Union for the Mediterranean

|

| |

| Formation | 13 July 2008 |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain |

Region served | Mediterranean |

Membership |

43 states

1 observer

|

Official language | Arabic, English, French, Spanish |

Secretary General | Fathallah Sijilmassi |

| Website | ufmsecretariat.org |

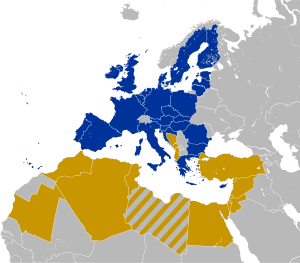

The Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) is a multilateral partnership of 43 countries from Europe and the Mediterranean Basin: the 28 member states of the European Union and 15 Mediterranean partner countries from North Africa, the Middle East and Southeast Europe. It was created in July 2008 as a relaunched Euro-Mediterranean Partnership (the Barcelona Process), when a plan to create an autonomous Mediterranean Union was dropped. The Union has the aim of promoting stability and prosperity throughout the Mediterranean region.

The Union for the Mediterranean introduced new institutions into the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership such as the Secretariat of the Union for the Mediterranean, established in Barcelona in 2010, with the aim to identify and promote regional cooperation projects that contribute to achieve its goals and objectives as indicated in its mandate.

The Union for the Mediterranean is the southern regional cooperation branch, which works in parallel to the European Neighbourhood Policy. Its eastern counterpart is the Eastern Partnership.

Membership

The members of the Union of the Mediterranean are the following:

- From the European Union side:

- The 28 European Union member states: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and United Kingdom.

- The European Commission.

- From the side of the Mediterranean Partner countries:

- 15 member states: Albania, Algeria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Mauritania, Monaco, Montenegro, Morocco, Palestinian Authority, Syria (self-suspended on 22 June 2011), Tunisia and Turkey.

- Libya as an observer state.[1] The UfM has expressed a desire to grant Libya full membership,[2] and Mohamed Abdelaziz, Libya's Foreign Minister, has stated that his country is "open" to joining.[3]

- The League of Arab States[4][5]

History

Antecedents: Barcelona Process

The Euro-Mediterranean Partnership, also known as the Barcelona Process, was created in 1995 as a result of the Conference of Euro-Mediterranean Ministers of Foreign Affairs held in Barcelona under the Spanish presidency of the EU. It culminates a series of attempts by European countries to articulate their relations with their North African and Middle Eastern neighbours: the global Mediterranean policy (1972–1992) and the renovated Mediterranean policy (1992–1995).[6]

Javier Solana opened the conference saying that they were brought together to straighten out the "clash of civilizations" and misunderstandings that there had been between them, and that it "was auspicious" that they had convened on the 900th anniversary of the First Crusade. He described the conference as a process to foster cultural and economic unity in the Mediterranean region. The Barcelona Treaty was drawn up by the 27 countries in attendance, and Solana, who represented Spain as their foreign minister during their turn at the Presidency of the Council of the European Union, was credited with the diplomatic accomplishment.

According to the 1995 Barcelona Declaration, the aim of the initiative was: "turning the Mediterranean basin into an area of dialogue, exchange and cooperation guaranteeing peace, stability and prosperity."[7] The Declaration established the three main objectives of the Partnership:

- Definition of a common area of peace and stability through the reinforcement of political and security dialogue (Political and Security Basket).

- Construction of a zone of shared prosperity through an economic and financial partnership and the gradual establishment of a free-trade area (Economic and Financial Basket).

- Rapprochement between peoples through a social, cultural and human partnership aimed at encouraging understanding between cultures and exchanges between civil societies (Social, Cultural and Human Basket).

The European Union stated the intention of the partnership was "to strengthen its relations with the countries in the Mashriq and Maghreb regions". Both Ehud Barak and Yasser Arafat had high praises for Solana's coordination of the Barcelona Process. The Barcelona Process, developed after the Conference in successive annual meetings, is a set of goals designed to lead to a free trade area in the Middle East by 2010.

The agenda of the Barcelona Process is:

- Security and stability in the Mediterranean;

- Agreeing on shared values and initializing a long-term process for cooperation in the Mediterranean;

- Promoting democracy, good governance and human rights;

- Achieving mutually satisfactory trading terms for the region's partners, the "region" consisting of the countries that participated;

- Establishing a complementary policy to the United States' presence in the Mediterranean.

The Barcelona Process comprises three "baskets":

- economic - to work for shared prosperity in the Mediterranean, including the Association Agreements on the bilateral level

- political - promotion of political values, good governance and democracy

- cultural - cultural exchange and strengthening civil society

The Euro-Mediterranean free trade area (EU-MEFTA) is based on the Barcelona Process and European Neighbourhood Policy. The Agadir Agreement of 2004 is seen as its first building block.

At the time of its creation, the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership comprised 27 member countries: 15 from the European Union and 12 Mediterranean countries (Algeria, Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Malta, Morocco, the Palestinian Authority, Syria, Tunisia, and Turkey). As a result of the European Union's enlargements of 2004 and 2007 the number of EU member states grew up to 27, and two of the Mediterranean partner countries — Cyprus and Malta — became part of the European Union. The EU enlargement changed the configuration of the Barcelona Process from "15+12" to "27+10."[8] Albania and Mauritania joined the Barcelona Process in 2007, raising the number of participants to 39.[9]

Euromediterranean Summit 2005

The 10th anniversary Euromediterranean summit was held in Barcelona on 27–28 November 2005. Full members of the Barcelona Process were:

- 27 Member States of the European Union.

