University of Virginia

Coordinates: 38°02′06″N 78°30′18″W / 38.035°N 78.505°W

| University of Virginia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Established | 1819 |

| Type |

Public Flagship |

| Endowment | US$6.9 billion[1] |

| Budget | US$2.7 billion (2013—excludes capital spending) |

| President | Teresa A. Sullivan |

Academic staff | 2,102 |

| Undergraduates | 14,898[2] |

| Postgraduates | 6,340[2] |

| Location | Charlottesville, Virginia, United States |

| Campus |

Suburban 1,682 acres (6.81 km2) UNESCO World Heritage Site |

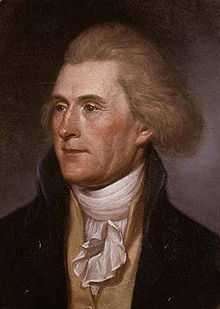

| Founder | Thomas Jefferson |

| Colors |

Orange, Blue [3] |

| Athletics | NCAA Division I – ACC |

| Sports | 25 varsity teams |

| Nickname |

Cavaliers Wahoos |

| Mascot | Cavalier |

| Affiliations |

AAU APLU ORAU URA SURA |

| Website |

www |

| |

| Official name | Monticello and the University of Virginia in Charlottesville |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iv, vi |

| Designated | 1987 (11th session) |

| Reference no. | 442 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

The University of Virginia (UVA or U.Va.), often referred to as simply Virginia, is a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. UVA is known for its historic foundations, student-run honor code, and secret societies.

Its initial Board of Visitors included U.S. Presidents Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe. Monroe was the sitting President of the United States at the time of the founding; Jefferson and Madison were the first two rectors. UVA was established in 1819, with its Academical Village and original courses of study conceived and designed entirely by Jefferson. UNESCO designated it a World Heritage Site in 1987, an honor shared with nearby Monticello.[4]

The first university of the restored American South elected to the Association of American Universities in 1904, UVA is classified as Very High Research Activity in the Carnegie Classification. The university is affiliated with 7 Nobel Laureates, and has produced 7 NASA astronauts, 7 Marshall Scholars, 4 Churchill Scholars, 29 Truman Scholars, and 50 Rhodes Scholars, the most of any state-affiliated institution in the U.S.[5][6][7] Supported in part by the Commonwealth, it receives far more funding from private sources than public, and its students come from all 50 states and 147 countries.[2][8][9] It also operates a small liberal arts branch campus in the far southwestern corner of the state.

Since 1953, Virginia's athletic teams have competed in the Atlantic Coast Conference of Division I of the NCAA and are known as the Virginia Cavaliers. Virginia won its 7th men's soccer national title in December 2014, bringing its collective total to 24 National Championships, and 63 ACC Championships since 2002 (as of 2014), the most of any conference member during that time.[6][10] US News and World Report ranks Virginia 2nd among all national public universities, tied with University of California-Los Angeles.

History

1800s

In 1802, while serving as President of the United States, Thomas Jefferson wrote to artist Charles Willson Peale that his concept of the new university would be "on the most extensive and liberal scale that our circumstances would call for and our faculties meet," and that it might even attract talented students from "other states to come, and drink of the cup of knowledge".[11] Virginia was already home to the College of William and Mary, but Jefferson lost all confidence in his alma mater, partly because of its religious nature – it required all its students to recite a catechism – and its stifling of the sciences.[12][13] Jefferson had flourished under William & Mary professors William Small and George Wythe decades earlier, but the college was in a period of great decline and his concern became so dire by 1800 that he expressed to British chemist Joseph Priestley, "we have in that State, a college just well enough endowed to draw out the miserable existence to which a miserable constitution has doomed it."[12][14][15] These words would eventually ring true when William and Mary fell bankrupt after the Civil War and shut down completely in 1881, later being revived as a small teacher's college.[16]

Farmland just outside Charlottesville was purchased from James Monroe by the Board of Visitors as Central College in 1817. The school laid its first building's cornerstone in late 1817, and the Commonwealth of Virginia chartered the new university on January 25, 1819. John Hartwell Cocke collaborated with James Madison, Monroe, and Joseph Carrington Cabell to fulfill Jefferson's dream to establish the university. Cocke and Jefferson were appointed to the building committee to supervise the construction.[17] The university's first classes met on March 7, 1825.[18]

In contrast to other universities of the day, at which one could study in either medicine, law, or divinity, the first students at the University of Virginia could study in one or several of eight independent schools – medicine, law, mathematics, chemistry, ancient languages, modern languages, natural philosophy, and moral philosophy.[19] Another innovation of the new university was that higher education would be separated from religious doctrine. UVA had no divinity school, was established independently of any religious sect, and the Grounds were planned and centered upon a library, the Rotunda, rather than a church, distinguishing it from peer universities still primarily functioning as seminaries for one particular strain of Protestantism or another.[20] Jefferson opined to philosopher Thomas Cooper that "a professorship of theology should have no place in our institution", and never has there been one. There were initially two degrees awarded by the university: Graduate, to a student who had completed the courses of one school; and Doctor to a graduate in more than one school who had shown research prowess.[21]

Jefferson was intimately involved in the university to the end, hosting Sunday dinners at his Monticello home for faculty and students until his death. So taken with the import of what he viewed the university's foundations and potential to be, and counting it amongst his greatest accomplishments, Jefferson insisted his grave mention only his status as author of the Declaration of Independence and Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, and father of the University of Virginia. Thus, he eschewed mention of his national accomplishments, such as the Louisiana Purchase, in favor of his role with the young university.

In the year of Jefferson's death, poet Edgar Allan Poe enrolled at the university, where he excelled in Latin.[22] The Raven Society, an organization named after Poe's most famous poem, continues to maintain 13 West Range, the room Poe inhabited during the single semester he attended the university.[23] He left because of financial difficulties. The School of Engineering and Applied Science opened in 1836, making UVA the first comprehensive university to open an engineering school.

Unlike the vast majority of peer colleges in the South, the university was kept open throughout the Civil War, an especially remarkable feat with its state seeing more bloodshed than any other and the near 100% conscription of the entire American South.[24] After Jubal Early's total loss at the Battle of Waynesboro, Charlottesville was willingly surrendered to Union forces to avoid mass bloodshed and UVA faculty convinced George Armstrong Custer to preserve Jefferson's university.[25] Though Union troops camped on the Lawn and damaged many of the Pavilions, Custer's men left four days later without bloodshed and the university was able to return to its educational mission. However, an extremely high number of officers of both Confederacy and Union were alumni.[26] UVA produced 1,481 officers in the Confederate Army alone, including four major-generals, twenty-one brigadier-generals, and sixty-seven colonels from ten different states.[26] John S. Mosby, the infamous "Gray Ghost" and commander of the lightning-fast 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry ranger unit, had also been a UVA student.

| Wikisource has the text of an 1879 American Cyclopædia article about University of Virginia. |

Thanks to a grant from the Commonwealth of Virginia, tuition became free for all Virginians in 1875.[27] During this period the University of Virginia remained unique in that it had no president and mandated no core curriculum from its students, who often studied in and took degrees from more than one school.[27] However, the university was also experiencing growing pains. As the original Rotunda caught fire and burned to the ground in 1895, there would soon be sweeping change afoot.

1900s

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Jefferson had originally decided that the University of Virginia would have no president. Rather, this power was to be shared by a rector and a Board of Visitors. But as the 19th century waned, it became obvious this cumbersome arrangement was incapable of adequately handling the many administrative and fundraising tasks of the growing university.[28] Edwin Alderman, who had only recently moved from his post as president of UNC-Chapel Hill since 1896 to become president of Tulane University in 1900, accepted an offer as president of the University of Virginia in 1904. His appointment was not without controversy, and national media such as Popular Science lamented the end of one of the things that made UVA unique among universities.[29]

Alderman would stay twenty-seven years, and became known as a prolific fund-raiser, a well-known orator, and a close adviser to U.S. President and UVA alumnus Woodrow Wilson.[28] He added significantly to the University Hospital to support new sickbeds and public health research, and helped create departments of geology and forestry, the Curry School of Education, the McIntire School of Commerce, and the summer school programs at which a young Georgia O'Keeffe would soon take art.[30] Perhaps his greatest ambition was the funding and construction of a library on a scale of millions of books, much larger than the Rotunda could bear. Delayed by the Great Depression, Alderman Library was named in his honor in 1938. Alderman, who seven years earlier had died in office en route to giving a public speech at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, is still the longest-tenured president of the university.

