Uyghur language

| Uyghur | |

|---|---|

| ئۇيغۇرچە / ئۇيغۇر تىلى | |

|

Uyghur written in Perso-Arabic script | |

| Pronunciation | [ʊjʁʊrˈtʃɛ], [ʊjˈʁʊr tili] |

| Native to | Xinjiang of China , Kazakhstan |

| Ethnicity | Uyghur |

Native speakers | 10.4 million (2010)[1] |

Early forms |

Karakhanid

|

| Arabic (Uyghur alphabet) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | China (Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region) |

| Regulated by | Working Committee of Ethnic Language and Writing of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

ug |

| ISO 639-2 |

uig |

| ISO 639-3 |

uig |

| Glottolog |

uigh1240[2] |

|

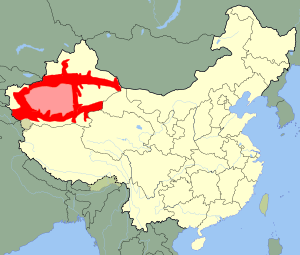

Geographical extent of Uyghur in China | |

Uyghur or Uighur /ˈwiːɡər/[3][4] (ئۇيغۇر تىلى Uyghur tili, ئۇيغۇرچە Uyghurche),[5][6] formerly known as Eastern Turki, is a Turkic language with 8 to 11 million speakers, spoken primarily by the Uyghur people in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of Western China. Significant communities of Uyghur-speakers are located in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, and various other countries have Uyghur-speaking expatriate communities. Uyghur is an official language of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, and is widely used in both social and official spheres, as well as in print, radio, and television, and is used as a lingua franca by other ethnic minorities in Xinjiang.

Uyghur belongs to the Karluk branch of the Turkic language family, which also includes languages such as Uzbek. Like many other Turkic languages, Uyghur displays vowel harmony and agglutination, lacks noun classes or grammatical gender, and is a left-branching language with subject–object–verb word order. More distinctly Uyghur processes include, especially in northern dialects, vowel reduction and umlauting. In addition to influence of other Turkic languages, Uyghur has historically been influenced strongly by Persian and Arabic, and more recently by Mandarin Chinese and Russian.

The Arabic-derived writing system is the most common and the only standard in China, although other writing systems are used for auxiliary and historical purposes. Unlike most Arabic-derived scripts, the Uyghur Arabic alphabet has mandatory marking of all vowels. Two Latin and one Cyrillic alphabet are also used, though to a much lesser extent. The Arabic and Latin alphabets both have 32 characters.

History

The Middle Turkic languages are the direct ancestor of the Karluk languages, including Uyghur and the Uzbek language.

Modern Uyghur is not descended from Old Uyghur, rather, it is a descendant of the Karluk language spoken by the Kara-Khanid Khanate.[7] Western Yugur is considered to be the true descendant of Old Uyghur, and is also called "Neo-Uyghur". Modern Uyghur is not a descendant of Old Uyghur, but is descended from the Xākānī language described by Mahmud al-Kashgari in Dīwānu l-Luġat al-Turk.[8] Modern Uyghur and Western Yugur belong to entirely different branches of the Turkic language family, respectively the southeastern Turkic languages and the northeastern Turkic languages.[9][10] The Western Yugur language, although in geographic proximity, is more closely related to the Siberian Turkic languages in Siberia.[11]

Probably around 1077,[12] a scholar of the Turkic languages, Mahmud al-Kashgari from Kashgar in modern-day Xinjiang, published a Turkic language dictionary and description of the geographic distribution of many Turkic languages, Dīwān ul-Lughat al-Turk (English: Compendium of the Turkic Dialects; Uyghur: تۈركى تىللار دىۋانى Türki Tillar Diwani). The book, described by scholars as an "extraordinary work,"[13][14] documents the rich literary tradition of Turkic languages; it contains folk tales (including descriptions of the functions of shamans[14]) and didactic poetry (propounding "moral standards and good behaviour"), besides poems and poetry cycles on topics such as hunting and love,[15] and numerous other language materials.[16]