- 10 countries from the southern Mediterranean shore: Algeria, Palestinian Authority, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Syria, Tunisia, and Turkey (already part of the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership, the latter began EU accession talks on 3 October).

- Croatia, a candidate to join the EU, which began accession talks on 3 October.

- The European Parliament, the European Commission, and the Secretary General of the Council of the EU

Moreover, the Barcelona Process included 6 countries and institutions participating as permanent observers (Libya, Mauritania, the Secretary-General of the Arab League) and invited observers, such as the European Investment Bank, the Arab Maghreb Union, the Anna Lindh Foundation for the Dialogue between Cultures, the Economical and Social Committee or the Euromed Economical and Social Councils.

According to the ISN, "Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas and Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan were the only leaders from the Mediterranean countries to attend, while those of Israel, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, and Egypt were not present."

Agenda

From the official web site, "The new realities and challenges of the 21st century make it necessary to update the Barcelona Declaration and create a new Action Plan (based on the good results of the Valencia Action Plan), encompassing four fundamental areas":[10]

- Peace, Security, Stability, Good Government, and Democracy.

- Sustainable Economic Development and Reform.

- Education and Cultural Exchange

- Justice, Security, Migration, and Social Integration (of Immigrants).

Bilateral relations

The European Union carries out a number of activities bilaterally with each country. The most important are the Euro-Mediterranean Association Agreements that the Union negotiates with the Mediterranean Partners individually. They reflect the general principles governing the new Euro-Mediterranean relationship, although they each contain characteristics specific to the relations between the EU and each Mediterranean Partner.

Regional aspects

Regional dialogue represents one of the most innovative aspects of the Partnership, covering at the same time the political, economic and cultural fields (regional co-operation). Regional co-operation has a considerable strategic impact as it deals with problems that are common to many Mediterranean Partners while it emphasises the national complementarities.

The multilateral dimension supports and complements the bilateral actions and dialogue taking place under the Association Agreements.

Since 2004 the Mediterranean Partners are also included in the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) and since 2007 are funded via the ENPI.

The Euromed Heritage program

As a result of the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership, the Euromed Heritage program was formed. This program has been active since 1998, and has been involved in programs to identify the cultural heritages of Mediterranean states, promote their preservation, and educate the peoples of partner countries about their cultural heritages.[11]

Response

By some analysts, the process has been declared ineffective. The stalling of the Middle East Peace Process is having an impact on the Barcelona Process and is hindering progress especially in the first basket. The economic basket can be considered a success, and there have been more projects for the exchange on a cultural level and between the peoples in the riparian states. Other criticism is mainly based on the predominant role the European Union is playing. Normally it is the EU that is assessing the state of affairs, which leads to the impression that the North is dictating the South what to do. The question of an enhanced co-ownership of the process has repeatedly been brought up over the last years.

Being a long-term process and much more complex than any other similar project, it may be many years before a final judgement can be made.

Bishara Khader argues that this ambitious European project towards its Mediterranean neighbours has to be understood in a context of optimism. On the one hand, the European Community was undergoing important changes due to the reunification of Germany after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the beginning of the adhesion negotiations of Eastern and Central European countries. On the other, the Arab-Israeli conflict appeared to be getting closer to achieving peace after the Madrid Conference (1991) and the Oslo Accords (1992). As well, Khader states that the Gulf War of 1991, the Algerian crisis (from 1992 onwards) and the rise of Islamic fundamentalism throughout the Arab world are also important factors in Europe's new relations with the Mediterranean countries based on security concerns.[12]

Critiques against the Barcelona Process escalated after the celebration of the 10th Anniversary of the Euro-Mediterranean Summit in Barcelona in 2005, which was broadly considered a failure.[13] First, the absence of Heads of State and Government from the Southern Mediterranean countries (with the exception of the Palestinian and Turkish ones) heavily contrasted with the attendance of the 27 European Union's Heads of State and Government.[14] Second, the lack of consensus to define the term "terrorism" prevented the endorsement of a final declaration. The Palestinian Authority, Syria and Algeria argued that resistance movements against foreign occupation should not be included in this definition.[15] Nevertheless, a code of conduct on countering terrorism and a five-year work program were approved at Barcelona summit of 2005.[16] both of which are still valid under the Union for the Mediterranean.[17]

For many, the political context surrounding the 2005 summit — the stagnation of the Middle East Peace Process, the US-led war on Iraq, the lack of democratisation in Arab countries, and the war on terror's negative effects on freedoms and human rights, among others — proved for many the inefficiency of the Barcelona Process for fulfilling its objectives of peace, stability and prosperity.[18] Given these circumstances, even politicians that had been engaged with the Barcelona Process since its very beginnings, like the Spanish politician Josep Borrell, expressed their disappointment about the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership and its incapacity to deliver results.[19] Critiques from Southern Mediterranean countries blamed the Partnership's failure on Europe's lack of interest towards the Mediterranean in favour of its Eastern neighbourhood;[20] whereas experts from the North accused Southern countries of only being interested on "their own bi-lateral relationship with the EU" while downplaying multilateral policies.[19]

However, many European Union diplomats have defended the validity of the Barcelona Process' framework by arguing that the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership was the only forum that gathered Israelis and Arabs on equal footing[21]), and identifying as successes the Association Agreements, the Code of Conduct on Countering Terrorism and the establishment of the Anna Lindh Foundation for the Dialogue between Cultures.[1]

