Unionism in Scotland

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Scotland |

|

|

Scotland in the UK

|

|

Scotland in the EU |

|

Administrative divisions

|

|

British politics portal |

Unionism in Scotland is a political movement that seeks to keep Scotland within the United Kingdom in its present structure as one of the countries of the United Kingdom. It is part of the wider British unionist movement and is closely linked to British nationalism and the notion of Britishness. There are many strands of political Unionism in Scotland, some of which have strong ties to Unionism and Loyalism in Northern Ireland. Unionism is a movement often categorised primarily as being in opposition to Scottish independence.

Ahead of a referendum on Scottish independence, the main unionist political parties in Scotland joined to form Better Together in support of Scotland remaining part of the United Kingdom.

The Union

The political union between the Kingdoms of Scotland and England (also including Wales as an English possession) was created by the Acts of Union, passed in the parliaments of both kingdoms in 1707 and 1706 respectively, which united the governments of what had previously been independent states (though they had shared the same monarch in a personal union since 1603) under the Parliament of Great Britain. The Union was brought into existence under the Acts of Union on the 1 May 1707.

With the Act of Union 1800, Ireland united with Great Britain into what then formed the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The history of the Unions is reflected in various stages of the Union Flag, which forms the flag of the United Kingdom. The larger part of Ireland left the United Kingdom in 1922, however the separation of Ireland which originally occurred under the Government of Ireland Act 1920 was upheld by the British Government and the Unionist-controlled devolved Parliament of Northern Ireland, and chose to remain within the state today, which is now officially termed the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The 300th anniversary of the union of Scotland and England was marked in 2007.

Status of the term

Unionism is the status quo in Scotland; it is not a single movement, and is not revolutionary. There are other uses of the term unionism in Scotland which, at least historically, took precedence. Amongst these is the name of the Unionist Party, which was the full title of the Tory party in Scotland before the organisation formally merged with the Conservative and Unionist Party in England and Wales in 1965, adopting the latter name. This party was often known simply as the Unionists. 'Unionist' in the names of these parties is rooted in the merger of the Conservative and Liberal Unionist Parties in 1912. The union referred to therein is the 1800 Act of Union, not the Acts of Union 1707.[1]

The term may also be used to suggest an affinity with Northern Irish unionism, rather than unionism in Scotland.

The former Secretary of State for Scotland, Michael Moore MP has written that he does not call himself a Unionist, despite being a supporter of the union. This he ascribes to the Liberal Democrat position in regard to Home Rule and decentralisation within the United Kingdom, noting that: 'for me the concept of "Unionism" does not capture the devolution journey on which we have travelled in recent years.' He suggests the connotations behind Unionism are of adherence to a constitutional status quo.[2]

Unionism and political parties

The three largest and most significant political parties that support unionism in Scotland are the Labour Party, the Liberal Democrats and the Conservative and Unionist Party, all of which organise and stand in elections across Great Britain. However, these three parties have differing beliefs about what Scotland's status should be, particularly in their support of devolution (historically Home Rule) or federalism.

The Conservatives, as a UK-wide party, fielded candidates in Scotland until the creation of a separate Unionist Party, which merged into the UK-wide Conservative Party in 1965. In 1968 the Declaration of Perth policy document committed the Conservatives to Scottish devolution in some form, and in 1970 the Conservative government published Scotland's Government, a document recommending the creation of a Scottish Assembly. Support for devolution within the party declined and was opposed by the Conservative government in the 1980s and 1990s, and remained opposed in the run up to the 1997 Scottish devolution referendum.[3] There is a small Scottish Unionist Party, which broke from the Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party in opposition to the Anglo-Irish Agreement It has no representation in either the UK or Scottish parliaments. Jacobitism, which took place across Britain, was supported from the outset by Tories in both England and Scotland, but became associated with Scottish nationalism, and was popularised as a key part of the Scottish national identity by the writings of Walter Scott, who was a unionist and a Tory.

