United States presidential election, 1856

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Presidential election results map. Blue denotes states won by Buchanan/Breckinridge, Red denotes those won by Frémont & Dayton, and Grey denotes those won by Fillmore & Donelson. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

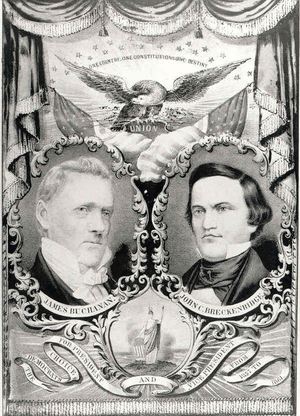

The United States presidential election of 1856 was the 18th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 4, 1856. Incumbent president Franklin Pierce was defeated in his effort to be re-nominated by the Democratic Party. James Buchanan, an experienced politician who had held a variety of political offices, was serving as the United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom and won the nomination instead.

Slavery was the omnipresent issue, and the Whig Party, which had since the 1830s been one of the two major parties in the U.S., had disintegrated. New parties such as the Republican Party (strongly against slavery's expansion) and American, or "Know-Nothing," Party (which ignored slavery and instead emphasized anti-immigration and anti-Catholic policies), competed to replace it as the principal opposition to the Democratic Party.[2] The Republican Party nominated John C. Frémont of California as its first presidential candidate. The Know-Nothing Party nominated former President Millard Fillmore, of New York.

Frémont condemned the Kansas–Nebraska Act, and decried the expansion of slavery. Buchanan warned that the Republicans were extremists whose victory would lead to civil war. The Democrats endorsed popular sovereignty as the method to determine slavery’s legality for newly admitted states. Buchanan won a plurality of the popular vote, but a majority of the electoral, and defeated Fillmore and Frémont, with the latter receiving fewer than 1200 popular votes in the slave states, with all of these coming from the Northern ones. The results in the Electoral College indicated that the Republican Party could possibly win the next presidential election by capturing only two more states.

Nominations

The 1856 presidential election was primarily waged among three political parties, several other parties had been active in the spring of the year fused with the major ones and disappeared forever. The conventions of these parties are considered below:

Democratic Party nomination

The Democratic Party was wounded from its devastating losses in the 1854–1855 midterm elections. U.S. Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, who had sponsored the Kansas-Nebraska Act, entered the race in opposition to President Franklin Pierce. The Pennsylvania delegation continued to sponsor its favorite son, James Buchanan.

The 7th Democratic National Convention was held in Smith and Nixon's Hall in Cincinnati, Ohio, on June 2 to 6, 1856. The delegates were deeply divided over slavery. For the first time in American history, a man who had been elected president was denied re-nomination after seeking it. On the first ballot, Buchanan placed first with 135.5 votes to 122.5 for Pierce, 33 for Douglas, and 5 for Lewis Cass. With each succeeding ballot, Douglas gained at Pierce's expense. On the 15th ballot, most of Pierce's delegates shifted to Douglas in an attempt to stop Buchanan, but Douglas withdrew when it became clear Buchanan had the support of the majority of those at the convention, also fearing that his continued participation might lead to divisions within the party that could endanger its chances in the general election.

A host of candidates were nominated for the Vice Presidency, but a number of them attempted to withdraw themselves from consideration, among them the eventual nominee, John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky. Breckinridge, besides having been selected as an elector, was also supporting Linn Boyd for the nomination. However, following a draft effort lead by the delegation from Vermont, Breckinridge was nominated on the second ballot.

The Anti-Slavery Coalition

North American Party nomination

The anti-slavery "Americans" from the North formed their own party after the nomination of Fillmore in Philadelphia. This party called for its national convention to be held in New York, New York, just before the Republican National Convention. Party leaders hoped to nominate a joint ticket with the Republicans to defeat Buchanan. The national convention was held on June 12 to 20, 1856 in New York. As John C. Frémont was the favorite to attain the Republican nomination there was a considerable desire for the North American party to nominate him, but it was feared that in doing so they may possibly injure his chances to actually become the Republican nominee. The delegates voted repeatedly on a nominee for president without a result. Nathaniel P. Banks was nominated for president on the 10th ballot over John C. Frémont and John McLean, with the understanding that he would withdraw from the race and endorse John C. Frémont once he had won the Republican nomination. The delegates, preparing to return home, unanimously nominated Frémont on the 11th ballot shortly after his nomination by the Republican Party in Philadelphia. The chairman of the convention, William F. Johnston, had been nominated to run for vice-president, but later withdrew when the North Americans and the Republicans failed to find an acceptable accommodation between him and the Republican nominee, William Dayton.[3]