On 2006 the first proposals for improving the Partnership's efficiency, visibility and co-ownership arouse, such as establishing a co-presidency system and a permanent secretariat or nominating a "Mr./Ms. Med."[22]

Mediterranean Union

A proposal to establish a "Mediterranean Union", which would consist principally of Mediterranean states, was part of the election campaign of Nicolas Sarkozy during the French presidential election campaign in 2007. During the campaign Mr. Sarkozy said that the Mediterranean Union would be modelled on the European Union with a shared judicial area and common institutions.[23] Sarkozy saw Turkish membership of the Mediterranean Union as an alternative to membership of the European Union, which he opposes,[23] and as a forum for dialogue between Israel and its Arab Neighbours.[24]

Once elected, President Sarkozy invited all heads of state and government of the Mediterranean region to a meeting in June 2008 in Paris, with a view to laying the basis of a Mediterranean Union.[25]

The Mediterranean Union was enthusiastically supported by Egypt and Israel.[26] Turkey strongly opposed the idea and originally refused to attend the Paris conference until it was assured that membership of the Mediterranean Union was not being proposed as an alternative to membership of the EU.[27]

Among EU member states, the proposal was supported by Italy, Spain,[28] and Greece.[29]

However the European Commission and Germany were more cautious about the project. The European Commission saying that while initiatives promoting regional co-operation were good, it would be better to build them upon existing structures, notable among them being the Barcelona process. German chancellor Angela Merkel said the MU risked splitting and threatening the core of the EU. In particular she objected to the potential use of EU funds to fund a project which was only to include a small number of EU member states.[30] When Slovenia took the EU presidency at the beginning of 2008, the then Slovenian Prime Minister Janez Janša added to the criticism by saying: "We do not need a duplication of institutions, or institutions that would compete with EU, institutions that would cover part of the EU and part of the neighbourhood."[31]

Other criticisms of the proposal included concern about the relationship between the proposed MU and the existing Euromediterranean Partnership (Barcelona Process), which might reduce the effectiveness of EU policies in the region and allow the southern countries to play on the rivalries to escape unpopular EU policies. There were similar economic concerns in the loss of civil society and similar human rights based policies. Duplication of policies from the EU's police and judicial area was a further worry.[32]

Proposal scaled down

At the start of 2008 Sarkozy began to modify his plans for the Mediterranean Union due to widespread opposition from other EU member states and the European Commission. At the end of February of that year, France's minister for European affairs, Jean-Pierre Jouyet, stated that "there is no Mediterranean Union" but rather a "Union for the Mediterranean" that would only be "completing and enriching" to existing EU structures and policy in the region.[33] Following a meeting with German Chancellor Angela Merkel it was agreed that the project would include all EU member states, not just those bordering the Mediterranean, and would be built upon the existing Barcelona process. Turkey also agreed to take part in the project following a guarantee from France that it was no longer intended as an alternative to EU membership.[27]

The proposed creation of common institutions,[34] and a Mediterranean Investment, which was to have been modelled on the European Investment Bank, was also dropped.[35]

In consequence the new Union for the Mediterranean would consist of regular meeting of the entire EU with the non-member partner states, and would be backed by two co-presidents and a secretariat.

Union for the Mediterranean launched

At the Paris Summit for the Mediterranean (13 July 2008), the 43 Heads of State and Government from the Euro-Mediterranean region decided to launch the Barcelona Process: Union for the Mediterranean. It was presented as a new phase Euro-Mediterranean Partnership with new members and an improved institutional architecture which aimed to "enhance multilateral relations, increase co-ownership of the process, set governance on the basis of equal footing and translate it into concrete projects, more visible to citizens. Now is the time to inject a new and continuing momentum into the Barcelona Process. More engagement and new catalysts are now needed to translate the objectives of the Barcelona Declaration into tangible results."[17]

The Paris summit was considered a diplomatic success for Nicolas Sarzoky.[36] The French president had managed to gather in Paris all the Heads of State and Government from the 43 Euro-Mediterranean countries, with the exception of the kings of Morocco and Jordan.[37]

At the Euro-Mediterranean Conference of Foreign Affairs held in Marseilles in November 2008, the Ministers decided to shorten the initiative's name to simply the "Union for the Mediterranean".[5]

Aims and concrete projects

The fact that the Union for the Mediterranean is launched as a new phase of the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership means that the Union accepts and commits to maintain the acquis of Barcelona, the purpose of which is to promote "peace, stability and prosperity" throughout the region (Barcelona, 2). Therefore, the four chapters of cooperation developed in the framework of the Barcelona Process during thirteen years remain valid:[17]

- Politics and Security

- Economics and Trade

- Socio-cultural

- Justice and Interior Affairs. This fourth chapter was included at the 10th Anniversary Euro-Mediterranean Summit held in Barcelona in 2005.