Middle Turkic languages, through the influence of Perso-Arabic after the 13th century, developed into the Chagatai language, a literary language used all across Central Asia until the early 20th century. After Chaghatai fell into extinction, the standard versions of Uyghur and Uzbek were developed from dialects in the Chagatai-speaking region, showing abundant Chaghatai influence. Uyghur language today shows considerable Persian influence as a result from Chagatai, including numerous Persian loanwords.[17]

The historical term "Uyghur" was appropriated for the language formerly known as Eastern Turki by government officials in the Soviet Union in 1922 and in Xinjiang in 1934.[18][19] Sergey Malov was behind the idea of renaming Turki to Uyghurs.[20]

Classification

The Uyghur language belongs to the Karlik Turkic (or Karluk or Qarluq) branch of the Turkic language family. It is closely related to Äynu, Lop, Ili Turki, the extinct language Chagatay (the East Karluk languages), and more distantly to Uzbek (which is West Karluk).

Early linguistic scholarly studies of Uyghur include Julius Klaproth's 1812 Dissertation on language and script of the Uighurs (Abhandlung über die Sprache und Schrift der Uiguren) which was disputed by Isaak Jakob Schmidt. In this period, Klaproth correctly asserted that Uyghur was a Turkic language, while Schmidt believed that Uyghur should be classified with Tangut languages.[21]

Dialects

It is widely accepted that Uyghur has three main dialects, all based on their geographical distribution. Each of these main dialects have a number of sub-dialects which all are mutually intelligible to some extent.

- Central: Spoken in an area stretching from Kumul towards south to Yarkand

- Southern: Spoken in an area stretching from Guma towards east to Charqaliq

- Eastern: Spoken in an area stretching from Charqaliq towards north to Chongköl

The Central dialects are spoken by 90% of the Uyghur-speaking population, while the two other branches of dialects only are spoken by a relatively small minority.[22]

Vowel reduction is common in the northern parts of where Uyghur is spoken, but not in the south.[23]

Status

Uyghur is spoken by about 8-11 million people in total.[24][25][26] In addition to being spoken primarily in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of Western China, mainly by the Uyghur people, Uyghur was also spoken by some 300,000 people in Kazakhstan in 1993, some 90,000 in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan in 1998, 3,000 in Afghanistan and 1,000 in Mongolia, both in 1982.[24] Smaller communities also exist in Albania, Australia, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Indonesia, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sweden, Taiwan, Tajikistan, Turkey, United Kingdom and the United States (New York City).[25]

The Uyghurs are one of the 56 recognized ethnic groups in China, and Uyghur is an official language of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, along with Standard Chinese. As a result, Uyghur can be heard in most social domains in Xinjiang, and also in schools, government and courts.[24] Of the other ethnic minorities in Xinjiang, those populous enough to have their own autonomous prefectures, such as the Kazakhs and the Kyrgyz, have access to schools and government services in their native language. Smaller minorities, however, do not have a choice and must attend Uyghur-medium schools.[27] These include the Xibe, Tajiks, Daurs, and Russians.[28]

About 80 newspapers and magazines are available in Uyghur; five TV channels and ten publishers serve as the Uyghur media. Outside of China, Radio Free Asia and TRT provide news in Uyghur.

Phonology

Vowels

The vowels of the Uyghur language are, in their alphabetical order (in Uyghur Latin script), ⟨a⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨ë ⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨ö⟩, ⟨u⟩, ⟨ü⟩. There are no diphthongs in Uyghur and when two vowels come together, which occurs in some loanwords, each vowel retains its individual sound. And disregarding vowel length distinction in current Uyghur orthographies.

The Uyghur vowel system is characterised by the oppositions front vs. back, high vs. low and unrounded vs. rounded.