Republican Party nomination

The Republican Party was formed in early 1854 to oppose the Kansas-Nebraska Act. During the midterm elections of 1854–1855, the Republican Party was one of the patchwork of anti-administration parties contesting the election. Overall, the Republicans won only 13 seats in the House of Representatives for the 34th Congress. However, the party collaborated with other disaffected groups and gradually absorbed them. In the elections of 1855, the Republican Party won three governorships.

The first Republican National Convention was held in the Musical Fund Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on June 17 to 19, 1856. The convention approved an anti-slavery platform that called for congressional sovereignty in the territories, an end to polygamy in Mormon settlements, and federal assistance for a transcontinental railroad. John C. Frémont, John McLean, William Seward, Salmon Chase, and Charles Sumner all were considered by those at the convention, but the latter three requested that their names be withdrawn. McLean's name was initially withdrawn by his manager Rufus Spalding, but the withdrawal was rescinded at the strong behest of the Pennsylvania delegation lead by Thaddeus Stevens.[4] Frémont was nominated for president overwhelmingly on the formal ballot, and William L. Dayton was nominated for vice-president over Abraham Lincoln.

the Whig/Know Nothing coalition

American Party nomination

The American Party, formerly the Native American Party, was the vehicle of the Know Nothing movement. The American Party absorbed most of the former Whig Party in 1854, and by 1855 it had established itself as the chief opposition party to the Democrats. In the 82 races for the House of Representatives in 1854, the American Party ran 76 candidates, 35 of whom won. None of the six Independents or Whigs who ran in these races was elected. The party then succeeded in electing Nathaniel P. Banks as Speaker of the House in the 34th Congress.

The American National Convention was held in National Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on February 22 to 25, 1856. Following the decision by party leaders in 1855 not to press the slavery issue, the convention had to decide how to deal with the Ohio chapter of the party, which was vocally anti-slavery. The convention closed the Ohio chapter and re-opened it under more moderate leadership. Delegates from Ohio, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Iowa, New England, and other northern states bolted when a resolution declaring that no candidate that was not in favor of prohibiting slavery north of the 36'30' parallel would be granted the nomination was voted down.[5] This removed a greater part of the American Party's support in the North outside of New York, where the conservative faction of the Whig Party remained faithful.[6] Former President Millard Fillmore was nominated for president with 179 votes out of the 234 votes cast. The convention chose Andrew Jackson Donelson of Tennessee for vice-president with 181 votes to 30 scattered votes and 24 abstentions.

Whig Party nomination

The Whig Party was reeling from electoral losses since 1852. Half of its leaders in the South bolted to the Southern Democratic Party, whereas in the North the Whig Party was moribund. This party remained somewhat alive in states like New York and Pennsylvania by joining the anti-slavery movement.

The fifth (and last) Whig National Convention was held in the Hall of the Maryland Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, on September 17 and 18, 1856. There were 150 delegates sent from 26 states. Though the leaders of this party wanted to keep the Whig Party alive, they doomed it by deciding to endorse the American Party's national ticket of Fillmore and Donelson. The 150 Whig delegates did so unanimously.

North American Seceders rump nomination

A group of North American delegates called the North American Seceders withdrew from the convention and met separately. They objected to the attempt to work with the Republican Party. The Seceders held their own national convention on 6/16-17/1856. 19 delegates unanimously nominated Robert F. Stockton for president and Kenneth Raynor for vice-president. The Seceders' ticket later withdrew from the contest, with Stockton endorsing Millard Fillmore for the Presidency.[7]

General election

Campaign

None of the three candidates took to the stump. The Republican Party opposed the extension of slavery into the territories — in fact, its slogan was "Free speech, free press, free soil, free men, Frémont and victory!" The Republicans thus crusaded against the Slave Power, warning it was destroying republican values. Democrats counter-crusaded by warning that a Republican victory would bring a civil war.