The objective to establish a Free Trade Area in the Euro-Mediterranean region by 2010 (and beyond), first proposed at the 1995 Barcelona Conference, was also endorsed by the Paris Summit of 2008.[17]

In addition to these four chapters of cooperation, the 43 Ministers of Foreign Affairs gathered in Marseilles on November 2008 identified six concrete projects that target specific needs of the Euro-Mediterranean regions and that will enhance the visibility of the Partnership:[38]

- De-pollution of the Mediterranean. This broad project encompasses many initiatives that target good environmental governance, access to drinkable water, water management, pollution reduction and protection of the Mediterranean biodiversity.[1]

- Maritime and land highways. The purpose of this project is to increase and improve the circulation of commodities and people throughout the Euro-Mediterranean region by improving its ports, and building highways and railways. Specifically, the Paris and Marseilles Declarations refer to the construction of both a Trans-Maghrebi railway and highway systems, connecting Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia.[1]

- Civil protection. The civil protection project aims at improving the prevention, preparedness and response to both natural and man-made disasters. The ultimate goal is to "bring the Mediterranean Partner Countries progressively closer to the European Civil Protection Mechanism.[39]

- Alternative energies: Mediterranean solar plan. The goal of this project is to promote the production and use of renewable energies. More specifically, it aims at turning the Mediterranean partner countries into producers of solar energy and then circulating the resulting electricity through the Euro-Mediterranean region.[1] In this connection the union and the industrial initiative Dii signed a Memorandum of Understanding for future collaboration in May 2012 which included developing their long-term strategies "Mediterranean Solar Plan" and "Desert Power 2050". At the signing in Marrakesh the union's Secretary General called the new partnership "a key step for the implementation of the Mediterranean Solar Plan."[40]

- Higher education and research: Euro-Mediterranean University. On June 2008 the Euro-Mediterranean University of Slovenia was inaugurated in Piran (Slovenia), which offers graduate studies programs. The Foreign Ministers gathered at Marseilles on 2008 also called for the creation of another Euro-Mediterranean University in Fes, Morocco, Euro-Mediterranean University of Morocco (Euromed-UM).[41] The decision to go ahead with the Fes university was announced in June 2012.[42] At the 2008 Paris summit, the 43 Heads of State and Government agreed that the goal of this project is to promote higher education and scientific research in the Mediterranean, as well as to establish in the future a "Euro-Mediterranean Higher Education, Science and Research Area."[17]

- The Mediterranean business development initiative. The purpose of the initiative is to promote small and medium-sized enterprises from the Mediterranean partner countries by "assessing the needs of these enterprises, defining policy solutions and providing these entities with resources in the form of technical assistance and financial instruments." [17]

Projects

- 2013

In 2013, three new projects were launched so far:

- Young Women as Job Creators - The project promotes self-employment and entrepreneurship among young women university students who are about to graduate in Jordan, Morocco, Palestine and Spain, with an interest in starting their own business.

- Governance & Financing for the Mediterranean Water Sector - The core objective is to diagnose key governance and capacity building bottlenecks to mobilizing financing through public private partnerships (PPP) for the Mediterranean water sector and to support the development of consensual action plans based on international good practices.

- LOGISMED Training Activities (LOGISMED-TA). - LOGISMED-TA aims at improving the level of qualifications in the logistics sector by reinforcing logistics training structures in the Southern Mediterranean member countries. It more specifically focuses on the constitution of a network of experts and trainers at various levels who will lead the transformation of the transport and logistics sectors and create a Euro-Mediterranean market of logistic specialists.

Institutions

In contrast with the Barcelona Process, one of the biggest innovations of the Union for the Mediterranean is its institutional architecture. It was decided at the Paris Summit to provide the Union with a whole set of institutions in order to up-grade the political level of its relations, promote a further co-ownership of the initiative among the EU and Mediterranean partner countries and improve the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership's visibility.[17][43]

Biennial summits of heads of state and government

A summit of heads of state and government is intended to be held every two years to foster political dialogue at the highest level. According to the Paris Declaration:

- these summits should produce a joint declaration addressing the situation and challenges of the Euro-Mediterranean region, assessing the works of the Partnership and approving a two-year work program;[44]

- Ministers of Foreign Affairs should meet annually to monitor the implementation of the summit declaration and to prepare the agenda of subsequent summits;[44] and

- the host country of the summits would be chosen upon consensus and should alternate between EU and Mediterranean countries.[44]

The first summit was held in Paris in July 2008. The second summit should have taken place in a non-EU country in July 2010 but the Euro-Mediterranean countries agreed to hold the summit in Barcelona on 7 June 2010, under the Spanish presidency of the EU, instead.[45] However, on 20 May the Egyptian and French co-presidency along with Spain decided to postpone the summit, in a move which they described as being intended to give more time to the indirect talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority that had started that month. In contrast, the Spanish media blamed the postponement on the Arab threat to boycott the summit if Avigdor Lieberman, Israel's Minister of Foreign Affairs, attended the Foreign Affairs conference prior to the summit.[46]

After the initial postponement, both France and Spain announced their intentions to hold peace talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority as part of the postponed summit under the auspices of the US. In September, U.S. President Barack Obama was invited to the summit for this purpose. The summit which was then scheduled to take place in Barcelona on 21 November 2010,[47] was according to Nicolas Sarkozy, the summit was "an occasion to support the negotiations."[48]

Nevertheless, at the beginning of November 2010 the peace talks stalled, and the Egyptian co-presidents conditioned the occurrence of the summit on a gesture from Israel that would allow the negotiations to resume. According to some experts Benjamin Netanyahu's announcement of the construction of 1,300 new settlements in East Jerusalem ended all the possibilities of celebrating the summit on 21 November.[49] The two co-presidencies and Spain decided on 15 November to postpone the summit sine die, alleging that the stagnation of the Middle East Peace Process would hinder a "satisfactory participation."[50]