The Labour Party has also had a mixed relationship with devolution. In 1950, it abandoned its previous support for Home Rule. Following the Kilbrandon Report in 1973 recommending a devolved Scottish Assembly, the Labour government of 1974-1979 introduced the Scotland Act 1978 to Parliament, which initiated a referendum on devolution. Failing to pass, the referendum was shelved. When the party returned to power in 1997, they introduced a devolution referendum which resulted in the enactment of the Scotland Act 1998 and the creation of the Scottish Parliament.[3]

The Scottish Liberal Democrats have previously been supportive of Home Rule as part of a wider belief in subsidiarity and localism.[4] The party is generally supportive of a federal relationship between the countries of the United Kingdom.[5]

Political opposition to unionism

Notable opponents of unionism in the Scottish Parliament are the Scottish National Party (SNP) who have formed the Scottish Government since 2007 and the Scottish Green Party.[6] The Scottish Socialist Party (SSP) and Solidarity seek a return to Scotland being a sovereign state and a republic, independent of England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Of these parties, only the SNP currently has representation in the UK Parliament, which it has had continuously since winning the Hamilton by-election, 1967. The SNP and the Scottish Greens both have representation within the Scottish Parliament.

The support of Solidarity and the SSP of an independent socialist Scotland has been criticised by the Communist Party of Great Britain as being unsocialist.[7]

Other support of unionism

In 2007, official celebrations of the 300th anniversary of the union of Scotland with England were muted, due to the proximity of the Scottish Parliamentary elections, which was two days after the date of the first meeting of the parliament of Great Britain on 1 May. The union has become a subject of great historical interest recently, with a number of books and television series being released. Surrounding January, the anniversary of the signing of the union treaty but not the actual incorporation, the issue was heavily covered by the media. A £2 coin marking the anniversary was distributed by the Royal Mint.

On 24 March 2007 the Grand Orange Lodge of Scotland, one body which has been vehement in its defence of the union, organised a march of 12,000 of its members through Edinburgh's Royal Mile to celebrate the 300th anniversary.[8] The high turnout was believed to be in part due to opposition to Scottish independence.[9] The Orange Order used the opportunity to speak out against the possibility of nationalists increasing their share of the vote in the 2007 Scottish Parliament election. However, the SNP secured a plurality and a minority government under Alex Salmond following the election.

In the run up to the Scottish Independence referendum, which threatened to see Scotland become its own sovereign state independent of the United Kingdom, the Orange Order held a Unionist march and rally in Edinburgh which involved 15,000 Orangemen, loyalist bands and no voters from across Scotland and the UK. This was followed by a Unity rally by the "Let's Stay Together Campaign" in London's Trafalgar Square where 5,000 English people gathered to urge Scotland to vote "No" to independence. Similar events were held in other cities across the rest of the United Kingdom including in Manchester, Belfast and Cardiff.[10][11][12][13]

Ties to Unionism in Northern Ireland

There is some degree of social and political co-operation between some Scottish unionists and Northern Irish unionists, due to their similar aims of maintaining the unity of their constituent country with the United Kingdom. For example, the Orange Order parades in Orange walks in Scotland and Northern Ireland. However, many unionists in Scotland shy away from connections to unionism in Northern Ireland in order not to endorse any side of a largely sectarian conflict. This brand of unionism is largely concentrated in the Central Belt and west of Scotland. Loyalists in Scotland are seen as a militant or extreme branch of unionism. Orangism in west and central Scotland, and opposition to it by Catholics in Scotland, can be explained as a result of the large amount of immigration from Northern Ireland.[14] A unionist rally was held in Belfast in response to the referendum on Scottish independence. Northern Irish unionists gathered to urge Scottish voters to remain within the United Kingdom.[10]

Demographics

.svg.png)

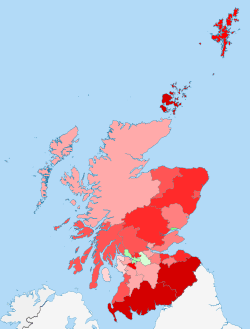

In the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, 55.3% of voters rejected independence in favour of remaining a part of the United Kingdom by comparison to 44.7% who voted for independence. Out of 32 council areas in Scotland, four favoured independence, these being: Glasgow (with 53.5% yes votes), Dundee (where 57.3% of people voted for independence), West Dunbartonshire (where 54% of people voted for independence) and North Lanarkshire (which had 51.1% Yes votes). Orkney, the Borders, Dumfries and Galloway and Shetland returned the largest % No votes at 67.2%, 66.56%, 65.67% and 63.71% respectively.