The Republican platform opposed the repeal of the Missouri Compromise through the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which enacted the policy of popular sovereignty, allowing settlers to decide whether a new state would enter the Union as free or slave. The Republicans also accused the Pierce administration of allowing a fraudulent territorial government to be imposed upon the citizens of the Kansas Territory, thus engendering the violence that had raged in Bleeding Kansas. They advocated the immediate admittance of Kansas as a free state. Along with opposing the spread of slavery into the continental territories of the United States, the party also opposed the Ostend Manifesto, which advocated the annexation of Cuba from Spain. In sum, the campaign's true focus was against the system of slavery, which they felt was destroying the Republican values that the Union had been founded upon.

The Democratic platform supported the Kansas-Nebraska Act and popular sovereignty. The party supported the pro-slavery territorial legislature elected in Kansas, opposed the free-state elements within Kansas, and castigated the Topeka Constitution as an illegal document written during an illegal convention. The Democrats also supported the plan to annex Cuba, advocated in the Ostend Manifesto, which Buchanan helped devise while serving as minister to Britain. The most influential aspect of the Democratic campaign was a warning that a Republican victory would lead to the secession of numerous southern states.

Because Fillmore was considered by many incapable of securing the Presidency on the American ticket, Whigs were urged to support Buchanan. Members of the Democratic party also called on nativists to make common cause with them against the specter of sectionalism, despite having previously attacked their political views. Fillmore and the Americans meanwhile insisted that they were the only "national party", with the Democrats leaning in favor of the South, and the Republicans fanatically in favor of the North and abolition.[8]

A minor scandal erupted when the Americans, seeking to turn the national dialogue back in the direction of nativism, put out a rumor that Frémont was in fact a Roman Catholic. The Democrats ran with it, and the Republicans found themselves unable to act effectively given that, while the statements were false, any stern message against those assertions might have crippled their efforts to attain the votes of German Catholics. Attempts were made to refute it through friends and colleagues, but the issue persisted throughout the campaign, and might have cost Frémont the support of a number of American Party members.[8]

The campaign had a different nature in the free states and the slave states. In the free states, there was a three-way campaign, which Frémont won with 45.2% of the vote to 41.5% for Buchanan and 13.3% for Fillmore; Frémont received 114 electoral votes to 62 for Buchanan. In the slave states, however, the contest was for all intents and purposes between Buchanan and Fillmore; Buchanan won 56.1% of the vote to 43.8% for Fillmore and 0.1% for Fremont, receiving 112 electoral votes to 8 for Fillmore. Nationwide, Buchanan won 174 electoral votes, a majority, and was thus elected. Frémont received no votes in 10 of the 14 slave states with a popular vote; he got 306 in Delaware, 285 in Maryland, 283 in Virginia, and 314 in Kentucky.

Of the 1,713 counties making returns, Buchanan won 1,083 (63.22%), Frémont won 366 (21.37%), and Fillmore won 263 (15.35%). One county (0.06%) in Georgia split evenly between Buchanan and Fillmore.

Results

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote(a) | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Pct | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Elect. vote | ||||

| James Buchanan | Democratic | Pennsylvania | 1,836,072 | 45.3% | 174 | John C. Breckinridge | Kentucky | 174 |

| John C. Frémont | Republican | California | 1,342,345 | 33.1% | 114 | William L. Dayton | New Jersey | 114 |

| Millard Fillmore | American/Whig | New York | 873,053 | 21.6% | 8 | Andrew Jackson Donelson | Tennessee | 8 |

| Other | 3,177 | 0.1% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 4,054,647 | 100% | 296 | 296 | ||||

| Needed to win | 149 | 149 | ||||||

Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. 1856 Presidential Election Results. Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections (July 27, 2005). Source (Electoral Vote): Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996. Official website of the National Archives. (July 31, 2005).

(a) The popular vote figures exclude South Carolina where the Electors were chosen by the state legislature rather than by popular vote.

-

Results by county explicitly indicating the percentage for the Democratic candidate.

-

Results by county explicitly indicating the percentage for the Republican candidate.