North and South Co-presidency system

With the purpose of guaranteeing the co-ownership of the Union for the Mediterranean, the Heads of State and Government decided in Paris that two countries, one from the EU and one from the Mediterranean partner countries, will jointly preside the Union for the Mediterranean. The 27 agreed that the EU co-presidency had to "be compatible with the external representation of the European Union in accordance with the Treaty provisions in force."[17] The Mediterranean partner countries decided to choose by consensus and among themselves a country to hold the co-presidency for a non-renewable period of two years."[17]

At the time of the Paris summit, France — which was in charge of the EU presidency — and Egypt held the co-presidency. Since then, France had been signing agreements with the different rotator presidencies of the EU (the Czech Republic, Sweden and Spain) in order to maintain the co-presidency for alongside Egypt.[1] The renewal of the co-presidency was supposed to happen on the second Union for the Mediterranean Summit. However, due to the two postponements of the summit, there has been no chance to decide which countries will take over the co-presidency. Spain had planned to replace France as the EU co-presidency of the Union for the Mediterranean. However, Belgium — the country presiding the EU for the second half of 2010 — opposed the Spanish aspirations.

In June 2012 the secretariat announced that the co-presidency of Egypt would be succeeded by Jordan. The change which is to take place in September 2012 was decided at a meeting of the high representatives in Barcelona on 28 June.[42]

Secretariat

The Secretariat of the Union for the Mediterranean was inaugurated on March 4, 2010 in an official ceremony in Barcelona.[51]

The task of the permanent Secretariat is to identify and monitor the implementation of concrete projects for the Euro-Mediterranean region, and to search for partners to finance these projects.[52]

The Euro-Mediterranean Ministers of Foreign Affairs decided at the Marseilles conference of November 2008 that the headquarters of the Secretariat would be at the Royal Palace of Pedralbes in Barcelona.[53] They also agreed on the structure of this new key institution and the countries of origin of its first members:

- The Secretary General is elected by consensus from a non-EU country. His term is for three years, which may be extended for another three.[52] The first Secretary General was the Jordanian Ahmad Khalaf Masa'deh, the former Ambassador of Jordan to the EU, Belgium, Norway and Luxembourg, and Minister of Public Sector Reform from 2004–2005.[54] He resigned after one year in office.[55] In March 2012 the Moroccan deputy foreign minister, Youssef Amrani was replaced as Secretary General by fellow Moroccan Fathallah Sijilmassi.[42][56]

- In order to enhance the co-ownership of the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership, six posts of Deputy Secretaries General were assigned to three countries from the EU and three from the Mediterranean partner countries. For the first term of three years (extendible to another three) the Deputy Secretaries General were:[57]

- Mrs. Teresa Ribeiro (Portugal) - Energy Division;

- Prof. Ilan Chet (Israel) - Higher Education and Research Division;

- Mr. Claudio Cortese (Italy) - Business Development Division;

- Amb. Delphine Borione (France) - Social and Civil Affairs Division;

- Dr. Rafiq Husseini (Palestine) - Water and Environment Division;

- Amb. Yigit Alpogan (Turkey) - Transport and Urban Development Division.

The Secretariat of the Union for the Mediterranean was inaugurated on March 2010 in an official ceremony in Barcelona.[51]

Euro-Mediterranean Parliamentary Assembly

The Euro-Mediterranean Parliamentary Assembly (EMPA) is not a new institution inside the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership framework. It was established in Naples on 3 December 2003 by the Euro-Mediterranean Ministers of Foreign Affairs and had its first plenary session in Athens on 22–23 March 2004. The EMPA gathers parliamentarians from the Euro-Mediterranean countries and has four permanent committees on the following issues:[58]

- Political Affairs, Security and Human Rights

- Economic, Financial and Social Affairs and Education

- Promotion of the Quality of Life, Human Exchanges and Culture

- Women's Rights in the Euro-Mediterranean Countries

The EMPA also has an ad hoc committee on Energy and Environment. Since the launch of the Union for the Mediterranean, the EMPA's role has been strengthened for it is considered the "legitimate parliamentary expression of the Union".[17]

Euro-Mediterranean Regional and Local Assembly

At the Euro-Mediterranean Foreign Affairs Conference held in Marseilles on November 2008, the Ministers welcomed the EU Committee of the Regions proposal to establish a Euro-Mediterranean Assembly of Local and Regional Authorities (ARLEM in French). Its aim is to bridge between the local and regional representatives of the 43 countries with the Union for the Mediterranean and EU institutions.[59]

The EU participants are the members of the EU Committee of the Regions, as well as representatives from other EU institutions engaged with the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership. From the Mediterranean partner countries, the participants are representatives of regional and local authorities appointed by their national governments. The ARLEM was formally established and held its first plenary session in Barcelona on 31 January 2010. The ARLEM's co-presidency is held by the President of the EU Committee of the Regions, Luc Van den Brande, and the Moroccan mayor of Al Hoceima, Mohammed Boudra.[60]

Anna Lindh Foundation

The Anna Lindh Foundation for the Dialogue between Cultures, with headquarters are in Alexandria, Egypt, was established in April 2005. It is a network for the civil society organisations of the Euro-Mediterranean countries, aiming at the promotion of intercultural dialogue and mutual understanding.[61]

At the Paris Summit it was agreed that the Anna Lindh Foundation, along with the UN Alliance of Civilizations will be in charge of the cultural dimension of the Union for the Mediterranean.[17]

In September 2010 the Anna Lindh Foundation published a report called "EuroMed Intercultural Trends 2010."[62] This evaluation about mutual perceptions and the visibility of the Union of the Mediterranean across the region is based on a Gallup Public Opinion Survey in which 13,000 people from the Union of the Mediterranean countries participated.