In 1904, the University of Virginia became the first university in the American South to be elected to the prestigious Association of American Universities. After a gift by Andrew Carnegie in 1909 the University of Virginia was organized into twenty-six departments including the Andrew Carnegie School of Engineering, the James Madison School of Law, the James Monroe School of International Law, the James Wilson School of Political Economy, the Edgar Allan Poe School of English and the Walter Reed School of Pathology.[21] The honorific historical names for these departments are no longer used.

The University of Virginia established a junior college in 1954, then called Clinch Valley College. Today it is a four-year public liberal arts college called the University of Virginia's College at Wise and currently enrolls 2,000 students.

The University of Virginia began the process of integration even before the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision mandated school desegregation for all grade levels, when Gregory Swanson sued to gain entrance into the university's law school in 1950.[31] Following his successful lawsuit, a handful of black graduate and professional students were admitted during the 1950s, though no black undergraduates were admitted until 1955, and UVA did not fully integrate until the 1960s.[31]

The university first admitted a few selected women to graduate studies in the late 1890s and to certain programs such as nursing and education in the 1920s and 1930s.[32] In 1944, Mary Washington College in Fredericksburg, Virginia, became the Women's Undergraduate Arts and Sciences Division of the University of Virginia. With this branch campus in Fredericksburg exclusively for women, UVA maintained its main campus in Charlottesville as near-exclusively for men, until a civil rights lawsuit of the 1960s forced it to commingle the sexes.[33] In 1970, the Charlottesville campus became fully co-educational, and in 1972 Mary Washington became an independent state university.[34] When the first female class arrived, 450 undergraduate women entered UVA, comprising 39 percent of undergraduates, while the number of men admitted remained constant. By 1999, women made up a 52 percent majority of the total student body.[32][35]

2000s

Due to a continual decline in state funding for the university, today only 6% of its budget comes from the Commonwealth of Virginia.[36] A Charter initiative was signed into law by then-Governor Mark Warner in 2005, negotiated with the university to have greater autonomy over its own affairs in exchange for accepting this decline in financial support.[37][38]

The university welcomed Teresa A. Sullivan as its first female president in 2010.[39] Just two years later its first woman rector, Helen Dragas, engineered a forced-resignation to remove President Sullivan from office.[40][41] The forced resignation elicited strong protests, including a faculty Senate vote of no confidence in the Board of Visitors and Rector Dragas, and demands from the student government for an explanation for Sullivan's ouster.[42][43] In addition the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools put UVA on warning that the nature of the ouster of President Sullivan could put the school's accreditation at risk.[44]

In the face of mounting pressure, including alumni threats to cease contributions and a mandate from then-Governor Robert McDonnell to resolve the issue or face removal of the entire Board of Visitors, the Board unanimously voted to reinstate President Sullivan.[45][46][47] In 2013 and 2014, the Board passed new bylaws that made it harder to remove a president, and considered one to make it possible to remove a rector.[48]

In November 2014, the university suspended all fraternity and sorority functions for six weeks pending investigation of an article by Rolling Stone concerning the university's handling of alleged rape cases. In December 2014 the magazine made multiple apologies to "anyone who was affected," citing discrepancies in its principal source and the inability to verify key facts.[49][50] The university lifted the fraternity suspension after instituting new rules banning "pre-mixed drinks, punches or any other common source of alcohol” such as beer kegs and requiring "sober and lucid" fraternity members to monitor parties.[51] On April 5, 2015, Rolling Stone fully retracted the article after the Columbia School of Journalism released a report of "what went wrong" with the article and the Charlottesville Police had earlier found discrepancies in the alleged victim's account.[52][53]

Campus

Academical Village

- See also: The Lawn, The Rotunda, and The Range

Throughout its history, the University of Virginia has won praise for its unique Jeffersonian architecture. In January 1895, less than a year before the Great Rotunda Fire, The New York Times said that the design of the University of Virginia "was incomparably the most ambitious and monumental architectural project that had or has yet been conceived in this century."[54] In the United States Bicentennial issue of their AIA Journal, the American Institute of Architects called it "the proudest achievement of American architecture in the past 200 years."[55]

Jefferson's original architectural design revolves around the Academical Village, and that name remains in use today to describe both the specific area of the Lawn, a grand, terraced green space surrounded by residential and academic buildings, the gardens, the Range, and the larger university surrounding it. The principal building of the design, the Rotunda, stands at the north end of the Lawn, and is the most recognizable symbol of the university. It is half the height and width of the Pantheon in Rome, which was the primary inspiration for the building. The Lawn and the Rotunda were the model for many similar designs of "centralized green areas" at universities across the country. The space was designed for students and professors to live in the same area. The Rotunda, which symbolized knowledge, showed hierarchy. The south end of the lawn was left open to symbolize the view of cultivated fields to the south, as reflective of Jefferson's ideal for an agrarian-focused nation.

Most notably designed by inspiration of the Rotunda and Lawn are the expansive green spaces headed by similar buildings built at: Duke University in 1892; Columbia University in 1895; Johns Hopkins University in 1902; Rice University in 1910; Peabody College of Vanderbilt University in 1915; Killian Court at MIT in 1916; the Grand Auditorium of Tsinghua University built in 1917 in Beijing, China; the Sterling Quad of Yale Divinity School in 1932; and the university's own Darden School in 1996.

Flanking both sides of the Rotunda and extending down the length of the Lawn are ten Pavilions interspersed with student rooms. Each has its own classical architectural style, as well as its own walled garden separated by Jeffersonian Serpentine walls. These walls are called "serpentine" because they run a sinusoidal course, one that lends strength to the wall and allows for the wall to be only one brick thick, one of many innovations by which Jefferson attempted to combine aesthetics with utility. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr., a former scholar at the university, has written the definitive book on the original academic buildings at the university.[56]

On October 27, 1895, the Rotunda burned to a shell because of an electrical fire that started in the Rotunda Annex, a long multi-story structure built in 1853 to house additional classrooms. The electrical fire was no doubt assisted by the unfortunate help of overzealous faculty member William "Reddy" Echols, who attempted to save it by throwing roughly 100 pounds (45 kg) of dynamite into the main fire in the hopes that the blast would separate the burning Annex from Jefferson's own Rotunda. His last-ditch effort ultimately failed. Perhaps ironically, one of the university's main honors student programs is named for him. University officials swiftly approached celebrity architect Stanford White to rebuild the Rotunda. White took the charge further, disregarding Jefferson's design and redesigning the Rotunda interior—making it two floors instead of three, adding three buildings to the foot of the Lawn, and designing a president's house. He did omit rebuilding the Rotunda Annex, the remnants of which were used as fill and to create part of the modern-day Rotunda's northern-facing plaza. The classes formerly occupying the Annex were moved to the South Lawn in White's new buildings.

The White buildings have the effect of closing off the sweeping perspective, as originally conceived by Jefferson, down the Lawn across open countryside toward the distant mountains. The White buildings at the foot of the Lawn effectively create a huge "quadrangle", albeit one far grander than any traditional college quadrangle at the University of Cambridge or University of Oxford.

In concert with the United States Bicentennial in 1976, Stanford White's changes to the Rotunda were removed and the building was returned to Jefferson's original design. Renovated according to original sketches and historical photographs, a three-story Rotunda opened on Jefferson's birthday, April 13, 1976. Queen Elizabeth II came to visit the Rotunda in that same year for the Bicentennial, and had a well-publicized stroll of The Lawn.

