Upside potential ratio

The Upside-Potential Ratio is a measure of a return of an investment asset relative to the minimal acceptable return. The measurement allows a firm or individual to choose investments which have had relatively good upside performance, per unit of downside risk.

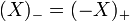

where the returns  have been put into increasing order. Here

have been put into increasing order. Here  is the probability of the return

is the probability of the return  and

and  which occurs at

which occurs at  is the minimal acceptable return. In the secondary formula

is the minimal acceptable return. In the secondary formula  and

and  .[1]

.[1]

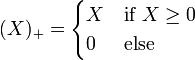

The Upside-Potential Ratio may also be expressed as a ratio of partial moments since ![\mathbb{E}[(R_r - R_\min)_+]](../I/m/b92ec080b129b27596eabd684f72cab3.png) is the first upper moment and

is the first upper moment and ![\mathbb{E}[(R_r - R_\min)_-^2]](../I/m/ae6219d8f3b37b8a861c8950b3f220a7.png) is the second lower partial moment.

is the second lower partial moment.

The measure was developed by Frank A. Sortino.

Discussion

The Upside-Potential Ratio is a measure of risk-adjusted returns. All such measures are dependent on some measure of risk. In practice, standard deviation is often used, perhaps because it is mathematically easy to manipulate. However, standard deviation treats deviations above the mean (which are desirable, from the investor's perspective) exactly the same as it treats deviations below the mean (which are less desirable, at the very least). In practice, rational investors have a preference for good returns (e.g., deviations above the mean) and an aversion to bad returns (e.g., deviations below the mean).

Sortino further found that investors are (or, at least, should be) averse not to deviations below the mean, but to deviations below some "minimal acceptable return" (MAR), which is meaningful to them specifically. Thus, this measure uses deviations above the MAR in the numerator, rewarding performance above the MAR. In the denominator, it has deviations below the MAR, thus penalizing performance below the MAR.

Thus, by rewarding desirable results in the numerator and penalizing undesirable results in the denominator, this measure attempts to serve as a pragmatic measure of the goodness of an investment portfolio's returns in a sense that is not just mathematically simple (a primary reason to use standard deviation as a risk measure), but one that considers the realities of investor psychology and behavior.

See also

- Modern portfolio theory

- Modigliani Risk-Adjusted Performance

- Omega ratio

- Sharpe ratio

- Sortino ratio

References

- ↑ Chen, L.; He, S.; Zhang, S. (2011). "When all risk-adjusted performance measures are the same: In praise of the Sharpe ratio". Quantitative Finance 11 (10): 1439. doi:10.1080/14697680903081881.

![U = {{{\sum_\min^{+\infty} {(R_r - R_\min}) P_r}} \over \sqrt{{{\sum_{-\infty}^\min {(R_r - R_\min})^2 P_r}}}} = \frac{\mathbb{E}[(R_r - R_\min)_+]}{\sqrt{\mathbb{E}[(R_r - R_\min)_-^2]}},](../I/m/02383dce3b145db8372f310bf30959ae.png)