Funding

The Paris Declaration states that contributions for the Union for the Mediterranean will have to develop the capacity to attract funding from "the private sector participation; contributions from the EU budget and all partners; contributions from other countries, international financial institutions and regional entities; the Euro-Mediterranean Investment and Partnership Facility (FEMIP); the ENPI", among other possible instruments,[17]

- The European Commission contributes to the Union for the Mediterranean through the European Neighbourhood Policy Instrument (ENPI). In July 2009 the ENPI allocated €72 million for the following Union for the Mediterranean projects during 2009–2010:[63]

- De-pollution of the Mediterranean (€22 million).

- Maritime and land highways (€7.5 million).

- Alternative energies: Mediterranean Solar Plan (€5 million).

- Euro-Mediterranean University of Slovenia (€1 million)

- The European Neighbourhood Instrument (ENI) came into force in 2014. It is the financial arm of the European Neighbourhood Policy, the EU’s foreign policy towards its neighbours to the East and to the South. It has a budget of €15.4 billion and will provide the bulk of funding through a number of programmes. The ENI, effective from 2014 to 2020, replaces the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument – known as the ENPI.

- The European Investment Bank contributes to the Union for the Mediterranean through its Euro-Mediterranean Investment and Partnership (FEMIP). Specifically, the FEMIP was mandated by the Euro-Mediterranean Ministers of Finance on 2008 to support three of the six concrete projects: the de-pollution of the Mediterranean; alternative energies; and maritime and land highways.[64] Following the June 2012 meeting the EIB announced it would give 500 million euros to support projects for the UfM.[42]

- The InfraMed Infrastructure Fund was established in June 2010 by five financial entities: the French Caisse des Dépôts, the Moroccan Caisse de Dépôts et de Gestion, the Egyptian EFG Hermes, the Italian Cassa Depositi e Prestiti and the European Investment Bank. On an initial phase, the Fund will contribute €385 million to the Secretariat's projects on infrastructure.[65]

- The World Bank has allocated $750 million for the renewable energy project through the Clean Technology Fund.[1]

Impact of conflicts between member countries

Among the 43 member countries of the Union for the Mediterranean, there are three unresolved conflicts that hinder the works of the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership: the Arab-Israeli, Cyprus-Turkish and Western Sahara (which, unlike the Palestinian Authority, is not part of the Union for the Mediterranean.)[66] The European Union Ambassador to Morocco, Eneko Landaburu, stated on September 2010 that he does "not believe" in the Union for the Mediterranean. According to him, the division among the Arabs "does not allow to implement a strong inter-regional policy", and calls to leave this ambitious project of 43 countries behind and focus on bilateral relations.[67]

The fact that all the decisions, from the lowest to the highest level, in the Union for the Mediterranean are taken "by the principle of consensus"[17] facilitates the blockage of the Partnership's work every time tensions rise between the countries involved in these conflicts.[68]

Due to its seriousness, the Arab-Israeli conflict is the one that most deeply affects the Union for the Mediterranean.[68] As a result of Israel's operation against the Hamas regime in Gaza Strip at the end of 2008 and the beginning of 2009, the Arab Group refused to meet at high level, thus blocking all the ministerial meetings scheduled for the first half of 2009.[69] As well, the refusal of the Arab Ministers of Foreign Affairs to meet with their Israeli counterpart, Avigdor Lieberman, resulted in the cancellation of two ministerial meetings on Foreign Affairs on November 2009 and June 2010.[70] Sectorial meetings of the Union for the Mediterranean have also been affected by Arab attempts to push forward an anti-Israel ideology. At the Euro-Mediterranean ministerial meeting on Water, held in Barcelona on April 2010, the Water Strategy was not approved due to a terminological disagreement of whether to refer to territories claimed by Palestinians, Syrians and Lebanese as "occupied territories" or "territories under occupation."[71] Two other ministerial meetings, on higher education and agriculture, had to be cancelled because of the same discrepancy.[72]

The conflict between Turkey and Cyprus has been responsible for the delay in the endorsement of the statutes of the Secretariat,[73] which were only approved in March 2010 even though the Marseille declaration set May 2009 as the deadline for the Secretariat to start functioning.[74] At the Paris summit, the Heads of State and Government agreed to establish five Deputy Secretaries General from Greece, Israel, Italy, Malta and the Palestinian Authority. Turkey's desire to have a Deputy Secretary General and Cyprus' rejection of it, resulted in months of negotiation until Cyprus finally approved the creation of a sixth Deputy Secreaty General post assigned to a Turkish citizen.[73]

Western Sahara is a source of conflict between Algeria and Morocco. The lack of diplomatic relations among these two countries, along with the unresolved dispute over the sovereignty of Western Sahara, prevent the implementation of any intra-Maghreb projects,[75] such as the railway and highway initiatives, as the stagnation of the Arab Maghreb Union proves.[76]

List of Sectorial Ministerial meetings

- Economic-Financial Meeting, 7 October 2008, Luxembourg. Conclusions.

- Industry, 5–6 November 2008, Nice (France). Conclusions.

- Employment and Labor, 9–10 November 2008, Marrakech (Morocco). Conclusions.

- Health, 11 November 2008, Cairo (Egypt). Conslusions.

- Water, 22 December 2008, Amman (Jordan). Conclusions.

