Ukrainian independence referendum, 1991

| Ukrainian independence referendum Sunday, 1 December 1991 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you support the Act of Declaration of Independence of Ukraine? | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Note: Yes results in yellow color. Saturation of colour denotes strength of vote | ||||||||||||||||||||||

A referendum on the Act of Declaration of Independence was held in Ukraine on 1 December 1991.[1] A majority of 92.3% of voters approved the declaration of independence made by the Verkhovna Rada on 24 August 1991.

The referendum

Voters were asked "Do you support the Act of Declaration of Independence of Ukraine?"[2] The text of the Declaration was included as a preamble to the question. The referendum was called by the Parliament of Ukraine to confirm the Act of Independence, which was adopted by the Parliament on 24 August 1991.[3] Citizens of Ukraine expressed overwhelming support for independence. In the referendum, 31,891,742 registered voters (or 84.18% of the electorate) took part, and among them 28,804,071 (or 92.3%) voted "Yes".[2]

On the same day, a presidential election took place. All six candidates campaigned in favour of a "Yes" vote in the independence referendum. Leonid Kravchuk, the parliament chairman and de facto head of state, was elected to serve as the first President of Ukraine.[4]

From 2 December 1991 on Ukraine was globally recognized as an independent state (by other countries).[5] That day the President of the Russian SFSR Boris Yeltsin did the same.[6] In a telegram of congratulations President of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev sent to Kravchuk soon after the referendum, Gorbachev included his hopes for close Ukrainian cooperation and understanding in "the formation of a union of sovereign states".[7]

Ukraine was the second-most powerful republic in the Soviet Union both economically and politically (behind only Russia), and its secession ended any realistic chance of Gorbachev keeping the Soviet Union together. By December 1991 all former Soviet Republics except the RSFSR[8] and the Kazakh SSR[8] had also proclaimed themselves independent.[9] A week after his election, Kravchuk joined with Yeltsin and Belarusian leader Stanislau Shushkevich in signing the Belavezha Accords, which declared that the Soviet Union had ceased to exist.[10] The Soviet Union officially dissolved on December 26.[11]

Results

Ukrainian media had converted en masse to the independence ideal – this resulted in 63% support for the "Yes" campaign in September 1991 that grew to 77% in the first week of October 1991 and 88% by mid-November 1991.[12]

55% of the ethnic Russians in Ukraine voted for independence.[13]

| Choice | Votes | % |

|---|---|---|

| For | 28,804,071 | 92.3 |

| Against | 2,417,554 | 7.7 |

| Invalid/blank votes | 670,117 | – |

| Total | 31,891,742 | 100 |

| Registered voters/turnout | 37,885,555 | 84.2 |

| Source: Nohlen & Stöver | ||

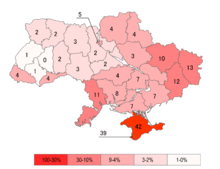

By region

The Act of Independence was supported by a majority of voters in each of the 27 administrative regions of Ukraine: 24 Oblasts, 1 Autonomous Republic, and 2 Special Municipalities (Kiev City and Sevastopol City).[4] Voter turnout was lowest in Eastern and Southern Ukraine.[12] Calculating the "yes"-votes as a percentage of the total electorate reveals a lower percentage of all possible voters in Kharkiv, Luhansk, Donetsk, and Odessa Oblasts and Crimea supported Ukrainian independence than in the rest of the country.[12]

