (23 March 2011). "Havel Film Premieres In Prague". Rferl.org. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ↑ "DIVADLO.CZ: Of Pigs and Dissidents". Host.theatre.cz. 29 June 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ↑ Callahan, Dan. "Summer Preview: Performance | Theater Reviews | The L Magazine – New York City's Local Event and Arts & Culture Guide". The L Magazine. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ↑ "NEW YORK TIMES: A Song-And-Dance Survival Strategy". nytimes.com. 12 March 2014.

- ↑ "Havel's gift for Obama to be displayed in Prague gallery | Prague Monitor". Archived from the original on 11 April 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ↑ "International Advisory Council". Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ↑ "Václav Havel byl součástí odvěkého lidského snažení o lepší svět - Deník Referendum". Denikreferendum.cz. 2011-12-19. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ "Český rozhlas Plus (archiv - Portréty)". Prehravac.rozhlas.cz. 2011-12-18. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ "Zelené podpořil Havel, vymezují se proti TOP 09 –". Novinky.cz. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ "Zelení představili své sympatizanty - Havla, Schwarzenberga a Holubovou –". Novinky.cz. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ "Havel podpořil zelené. Srovnal továrny s koncentráky - tn.cz". Tn.nova.cz. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ "Aktuální zpravodajství | Václav Havel vyzývá občany k volbě Strany zelených | Tiscali.cz". Zpravy.tiscali.cz. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ Dan Bilefsky; Jane Perlez (18 December 2011). "Václav Havel, Former Czech President, Dies at 75". The New York Times.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 "Václav Havel, Czech statesman and playwright, dies at 75". BBC. 18 December 2011.

- ↑ Paul Wilson (9 February 2012). "Václav Havel (1936–2011)". The New York Review of Books 59 (2). Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- ↑ "Dalai Lama pays 'friendly' visit to Prague". The Prague Post. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ "Václav Havel to be given state funeral and highest military honors". Radio Praha. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ↑ "World Reacts To Václav Havel's Death". Radio Free Europe. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ "No Medvedev or Putin at Havel’s funeral? No Temelín contract for Russians!". Czechposition.com. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ↑ A continent mourns Václav Havel "World Reacts To Václav Havel's Death". Radio Free Europe. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ "Czech politicians express sorrow over Václav Havel's death" Prague Daily Monitor, 19 December 2011

- ↑ Václav Havel, K Falbrově lži, Mladá fronta DNES 24 May 2004: Obskurní pojem "humanitární bombardování" jsem samozřejmě nejen nevymyslel, ale nikdy ani nepoužil a použít nemohl, neboť mám – troufám si tvrdit – vkus.

- ↑ "Petition to name the Prague - Ruzyne airport Václav Havel International Airport". Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ↑ "Radio Prague - Government renames airport after Havel, but botches translation". Radio.cz. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ "Letiště Václava Havla". Vaclavhavelairport.com. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ Marci Shore, "'‘Havel: A Life,’ by Michael Zantovsky," New York Times Sunday Book Review (Dec 27, 2014)

- ↑ Four Freedoms Award#Freedom Medal

- ↑ "Royal Society of Literature All Fellows". Royal Society of Literature. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ↑ 1994 Speech Václav Havel – Liberty Medal, National Constitution Center

- ↑ Shipsey, Bill. "Václav Havel: Ambassador of Conscience 2003: From Prisoner to President – A Tribute". Amnesty International (October 2003). Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- ↑ A Different View, Issue 19, January 2008.

- ↑

- ↑ "The Club of Madrid". Clubmadrid.org. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ↑ "Havel receives Quadriga prestigious German award". Prague Daily Monitor (original source: Czech Press Agency. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

- ↑ "German Group Cancels Prize to Putin After Outcry", The New York Times, 16 July 2011.

- ↑ "Honorary Doctorates". Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- ↑ ვაცლავ ჰაველის დაჯილდოება on YouTube

- ↑ Gershman, Carl (16 November 2014). "Are Czechs giving up on moral responsibility?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ↑ "State Decorations". Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ↑ "Reply to a parliamentary question" (PDF) (in German). p. 1711. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ↑ "The Václav Havel Prize for Creative Dissent". Human Rights Foundation. 11 April 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 Biographies and bibliographies, "Havel at Columbia: Bibliography: Human Rights Archive". Retrieved 29 April 2007.