- Sustainable Development, 25 June 2009, Paris (France). Conclusions.

- Economic-Financial Meeting, 7 July 2009, Brussels (Belgium). Conslusions.

- Strengthening the Role of Women in Society, 11–12 November, Marrakech (Morocco). Conclusions.

- Trade, 9 December 2009, Brussels (Belgium). Conclusions.

- Water, 21–22 April 2010, Barcelona (Spain).

- Tourism, 20 May 2010, Barcelona (Spain).

See also

- European Neighbourhood Policy

- Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation

- Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation

- Indian Ocean Rim Association for Regional Cooperation

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "El Partenariado Euro-Mediterráneo: del Proceso de Barcelona a la Unión por el Mediterráneo" (in Spanish). Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores y de Cooperación. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ Camilleri, Ivan (13 September 2011). "Med Union wants Libya as full member". Times of Malta. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ↑ Abu Najm, Michel (2013-10-26). "Libyan FM on Border Security, Militias". Asharq Al-Awsat. Retrieved 2013-11-05.

- ↑ The Euro-Mediterranean Ministers of Foreign Affairs gathered at Marseilles on November 2008, agreed that the League of the Arab States "shall participate in all meetings at all levels" of the Union for the Mediterranean. Prior to this decision, the Arab League had been participating in Ministerial Meetings of the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership but was not allowed in the preparatory meetings.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Final Statement of the Marseille Meeting of the Euro-Mediterranean Ministers of Foreign Affairs (PDF). 3–4 November 2008. p. 1.

- ↑ Khader, Bichara (2009). Europa por el Mediterráneo. De Barcelona a Barcelona (1995–2009) (in Spanish). Icaria. p. 23. ISBN 978-84-9888-107-3.

- ↑ Barcelona Declaration, adopted at the Euro-Mediterranean Conference (PDF). 27–28 November 1995.

- ↑ Khader, Bichara (2009). Europa por el Mediterráneo. De Barcelona a Barcelona (1995–2009) (in Spanish). Icaria. p. 27. ISBN 978-84-9888-107-3.

- ↑ Montobbio, Manuel (2009). "Coming Home.Albania in the Barcelona Process:Union for the Mediterranean" (PDF). Anuario (IEMed). Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ http://www.euromedbarcelona.org/EN/PtoEncuentro/ACptoEncuentro/index.html

- ↑ "Mediterranean Heritage projects page". Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ↑ Khader, Bishara (2009). Europa por el Mediterráneo. De Barcelona a Barcelona (1995–2009) (in Spanish). Icaria. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-84-9888-107-3.

- ↑ "Barcelona: Report on a Predicted Failure". Voltaire. 14 December 2005. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ "Editorial: Summit Drama – and Beyond" (PDF) (2). EuroMesco. December 2005.

- ↑ Cruz, Marisa (28 November 2005). "España y sus socios europeos asumen que la Cumbre puede saldarse hoy con un fracaso". El Mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ "La cumbre de Barcelona consigue acordar un Código de Conducta Antiterrorista". El Pais (in Spanish). 28 November 2005. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 17.7 17.8 17.9 17.10 17.11 17.12 Joint Declaration of the Paris Summit for the Mediterranean (PDF). 13 July 2008. p. 12.

- ↑ Fernández, Haizam Amirah; Youngs, Richard (30 November 2005). "The Barcelona Process: An Assessment of a Decade of the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership" (PDF). Real Instituto Elcano (137). Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Borrell, Josep (Autumn 2010). "Yes the Barcelona Process was "mission impossible", but the EU can learn from that". EuropesWorld. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ "Partial setback for Barcelona summit". Magharebia. 30 November 2005. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ Khader, Bichara (2009). Europa por el Mediterráneo. De Barcelona a Barcelona (1995–2009) (in Spanish). Icaria. p. 21. ISBN 978-84-9888-107-3.

- ↑ Soler i Lechaq, Eduard (February 2008). "España y el Mediterráneo:" (PDF). España en Europa 2004–2008 (in Spanish) 4 (Observatorio de Política Exterior, Institut Universitari d'Estudis Europeus). Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Holm, Carl (13 February 2007). "Sparks Expected to Fly Whoever Becomes France's President". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ↑ Bennhold, Katrin; Burnett, Victoria; Kiefer, Peter (10 May 2007). "Sarkozy's proposal for Mediterranean bloc makes waves". International Herald Tribune (The New York Times). Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ↑ Goldirova, Renata (25 October 2007). "France muddies waters with 'Mediterranean Union' idea". EUobserver.

- ↑ Mediterranean Union: EJP 7 May 2007

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Turkey, reassured on EU, backs 'Club Med' plan, The Guardian 4 March 2008.

- ↑ "Sarkozy Gets Italy, Spain on Board for "Mediterranean Union"". Deutsche Welle. 21 December 2007. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

- ↑ Sarkozy Karamanlis talks

- ↑ Mahony, Honor (6 December 2007). "Merkel criticises Sarkozy's Mediterranean Union plans". EUobserver.

- ↑ Keller, Caroline (17 January 2008). "Slovenia criticises French Mediterranean Union proposal". EUobserver.

- ↑ Behr, Timo; Ruth Hanau Santini (12 November 2007). "Comment: Sarkozy's Mediterranean union plans should worry Brussels". EUobserver.