The university, together with Jefferson's home at Monticello, is a World Heritage Site, one of only three modern man-made sites so listed in the U.S. with the Statue of Liberty and Independence Hall. The first collegiate World Heritage Site in the world, it was codified as such by UNESCO in 1987. The university was listed by Travel + Leisure in September 2011 as one of the most beautiful campuses in the United States and by MSN as one of the most beautiful college campuses in the world.[57][58]

Libraries

The University of Virginia Library System holds 5 million volumes. Its Electronic Text Center, established in 1992, has put 70,000 books online as well as 350,000 images that go with them. These e-texts are open to anyone and, as of 2002, were receiving 37,000 daily visits (compared to 6,000 daily visitors to the physical libraries).[59] Alderman Library holds the most extensive Tibetan collection in the world, and holds ten floors of book "stacks" of varying ages and historical value. The renowned Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library features one of the premier collections of American Literature in the country as well as two copies of the original printing of the Declaration of Independence. It was in this library in 2006 that Robert Stilling, an English graduate student, discovered an unpublished Robert Frost poem from 1918.[60] Clark Hall is the library for SEAS (the engineering school), and one of its notable features is the Mural Room, decorated by two three-panel murals by Allyn Cox, depicting the Moral Law and the Civil Law. The murals were finished and set in place in 1934.[61] As of 2006, the university and Google were working on the digitization of selected collections from the library system.[62]

Since 1992, the University of Virginia also hosts the Rare Book School, a non-profit organization in study of historical books and the history of printing that began at Columbia University in 1983.

Other areas

Housing for first-year students, Brown College, the School of Engineering and Applied Science and the University of Virginia Medical School are located near the historic Lawn and Range area. The McIntire School of Commerce is situated on the actual Lawn, in Rouss Hall.

Away from the historic area, UVA's architecture and its allegiance to the Jeffersonian design are controversial. The 1990s saw the construction of two deeply contrasting visions: the Williams Tsien post-modernist Hereford College in 1992 and the unapologetically Jeffersonian Darden School of Business in 1996. Commentary on both was broad and partisan, as the University of Virginia School of Architecture and The New York Times lauded Hereford for its bold new lines, while some independent press and wealthy donors praised the traditional design of Darden.[63][64] The latter group appeared to have largely won the day when the South Lawn Project was designed in the early 2000s.[64][65]

Billionaire John Kluge donated 7,379 acres (29.86 km2) of additional lands to the university in 2001. Kluge desired the core of the land, the 2,913-acre Morven, to be developed by the university and the surrounding land to be sold to fund an endowment supporting the core. Five farms totaling 1,261 acres of the gift were soon sold to musician Dave Matthews, of the Dave Matthews Band, to be utilized in an organic farming project to complement his nearby Blenheim Vineyards.[66] Morven has since hosted the Morven Summer Institute, a rigrous immersion program of study in civil society, sustainability, and creativity.[67] As of 2014, the university is developing further plans for Morven and has hired an architecture firm for the nearly three thousand acre property.[67]

The Virginia Department of Transportation maintains the roads through the university grounds as State Route 302.[68]

Student housing

- Main article: Student housing at the University of Virginia

The primary housing areas for first-year students are McCormick Road Dormitories, often called "Old Dorms," and Alderman Road Dormitories, often called "New Dorms." The New Dorms are in the process of being fully replaced with brand new dormitories that feature hall-style living arrangements with common areas and many modern amenities. Instead of being torn down and replaced like the original New Dorms, the Old Dorms will see a $105 million renovation project between 2017 and 2022.[69] They were constructed in 1950, and are also hall-style constructions but with fewer amenities. However, generally the Old Dorms are closer to the students' classes.

There are three residential colleges at the university: Brown College, Hereford College, and the International Residential College. These involve an application process to live there, and are filled with both upperclass and first year students. The application process can be extremely competitive, especially for Brown.

It is considered a great honor to be invited to live on The Lawn, and 54 fourth-year undergraduates do so each year, joining ten members of the faculty who permanently live and teach in the Pavilions there.[70] Similarly, graduate students may live on The Range.

Organization and administration

The university has several affiliated centers including the Rare Book School, headquarters of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, University of Virginia Center for Politics, Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service, Sorensen Institute for Political Leadership, and Miller Center of Public Affairs. The Fralin Museum of Art is dedicated to creating an environment where both the university community and the general public can study and learn from directly experiencing works of art. The university has its own internal recruiting firm, the Executive Search Group and Strategic Resourcing. Since 2013, this department has been housed under the Office of the President.

In 2013, UVA's endowment was $5.2 billion, ranking sixteenth among all singular (non-systemwide) colleges and universities in North America, and second among publics.[71] In 2014, the endowment was $6.949 billion.[1]

| College/school founding | |

|---|---|

| College/school | Year founded |

| School of Architecture | 1954 |

| College of Arts & Sciences | 1824 |

| Darden School of Business | 1954 |

| McIntire School of Commerce | 1921 |

| School of Continuing and Professional Studies | |

| Curry School of Education | 1905 |

| School of Engineering and Applied Science | 1836 |

| School of Law | 1819 |

| School of Medicine | 1819 |

| School of Nursing | 1901 |

| Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy | 2007 |

In 2006, then-President Casteen announced an ambitious $3 billion capital campaign to be completed by December 2011.[72] During the Great Recession, President Sullivan missed the 2011 deadline, and extended it indefinitely.[73] The $3 billion goal would be met a year and a half later, which President Sullivan announced at graduation ceremonies in May 2013.[74]

As of 2013, UVA's $1.4 billion academic budget is paid for primarily by tuition and fees (32%), research grants (23%), endowment and gifts (19%), and sales and services (12%).[75] A mere 10% of academic funds come from state appropriation from the Commonwealth of Virginia.[75] For the overall (including non-academic) university budget of $2.6 billion, 45% comes from medical patient revenue.[75] The Commonwealth contributes less than 6%.[75]

Though UVA is the flagship university of Virginia, state funding has decreased for several consecutive decades.[36] Financial support from the state dropped by half from 12 percent of total revenue in 2001-02 to 6 percent in 2013-14.[36] The portion of academic revenue coming from the state fell by even more in the same period, from 22 percent to just 9 percent.[36] This nominal support from the state, contributing just $154 million of UVA's $2.6 billion budget in 2012-13, has led President Sullivan and others to contemplate the partial privatization of the University of Virginia.[76] A panel called the Public University Working Group concluded in 2013 that UVA should sever many of its ties with the Commonwealth of Virginia in order to further advance its academic standing.[76]

Hunter R. Rawlings III, President of the prominent Association of American Universities research group of universities to which UVA is an elected member, came to Charlottesville to make a speech to university faculty which included a statement about the proposal: "there's no possibility, as far as I can see, that any state will ever relinquish its ownership and governance of its public universities, much less of its flagship research university".[76] He encouraged university leaders to stop talking about privatization and instead push their state lawmakers to increase funding for higher education and research as a public good.[76]

The University of Virginia is one of only two public universities in the United States that has a Triple-A credit rating from all three major credit rating agencies, along with the University of Texas at Austin.[77]

Academics

UVA offers 48 bachelor's degrees, 94 master's degrees, 55 doctoral degrees, 6 educational specialist degrees, and 2 first-professional degrees (Medicine and Law) to its students. It has never bestowed honorary degrees.[78][79][80]

The Jefferson Scholars Foundation offers four-year full-tuition scholarships based on regional, international, and at-large competitions. Students are nominated by their high schools, interviewed, then invited to weekend-long series of tests of character, aptitude, and general suitability. Approximately 3% of those nominated successfully earn the scholarship. Echols Scholars (College of Arts and Sciences) and Rodman Scholars (School of Engineering and Applied Sciences), which include 6-7% of undergraduate students, receive no financial benefits, but are entitled to special advisors, priority course registration, residence in designated dorms and fewer curricular constraints than other students.[81]

Research

As of 2012, UVA received $218,499,000 in prestigious U.S. federal research grants, the most of any university in Virginia.[82] Since 1904, UVA has been an elected member of the Association of American Universities – a prominent organization of leading North American research universities.