The Uyghur vowel system may be subcategorized on the basis of height, backness and roundness. It has been argued, within a lexical phonology framework, that /e/ has a back counterpart /ɤ/. And modern Uyghur lacks a clear differentiation i:ɯ

| Front / Aldi (Qëlin) | Back / Arqa (Inchike) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded / Lewleshmigen (Tüz) | Rounded / Lewleshken (Yumulaq) | Unrounded / Lewleshmigen (Tüz) | Rounded / Lewleshken (Yumulaq) | |

| High / Igiz(Tar) | ɪ, i | y, ʏ | (ɨ), (ɯ) | ʊ, u |

| Mid / Ara(Ottura) | e | (ɤ) | ||

| Low / Pes(Keng) | ɛ, æ | ø | ʌ, ɑ | o, ɔ |

Uyghur vowels are by default short, but some phonologists have argued that long vowels also exist because of historical vowel assimilation (above) and through loanwords. Underlyingly long vowels would resist vowel reduction and devoicing, introduce non-final stress, and be analyzed as |Vj| or |Vr| before a few suffixes. However, the conditions in which they are actually pronounced as distinct from their short counterparts have not been fully researched.[29]

The high vowels undergo some tensing when they occur adjacent to alveolars (s, z, r, l), palatals (j), dentals (t̪, d̪, n̪), and post-alveolar affricates (t͡ʃ, d͡ʒ), e.g. chiraq [ʧʰˈiraq] ‘lamp’, jenubiy [ʤɛnʊˈbi:] ‘southern’, yüz [jyz] ‘face; hundred’, suda [su:ˈda] ‘in/at (the) water’.

Both [ɪ] and [ɯ] undergo apicalisation after alveodental continuants in unstressed syllables, e.g. siler [sɪ̯læː(r)] ‘you (plural)’, ziyan [zɪ̯ˈjɑːn] ‘harm’. They are medialised after /χ/ or before /l/, e.g. til [tʰɨl] ‘tongue’, xizmet [χɨzˈmɛt] ‘work;job;service’. After velars, uvulars and /f/ they are realised as [e], e.g. giram [ɡeˈrʌm] ‘gramme’, xelqi [χɛlˈqʰe] ‘his [etc.] nation’, Finn [fen] ‘Finn’. Between two syllables that contain a rounded back vowel each, they are realised as back, e.g. qolimu [qʰɔˈlɯmʊ] ‘also his [etc.] arm’.

Any vowel undergoes laxing and backing when it occurs in uvular(/q/, /ʁ/, /χ/) and laryngeal(Glottal)(/ɦ/, /ʔ/) environments, e.g. qiz [qʰɤz] ‘girl’, qëtiq [qʰɤˈtɯq] ‘yogurt’, qeghez [qʰæˈʁæz] ‘paper’, qum [qʰʊm] ‘sand’, qolay [qʰɔˈlʌɪ] ‘convenient’, qan [qʰɑn] ‘blood’, ëghiz [ʔeˈʁez] ‘mouth’, hisab [ɦɤˈsʌp] ‘number’, hës [ɦɤs] ‘hunch’, hemrah [ɦæmˈrʌh] ‘partner’, höl [ɦœɫ] ‘wet’, hujum [ɦuˈʤʊm] ‘assault’, halqa [ɦɑlˈqʰɑ] ‘ring’.

Lowering tends to apply to the non-high vowels when a syllable-final liquid assimilates to them, e.g. kör [cʰøː] ‘look!’, boldi [bɔlˈdɪ] ‘he [etc.] became’, ders [dae:s] ‘lesson’, tar [tʰɑː(r)] ‘narrow’.