- ↑ Vucheva, Elitsa (27 February 2008) France says it has no preferred EU president candidate, EU Observer

- ↑ "EU Leaders Show Muted Enthusiasm for Club Med Plans". Der Spiegel. 14 March 2008. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- ↑ Balmer, Crispian (4 March 2008) Sarkozy's Med dream deflated by Germany, Reuters

- ↑ "43 pays à Paris pour lancer l'Union pour la Méditerranée". EurActiv.fr (in French). 13 July 2008. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ "Nicolas Sarkozy's New 'Club Med'". Der Spiegel. 14 July 2008. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ Final Statement of the Marseille Meeting of the Euro-Mediterranean Ministers of Foreign Affairs (PDF). 3–4 November 2008. p. 4.

- ↑ Final Statement of the Marseille Meeting of the Euro-Mediterranean Ministers of Foreign Affairs (PDF). 3–4 November 2008. pp. 20–21.

- ↑ "Mediterranean efforts for renewable energy united – UfM and Dii join forces" (Press release). EcoSeed. 17 May 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ↑ Final Statement of the Marseille Meeting of the Euro-Mediterranean Ministers of Foreign Affairs (PDF). 3–4 November 2008. p. 21.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 "UfM: Jordan to hold co-presidency of south Med from Sept.". ANSAmed. 29 June 2012. Archived from the original on 4 July 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ↑ Joint Declaration of the Paris Summit for the Mediterranean, 13 July 2008, p. 13

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Joint Declaration of the Paris Summit for the Mediterranean (PDF). 13 July 2008. p. 13.

- ↑ "La Cumbre de la Unión por el Mediterráneo se celebrará en Barcelona en junio de 2010". El País (in Spanish). 10 September 2009. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ "El actual conflicto árabe-israelí obliga a aplazar la cumbre de Barcelona". El Periódico Mediterráneo (in Spanish). 21 May 2010. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ "El Consejo de Europa confirma que se celebrará la cumbre euro-mediterráneo de noviembre en Barcelona". Medlognews (in Spanish). 16 September 2010. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ "El Gobierno español quiere a Obama en la Cumbre Mediterránea de noviembre". MedLog Newa (in Spanish). 9 June 2010. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ↑ "España da por imposible la cumbre mediterránea de Barcelona". El Pais (in Spanish). 10 November 2010. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ↑ "Postponement of the Union for the Mediterranean Summit". La Moncloa. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 "La Unión por el Mediterráneo ya ejerce en Barcelona". Medlognews (in Spanish). 6 March 2010. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Final Statement of the Marseille Meeting of the Euro-Mediterranean Ministers of Foreign Affairs (PDF). 3–4 November 2008. p. 6.

- ↑ "Barcelona, capital del Mediterráneo". El País (in Spanish). 5 November 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ "Biography: H.E. Dr. Ahmad Masa'deh" (PDF). Generalitat de Catalunya, Secretaria per a la Unió Europea. 2008. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ↑ "Dimite el secretario de la Unión por el Mediterráneo tras un año en el cargo". La vanguardia (in Spanish). EFE. 26 January 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ↑ "Planning minister, international experts discuss economic situation in Jordan". Amman, Jordan. Jordan News Agency. 6 June 2012. Archived from the original on 6 June 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ↑ "El Secretariado de Barcelona camina a trancas y barrancas". El periódico (in Spanish). 28 October 2010. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ "Euro-Mediterranean Assembly". Mediterranean Commission, United Cities and Local Governments. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ "What is the ARLEM?". EU Committee of the Regions. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ "ARLEM". Council of European Municipalities and Regions. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ "Anna Lindh Foundation". Anna Lindh Foundation. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ "Anna Lindh Report 2010". Anna Lindh Foundation. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ "Union for the Mediterranean: Commission increases its contribution to priority projects". ENPI, Union for the Mediterranean. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ "FEMIP and the Union for the Mediterranean". EIB. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ "Cinco entidades financieras crean el primer fondo de inversión en infraestructuras para el Mediterráneo". 26 May 2010. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ Khader, Bichara (2009). Europa por el Mediterráneo. De Barcelona a Barcelona (1995–2009) (in Spanish). Icaria. p. 205. ISBN 978-84-9888-107-3.

- ↑ "El embajador de la UE en Marruecos "no cree" en la Unión por el Mediterráneo". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 28 September 2010. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 de la Vaissiere, Jean-Louis (14 April 2010). "La Unión por el Mediterráneo todavía está lejos de servir como motor de paz". AFP (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ Martín, Iván (9 December 2009). "Las prioridades de la Presidencia española de la UE en el Mediterráneo: ser y deber ser (ARI)". Real Instituto Elcano (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ Radigales, Montserrat (21 May 2010). "El actual conflicto árabe-israelí obliga a aplazar la cumbre de Barcelona". El Periódico Mediterráneo (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ "La Unión por el Mediterráneo no logra una estrategia común sobre el agua". El Mundo (in Spanish). 13 April 2010. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ Radigales, Montserrat (28 October 2010). "La Unión por el Mediterráneo, atascada, se juega el futuro". El Periódico (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 "La UpM aprueba hoy sus estatutos y lanza la capitalidad mediterránea de Barcelona". EcoDiario (in Spanish). 3 March 2010. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ Final Statement of the Marseille Meeting of the Euro-Mediterranean Ministers of Foreign Affairs (PDF). 3–4 November 2008. p. 7.

- ↑ "Sarkozy's Mediterranean Union on Hold". Europafrica. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ Martínez, Luis (October 2006). "Algeria, the Arab Magrheb Union and regional integration" (PDF). EuroMesco. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Union for the Mediterranean. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||