In the field of astrophysics, the university is a member of a consortium engaged in the construction and operation of the Large Binocular Telescope in the Mount Graham International Observatory of the Pinaleno Mountains of southeastern Arizona. It is also a member of both the Astrophysical Research Consortium, which operates telescopes at Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico, and the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy which operates the National Optical Astronomy Observatory, the Gemini Observatory and the Space Telescope Science Institute. The University of Virginia hosts the headquarters of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, which operates the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia and the Very Large Array radio telescope made famous in the Carl Sagan television documentary Cosmos and film Contact. The North American Atacama Large Millimeter Array Science Center is also located at the Charlottesville NRAO site.

Rankings

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| ARWU[83] | 53-64 |

| Forbes[84] | 29 |

| U.S. News & World Report[85] | 23 |

| Washington Monthly[86] | 51 |

| Global | |

| ARWU[87] | 101-150 |

| QS[88] | 132 |

| Times[89] | 112 |

U.S. News & World Report ranks UVA tied for #23 overall and #2 among publics. Among the professional schools of UVA, as of 2014 U.S. News ranks its law school #8 overall and #1 among publics, its graduate Darden School of Business tied for #11 overall and #2 among publics, and its medical school #26 overall and #8 among publics in the Research category.[90][91][92] The Economist ranks Darden #4 worldwide and #2 among publics.[93] Bloomberg BusinessWeek ranks the undergraduate McIntire School of Commerce #2 overall and #1 among publics.[94]

The Daily Caller ranks UVA the #1 overall U.S. university and "the best school in the land" as of 2014 with such factors as professor ratings, total cost, and student attractiveness added to more traditional data points.[95] Business Insider, striving to measure preparation for the professional workforce, ranks UVA #19 overall and #2 among publics.[96]

Recognition

A National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) study of "high-achieving" undergraduate applicants found UVA to be the highest preference for these students among public universities of the United States in December 2005, noting that "all of the top twenty, except for the University of Virginia, are private institutions."[97] "High-achieving" applicants were defined as those ranking at or near the top of their classes at 510 outstanding high schools across the country.[97]

The University of Virginia has been recognized for consistently having the highest African American graduation rate among national public universities.[98][99][100][101] According to the Fall 2005 issue of Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, UVA "has the highest black student graduation rate of the Public Ivies" and "by far the most impressive is the University of Virginia with its high black student graduation rate and its small racial difference in graduation rates."[102]

Admissions and financial aid

For the undergraduate Class of 2018, the University of Virginia received 31,042 applications, admitting 28.9 percent.[103] The university has seen steady increases in the applicant pool throughout the past decade, and the number of applications has more than doubled since the Class of 2008 received 15,094 applications.[104] Interested applicants may arrange an overnight visit through the Monroe Society, a student-run organization.[9] In 2014, 93% of admitted applicants ranked in the top 10 percent of their high school classes.[9][103] Matriculated students come from all 50 states and 147 foreign countries.[2][9] The average LSAT score was 169 at the School of Law, while at the Darden School of Business the average GMAT score was 706.[105][106]

UVA meets 100 percent of demonstrated need for all admitted undergraduate students, making it one of only two public universities in the U.S. to reach this level of financial aid for its students.[107][108] For 2014, the university ranked #4 overall by the Princeton Review for "Great Financial Aid".[109] In 2008 the Center for College Affordability and Productivity named UVA the top value among all national public colleges and universities; and in 2009, UVA was again named the "#1 Best Value" among public universities in the United States in a separate ranking by USA TODAY and the Princeton Review.[110][111][112] Kiplinger in 2014 ranked UVA #2 out of the top 100 best-value public colleges and universities in the nation.[113]

Student life

Student life at the University of Virginia is marked by a number of unique traditions. The campus of the university is referred to as "the Grounds". Freshmen, sophomores, juniors, and seniors are instead called first-, second-, third-, and fourth-years in order to reflect Jefferson's belief that learning is a never-ending process, rather than one to be completed within four years. Also, students do not "graduate" from the university; instead, they "take" their degrees. Professors are traditionally addressed as "Mr." or "Ms." instead of "Doctor" (although medical doctors are the exception and are called "Doctor") in deference to Jefferson's desire to have an equality of ideas, discriminated by merit and unburdened by title.

In 2005, the university was named "Hottest for Fitness" by Newsweek magazine,[114] due in part to 94% of its students using one of the four indoor athletics facilities. Particularly popular is the Aquatics and Fitness Center, situated across the street from the Alderman Dorms. The University of Virginia sent more workers to the Peace Corps in 2006[115] and 2008[116] than any other "medium-sized" university in the United States. Volunteerism at the university is centered in Madison House which offers numerous opportunities to serve others. Among the numerous programs offered are tutoring, housing improvement, and an organization called Hoos Against Hunger, which gives leftover food from restaurants to the homeless of Charlottesville, rather than allowing it to be discarded.

Secret societies

A number of secret societies at the university, most notably the Seven Society, Z Society, and IMP Society, have operated for decades or centuries, leaving their painted marks on university buildings. Other significant secret societies include Eli Banana, T.I.L.K.A., the Purple Shadows (who commemorate Jefferson's birthday shortly after dawn on the Lawn each April 13), The Sons of Liberty, and the 21 Society. Not all the secret societies keep their membership unknown, but even those who don't hide their identities generally keep most of their good works and activities far from the public eye.

The student life building on the University of Virginia is called Newcomb Hall. It is home to the Student Activities Center (SAC) and the Media Activities Center (MAC), where student groups can get leadership consulting and use computing and copying resources, as well as several meeting rooms for student groups. Student Council, the student self-governing body, holds meetings Tuesdays at 6 p.m. in the Newcomb South Meeting Room. Student Council, or "StudCo", also holds office hours and regular committee meetings in the newly renovated Newcomb Programs and Council (PAC) Room. The PAC also houses the University Programs Council and Class Councils. Newcomb basement is home to both the office of the independent student newspaper The Declaration, The Cavalier Daily, and the Consortium of University Publications.

Student societies have existed on grounds since the early 19th Century. The Jefferson Literary and Debating Society, founded in 1825, is the second oldest Greek-Lettered organization in the nation (the oldest being the Phi Beta Kappa honor fraternity). It continues to meet every Friday at 7:29 PM in Jefferson Hall. The Washington Literary Society and Debating Union also meets every week, and the two organizations often engage in a friendly rivalry. In the days before social fraternities existed and intercollegiate athletics became popular, these societies were often the focal point of social activity on grounds.[117] Several fraternities were later founded at UVA including Pi Kappa Alpha in 1868, and Kappa Sigma in 1869. Many of these fraternities are located on Rugby Road.

As at many universities, alcohol use is a part of the social life of many undergraduate students. Concerns particularly arose about a past trend of seniors consuming excessive alcohol during the day of the last home football game.[118] President Casteen announced a $2.5 million donation from Anheuser-Busch to fund a new UVA-based Social Norms Institute in September 2006.[119] A spokesman said: "the goal is to get students to emulate the positive behavior of the vast majority of students". On the other hand, the university was ranked first in Playboy's 2012 list of Top 10 Party Schools based on ratings of sex, sports, and nightlife.[120]

Honor system

"On my honor, I have neither given nor received aid on this assignment."[121]

The nation's first codified honor system was instituted by UVA law professor Henry St. George Tucker, Sr. in 1842, after a fellow professor was shot to death on The Lawn. There are three tenets to the system: students simply must not lie, cheat, or steal. It is a "single sanction system," meaning that committing any of these three offenses will result in expulsion from the university. If accused, students are tried before their peers – fellow students, never faculty, serve as counsel and jury.