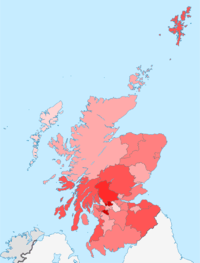

In the 2011 census 8% of people in Scotland identified themselves as "British only" and 18% described themselves as "Scottish and British only". Britishness was more prominent in areas which rejected independence by a large margin, with 26% of people from East Renfrewshire identifying themselves as "Scottish and British"; this was followed by East Dunbartonshire (25%), Renfrewshire (21%) and South Ayrshire (21%). 12% of people from Shetland and Argyll and Bute identified themselves "British only" - after this came the Borders, Orkney, Moray and Edinburgh where 11% of people called themselves "British only". The largest % of people who identified themselves as either "Scottish and British only" or "British only" was in East Dunbartonshire (34%) and East Renfrewshire (35%). Unionism in Orkney and Shetland has been seen as so severe that it was suggested prior to the referendum that should Scotland become independent then the isles themselves could secede from Scotland in favour of independence or political union with England, Wales and Northern Ireland as a British Overseas Territory (similar to the Isle of Man) however, like most of Scotland, the majority of people from the Northern Isles identified themselves as "Scottish only" in the 2011 census.[15] In Orkney, Shetland, the Borders, Dumfries and Galloway, Highland, Angus and Argyll and Bute over 7% of people identified themselves English, Welsh and/or Northern Irish.[16] When divided into Scottish Parliamentary constituencies, Britishness was most prominient in Eastwood (38.1%), Edinburgh Southern, Western and Central (where 35.4%, 32.3% and 31.1% of people identified themselves as British respectively), Strathkelvin and Bearsden(31.8%), Renfrewshire North and West (31.2%) and Ayr (30.2%).[17] Despite this, only Eastwood and Ayr elected an MSP from one of the Unionist political parties of Scotland - in Eastwood this was Labour MSP Ken Macintosh, Ayr's MSP is Conservative John Scott. Renfrewshire North and West rejected Independence by 55.7%.[18]

Religion could be seen as a contributing factor towards Unionism. Traditionally, Roman Catholic areas have been more sympathetic towards Irish unity and the break-up of the British state. Of the four council areas with the highest % Roman Catholic population, three voted in favour of independence - these being North Lanarkshire (35% Roman Catholic), West Dunbartonshire (33%) and Glasgow (27%). Inverclyde houses the largest proportion of Catholics in Scotland at 37% and narrowly rejected independence by a margin of 50.1% No to 49.9% Yes. South Ayrshire has the highest proportion of Christians who follow the Church of Scotland at 44% followed by Dumfries and Galloway where 43% of people are Church of Scotland Protestants. Both of these areas are often considered to be hard-line Unionist areas. Of the Conservative and Unionist Party's three constituency seats in the Scottish Parliament, two of them are found in South Ayrshire (Ayr) and Dumfries and Galloway (Galloway and West Dumfries). 42.7% of Ayr's population and 42.8% of Galloway and West Dumfries' are Church of Scotland Protestant. In the independence referendum, 57.9% of voters from South Ayrshire rejected independence.[19] Nationally, 6.77% of Church of Scotland Christians said they were "British only" and 24.79% said they were "Scottish and British only" whereas only 5.28% of Roman Catholics identified themselves as "British only" and 13.89% described themselves as "Scottish and British only".[20] Further to this, a Lord Ashcroft poll after the independence referendum suggests 70% of Protestants rejected independence whilst only 43% of Roman Catholics voted "No" in the referendum.[21]

Polling suggests that in January 2014, when forced to choose a single identity, 65% would describe themselves as "Scottish" whilst 23% would call themselves "British" – 2% identified themselves as "English". Over recent years, the figure for "Scottish" only has slowly declined after reaching a height of 80% in 2000 – the figure for 2014 has been the lowest for at least 15 years. The largest figure for choosing "British" was 24% in 2013, followed by the figure for 2014.[22] Almost a third of people described themselves as "Equally Scottish and British" whilst only a fourth described themselves as "Scottish not British" - at the same time 5% of people described themselves as "more British than Scottish" whilst 6% said they were "British not Scottish". This is the highest recorded level of British sentiment in Scotland since 1997 – trends suggest that the figure is slowly increasing across time.[23] A poll commissioned by ICM and the Guardian in December 2014 after the independence referendum found the largest level of British identity ever recorded in Scotland. When asked "Would you rather describe yourself as British or Scottish?" and given the choice of answering with "British", "Scottish" or "Other" as their national identity, 36% of respondents stated that they were "British" - a rise of 13% from January 2014. 58% of respondents state that they were "Scottish" - this is 7% lower than the figure in January 2014.[24]

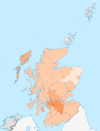

Support for the union is more prevalent among those in Social Grade ABC1 and those aged 65 and over. Support for independence is higher in Social Grade C2DE and among younger voters.[25]

List of unionist organisations in Scotland

The following is a list of active political parties and organisations in Scotland who support the union.

