Unifon

Unifon is a phonemic orthography for English designed in the mid-1950s by Dr. John R. Malone, a Chicago economist and newspaper equipment consultant. It was developed into a teaching aid to help children acquire reading and writing skills. Like the pronunciation key in a dictionary, Unifon matches each of the sounds of spoken English with a single symbol. The method was tested in Chicago, Indianapolis, and elsewhere during the 1960s and 1970s, but no statistical analysis of the outcome was ever published in an academic journal, and interest by educators has been limited, although a community of enthusiasts continues to publicize the scheme and advocate for its adoption.[1]

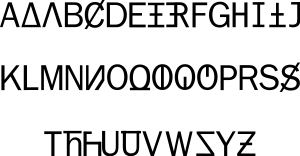

Unifon alphabet

The Unifon alphabet contains 40 glyphs, intended to represent the 40 most important sounds of the English language. Although the set of sounds has remained the same, several of the symbols have been modified over the years, making "Modern Unifon" subtly different from "Old Unifon".

History

Under a contract with the Bendix Corporation, Dr. John R. Malone created the alphabet as part of a larger project. When the International Air Transport Association selected English as the language of international airline communications in 1957, the market that Bendix had foreseen for Unifon ceased to exist, and Malone’s contract was terminated. According to Malone, Unifon surfaced again when his son, then in kindergarten, complained that he couldn’t read yet. Malone recovered the alphabet to teach his son.[2]

Beginning before 1960 and continuing into the 1980s, Margaret S. Ratz used Unifon to teach first-graders at Principia College in Elsah, Illinois.[3] By the summer of 1960, the ABC-TV affiliate station in Chicago produced a 90-minute program in which Dr. Ratz taught three children how to read, in “17 hours with cookies and milk,” as Malone described it. In a presentation to parents and teachers, Dr. Ratz said, “Some have called Unifon ‘training wheels for reading,’ and that’s what it really is. Unifon will be used for a few weeks, or perhaps a few months, but during this time your child will discover there is a great similarity between Unifon and what he sees on TV screens, in comics or road signs, and on cereal boxes. Soon he finds with amusement that he can read the ‘old people’s alphabet’ as easily as he can read and write in Unifon.”

During the following two years, Unifon gained national attention, with coverage from NBC’s Today Show and CBS's On the Road with Charles Kuralt (in a segment called “The Day They Changed the Alphabet”).

In 1981, Malone turned over the Unifon project to Dr. John M. Culkin, a media scholar who was a former Jesuit priest and Harvard School of Education graduate. Culkin wrote numerous articles about Unifon, including several in Science Digest.

In 2000, the Unifon web site, http://www.unifon.org, was created by Pat Katzenmaier with much input from linguist Steve Bett, and has served since then as a central point for organization of Unifon-related efforts.

Unifon for Native American languages

In the 1970s and 1980s, a systematic attempt was made to adapt Unifon as a spelling system for several Native American languages. The chief driving force behind this effort was Tom Parsons of Humboldt State University, who developed spelling schemes for the Hupa, Yurok, Tolowa, and Karok languages, which were then improved by native scholars. In spite of skepticism from linguists, years of work went into teaching these schemes, and numerous publications were written using them. In the end, however, the idea never caught fire, and once Parson left the university, the impetus faded; other spelling schemes are currently used for all of these languages.[4]

Adoption

Although Unifon was made available to a number of schools in the early 1960s, it was overshadowed by another initial teaching alphabet, Pitman's Augmented Roman. This came to be known as the i.t.a. and was supported with $20 million in research grants in the US and the UK. By comparison, Unifon had relatively little outside support. Various grants to the Unifon Foundation totaled around $1 million.

To complicate matters Unifon was completely at odds with conventional wisdom. Most educators doubted that preschool children were ready for reading let alone writing. The Unifon classes demonstrated that once the kids learned the 40 sound-symbol correspondences, they started writing and were code literate in less than 3 months.

The i.t.a. allowed teachers to teach as they had always taught except their basal readers would now be transcribed into Pitman's augmented Roman. Children progressed through their transcribed readers twice as fast as their peers using traditional readers. However, in the 3rd year when students transitioned to traditional spelling, they lost most of their advantage. The i.t.a. or initial teaching alphabet, failed to accelerate conventional literacy.

While i.t.a. students learned word-signs, 50% never overlearned the code. Half of the i.t.a. trained students could not spell words that were not included in the controlled vocabulary of their readers. By contrast, all of the Unifon trained students could string together sound-signs for any word they could pronounce and pronounce any Unifon spelling by the 3rd month. They were code literate. They could comprehend transcribed text as well as they could comprehend the text that was read to them.

Although upper case Unifon did not resemble traditional spelling nearly as much as lower case i.t.a. with its ligatured digraphs, children were still able to make the transition.

Downing had predicted that if the code was overlearned, the skills developed learning the simple orthography would transfer. The i.t.a. failed to accelerate literacy because at least half of the students did not overlearn the code and because the teaching method used was designed to promote whole-word recognition. Students who learned that "show your shoes" was spelled "[sh][oe] ywr [sh][oo]z" had some unlearning to do. Simulated Unifon: $Ó Y3R $ÚZ.

Character set support

The special non-ASCII characters used in the Unifon alphabet have been assigned code points in one of the Unicode Private Use Areas by the ConScript Unicode Registry.[5] Efforts are in progress to add these characters to the official Unicode character set.

Notes

- ↑ www.unifon.org

- ↑ Malone

- ↑ Ratz

- ↑ Hinton, pp 244-245

- ↑ "Unifon: U+E740 - U+E76F". ConScript Unicode Registry. Retrieved 2012-05-30.

References

- "The Unifon Alphabet". Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- Malone, John R. "Do we need a new alphabet?" (pdf). Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- Rátz, Margaret S. (1966). Unifon: A design for teaching reading. Western Pub. Educational Services.

- Hinton, Leanne (2001). "Ch 19. New Writing Systems". In Hinton L, Hale K. The Green Book of Language Revitalization in Practice: Toward a Sustainable World. Emerald Group Publishing. ISBN 978-0-12-349354-5.

- Culkin, John (1977). "The Alphubet". Media and Methods 14: 58–61.