The honor system is intended to be student-run and student-administered.[122] Although Honor Committee resources have been strained by mass cheating scandals such as a case in 2001 of 122 suspected cheaters in a single course, and federal lawsuits have challenged the system, its verdicts are rarely overturned.[123][124][125] There is only one documented case of direct UVA administration interference in an honor system proceeding: the trial and subsequent retrial of Christopher Leggett.[126]

Student events

One of the largest events at the University of Virginia is Springfest, hosted by the University Programs Council. It takes place every year in the spring, and features a large free concert, various inflatables and games. Another popular event is Foxfield, a steeplechase and social gathering that takes place nearby in Albemarle County in April, and which is annually attended by thousands of students from the University of Virginia and neighboring colleges.[127]

Transportation

Charlottesville Union Station is located just 0.6 miles (0.97 km) from the University of Virginia, and energy efficient Amtrak passenger trains serve Charlottesville on three routes: the Cardinal (Chicago to New York City), Crescent (New Orleans to New York City), and Northeast Regional (Virginia to Boston). The long-haul Cardinal operates three times a week, while the Crescent and Northeast Regional both run daily. Charlottesville–Albemarle Airport, 8 miles (13 km) away, has nonstop flights to Chicago, New York, Atlanta, Charlotte, and Philadelphia. The larger Richmond International Airport is 77 miles (124 km) to the southeast, and the still larger Dulles International Airport is 99 miles (159 km) to the northeast. The Starlight Express offers direct express bus service from Charlottesville to New York City, and I-64 and U.S. 29, both major highways, are frequently trafficked.

Athletics

Virginia's athletic teams have been the Cavaliers since 1923, predating the NBA's Cleveland Cavaliers by five decades, and have competed in the Atlantic Coast Conference since 1953. The current Athletic Director of Virginia is Craig Littlepage. Since 2002, the Cavaliers have won 63 ACC titles, the most in the conference. Virginia also places highly in the yearly NACDA Directors' Cup program-wide national standings: taking third place in 2009-10, and finishing fourth in 2013-14.

The program has won 24 team national championships, including those in men's soccer (7), men's lacrosse (7), women's lacrosse (3), men's boxing (2), women's crew (2), women's cross country (2), and men's tennis (1). Twenty-two of those have occurred with NCAA oversight and affiliation, making Virginia the second most-winning program in the ACC.[128] Additionally, the program has won five (of the past six) indoor tennis national championships, and a track and field team title.

The most visible and widely attended sports are football, basketball, baseball, and soccer. The facilities for these sports are some of the best in the NCAA, and include Scott Stadium, John Paul Jones Arena, Davenport Field, and Klöckner Stadium. Each of these programs, except football, have seen a high standard of success in the twenty-first century, with men's basketball, baseball, and men's soccer all finishing in the top four nationally, either by final poll or post-season tournament, during the 2013-14 year.[129][130][131] The following year, UVA defeated UCLA for its seventh men's soccer national title in the 2014 College Cup, while the women's squad also reached the national championship game in the same season before falling to Florida State.[132][133]

Rivalries

Official ACC designated rivalry games include the Virginia-Virginia Tech rivalry and the brand new Virginia-Louisville rivalry against the Louisville Cardinals. These two rivalries are guaranteed a home-and-away game each year in all sports but football, in which there is a guaranteed annual game. Against the Virginia Tech Hokies, this is for the Commonwealth Cup, which Virginia has not seen for 15 of the past 16 years even as it has been on the winning end of the vast majority of other sports. The program is also a part of the more evenly balanced South's Oldest Rivalry against the North Carolina Tar Heels, a rivalry game which a sitting President of the United States, Calvin Coolidge, once attended in Charlottesville.

The Cavaliers routed the Hokies in an all-sports challenge called the Commonwealth Challenge between 2005 and 2007: 14½ to 7½ in the first year and 14 to 8 in the second. The competition was then dropped for fear of sending a wrong message following the Virginia Tech massacre. The rivalry has been renewed and altered for 2014-15, renamed the Commonwealth Clash and sponsored by the Virginia 529 College Savings Plan.[134] The point system changes of the Clash may make it more competitive than the Challenge.[135] For instance: in the convincing victories for UVA over Virginia Tech in the Challenge, college basketball was worth 4 points and track and field was worth 2; in the Clash, basketball is reduced to 2 points and track and field is boosted to 4.[136][137]

Fight song

The Cavalier Song is the University of Virginia's fight song. The song was a result of a contest held in 1923 by the university. The Cavalier Song, with lyrics by Lawrence Haywood Lee, Jr., and music by Fulton Lewis, Jr., was selected as the winner.[138] Generally the second half of the song is played during sporting events. Until the 2008 football season, the entire fight song could be heard during the Cavalier Marching Band's entrance at home football games.

Even older, the Good Ole Song dates to 1893 and though not a fight song is the de facto alma mater. It is set to the music of Auld Lang Syne and is sung after each victory in any sport, and after each touchdown in football.

People

Faculty

The university's faculty includes a Pulitzer Prize winner and former United States Poet Laureate, 25 Guggenheim fellows, 26 Fulbright fellows, six National Endowment for the Humanities fellows, two Presidential Young Investigator Award winners, three Sloan award winners, three Packard Foundation Award winners, and a winner of the 2005 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.[139] Physics professor James McCarthy was the lead academic liaison to the government in the establishment of SURANET, and the university has also participated in ARPANET, Abilene, Internet2, and Lambda Rail. On March 19, 1986, the University's domain name, Virginia.edu, became the first registration under the .edu top-level domain originating from the Commonwealth of Virginia.[140]

Faculty were originally housed in the Academical Village among the students, serving as both instructors and advisors, continuing on to include the McCormick Road Old Dorms, though this has been phased out in favor of undergraduate student resident advisors (RAs). Several of the faculty, however, continue the university tradition of living on Grounds, either on the Lawn in the various Pavilions, or as fellows at one of three residential colleges (Brown College at Monroe Hill, Hereford College, and the International Residential College).

Some of the University of Virginia's faculty have become well-known national personalities during their time in Charlottesville. Larry Sabato has, according to The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post, become the most-cited professor in the country by national and regional news organizations, both on the Internet and in print.[141] Civil rights activist Julian Bond, a professor in the Corcoran Department of History from 1990 until his retirement in 2012, was the Chairman of the NAACP from 1998 to 2009. Bond was also chosen to be the moderator of the 1998 Nobel Laureates Conferences, Media Studies and Law professor Siva Vaidhyanathan, an expert in copyright law and Internet issues, moved from New York University to the University of Virginia in 2007. Professor of Spanish David Gies received the Order of Isabella the Catholic from King Juan Carlos I of Spain in 2007.[142] 1987 Pulitzer Prize for poetry recipient Rita Dove, professor in the English department since 1989, served as United States Poet Laureate from 1993 to 1995, and has since received the National Humanities Medal from President Clinton and the National Medal of Arts from President Obama.[143]

1990 to 2012

Civil Rights Movement activist

1835 to 1853

Founder of MIT

1967 to 1971

United States Supreme Court Justice

1841 to 1845

Wrote the first honor pledge

In 2002, the Cavalier Daily student newspaper began annually posting faculty compensation online.[144]

Alumni

As of December 2014 the University of Virginia has 221,000 living graduates.[145] According to a study by researchers at the Darden School and Stanford University, UVA alumni have founded over 65,000 companies which have employed 2.3 million people worldwide with annual global revenues of $1.6 trillion.[145] Extrapolated numbers show companies founded by UVA alumni have created 371,000 jobs in the state of Virginia alone.[145] The relatively small amount that the Commonwealth gives UVA for support was determined by the study to have a tremendous return on investment for the state.[145]