Official Uyghur orthographies do not mark vowel length, and also do not distinguish between /ɪ/ (e.g., بىلىم /bɪlɪm/ 'knowledge') and back /ɯ/ (e.g., تىلىم /tɯlɯm/ 'my language'); these two sounds are in complementary distribution, but phonological analyses claim that they play a role in vowel harmony and are separate phonemes.[30] /e/ only occurs in words of non-Turkic origin and as the result of vowel raising.[31]

Uyghur has systematic vowel reduction (or vowel raising) as well as vowel harmony. Words usually agree in vowel backness, but compounds, loans, and some other exceptions often break vowel harmony. Suffixes surface with the rightmost [back] value in the stem, and /e, ɪ/ are transparent (as they don't contrast for backness). Uyghur also has rounding harmony.[32]

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Post- alveolar |

Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n̪ | ŋ | |||||||||

| Stop | p | b | t̪ | d̪ | tʃ | dʒ | k | g | q | ʔ | ||

| Fricative | f | (v) | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | χ | ʁ | h | |||

| Trill | r | |||||||||||

| Approximant | l | j | w | |||||||||

Uyghur voiceless stops are aspirated word-initially and intervocalically.[33] The pairs /p, b/, /t, d/, /k, ɡ/, and /q, ʁ/ alternate, with the voiced member devoicing in syllable-final position, except in word-initial syllables. This devoicing process is usually reflected in the official orthography, but an exception has been recently made for certain Perso-Arabic loans.[34] Voiceless phonemes do not become voiced in standard Uyghur.[35]

Suffixes display a slightly different type of consonant alternation. The phonemes /ɡ/ and /ʁ/ anywhere in a suffix alternate as governed by vowel harmony, where /ɡ/ occurs with front vowels and /ʁ/ with back ones. Devoicing of a suffix-initial consonant can occur only in the cases of /d/ → [t], /ɡ/ → [k], and /ʁ/ → [q], when the preceding consonant is voiceless. Lastly, the rule that /g/ must occur with front vowels and /ʁ/ with back vowels can be broken when either [k] or [q] in suffix-initial position becomes assimilated by the other due to the preceding consonant being such.[36]

Loan phonemes have influenced Uyghur to various degrees. /d͡ʒ/ and /χ/ were borrowed from Arabic and have been nativized, while /ʒ/ from Persian less so. /f/ only exists in very recent Russian and Chinese loans, since Perso-Arabic (and older Russian and Chinese) /f/ became Uyghur /p/. Perso-Arabic loans have also made the contrast between /k, ɡ/ and /q, ʁ/ phonemic, as they occur as allophones in native words, the former set near front vowels and the latter near a back vowels. Some speakers of Uyghur distinguish /v/ from /w/ in Russian loans, but this is not represented in most orthographies. Other phonemes occur natively only in limited contexts, i.e. /h/ only in few interjections, /d/, /ɡ/, and /ʁ/ rarely initially, and /z/ only morpheme-final. Therefore, the pairs */t͡ʃ, d͡ʒ/, */ʃ, ʒ/, and */s, z/ do not alternate.[37][38]

Phonotactics

The primary syllable structure of Uyghur is CV(C)(C).[25] Uyghur syllable structure is usually CV or CVC, but CVCC can also occur in some words. When syllable-coda clusters occur, CC tends to become CVC in some speakers especially if the first consonant is not a sonorant. In Uyghur, any consonant phoneme can occur as the syllable onset or coda, except for /ʔ/ which only occurs in the onset and /ŋ/, which never occurs word-initially. In general, Uyghur phonology tends to simplify phonemic consonant clusters by means of elision and epenthesis.[39]

Orthography

Since the beginning of the literary tradition of Uyghur in the 5th century , it has been written in numerous different writing systems and continues to be. Unlike many other modern Turkic languages, Uyghur is primarily written using an Arabic alphabet, although a Cyrillic alphabet and two Latin alphabets also are in use to a much lesser extent. Unusually for an alphabet based on the Persian, full transcription of vowels is indicated. (Among the Arabic family of alphabets, only a few, such as Kurdish, distinguish all vowels.)

The four alphabets in use today can be seen below.

