Ulna

| Ulna | |

|---|---|

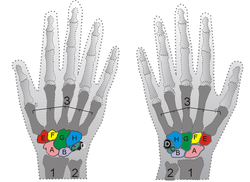

Position of ulna (shown in red) | |

Shown is the right hand, palm down (left) and palm up (right). Ulna is #2 | |

| Details | |

| Latin | Ulna |

| Identifiers | |

| Gray's | p.214 |

| MeSH | A02.835.232.087.090.850 |

| Dorlands /Elsevier | u_01/12835497 |

| TA | A02.4.06.001 |

| FMA | 23466 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The ulna (/ˈʌlnə/[1][2]) or elbow bone (Latin, "elbow") is one of the two long bones in the forearm, the other being the radius. It is prismatic in form and runs parallel to the radius, which is shorter and smaller. In anatomical position (i.e. when the arms are down at the sides of the body and the palms of the hands face forward) the ulna is located at the side of the forearm closest to the body (the medial side), the side of the little finger.

Structure

Articulations

The ulna articulates with:

- trochlea of the humerus, at the right side elbow as a hinge joint with semilunar trochlear notch of the ulna.

- the radius, near the elbow as a pivot joint, this allows the radius to cross over the ulna in pronation.

- the distal radius, where it fits into the ulnar notch.

- the radius along its length via the interosseous membrane that forms a syndesmosis joint

Proximal and distal aspects

The ulna is broader proximally, and narrower distally.

Proximally, the ulna has a bony process, the olecranon process, a hook-like structure that fits into the olecranon fossa of the humerus. This prevents hyperextension and forms a hinge joint with the trochlea of the humerus. There is also a radial notch for the head of the radius, and the ulnar tuberosity to which muscles attach.

At the distal end of the ulna is a styloid process.

The long, narrow medullary cavity is enclosed in a strong wall of compact tissue which is thickest along the interosseous border and dorsal surface. At the extremities the compact layer thins. The compact layer is continued onto the back of the olecranon as a plate of close spongy bone with lamellæ parallel. From the inner surface of this plate and the compact layer below it trabeculæ arch forward toward the olecranon and coronoid and cross other trabeculæ, passing backward over the medullary cavity from the upper part of the shaft below the coronoid. Below the coronoid process there is a small area of compact bone from which trabeculæ curve upward to end obliquely to the surface of the semilunar notch which is coated with a thin layer of compact bone. The trabeculæ at the lower end have a more longitudinal direction.[3]

Muscle attachments

| Muscle | Direction | Attachment |

| Triceps brachii muscle | Insertion | posterior part of superior surface of Olecranon process (via common tendon) |

| Anconeus muscle | Insertion | olecranon process (lateral aspect) |

| Brachialis muscle | Insertion | anterior surface of the coronoid process of the ulna |

| Pronator teres muscle | Origin | medial surface on middle portion of coronoid process (also shares origin with medial epicondyle of the humerus) |

| Flexor carpi ulnaris muscle | Origin | olecranon process and posterior surface of ulna (also shares origin with medial epicondyle of the humerus) |

| Flexor digitorum superficialis muscle | Origin | coronoid process (also shares origin with medial epicondyle of the humerus and shaft of the radius) |

| Flexor digitorum profundus muscle | Origin | coronoid process, anteromedial surface of ulna (also shares origin with the interosseous membrane) |

| Pronator quadratus muscle | Origin | distal portion of anterior ulnar shaft |

| Extensor carpi ulnaris muscle | Origin | posterior border of ulna (also shares origin with lateral epicondyle of the humerus) |

| Supinator muscle | Origin | proximal ulna (also shares origin with lateral epicondyle of the humerus) |

| Abductor pollicis longus muscle | Origin | posterior surface of ulna (also shares origin with the posterior surface of the radius bone) |

| Extensor pollicis longus muscle | Origin | dorsal shaft of ulna (also shares origin with the dorsal shaft of the radius and the interosseous membrane) |

| Extensor indicis muscle | Origin | posterior surface of distal ulna (also shares origin with the interosseous membrane) |

Development

The ulna is ossified from three centers: one each for the body, the inferior extremity, and the top of the olecranon.

Ossification begins near the middle of the body, about the eighth week of fetal life, and soon extends through the greater part of the bone.

At birth the ends are cartilaginous.

About the fourth year, a center appears in the middle of the head, and soon extends into the ulnar styloid process.

About the tenth year, a center appears in the olecranon near its extremity, the chief part of this process being formed by an upward extension of the body.

The upper epiphysis joins the body about the sixteenth, the lower about the twentieth year.

Clinical significance

Fractures

Specific fracture types of the ulna include:

- Monteggia fracture - a fracture of the proximal third of the ulna with the dislocation of the head of the radius

- Hume fracture - a fracture of the olecranon with an associated anterior dislocation of the radial head

In other animals

In four-legged animals, the radius is the main load-bearing bone of the lower forelimb, and the ulna is important primarily for muscular attachment. In many mammals, the ulna is partially or wholly fused with the radius, and may therefore not exist as a separate bone. However, even in extreme cases of fusion, such as in horses, the olecranon process is still present, albeit as a projection from the upper radius.[4]

Gallery

-

Position of ulna (shown in red). Animation

-

Right posterior human radius and ulna

-

Human arm bones diagram

-

Bones of left forearm. Anterior aspect.

-

The radius and ulna of the left forearm, posterior surface.

-

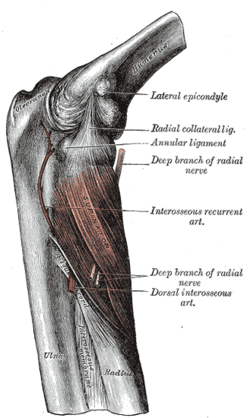

Left elbow-joint, showing anterior and ulnar collateral ligaments.

-

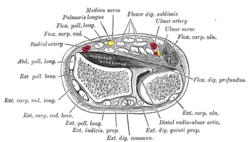

Cross-section through the middle of the forearm.

-

The Supinator.

-

Transverse section across distal ends of radius and ulna.

-

.jpg)

Muscles of upper limb.Cross section.

-

Wrist joint. Deep dissection.Anterior, palmar, view.

-

.jpg)

Elbow joint. Deep dissection. Anterior view.

-

Elbow joint. Deep dissection. Posterior view.

-

Elbow joint. Deep dissection. Posterior view.

See also

- This article uses anatomical terminology; for an overview, see anatomical terminology.

- Bone terminology

- Terms for anatomical location

- Body of ulna

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ↑ OED 2nd edition, 1989.

- ↑ Entry "ulna" in Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary.

- ↑ http://www.innerbody.com/image_skelfov/skel21_new.html

- ↑ Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. p. 200. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ulna. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||