Among the individuals who have attended or graduated from the University of Virginia are the founders of reddit (Steve Huffman and current Y Combinator partner Alexis Ohanian),[146] author Edgar Allan Poe,[147] Nobel Laureate James M. Buchanan, medical researcher Walter Reed,[148] painter Georgia O'Keeffe,[149] polar explorer Richard Byrd,[150] computer scientist John Backus,[151] pioneer kidney transplant surgeon J. Hartwell Harrison,[152] seven NASA astronauts (Patrick G. Forrester,[153] Karl Gordon Henize,[154] Thomas Marshburn,[155] Leland Melvin,[156] Bill Nelson,[157] Kathryn C. Thornton,[158] and Jeff Wisoff[159]), NASA Launch Director Michael D. Leinbach,[160]deep sea vent researcher Richard Lutz,[161] Pulitzer Prize-winning poets Karl Shapiro[160] and Henry S. Taylor,[160] short story writer Breece D'J Pancake,[162] Director of the National Institutes of Health Francis Collins, journalist Katie Couric,[160] journalist Margaret Brennan,[160] author David Nolan,[163] comedian and creator of 30 Rock Tina Fey,[160] film director Tom Shadyac, author Barbara A. Perry,[164] musician Boyd Tinsley,[165] billionaire commodity trader Paul Tudor Jones, venture capitalist Mansoor Ijaz,[160] founder of Landmark Communications Frank Batten,[160] novelist Robert Miskimon, influential indie rock artist Stephen Malkmus,[160] hip-hop artist and Peabody Award winner Asheru,[166] TV personality Vern Yip,[167] TV political commentator Michael Shure.,[168] and scholar and academic administrator Valerie Smith.[169]

Notable athletes who have attended or graduated from the University of Virginia include three-time NCAA Player of the Year for men's basketball Ralph Sampson,[160] pro wrestler Virgil,[170] three-time Olympic Gold Medalist for women's basketball Dawn Staley,[160] NFL Pro Bowlers Thomas Jones,[171]Ronde Barber,[160] Tiki Barber,[160] and James Farrior;[172] professional baseball players Mark Reynolds and Ryan Zimmerman,[160] Olympic medalist Wyatt Allen,[160] and Indian tennis player Somdev Devvarman.[173] The University of Virginia has been home to several top soccer players throughout the years—several former UVA players have gone on to play for the United States men's national soccer team, including Tony Meola,[174] Jeff Agoos,[175] and former USA team captains Claudio Reyna[176] and John Harkes.[177] Nikki Krzysik went on to play soccer professionally in the WPS and NWSL.[178]

Numerous political leaders have also attended the University of Virginia, including the 28th President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson,[179] the 18th Speaker of the United States House of Representatives Robert Mercer Taliaferro Hunter, U.S. Senator and 1968 Presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy[160] and his brother, U.S. Senator Ted Kennedy,[160] and former Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano.

Many of Virginia's governors studied at the university, including Democrats Gerald L. Baliles, Chuck Robb, John N. Dalton, Albertis S. Harrison, Jr., James Lindsay Almond, Jr., John S. Battle, Colgate Darden,[180] Elbert Lee Trinkle, Westmoreland Davis, Claude A. Swanson, Andrew Jackson Montague, and Frederick W. M. Holliday, and Republicans Jim Gilmore[160] and George Allen.[160]

(JD '51)

Former U.S. Senator and Attorney General

(BS '05)

Y Combinator partner and co-founder of reddit

(BA/BS '90)

Designer and TV host

(JD '56)

Former U.S. Senator

(JD '80)

President of the University of California, former politician

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 http://www.uvimco.com/home/showsubcategory?catID=145

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Current On-Grounds Enrollment". Retrieved 2014-09-15.

- ↑ "Usage Guidelines". The Graphic Identity for the University of Virginia. March 14, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ↑ http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/

- ↑ The Nobel Laureates are Woodrow Wilson, Alfred G. Gilman, Ferid Murad, Barry Marshall, Ronald Coase, James M. Buchanan, and William Faulkner.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 http://www.virginia.edu/factbook/uvafactbook2014.pdf

- ↑ Rhodes Scholarships by Instituation, retrieved August 28, 2014.

- ↑ Financing the University 101, retrieved August 31, 2014

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 "Cavalier Admissions Volunteer Handbook" (PDF). Office of Engagement, University of Virginia. 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ UVA Athletics Facts At a Glance, retrieved August 31, 2014

- ↑ Alf J. Mapp, Jr., Thomas Jefferson: Passionate Pilgrim, p. 19.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 New Englander and Yale Review, Volume 37, W. L. Kingsley, "Ought the State provide for Higher Education?", 1878, page 378.

- ↑ Phillips Russell, Jefferson, Champion of the Free Mind, p. 335.

- ↑ Circular of Information, State Board of Education, United States Bureau of Education. Washington (State) Superintendent of Public Instruction. Published by State Board of Education, 1888. p. 48.

- ↑ Higher Education in Transition: A History of American Colleges and Universities by John Seiler Brubacher, Willis Rudy. Published by Transaction Publishers, 1997. p. 148

- ↑ An Act to Establish A Normal School, 5 March 1888, accessed September 5, 2014

- ↑ Dabney, Virginius (1981). Mr. Jefferson's University: A History. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-8139-0904-X.

- ↑ Bruce, Philip Alexander (1920). History of the University of Virginia, vol. II. New York City: Macmillan.

- ↑ Popular Science, July 1905, "The Progress of Science"

- ↑ Joseph J. Ellis, American Sphinx, p. 283.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 1911 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 28, retrieved September 1, 2014

- ↑ "Edgar Allan Poe at the university". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ↑ Sampson, Zinie Chan (April 28, 2011). "Edgar Allan Poe's University of Virginia Room to Undergo Renovation". Huffington Post. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ↑ Civil War Casualties by the Civil War Trust, accessed September 5, 2014

- ↑ Charlottesville During the Civil War, accessed September 5, 2014

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 University of Virginia Alumni News, Volume II, Issue 7, page 74, December 10, 1913. Accessed September 5, 2014

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 See wikisource link to the right

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Encyclopedia Virginia President Edwin Alderman "By the turn of the 20th century the administrative affairs had grown to such an extent that the old form of government became too cumbersome. The appointment of Alderman brought a new era of progressivism to the university and service to Virginia." Retrieved 25 January 2012

- ↑ Popular Science, July 1905 Volume 67, "The Progress of Science"

- ↑ Bruce, Philip Alexander (1921). The History of the University of Virginia: The Lengthening Shadow of One Man V. New York: Macmillan. p. 61.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "The Road to Desegregation: Jackson, NAACP, and Swanson". Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 "Breaking and Making Tradition: Women at U VA". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ↑ Priya N. Parker (2004). "Storming the Gates of Knowledge: A Documentary History of Desegregation and Coeducation in Jefferson's Academical Village". Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ↑ University of Mary Washington: History and Development of the University.

- ↑ Historical Enrollment Data, accessed September 6, 2014

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 University braces for likely cuts in state funds, accessed September 8, 2014

- ↑ "Legislation". Restructuring Higher Education. University of Virginia. Retrieved 2008-05-22.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)". Restructuring Higher Education. University of Virginia. Retrieved 2008-05-22.

- ↑ de Vise, Daniel, "Teresa Sullivan Is First Female President to Lead University of Virginia" Washington Post, January 19, 2010.

- ↑ Rice, Andrew (September 11, 2012). "Anatomy of a Campus Coup". New York Times. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ↑ The Hook, a Charlottesville weekly, posted a series of articles detailing events as they occurred, collected at Hawes Spencer. "The Ousting of a President". The Hook. Retrieved 2014-11-13.(2012-13)

- ↑ Daily Progress Staff (June 14, 2012). "UVa Faculty Senate issues vote of no confidence in rector, Board of Visitors". The Daily Progress. Retrieved 2013-05-22.

- ↑ Karin Kapsidelis (June 15, 2012). "U.Va. Student Council seeks full explanation of ouster". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- ↑ Ted Strong (December 11, 2012). "UVa put on warning by accreditation group". The Daily Progress. Retrieved 2014-11-13.

- ↑ "Alumni Pledge Thousands in Donations Following Sullivan's Reinstatement". Newsplex.com. June 28, 2012. Retrieved 2013-05-22.

- ↑ Anita Kumar and Jenna Johnson (June 22, 2012). "McDonnell tells U-Va. board to resolve leadership crisis, or he will remove members". Washington Post. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ↑ Sara Hebel, Jack Stripling, and Robin Wilson (June 26, 2012). "U. of Virginia Board Votes to Reinstate Sullivan". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ↑ Board to Vote on Rector Removal Clause, accessed September 8, 2014

- ↑ Botelho, Greg (5 December 2014). "Rolling Stone apologizes over account of UVA gang rape". CNN. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ↑ T. Rees Shapiro (December 5, 2014). "Key elements of Rolling Stone's U-Va. gang rape allegations in doubt". Washington Post. Retrieved 2014-12-06.