- ↑ Sam Beckwith, "Václav Havel & Lou Reed", Prague.tv 24 January 2005, updated 27 January 2005. Retrieved 26 April 2007.

- ↑ 'Catastrophe', Collected Shorter Plays of Samuel Beckett (New York: Grove P, 1994) pp. 295–302 ISBN 0-8021-5055-1.

- ↑ Miloslav Rechcígl (2008). On Behalf of Their Homeland: Fifty Years of SVU : an Eyewitness Account of the History of the Czechoslovak Society of Arts and Sciences (SVU). East European Monographs. ISBN 978-0-88033-630-7.

- ↑ "Havel’s Letter to Husák: still an inspiration 40 years on". Radio Prague, November 4 2015 | Azadeh Mohammadi, David Vaughan

- ↑ "Taiwanese disappointed at Zeman's view of Taiwan". Prague Daily Monitor 24 March 2015

- ↑ "New venue doubles capacity for Václav Havel Library events". Radio Prague, January 10 2014 | Ian Willoughby

Primary sources

- Works by Václav Havel

- Commentaries and Op-eds by Václav Havel and in conjunction between Václav Havel and other renowned world leaders for Project Syndicate.

- "Excerpts from The Power of the Powerless (1978)", by Václav Havel. "Excerpts from the Original Electronic Text provided by Bob Moeller, of the University of California, Irvine."

- "The Need for Transcendence in the Postmodern World" (Speech republished in THE FUTURIST magazine). Retrieved 19 December 2011

- Václav Havel: 'We are at the beginning of momentous changes' at the Wayback Machine (archived June 22, 2008). Czech.cz (Official website of the Czech Republic), 10 September 2007. Retrieved 21 December 2007. On personal responsibility, freedom and ecological problems.

- Two Messages Václav Havel on the Kundera affair, English, salon.eu.sk, October 2008

- Media interviews with Václav Havel

- After the Velvet, an Existential Revolution? dialogue between Václav Havel and Adam Michnik, English, salon.eu.sk, November 2008

- Warner, Margaret. "Online Focus: Newsmaker: Václav Havel". The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer. PBS, broadcast 16 May 1997. Retrieved 21 December 2007. (NewsHour transcript.)

Biographies

- Keane, John. Václav Havel: A Political Tragedy in Six Acts. New York: Basic Books, 2000. ISBN 0-465-03719-4. (A sample chapter [in HTML and PDF formats] is linked on the author's website, "Books".)

- Kriseová, Eda. Václav Havel. Trans. Caleb Crain. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1993. ISBN 0-312-10317-4.

- Pontuso, James F. Václav Havel: Civic Responsibility in the Postmodern Age. New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004. ISBN 0-7425-2256-3.

- Rocamora, Carol. Acts of Courage. New York: Smith & Kraus, 2004. ISBN 1-57525-344-5.

- Symynkywicz, Jeffrey. Václav Havel and the Velvet Revolution. Parsippany, New Jersey: Dillon Press, 1995. ISBN 0-87518-607-6.

- Zantovsky, Michael. Havel: A Life (2014)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Václav Havel |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Václav Havel. |

- Václav Havel Official website

- Václav Havel Library, Prague

- Encyclopaedia Britannica's biography of Václav Havel

- Watch Citizen Havel, a film about Václav Havel, at www.dafilms.com

- Works by or about Václav Havel in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Václav Havel at the Internet Movie Database

- Václav Havel collected news and commentary at The Guardian

- Václav Havel collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- Václav Havel archive from The New York Review of Books

- Havel at Columbia: Bibliography: Human Rights Archive

- Radio Prague's detailed account of Havel's life

- Bio of Václav Havel

- New York Times obit

- The Havel Festival

- The Dagmar and Václav Havel Foundation

- The Velvet Revolution Freedom Collection interview

- Last interview, given to The European Strategist

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Marián Čalfa Acting |

President of Czechoslovakia 1989–1992 |

Office abolished |

| New office | President of the Czech Republic 1993–2003 |

Succeeded by Václav Klaus |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|