| Subdivision | Voted "Yes" %[4] | Voted "Yes" % of total electorate[14] |

|---|---|---|

| Crimean ASSR | 54.19 | 37 (with a 60% turnout of voters in all Crimea[15]) |

| Cherkasy Oblast | 96.03 | 87 |

| Chernihiv Oblast | 93.74 | 85 |

| Chernivtsi Oblast | 92.78 | 81 |

| Dnipropetrovsk Oblast | 90.36 | 74 |

| Donetsk Oblast | 83.90 | 64 |

| Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast | 98.42 | 94 |

| Kharkiv Oblast | 86.33 | 65 |

| Kherson Oblast | 90.13 | 75 |

| Khmelnytskyi Oblast | 96.30 | 90 |

| Kiev Oblast | 95.52 | 84 |

| Kirovohrad Oblast | 93.88 | 83 |

| Luhansk Oblast | 83.86 | 68 |

| Lviv Oblast | 97.46 | 93 |

| Mykolayiv Oblast | 89.45 | 75 |

| Odessa Oblast | 85.38 | 64 |

| Poltava Oblast | 94.93 | 87 |

| Rivne Oblast | 95.96 | 89 |

| Sumy Oblast | 92.61 | 82 |

| Ternopil Oblast | 98.67 | 96 |

| Vinnytsia Oblast | 95.43 | 87 |

| Volyn Oblast | 96.32 | 90 |

| Zakarpattia Oblast | 92.59 | 77 |

| Zaporizhzhia Oblast | 90.66 | 73 |

| Zhytomyr Oblast | 95.06 | 86 |

| Kiev City | 92.87 | 75 |

| Sevastopol City | 57.07 | 40[15] (with a 60% turnout of voters in all Crimea[15]) |

| National Total | 90.32 | 76[16] |

See also

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Ukraine |

|

Executive

|

|

|

Judiciary

|

|

Local government

|

|

|

See also

|

|

Politics portal |

References

- ↑ Nohlen, D & Stöver, P (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, p1976 ISBN 9783832956097

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Nohlen & Stöver, p1985

- ↑ Historic vote for independence, The Ukrainian Weekly (1 September 1991)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Independence – over 90% vote yes in referendum; Kravchuk elected president of Ukraine, The Ukrainian Weekly (8 December 1991)

- ↑ Ukraine and Russia: The Post-Soviet Transition by Roman Solchanyk, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2000, ISBN 0742510182 (page 100)

Canadian Yearbook of International Law, Vol 30, 1992, University of British Columbia Press, 1993, ISBN 9780774804387 (page 371)

Russia, Ukraine, and the Breakup of the Soviet Union by Roman Szporluk, Hoover Institution Press, 2000, ISBN 0817995420 (page 355 - ↑ Russia's Revolution from Above, 1985-2000: Reform, Transition, and Revolution in the Fall of the Soviet Communist Regime by Gordon M. Hahn, Transaction Publishers, 2001, ISBN 0765800497 (page 482)

A Guide to the United States' History of Recognition, Diplomatic, and Consular Relations, by Country, since 1776: Ukraine, Office of the Historian

The Limited Partnership: Building a Russian-US Security Community by James E. Goodby and Benoit Morel, Oxford University Press, 1993, ISBN 0198291612 (page 48)

Ukrainian Independence, Worldwide News Ukraine - ↑ NEWSBRIEFS FROM UKRAINE, The Ukrainian Weekly (8 December 1991)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Russia's New Politics: The Management of a Postcommunist Society by Stephen K. White, Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 0521587379 (page 240)

- ↑ Citizens in the Making in Post-Soviet States by Olena Nikolayenko, Routledge, 2001, ISBN 0415596041 (page 101)

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of the Russian Federation by Robert A. Saunders & Vlad Strukov, Scarecrow Press, 2010, ISBN 0810854759 (page 75)

- ↑ Turning Points - Actual and Alternate Histories: The Reagan Era from the Iran Crisis to Kosovo by Rodney P. Carlisle and J. Geoffrey Golson, ABC-CLIO, 2007, ISBN 1851098852 (page 111)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Ukrainian Nationalism in the 1990s: A Minority Faith by Andrew Wilson, Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 0521574579 (page 128)

- ↑ The Return: Russia's Journey from Gorbachev to Medvedev by Daniel Treisman, Free Press, 2012, ISBN 1416560726 (page 178)

- ↑ Ukrainian Nationalism in the 1990s: A Minority Faith by Andrew Wilson, Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 0521574579 (page 129)

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Russians in the Former Soviet Republics by Pål Kolstø, Indiana University Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0-253-32917-2 (page 191)

Ukraine and Russia:Representations of the Past by Serhii Plokhy, University of Toronto Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-8020-9327-1 (page 184) - ↑ Post-Communist Ukraine by Bohdan Harasymiw, Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, 2002, ISBN 1895571448

External links

- "Law of Ukraine N 1660-XII on organization of referendum" (in Ukrainian). 1991-10-11.

- "Law of Ukraine N 1661-XII on text for referendum" (in Ukrainian). 1991-10-11.

- "The funeral of the empire", Leonid Kravchuk, Zerkalo Nedeli (Mirror Weekly), August 23 – September 1, 2001. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- "Confide in people," Dr. Stanislav Kulchytsky, Zerkalo Nedeli (Mirror Weekly), December 1–7, 2001. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||