- ↑ Nick Anderson (January 7, 2015). "New safety rules announced for University of Virginia fraternity parties". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ↑ Somaiya, Ravi (April 5, 2015). "Rolling Stone Retracts Article on Rape at University of Virginia". www.nytimes.com (New York Times). Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ↑ A Rape on Campus: What Went Wrong, accessed April 8, 2015

- ↑ Architectural Record," 4 (January–March 1895), pp. 351–353

- ↑ AIA Journal, 65 (July 1976), p. 91

- ↑ Keith Weimer. "Grizzard, Frank E.Documentary history of the construction of the buildings at the University of Virginia, 1817–1828. University of Virginia Libraries. 1996–2002.". Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ↑ ""America's most beautiful college campuses" Travel+Leisure (September 2011)". Travel + Leisure. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ↑ "Most beautiful universities". MSN.

- ↑ "Electronic Center at UVa Library". Digital Scholarship Services. Retrieved 2006-12-20.

- ↑ Lim, Melinda (2006-09-29). "Grad student discovers unpublished Frost poem". Cavalier Daily. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- ↑ "Clark Hall Named to Virginia Landmarks Registry," UVa Today, July 10, 2008

- ↑ "College Dean Search and Diversity Report Main Focus of Senate Meeting". University of Virginia. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- ↑ Jefferson's Legacy: Dialogues with the Past, accessed September 5, 2014

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Jeffersonian Quest, accessed September 5, 2014

- ↑ Going South: But where's the Lawn?, accessed September 9, 2014

- ↑ UVa Foundation sells five Kluge farms, accessed September 5, 2014

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 University to further develop Morven Farms, accessed September 5, 2014

- ↑ Virginia Route Index PDF (239 KB), revised July 1, 2003

- ↑ McCormick Road Dorms to See Massive Renovation Project, accessed September 8, 2014

- ↑ UVA Housing: Lawn, accessed September 5, 2014

- ↑ U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2013 Endowment Market Value PDF

- ↑ Kate Colwel (August 23, 2012). "Campaign Moves Past Difficulties". Cavalier Daily. Retrieved 2013-06-24.

- ↑ Wiley, Kevin (January 5, 2012). "Oversized Check from Reality". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved 2013-06-25.

- ↑ Lee Gardner (May 21, 2013). "U. of Virginia Raises $3 Billion". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 2013-06-24.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 75.3 Financing the University 101, accessed December 14, 2014

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 76.2 76.3 U-Va. should break some ties with state, panel says in preliminary report, accessed September 8, 2014

- ↑ U.Va. poised to issue $300 million in bonds to finance campus construction projects – Richmond Times-Dispatch

- ↑ Rector and Visitors of The University of Virginia (1995). "Chapter 4: University Regulations: Honorary Degrees". Rector and Visitors of The University of Virginia. Retrieved 2006-05-07. "The University of Virginia does not award honorary degrees. In conjunction with the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, the University presents the Thomas Jefferson Medal in Architecture and the Thomas Jefferson Award in Law each spring. The awards, recognizing excellence in two fields of interest to Jefferson, constitute the University's highest recognition of scholars outside the University."

- ↑ "No honorary degrees is an MIT tradition going back to ... Thomas Jefferson". MIT News Office. 2001-06-08. Retrieved 2006-05-07.:"MIT's founder, William Barton Rogers, regarded the practice of giving honorary degrees as 'literary almsgiving ... of spurious merit and noisy popularity ...' Rogers was a geologist from the University of Virginia who believed in Thomas Jefferson's policy barring honorary degrees at the university, which was founded in 1819."

- ↑ Andrews, Elizabeth; Murphy, Nora; Rosko, Tom. "William Barton Rogers: MIT's Visionary Founder". Exhibits: Institute Archives & Special Collections: MIT Libraries. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ↑ "Benefits of the Echols Scholars Program". University of Virginia. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- ↑ The Top American Research Universities, 2012 Annual Report, accessed December 14, 2014

- ↑ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2014-United States". ShanghaiRanking Consultancy. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ↑ "America's Top Colleges". Forbes.com LLC™. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ↑ "Best Colleges". U.S. News & World Report LP. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ↑ "About the Rankings". Washington Monthly. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ↑ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2014-United States". ShanghaiRanking Consultancy. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ↑ "University Rankings". Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- ↑ "World University Rankings". THE Education Ltd. Retrieved October 2, 2014.

- ↑ Best Law Schools, accessed September 2, 2014

- ↑ Best Business Schools, accessed September 2, 2014

- ↑ Best Medical Schools: Research, accessed September 2, 2014

- ↑ Full Time MBA Ranking, accessed September 3, 2014

- ↑ The Complete Ranking: Best Undergraduate Business Schools 2014, accessed September 2, 2014

- ↑ The Best 52 Colleges in America, Period, When You Consider Absolutely Everything That Matters, accessed September 6, 2014

- ↑ The Top 25 Colleges In The US, accessed September 22, 2014

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Avery, Christopher; Glickman, Mark E.; Hoxby, Caroline M; Metrick, Andrew (December 2005). "A Revealed Preference Ranking of U.S. Colleges and Universities, NBER Working Paper No. W10803". National Bureau of Economic Research. SSRN 601105.

- ↑ U.Va.'s Black Graduation Rate Remains No. 1 Nationally Among Public Universities Retrieved November 19, 2009

- ↑ U. Virginia's black grad rate tops among public universities Retrieved November 19, 2009

- ↑ University of Virginia Leads Public Universities with Highest African-American Graduation Rate for 12th Straight Year in 2006 Retrieved November 19, 2009

- ↑ Black Student Graduation Rates – Journal of Blacks in Higher Education Retrieved November 19, 2009

- ↑ "Comparing Black Enrollments at the Public Ivies. The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. 2005". Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 "U.Va. Unofficial Admissions Statistics, 2013-14". UVa Admissions Office. 2014-03-31. Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- ↑ "Online Applications Speed Admissions Process University Of Virginia Receives More Than 15,000 Applications, Extends Offers To 4,724 Students For Class Of 2008". University of Virginia News Office. 31 March 2004. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ Admissions Statistics| accessdate=4 September 2014

- ↑ Darden Class Profile, accessdate=4 September 2014

- ↑ AccessUVa Questions & Answers, retrieved September 4, 2014

- ↑ Best Values in Public Colleges, accessed September 8, 2014

- ↑ Princeton Review page on University of Virginia, accessed August 31, 2014

- ↑ The Daily News Record: Editorial Opinion

- ↑ "Princeton Review's 2009 Best Value Colleges".

- ↑ "Best Value Colleges for 2010 and how they were chosen". USA Today. 2010-01-12. Retrieved 2010-05-27.

- ↑ "Kiplinger's Best College Values". Kiplinger. March 2014.

- ↑ "America's 25 Hot Schools". Newsweek. August 2004.

- ↑ "Peace Corps – Top Producing Colleges and Universities" (PDF). Peace Corps. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- ↑ "Peace Corps – Top Producing Colleges and Universities" (PDF). Peace Corps. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ↑ "Society History". Karl Saur. Retrieved 2010-11-05.

- ↑ "High spirits: Wahoos tackle fourth-year fifth". Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- ↑ "Busch league: UVA gets big bucks to ban binging". Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- ↑ "Top 10 Party Schools". Playboy. Retrieved 2012-09-26.

- ↑ The Code of Honor, accessed December 15, 2014

- ↑ "The Honor Committee". University of Virginia. 2006-12-11. Retrieved 2007-01-09.

- ↑ Greta von Susteren (May 10, 2001). "University of Virginia Tackles Cheating Head On". CNN. Retrieved 2014-11-13.

- ↑ Meg Scheu (June 22, 1999). "Judge Denies Call to Dismiss Lawsuit". Cavalier Daily. Retrieved 2014-11-13.