- Uyghur Arabic alphabet or UEY

- Uyghur Cyrillic alphabet or USY

- The Uyghur New Script or UYY

- Uyghur Latin alphabet or ULY

In the table below the alphabets are shown side-by-side for comparison, together with a phonetic transcription in the International Phonetic Alphabet.

| # | IPA | UEY | USY | UYY | ULY | # | IPA | UEY | USY | UYY | ULY | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | /ɑ/ | ئا | А а | A a | A a | 17 | /q/ | ق | Қ қ | Ⱪ ⱪ | Q q | |

| 2 | /ɛ/ ~ /æ/ | ئە | Ә ә | Ə ə | E e | 18 | /k/ | ك | К к | K k | K k | |

| 3 | /b/ | ب | Б б | B b | B b | 19 | /ɡ/ | گ | Г г | G g | G g | |

| 4 | /p/ | پ | П п | P p | P p | 20 | /ŋ/ | ڭ | Ң ң | Ng ng | Ng ng | |

| 5 | /t/ | ت | Т т | T t | T t | 21 | /l/ | ل | Л л | L l | L l | |

| 6 | /dʒ/ | ج | Җ җ | J j | J j | 22 | /m/ | م | М м | M m | M m | |

| 7 | /tʃ/ | چ | Ч ч | Q q | Ch ch | 23 | /n/ | ن | Н н | N n | N n | |

| 8 | /χ/ | خ | Х х | H h | X x | 24 | /h/ | ھ | Һ һ | Ⱨ ⱨ | H h | |

| 9 | /d/ | د | Д д | D d | D d | 25 | /o/ | ئو | О о | O o | O o | |

| 10 | /r/ | ر | Р р | R r | R r | 26 | /u/ | ئۇ | У у | U u | U u | |

| 11 | /z/ | ز | З з | Z z | Z z | 27 | /ø/ | ئۆ | Ө ө | Ɵ ɵ | Ö ö | |

| 12 | /ʒ/ | ژ | Ж ж | Ⱬ ⱬ | Zh zh | 28 | /y/ | ئۈ | Ү ү | Ü ü | Ü ü | |

| 13 | /s/ | س | С с | S s | S s | 29 | /v/~/w/ | ۋ | В в | V v | W w | |

| 14 | /ʃ/ | ش | Ш ш | X x | Sh sh | 30 | /e/ | ئې | Е е | E e | Ë ë | |

| 15 | /ʁ/ | غ | Ғ ғ | Ƣ ƣ | Gh gh | 31 | /ɪ/ ~ /i/ | ئى | И и | I i | I i | |

| 16 | /f/ | ف | Ф ф | F f | F f | 32 | /j/ | ي | Й й | Y y | Y y |

Grammar

Uyghur is an agglutinative language with a subject–object–verb word order. Nouns are inflected for number and case, but not gender and definiteness like in many other languages. There are two numbers: singular and plural; and six different cases: nominative, accusative, dative, locative, ablative and genitive.[40][41] Verbs are conjugated for tense: present and past; voice: causative and passive; aspect: continuous; and mood: e.g. ability. Verbs may be negated as well.[40]

Lexicon

The core lexicon of the Uyghur language is of Turkic stock, but due to different kinds of language contact through the history of the language, it has adopted many loanwords. Kazakh, Uzbek and Chagatai are all Turkic languages which have had a strong influence on Uyghur. Many words of Arabic origin have come into the language through Persian and Tajik, which again have come through Uzbek, and to a greater extent, Chagatai. Many words of Arabic origin have also entered the language directly through Islamic literature after the introduction of the Islamic religion around the 10th century.

Chinese in Xinjiang and Russian elsewhere had the greatest influence on Uyghur. Loanwords from these languages are all quite recent, although older borrowings exist as well, such as borrowings from Dungan, a Mandarin language spoken by the Dungan people of Central Asia. A number of loanwords of German origin have also reached Uyghur through Russian.[42]

Below are some examples of loanwords which have entered the Uyghur language.