- Parties with parliament/local government seats

- Other parties

- Alliance for Workers Liberty

- Britain First[26]

- Britannica Party[27]

- British National Party (BNP)[28]

- Communist Party of Britain

- National Front (NF)[29]

- Respect Party[30]

- Scottish Unionist Party (SUP)

- UK Independence Party (UKIP)[31]

- Other groups

References

- ↑ "Cameron plans a clever game of cat and mouse on independence - Scotsman.com News". Edinburgh: News.scotsman.com. 2008-09-27. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ↑ "Michael Moore MP writes: I am not your average unionist". Libdemvoice.org. 2011-12-21. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2009/11/26155932/3

- ↑ "Microsoft Word - Steel Commission Report March 2006 formatted.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- ↑ "Scottish independence: Lib Dems push federal UK plans". 2012-10-17.

- ↑ "Scottish Green Party Manifesto 2007, pp24-25". Retrieved 2008-08-17.

- ↑

- ↑ "Scotland | Edinburgh and East | Orange warning over Union danger". BBC News. 2007-03-24. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ↑ "Edinburgh Evening News". Edinburghnews.scotsman.com. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Spiro, Zachary. "'Day of Unity' grassroots rallies across the UK". Daily Telegraph (Telegraph Media Group). Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ↑ Libby Brooks. "Orange Order anti-independence march a 'show of pro-union strength'". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ↑ "Orange Order descends on Edinburgh to protest against 'evil enemy' of nationalism ahead of Scottish independence vote". Mail Online. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ↑ "Orange Order march through Edinburgh to show loyalty to UK". Financial Times. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ↑ "10-bradley-pp237-261" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ↑ "Scottish independence: islands consider their own 'home rule'". 2013-03-17. Retrieved 2014-04-15.

- ↑ "National Identity". 2012. Retrieved 2014-10-18.

- ↑ "Find out about an area". 2011. Retrieved 2014-11-29.

- ↑ "RESULTS ANALYSIS" (PDF). 2014. Retrieved 2014-11-29.

- ↑ "Religion". 2012. Retrieved 2014-10-18.

- ↑ "Table DC2204SC - National identity by religion". 2011. Retrieved 2014-10-18.

- ↑ "How Scotland voted, and why". Lord Ashcroft. Lord Ashcroft. 19 September 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ↑ "'Forced choice' national identity". 2014. Retrieved 2014-10-18.

- ↑ "Scottish Social Attitudes". 2014. Retrieved 2014-10-18.

- ↑ "Would you rather describe yourself as British or Scottish?". 2014. Retrieved 2014-10-18.

- ↑ "Final Prediction" (PDF). 2014. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- ↑ Britain First official website. Statement of Principles. "Britain First is a movement of British Unionism. We support the continued unity of the United Kingdom whilst recognising the individual identity and culture of the peoples of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. We abhor and oppose all trends that threaten the integrity of the Union". Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ↑ Beaton, Connor (21 June 2014). "BNP splinter joins anti-indy campaign". The Targe. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ↑ "Why does Scotland matter?". British National Party. 27 July 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ↑ British National Front website. What we stand for. "We stand for the continuation of the UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND - Four Countries, One Nation. Scotland, Ulster, England and Wales, united under our Union Flag - we will never allow the traitors to destroy our GREAT BRITAIN!". Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ↑ "Scotland : The Respect Party – Peace, Justice & Equality". The Respect Party - Peace, Justice & Equality. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ↑ "Scottish independence: Nigel Farage to appear at UKIP pro-Union rally". BBC News. BBC. 31 August 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ↑ "Scottish independence: Orange Lodge registers to campaign for a 'No' vote". BBC News. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

See also

- Scottish Unionist Party

- Unionist Party (Scotland)

- Sectarianism in Glasgow

- Unionism in England

- Unionism in Wales

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||