- ↑ In 1983 the Fourth Circuit rejected a challenge brought by an expelled law student, the Henson case, concluding U VA's student-run honor system afforded sufficient due process to pass constitutional scrutiny.

- ↑ Robert O' Harrow Jr. (August 8, 1994). "Honor Case Causes Uproar at U-Va.; Some Angry Over Official Intervention, Student Panel's Unusual Reversal of Decision". Washington Post. Retrieved 2014-11-13.

- ↑ Borden, Jeremy (2008-04-27). "24,000-plus descend on Foxfield for annual steeplechase, social gathering". Daily Progress (Charlottesville).

- ↑ See the list of NCAA schools with the most championships: UNC has 40, UVA 22, Notre Dame 16, and Syracuse 13.

- ↑ Men's Basketball Final AP Poll 2013-14, accessed September 2, 2014

- ↑ College World Series official 2014 bracket, accessed September 2, 2014

- ↑ College Cup official 2013 bracket, accessed September 2, 2014

- ↑ Virginia wins 7th NCAA Championship in shootout versus UCLA, accessed December 14, 2014

- ↑ FSU tops Virginia for national title, accessed December 14, 2014

- ↑ Commonwealth Clash, accessed September 1, 2014

- ↑ Virginia, Virginia Tech announce "Commonwealth Clash", accessed September 12, 2014

- ↑ Commonwealth Challenge point system, accessed September 12, 2014

- ↑ Commonwealth Clash point system, accessed September 12, 2014

- ↑ Traditions – University of Virginia Cavaliers Official Athletic Site – VirginiaSports.com

- ↑ U.Va. Top News Daily

- ↑ "University of Virginia – virginia.edu". Alexa Internet, Inc. Retrieved 2007-01-09.

- ↑ Center For Politics website. Retrieved June 23, 2006.

- ↑ "Spanish Professor David T. Gies is Awarded One of Spain's Highest Honors". UVA Today. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ↑ "MONDAY: President Obama to Award 2011 National Medal of Arts and National Humanities Medal | The White House". Whitehouse.gov. 2012-02-10. Retrieved 2012-08-10.

- ↑ "Where Your Money Goes". Cavalier Daily. 2008-04-14.

- ↑ 145.0 145.1 145.2 145.3 U.Va. Darden School Survey Shows U.Va. Entrepreneurs' Significant Impact On Economy, accessed December 15, 2014

- ↑ Voice of His Generation, accessed September 13, 2014

- ↑

- Silverman, Kenneth (1991). Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-Ending Remembrance (Paperback ed.). New York: Harper Perennial. pp. 29–30. ISBN 0-06-092331-8.

- ↑ McCaw, Walter Drew (1904). Walter Reed: A Memoir. Walter Reed Memorial Association. p. 3.

- ↑ Eldredge, Charles C. (1993). Georgia O'Keeffe, American and modern. Yale University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-300-05581-8.

- ↑ Uchello, Marilyn; Barr (1992). Virginians All. Pelican Publishing Company. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-88289-853-7.

- ↑ Lohr, Steve (2007-03-20). "John W. Backus, 82, Fortran Developer, Dies". New York Times.

- ↑ Dr. J. Hartwell Harrison-Urologic Surgeon, The Boston Globe, January 21, 1984.

- ↑ "Astronaut Bio: Patrick G. Forrester". NASA Johnson Space Center. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

- ↑ "Astronaut Bio: Karl Gordon Henize". NASA Johnson Space Center. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

- ↑ "Astronaut Bio: Thomas H. Marshburn". NASA Johnson Space Center. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

- ↑ "Astronaut Bio: Leland D. Melvin". NASA Johnson Space Center. Retrieved 2014-11-05.

- ↑ "Bill Nelson (D-Fla.)". WhoRunsGov.com. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ↑ "Astronaut Bio: K. C.. Thornton". NASA Johnson Space Center. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

- ↑ "Astronaut Bio: Peter J.K. "Jeff" Wisoff". NASA Johnson Space Center. Retrieved 2014-11-05.

- ↑ 160.0 160.1 160.2 160.3 160.4 160.5 160.6 160.7 160.8 160.9 160.10 160.11 160.12 160.13 160.14 160.15 160.16 160.17 160.18 "U.Va. Notable Alumni". University of Virginia. Retrieved 2011-01-25.

- ↑ "Richard A. Lutz – Professor". Rutgers. Retrieved 2011-05-28.

- ↑ "Transcripts of a Troubled Mind". The Atlantic. 2004-04-29.

- ↑ "Radical Reconstruction" (PDF). Folio Weekly: 20. March 31 – April 6, 2009.

- ↑ "Barbara Perry". Miller Center of Public Affairs. Retrieved 2011-01-31.

- ↑ "Boyd Tinsley: Bio". The Official Dave Matthews Band Website. Archived from the original on 2007-02-08. Retrieved 2007-04-11.

- ↑ "The Unspoken Heard Speaks". 2004. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ↑ "Vern Yip: Overview". Creative Artists Agency Speakers. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ↑ Michael Shure - IMDb

- ↑ "Swarthmore Names Valerie Smith as New President," Swarthmore College website, http://www.swarthmore.edu/15th-president (accessed 21 February 2015).

- ↑ "Virgil profile". Online World of Wrestling. Retrieved 2009-11-14.

- ↑ Zillgitt, Jeff (2007-01-31). "A Cavalier get-together in Miami". USA Today.

- ↑ Dulac, Gerry (2009-01-30). "Tomlin earns respect". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 2011-01-31.

- ↑ "Devvarman Repeats as NCAA Singles Champion". VirginiaSports.com. 2008-05-27. Retrieved 2011-02-04.

- ↑ "Meola Will Rejoin The National Team". New York Times. 1999-01-06. Retrieved 2011-02-04.

- ↑ "Profiles of the U.S. Team". Washington Post. 1998-06-11. Retrieved 2011-02-04.

- ↑ Whiteside, Kelly (2006-06-02). "USA's Reyna Personifies Perseverance". USA Today. Retrieved 2011-02-04.

- ↑ "John Harkes". ESPN MediaZone. 2009-10-30. Retrieved 2011-02-04.

- ↑ "Clifton grad Nikki Krzysik tapped by U.S. team". NorthJersey.com. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ The World's Work: A History of our Time, Volume IV: November 1911-April 1912. Doubleday. 1912. pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Barbanel, Josh (1981-06-10). "Colgate W. Darden Jr. Dies". New York Times. pp. B6. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

Bibliography

- Abernethy, Thomas Perkins (1948). Historical Sketch of the University of Virginia. Richmond: Dietz Press.

- Addis, Cameron (2003). Jefferson's Vision for Education, 1760–1845. New York: Peter Lang Publishing. ISBN 0-8204-5755-8.

- Barker, David Michael (2000). "Thomas Jefferson and the Founding of the University of Virginia". Ph.D. diss. University of Illinois.

- Boyle, Sarah Patton (1962). The Desegregated Heart: A Virginian's Stand in a Time of Transition. New York: William Morrow & Company.

- Bruce, Philip Alexander (1920–22). History of the University of Virginia, 1819–1919: The Lengthening Shadow of One Man (5 vols ed.). New York: Macmillan.

- Dabney, Virginius (1981). Mr. Jefferson's University: A History. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0-8139-0904-X.

- Hein, David (2001). Noble Powell and the Episcopal Establishment in the Twentieth Century. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02643-8.[Chapter two covers student and faculty life at the University of Virginia in the 1920s, when Powell was de facto chaplain to the University.]

- Hitchcock, Susan Tyler (1999). The University of Virginia: A Pictorial History. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0-8139-1902-9.

- Mapp, Alf J. (1991). Thomas Jefferson: Passionate Pilgrim. Lanham, MD: Madison Books. ISBN 0-8191-8053-X.

- Waggoner, Jennings L. (2004). Jefferson and Education. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 1-882886-24-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to University of Virginia. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about University of Virginia. |

- Official website

- Official UVa athletics website

- Thomas Jefferson's Plan for the University of Virginia: Lessons from the Lawn - a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places lesson plan

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||