Unitary operator

In functional analysis, a branch of mathematics, a unitary operator (not to be confused with a unity operator) is defined as follows:

Definition 1. A bounded linear operator U : H → H on a Hilbert space H is called a unitary operator if it satisfies U*U = UU* = I, where U* is the adjoint of U, and I : H → H is the identity operator.

The weaker condition U*U = I defines an isometry. The other condition, UU* = I, defines a coisometry. Thus a unitary operator is a bounded linear operator which is both an isometry and a coisometry.[1]

An equivalent definition is the following:

Definition 2. A bounded linear operator U : H → H on a Hilbert space H is called a unitary operator if:

- U is surjective, and

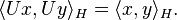

- U preserves the inner product of the Hilbert space, H. In other words, for all vectors x and y in H we have:

The following, seemingly weaker, definition is also equivalent:

Definition 3. A bounded linear operator U : H → H on a Hilbert space H is called a unitary operator if:

- the range of U is dense in H, and

- U preserves the inner product of the Hilbert space, H. In other words, for all vectors x and y in H we have:

To see that Definitions 1 & 3 are equivalent, notice that U preserving the inner product implies U is an isometry (thus, a bounded linear operator). The fact that U has dense range ensures it has a bounded inverse U−1. It is clear that U−1 = U*.

Thus, unitary operators are just automorphisms of Hilbert spaces, i.e., they preserve the structure (in this case, the linear space structure, the inner product, and hence the topology) of the space on which they act. The group of all unitary operators from a given Hilbert space H to itself is sometimes referred to as the Hilbert group of H, denoted Hilb(H).

A unitary element is a generalization of a unitary operator. In a unital *-algebra, an element U of the algebra is called a unitary element if U*U = UU* = I, where I is the identity element.[2]:55

Examples

- The identity function is trivially a unitary operator.

- Rotations in R2 are the simplest nontrivial example of unitary operators. Rotations do not change the length of a vector or the angle between two vectors. This example can be expanded to R3.

- On the vector space C of complex numbers, multiplication by a number of absolute value 1, that is, a number of the form eiθ for θ ∈ R, is a unitary operator. θ is referred to as a phase, and this multiplication is referred to as multiplication by a phase. Notice that the value of θ modulo 2π does not affect the result of the multiplication, and so the independent unitary operators on C are parametrized by a circle. The corresponding group, which, as a set, is the circle, is called U(1).

- More generally, unitary matrices are precisely the unitary operators on finite-dimensional Hilbert spaces, so the notion of a unitary operator is a generalization of the notion of a unitary matrix. Orthogonal matrices are the special case of unitary matrices in which all entries are real. They are the unitary operators on Rn.

- The bilateral shift on the sequence space ℓ2 indexed by the integers is unitary. In general, any operator in a Hilbert space which acts by shuffling around an orthonormal basis is unitary. In the finite dimensional case, such operators are the permutation matrices. The unilateral shift is an isometry; its conjugate is a coisometry.

- The Fourier operator is a unitary operator, i.e. the operator which performs the Fourier transform (with proper normalization). This follows from Parseval's theorem.

- Unitary operators are used in unitary representations.

Linearity

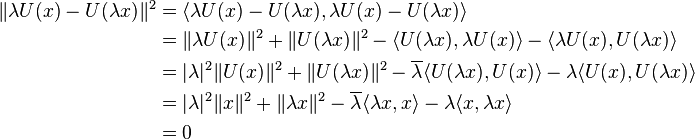

The linearity requirement in the definition of a unitary operator can be dropped without changing the meaning because it can be derived from linearity and positive-definiteness of the scalar product:

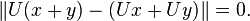

Analogously you obtain

Properties

- The spectrum of a unitary operator U lies on the unit circle. That is, for any complex number λ in the spectrum, one has |λ| = 1. This can be seen as a consequence of the spectral theorem for normal operators. By the theorem, U is unitarily equivalent to multiplication by a Borel-measurable f on L2(μ), for some finite measure space (X, μ). Now UU* = I implies |f(x)|2 = 1, μ-a.e. This shows that the essential range of f, therefore the spectrum of U, lies on the unit circle.

See also

- Unitary matrix

- Unitary transformation

- Antiunitary

Footnotes

- ↑ (Halmos 1982, Sect. 127, page 69)

- ↑ Doran, Robert S.; Victor A. Belfi (1986). Characterizations of C*-Algebras: The Gelfand-Naimark Theorems. New York: Marcel Dekker. ISBN 0-8247-7569-4.

References

- Lang, †‡‡∭ Serge (1972). Differential manifolds. Reading, Mass.–London–Don Mills, Ont.: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc.

- Halmos, Paul (1982). A Hilbert space problem book. Springer.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||