-

Results by county explicitly indicating the percentage for the Know Nothing candidate.

Results by state

| James Buchanan Democratic |

John C. Fremont Republican |

Millard Fillmore American / Whig |

State Total | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | |||||

| style"text-align:left" | Alabama | 9 | 46,739 | 62.08 | 9 | no ballots | 28,552 | 37.92 | - | 75,291 | AL | ||||||

| style"text-align:left" | Arkansas | 4 | 21,910 | 67.12 | 4 | no ballots | 10,732 | 32.88 | - | 32,642 | AR | ||||||

| style"text-align:left" | California | 4 | 53,342 | 48.38 | 4 | 20,704 | 18.78 | - | 36,195 | 32.83 | - | 110,241 | CA | ||||

| style"text-align:left" | Connecticut | 6 | 34,997 | 43.57 | - | 42,717 | 53.18 | 6 | 2,615 | 3.26 | - | 80,329 | CT | ||||

| style"text-align:left" | Delaware | 3 | 8,004 | 54.83 | 3 | 310 | 2.12 | - | 6,275 | 42.99 | - | 14,589 | DE | ||||

| style"text-align:left" | Florida | 3 | 6,358 | 56.81 | 3 | no ballots | 4,833 | 43.19 | - | 11,191 | FL | ||||||

| style"text-align:left" | Georgia | 10 | 56,581 | 57.14 | 10 | no ballots | 42,439 | 42.86 | - | 99,020 | GA | ||||||

| style"text-align:left" | Illinois | 11 | 105,528 | 44.09 | 11 | 96,275 | 40.23 | - | 37,531 | 15.68 | - | 239,334 | IL | ||||

| style"text-align:left" | Indiana | 13 | 118,670 | 50.41 | 13 | 94,375 | 40.09 | - | 22,386 | 9.51 | - | 235,431 | IN | ||||

| style"text-align:left" | Iowa | 4 | 37,568 | 40.70 | - | 45,073 | 48.83 | 4 | 9,669 | 10.47 | - | 92,310 | IA | ||||

| style"text-align:left" | Kentucky | 12 | 74,642 | 52.54 | 12 | no ballots | 67,416 | 47.46 | - | 142,058 | KY | ||||||

| style"text-align:left" | Louisiana | 6 | 22,164 | 51.70 | 6 | no ballots | 20,709 | 48.30 | - | 42,873 | LA | ||||||

| style"text-align:left" | Maine | 8 | 39,140 | 35.68 | - | 67,279 | 61.34 | 8 | 3,270 | 2.98 | - | 109,689 | ME | ||||

| style"text-align:left" | Maryland | 8 | 39,123 | 45.04 | - | 285 | 0.33 | - | 47,452 | 54.63 | 8 | 86,860 | MD | ||||

| style"text-align:left" | Massachusetts | 13 | 39,244 | 23.08 | - | 108,172 | 63.61 | 13 | 19,626 | 11.54 | - | 170,048 | MA | ||||

| style"text-align:left" | Michigan | 6 | 52,139 | 41.52 | - | 71,762 | 57.15 | 6 | 1,660 | 1.32 | - | 125,561 | MI | ||||

| style"text-align:left" | Mississippi | 7 | 35,456 | 59.44 | 7 | no ballots | 24,191 | 40.56 | - | 59,647 | MS | ||||||

| style"text-align:left" | Missouri | 9 | 57,964 | 54.43 | 9 | no ballots | 48,522 | 45.57 | - | 106,486 | MO | ||||||

| style"text-align:left" | New Hampshire | 5 | 31,891 | 45.71 | - | 37,473 | 53.71 | 5 | 410 | 0.59 | - | 69,774 | NH | ||||

| style"text-align:left" | New Jersey | 7 | 46,943 | 47.23 | 7 | 28,338 | 28.51 | - | 24,115 | 24.26 | - | 99,396 | NJ | ||||

| style"text-align:left" | New York | 35 | 195,878 | 32.84 | - | 276,004 | 46.27 | 35 | 124,604 | 20.89 | - | 596,486 | NY | ||||

| style"text-align:left" | North Carolina | 10 | 48,243 | 56.78 | 10 | no ballots | 36,720 | 43.22 | - | 84,963 | NC | ||||||

