United Wireless Telegraph Company

The United Wireless Telegraph Company was the largest radio communications company in the United States, beginning with its late-1906 formation, until its bankruptcy and takeover by Marconi interests in mid-1912. Although at the time of its demise the company was operating around 70 land and 400 shipboard radiotelegraph installations — by far the most in the U.S. — the firm's management had showed substantially more interest in fraudulent stock promotion schemes than in ongoing operations or technical development. United Wireless' shutdown was hailed as eliminating one of the major financial frauds of the period, however, its disappearance also left the U.S. radio industry largely under foreign influence, dominated by the British-controlled American Marconi.

Formation

United Wireless' establishment was announced with great fanfare in November, 1906 by its founder and first president, notorious stock promoter Abraham White. Legally, the company was the reorganization of the Amalgamated Wireless Securities Company, which had been organized under the laws of Maine on December 6, 1904. Initially capitalized by 1,000,000 shares at $10 a share, par value, in February, 1907 the capitalization was increased to 2,000,000 shares at the par value, divided between 1,000,000 preferred and 1,000,000 common.

Abraham White had previously headed, beginning in 1902, a series of radio companies of dubious character, culminating in the American DeForest Wireless Telegraph Company. (United's head office was located at the old American DeForest headquarters at 42 Broadway, in New York City, and the company continued publication of the house organ The Aerogram.) The newly formed United was initially promoted as being a consolidation of the most prominent U.S. and British radio firms, combining American DeForest with the worldwide holding of London-based Marconi's Wireless Telegraph Company, Limited. The information about American DeForest was true, as United leased the older company's assets for $1, a maneuver that, not coincidentally, blocked American DeForest's creditors, most prominently Reginald Fessenden, from collecting on their legal judgments. However, the grand claims about gaining control of the Marconi companies were immediately and vigorously denounced by Marconi officials as "repugnant", and Wilson's overture to form an international company under his control was quickly and effectively repulsed.

Missing from the new company was the American DeForest Scientific Director, Lee DeForest, who had been forced out in the summer of 1906. DeForest's version of the events was that he resigned in protest over the improper actions of company management. However, an alternate explanation is that he was no longer welcome, due to his inability to develop an effective and non-infringing radio receiver — American DeForest's employment of electrolytic detectors had led to the Fessenden lawsuits, resulting in adverse and expensive legal judgments over the company's appropriation. Moreover, General H. H. C. Dunwoody, an American DeForest vice president, had recently invented a non-infringing carborundum detector, which made the services of DeForest appear to be unneeded.

Wilson takeover

The new company had a tumultuous start. In addition to the Marconi rebuff, in February, 1907, just two months after its founding, control of the company was quietly obtained by a group of self-proclaimed "reformers", led by stock promoter Colonel Christopher Columbus Wilson, the president of the International Loan & Banking Company of Denver, Colorado. Wilson, who had previously promoted American DeForest stock, forced White out to become the new company president, with Wilson's nephew, W. A. Diboll installed as company treasurer.

Business practices

In 1907, the radio industry had been developing for ten years, however, it had consistently lost money, for although the idea of wireless communication fired the imagination, there had been greater than expected difficulties in perfecting the technology to become commercially profitable. On land, radiotelegraph stations were not yet able to effectively compete with the existing network of landline telegraphs, and wireless telephony was still in the experimental stages. The main revenue source for the new communications technology was point-to-point radiotelegraph communication at sea, where the regular telegraph couldn't run, plus transoceanic transmissions, however, revenues from these sources were still very limited.

Because of the lack of legitimate opportunities, United was instead designed to prey upon the hopes (or greed) of investors who remembered the tremendous wealth that had been generated for early investors by the introduction of the telegraph and telephone. In addition, United Wireless promotional materials painted a glowing picture of the company's future, including claims that their engineers would soon perfect the wireless telephone, bringing income from subscribers listening to entertainment broadcasts, or using the device for personal communication. However, in truth, the limited engineering talents of the United staff never got much beyond the basic spark-gap radiotelegraph systems common to the industry of the day.

American DeForest stockholders were offered the chance to exchange their now essentially worthless holdings for United stock, in a series of complicated and confusing financial transactions that somehow were always to the advantage of the insiders at the expense of the regular shareholders. One unusual feature of the stock transfer offers was that the number of shares to be received was based on the amount of money originally paid for the stock, and not on the number of shares held. This was designed to penalize those who had made purchases on the open market at pennies-on-the-dollar, instead of paying the full price for purchases through the regular sales staff.

United management continued to offer new shares at inflated prices to the unwary, at the same time enforcing restrictions designed to artificially boost the stock price. A common practice was to include a clause that blocked the resale of the purchased stock on the open market, by refusing to register shares that had been transferred. These restrictions meant that United's management could declare arbitrary revaluations that increased at regular intervals, eventually reaching $50, allowing the company to claim fictitious appreciation that was never tested on the open market.