| Origin | Source word | Source (in IPA) | Uyghur word | Uyghur (in IPA) | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persian | افسوس | [efˈsus] | epsus ئەپسۇس | /ɛpsus/ | pity |

| گوشت | [ɡoʃt] | gösh گۆش | /ɡøʃ/ | meat | |

| Arabic | ساعة | /ˈsaːʕat/ (genitive case) | saet سائەت | /saʔɛt/ | hour |

| Russian | велосипед | [vʲɪləsʲɪˈpʲɛt] | wëlsipit ۋېلسىپىت | /welsipit/ | bicycle |

| доктор | [ˈdoktər] | doxtur دوختۇر | /doχtur/ | doctor (medical) | |

| поезд | [ˈpo.jɪst] | poyiz پويىز | /pojiz/ | train | |

| область | [ˈobləsʲtʲ] | oblast ئوبلاست | /oblast/ | oblast, region | |

| телевизор | [tʲɪlʲɪˈvʲizər] | tëlëwizor تېلېۋىزور | /televizor/ | television set | |

| Chinese | 凉粉 liángfěn | [li̯ɑŋ˧˥fən˨˩] | lempung لەڭپۇڭ | /lɛmpuŋ/ | agar-agar jelly |

| 豆腐 dòufu | [tou̯˥˩fu˩] | dufu دۇفۇ | /dufu/ | bean curd/tofu |

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Uyghur at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Uighur". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ "Uyghur - definition of Uyghur by the Free Online Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 5 October 2013.

- ↑ "Define Uighur at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 5 October 2013.

- ↑ In English, the name of the ethnicity and its language is spelled variously as Uyghur, Uighur, Uygur and Uigur, with the preferred spelling being Uyghur.

- ↑ Its name in other languages in which it might be often referred to is as follows:

- simplified Chinese: 维吾尔语; traditional Chinese: 維吾爾語; pinyin: Wéiwú'ěryǔ in Chinese

- Уйгурский (язык) (transliteration: Uygurskiy (yazyk)) in Russian.

- ↑ Arik, Kagan (2008). Austin, Peter, ed. One Thousand Languages: Living, Endangered, and Lost (illustrated ed.). University of California Press. p. 145. ISBN 0520255607. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ↑ Clauson, Gerard (Apr 1965). "Review An Eastern Turki-English Dictionary by Gunnar Jarring". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland) (No. 1/2): 57. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ↑ Coene, Frederik (2009). The Caucasus - An Introduction. Routledge Contemporary Russia and Eastern Europe Series. Routledge. p. 75. ISBN 1135203024. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ↑ Coene, Frederik (2009). The Caucasus - An Introduction. Routledge Contemporary Russia and Eastern Europe Series (illustrated, reprint ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 75. ISBN 0203870719. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ↑ Hahn 1998, pp. 83–84

- ↑ Dankoff, Robert (March 1981), "Inner Asian Wisdom Traditions in the Pre-Mongol Period", Journal of the American Oriental Society (American Oriental Society) 101 (1): 87–95, doi:10.2307/602165, retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ↑ Brendemoen, Brett (1998), "Turkish Dialects", in Lars Johanson, Éva Csató, The Turkic languages, Taylor & Francis, pp. 236–41, ISBN 978-0-415-08200-6, retrieved 8 March 2010

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Baldick, Julian (2000), Animal and shaman: ancient religions of Central Asia, I.B. Tauris, p. 50, ISBN 978-1-86064-431-3, retrieved 8 March 2010

- ↑ Kayumov, A. (2002), "Literature of the Turkish Peoples", in C. E. Bosworth, M.S.Asimov, History of Civilizations of Central Asia 4, Motilal Banarsidass, p. 379, ISBN 978-81-208-1596-4, retrieved 8 March 2010

- ↑ "تۈركى تىللار دىۋانى پۈتۈن تۈركىي خەلقلەر ئۈچۈن ئەنگۈشتەردۇر (The Compendium of Turkic Languages was for all Turkic peoples)". Radio Free Asia (in Uyghur). 11 February 2010. Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ↑ Badīʻī, Nādira (1997), Farhang-i wāžahā-i fārsī dar zabān-i ūyġūrī-i Čīn, Tehran: Bunyād-i Nīšābūr, p. 57

- ↑ Brown, Keith; Ogilvie, Sarah (2009), "Uyghur", Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World, Elsevier, p. 1143, ISBN 978-0-08-087774-7.