| style"text-align:left" | Ohio | 23 | 170,874 | 44.21 | - | 187,497 | 48.51 | 23 | 28,126 | 7.28 | - | 386,497 | OH | ||||

| style"text-align:left" | Pennsylvania | 27 | 230,686 | 50.13 | 27 | 147,286 | 32.01 | - | 82,189 | 17.86 | - | 460,161 | PA | ||||

| style"text-align:left" | Rhode Island | 4 | 6,680 | 33.70 | - | 11,467 | 57.85 | 4 | 1,675 | 8.45 | - | 19,822 | RI | ||||

| style"text-align:left" | South Carolina | 8 | no popular vote | 8 | no popular vote | no popular vote | - | SC | |||||||||

| style"text-align:left" | Tennessee | 12 | 69,704 | 52.18 | 12 | no ballots | 63,878 | 47.82 | - | 133,582 | TN | ||||||

| style"text-align:left" | Texas | 4 | 31,169 | 66.59 | 4 | no ballots | 15,639 | 33.41 | - | 46,808 | TX | ||||||

| style"text-align:left" | Vermont | 5 | 10,577 | 20.84 | - | 39,561 | 77.96 | 5 | 545 | 1.07 | - | 50,748 | VT | ||||

| style"text-align:left" | Virginia | 15 | 90,083 | 59.96 | 15 | no ballots | 60,150 | 40.04 | - | 150,223 | VA | ||||||

| style"text-align:left" | Wisconsin | 5 | 52,843 | 44.22 | - | 66,090 | 55.30 | 5 | 579 | 0.48 | - | 119,512 | WI | ||||

| TOTALS: | 296 | 1,835,140 | 45.29 | 174 | 1,340,668 | 33.09 | 114 | 872,703 | 21.54 | 8 | 4,051,605 | US | ||||

| TO WIN: | 149 | |||||||||||||||

See also

- Inauguration of James Buchanan

- Origins of the American Civil War

- Third Party System

- United States House of Representatives elections, 1856

- United States Senate elections, 1856

- American election campaigns in the 19th century

- History of the United States (1849–1865)

- History of the United States Democratic Party

- History of the United States Republican Party

References

- ↑ "Voter Turnout in Presidential Elections". The American Presidency Project. UC Santa Barbara.

- ↑ http://www.historycentral.com/elections/1856.html

- ↑ Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.. American Presidential Elections. pp. 1022–1023.

- ↑ Eugene H. Roseboom. A History of Presidential Elections. p. 162.

- ↑ Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.. American Presidential Elections. p. 1020.

- ↑ Eugene H. Roseboom. A History of Presidential Elections. p. 159.

- ↑ Eugene H. Roseboom. A History of Presidential Elections. p. 160.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Eugene H. Roseboom. A History of Presidential Elections. p. 166.

Further reading

- Anbinder, Tyler (1992). Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-508922-7.

- Foner, Eric (1970). Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gienapp, William E. (1987). The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852-1856. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504100-3.

- Holt, Michael F. (1978). The Political Crisis of the 1850s. New York: Norton. pp. 139–181. ISBN 0-393-95370-X.

- Nevins, Allan (1947). Ordeal of the Union: vol 2: A House Dividing, 1852-1857. New York. The most detailed narrative.

- Pierson, Michael D. (2002). "'Prairies on Fire': The Organization of the 1856 Mass Republican Rally in Beloit, Wisconsin". Civil War History 48. ISSN 0009-8078.

- Potter, David (1976). The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-090524-7.

- Rawley, James A. (1969). Race and Politics: "Bleeding Kansas" and the Coming of the Civil War. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

- Sewell, Richard H. (1976). Ballots for Freedom: Antislavery Politics in the United States, 1837-1860. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 254–291. ISBN 0-19-501997-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United States presidential election, 1856. |

- Presidential Election of 1856: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Nativism in the 1856 Presidential Election

- 1856 popular vote by counties

- 1856 state-by-state popular voting results

- James Buchanan and the Election of 1856

- How close was the 1856 election? — Michael Sheppard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- 1856 Republican Platform

- Election of 1856 in Counting the Votes

Navigation

| ||||||||||||||