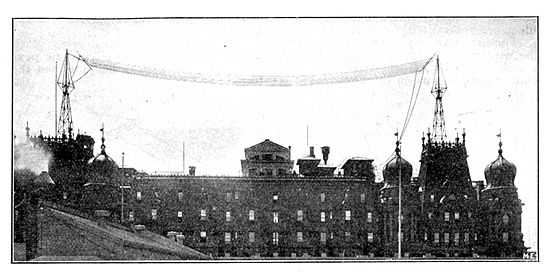

Because the primary objective of United Wireless was the sale of nearly worthless stock at inflated prices, day-to-day operations could be used as a "loss leader" for gaining publicity, and also for driving legitimate competitors out of business by starving them of revenue. Shipboard installations were provided at nominal rental cost or even for free, with the equipment and the radiotelegraph operators provided by United. While somewhat crude by industry standards, the United equipment was efficient enough to provide adequate service for its main clientele of coastwise shipping along the United States, as United, starting with its base along the Gulf and Atlantic Coasts, expanded to dominate the Pacific coast and Great Lakes, absorbing a series of smaller firms in the process. Also, by providing radio equipment to freighters and small passenger vessels which normally could not afford it, United's equipment did save the lives of seafarers who were now able to summon help when in distress.

Legal troubles

Following years of complaints, in June, 1910 inspectors from the United States Postal Department finally moved to shut down what was described as "one of the most gigantic schemes to defraud investors that has ever been unearthed in this country", beginning with the arrest of Christopher Columbus Wilson and one of his top associates. In August, seven United officials were formally indicted in Federal court — in response, the 64-year-old Wilson, a widower, blithely married his 18-year old secretary.[1] A trial followed the next year, and that May five United officials, including Wilson, were convicted of mail fraud, receiving sentences ranging from one to three years. (Wilson would die in prison, at the Atlanta, Georgia penitentiary, in August, 1912.)

Crippled by the prosecution of its upper management, United declared bankruptcy and went into receivership in July, 1911. It faced a second crisis when it was sued by the Marconi company for patent infringement. The case came to court in March, 1912 and was quickly won by Marconi when the defendants said they had no defense, resulting in a judgment in favor of the plaintiffs. After a short period of negotiation, United's assets were exchanged for 140,000 shares of British Marconi, worth about $1.1 million, meaning that the United stockholders received about $2 per share for their holdings. United's physical assets were then transferred from the parent Marconi company to American Marconi.

Thus, Abraham White's original dream of consolidating the largest U.S. radio company with the Marconi operations had finally been achieved, although under very different circumstances than White had envisioned. American Marconi, previously a minor factor in the U.S. market, now dominated its few remaining competitors. However, despite its American charter, the company was seen as controlled by its British counterpart, so in 1919, pressured by the United States Navy, American Marconi would sell its assets to General Electric, which used them to form the Radio Corporation of America, creating a new dominant American radio company.

Legacy

Overall, United Wireless' six-year dominance of U.S. radio communications had a strong negative impact, in part due to the skepticism and disrepute it and other fraudulent U.S. companies brought to the fledging industry. (Two other major fraudulent firms prosecuted in 1912 were the Radio Telephone Company and the Continental Wireless Company). Not all the reviews of the United era were completely negative — Lee DeForest, in his 1950 autobiography, while decrying the excesses of the company's senior management, did have good things to say about some of the technical staff, writing: "Charles Galbraith and his corps of honest, capable, hard-working men, engineers, and operators who had been instrumental in building up the American De Forest Wireless Telegraph Company, had gone determinedly ahead developing 'United' along sane and businesslike lines." However, a more common opinion about the most prominent U.S. radio firms of this era appeared in the December, 1907 issue of World's Work magazine: "The very word 'wireless' brings a smile to the lips of the Wall Street man... The time may come when the wireless will become suitable for consideration by investors. It will not come until some strong, clean, honest financial interests take charge and utterly eliminate the miserable, fraudulent, unwholesome methods that have marked the whole market history of these issues." John Bottomly, General Manager of American Marconi, assigned the job of incorporating United's assets into the Marconi operations, found the job challenging, reporting that: "A spirit of carelessness seems to have run through the whole conduct of [United] which is almost unparalleled in business history."

Footnotes

- ↑ WIRELESS MAN WEDS DAY HE'S INDICTED; President Wilson of the United, Accused of Fraud at 64, Makes Secretary of 18 His Bride.New York Times, August 4, 1910. Page 1.

References

- This article incorporates material from the Citizendium article "United Wireless Telegraph Company", which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License but not under the GFDL.

- Douglass, Susan J., Inventing American Broadcasting: 1899–1922, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland, 1987.

- MacLaurin, W. Rupert, Invention and Innovation in the Radio Industry, The MacMillan Company, New York, 1949.

External links

- Fayant, Frank, "Fools and Their Money/The Wireless Telegraph Bubble", Success magazine, January, 1907 – July, 1907 issues.

- Howeth, Captain L. S., History of Communications-Electronics in the United States Navy, Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1963.