- ↑ Hahn 1998, p. 379

- ↑ Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs (1991). Journal of the Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs, Volumes 12-13. King Abdulaziz University. p. 108. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Walravens, Hartmut (2006), His Life and Works with Special Emphasis on Japan (PDF), Japonica Humboldtiana 10, Harrassowitz Verlag

- ↑ Yakup 2005, p. 8

- ↑ Hahn 1991, p. 53

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Dwyer 2005, pp. 12–13

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 "Uyghur". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- ↑ "Uyghur". Omniglot. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- ↑ Hann, Chris (2011). "Smith in Beijing, Stalin in Urumchi: Ethnicity, political economy, and violence in Xinjiang, 1759-2009". Focaal—Journal of Global and Historical Anthropology (60): 112.

- ↑ Dwyer, Arienne (2005), The Xinjiang Conflict: Uyghur Identity, Language Policy, and Political Discourse (PDF), Policy Studies 15, Washington: East-West Center, pp. 12–13, ISBN 1-932728-29-5

- ↑ Hahn 1998, p. 380

- ↑ Hahn 1991, p. 34

- ↑ Vaux 2001

- ↑ Vaux 2001, pp. 1–2

- ↑ Hahn 1991, p. 89

- ↑ Hahn 1991, pp. 84–86

- ↑ Hahn 1991, pp. 82–83

- ↑ Hahn 1991, pp. 80–84

- ↑ Hahn 1998, pp. 381–382

- ↑ Hahn 1991, pp. 59–84

- ↑ Hahn 1991, pp. 22–26

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Engesæth, Yakup & Dwyer 2009, pp. 1–2

- ↑ Hahn 1991, pp. 589–590

- ↑ Hahn 1998, pp. 394–395

General

- Duval, Jean Rahman; Janbaz, Waris Abdukerim (2006), An Introduction to Latin-Script Uyghur (PDF), Salt Lake City: University of Utah (Archive)

- Dwyer, Arienne (2001), "Uyghur", in Garry, Jane; Rubino, Carl, Facts About the World's Languages, H. W. Wilson, pp. 786–790, ISBN 978-0-8242-0970-4

- Engesæth, Tarjei; Yakup, Mahire; Dwyer, Arienne (2009), Greetings from the Teklimakan: A Handbook of Modern Uyghur, Volume 1 (PDF), Lawrence: University of Kansas Scholarworks, ISBN 978-1-936153-03-9 (Archive)

- Hahn, Reinhard F. (1991), Spoken Uyghur, London and Seattle: University of Washington Press, ISBN 978-0-295-98651-7

- Hahn, Reinhard F. (1998), "Uyghur", in Johanson, Lars; Csató, Éva Ágnes, The Turkic Languages, Routledge, pp. 379–396, ISBN 978-0-415-08200-6

- Johanson, Lars, "History of Turkic", in Johanson, Lars; Csató, Éva Ágnes, The Turkic Languages, Routledge, pp. 81–125, ISBN 978-0-415-08200-6

- Vaux, Bert (2001), Disharmony and Derived Transparency in Uyghur Vowel Harmony (PDF), Cambridge: Harvard University (Archive)

- Tömür, Hamüt (2003), Modern Uyghur Grammar (Morphology), trans. Anne Lee, Istanbul: Yıldız, ISBN 975-7981-20-6

- Yakup, Abdurishid (2005), The Turfan Dialect of Uyghur, Turcologica 63, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3-447-05233-3

External links

| Uyghur edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Uyghur Arabic script. |

| Look up Uyghur in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Dictionaries

- Uyghur–Chinese Dictionary

- Online Uyghur-English Multiscript Dictionary

- Online Uyghur, English, Chinese Multi-directional Dictionary (Arabic Alphabet)

- Free Uighur Dictionary

- English/Chinese/French ↔ Uyghur translation services

Radio

Television

Fonts

- Arabic Uyghur in different fonts

- Unicode based TrueType/OpenType fonts of the Uyghur Computer Science Association

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||