Uganda

| Republic of Uganda Jamhuri ya Uganda

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: "For God and My Country" | ||||||

| Anthem: "Oh Uganda, Land of Beauty" |

||||||

Location of Uganda (dark blue) – in Africa (light blue & dark grey) |

||||||

| Capital and largest city | Kampala | |||||

| Official languages | English, Swahili | |||||

| Vernacular languages |

|

|||||

| Ethnic groups (2002) | ||||||

| Demonym | Ugandan[2] | |||||

| Government | Dominant-party semi-presidential republic[2] | |||||

| - | President | Yoweri Museveni | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Ruhakana Rugunda | ||||

| Legislature | Parliament | |||||

| Independence | ||||||

| - | from the United Kingdom | 9 October 1962 | ||||

| - | Current constitution | 8 October 1995 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 241,038 km2 (81st) 93,065 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 15.39 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | estimate | 37,873,253[2] (35th) | ||||

| - | 2013 census | 36,824,000 | ||||

| - | Density | 137.1/km2 (80th) 355.2/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2012 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $50.439 billion[3] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $1,414[3] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2012 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $21.002 billion[3] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $589[3] | ||||

| Gini (2009) | 44.11[4] medium |

|||||

| HDI (2013) | low · 164th |

|||||

| Currency | Ugandan shilling (UGX) | |||||

| Time zone | EAT | |||||

| Drives on the | left | |||||

| Calling code | +256a | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | UG | |||||

| Internet TLD | .ug | |||||

| a. | +006 from Kenya and Tanzania. | |||||

Uganda (/juːˈɡændə/ yew-GAN-də or /juːˈɡɑːndə/ yew-GAHN-də), officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the southwest by Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. Uganda is the world's second most populous landlocked country after Ethiopia. The southern part of the country includes a substantial portion of Lake Victoria, shared with Kenya and Tanzania, situating the country in the African Great Lakes region. Uganda also lies within the Nile basin, and has a varied but generally equatorial climate.

Uganda takes its name from the Buganda kingdom, which encompasses a large portion of the south of the country including the capital Kampala. The people of Uganda were hunter-gatherers until 1,700 to 2,300 years ago, when Bantu-speaking populations migrated to the southern parts of the country.

Beginning in the late 1800s, the area was ruled as a protectorate by the British, who established administrative law across the territory. Uganda gained independence from Britain on 9 October 1962. The period since then has been marked by intermittent conflicts, most recently a lengthy civil war against the Lord's Resistance Army, which has caused tens of thousands of casualties and displaced more than a million people.

The official languages are Swahili and English. Luganda, a central language, is widely spoken across the country, and multiple other languages are also spoken including Runyoro, Runyankole Rukiga, Langi and many others. The current President of Uganda is Yoweri Kaguta Museveni who came to power in a coup in 1986.

History

The Ugandans were hunter-gatherers until 1,700 to 2,300 years ago. Bantu-speaking populations, who were probably from central Africa, migrated to the southern parts of the country.[6][7] These groups brought and developed ironworking skills and new ideas of social and political organisation. The Empire of Kitara covered most of the great lakes area, from Lake Albert, Lake Tanganyika, Lake Victoria, to Lake Kyoga. Its leadership headquarters were mainly in what became Ankole, believed to have been run by the Bachwezi dynasty in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. They may have followed a semi-legendary dynasty known as the Batembuzi. Bunyoro-Kitara is claimed as the antecedent of later kingdoms; Buganda, Toro, Ankole and Busoga.[8]

Nilotic people, including Luo and Ateker, entered the area from the north, probably beginning about A.D. 120. They were cattle herders and subsistence farmers who settled mainly in the northern and eastern parts of the country. The Nilotic Luo invasion is believed to have led to the collapse of the Chwezi Empire. The twins Rukidi Mpuuga and Kato Kintu are believed to be the first kings of Bunyonro and Buganda after the Chwezi Empire collapsed, creating the Babiito and Bambejja Dynasty. Some Luo invaded the area of Bunyoro and assimilated with the Bantu there, establishing the Babiito dynasty of the current Omukama (ruler) of Bunyoro-Kitara.[9]

Luo migration continued until the 16th century, with some Luo settling amid Bantu people in Eastern Uganda, with others proceeding to the eastern shores of Lake Victoria in Kenya and Tanzania. The Ateker (Karimojong and Iteso) settled in the northeastern and eastern parts of the country, and some fused with the Luo in the area north of Lake Kyoga.

Arab traders moved inland from the Indian Ocean coast of East Africa in the 1830s. They were followed in the 1860s by British explorers searching for the source of the Nile.[10]:151 Protestant missionaries entered the country in 1877, followed by Catholic missionaries in 1879,[11] a situation which gave rise to the death of the Uganda Martyrs. The United Kingdom placed the area under the charter of the British East Africa Company in 1888, and ruled it as a protectorate from 1894.

In the 1890s, 32,000 labourers from British India were recruited to East Africa under indentured labour contracts to work on the construction of the Uganda Railway. Most of the surviving Indians returned home, but 6,724 decided to remain in East Africa after the line's completion. British naval ships unknowingly carried rats that contained the bubonic plague. These rats spread the disease throughout Uganda and the following disaster became known as the Black Plague. Over one million people died by the early 1900s.[12]

As several other territories and chiefdoms were integrated, the final protectorate called Uganda took shape in 1914. From 1900 to 1920, a sleeping sickness epidemic killed more than 250,000 people.[13]

Independence (1962)

Uganda gained independence from Britain in 1962, maintaining its Commonwealth membership. The first post-independence election, held in 1962, was won by an alliance between the Uganda People's Congress (UPC) and Kabaka Yekka (KY). UPC and KY formed the first post-independence government with Milton Obote as executive Prime Minister, the Buganda Kabaka (King) Edward Muteesa II holding the largely ceremonial position of President[14][15] and William Wilberforce Nadiope, the Kyabazinga (paramount chief) of Busoga, as Vice-President.

In 1966, following a power struggle between the Obote-led government and King Muteesa, the UPC-dominated Parliament changed the constitution and removed the ceremonial president and vice-president. In 1967, a new constitution proclaimed Uganda a republic and abolished the traditional kingdoms. Without first calling elections, Obote was declared the executive President.[16]

After a military coup in 1971, Obote was deposed from power and the dictator Idi Amin seized control of the country. Amin ruled Uganda with the military for the next eight years[17] and carried out mass killings within the country to maintain his rule. An estimated 300,000 Ugandans lost their lives at the hands of his regime, many of them in the north, which he associated with Obote's loyalists.[18] Aside from his brutalities, he forcibly removed the entrepreneurial Indian minority from Uganda, which left the country's economy in ruins.[19] Amin's atrocities were graphically accounted in the 1977 book, A State of Blood, written by one of his former ministers after he fled the country.

In 1972, with the so-called "Africanization" of Uganda, 580,000 Asian Indians with British passports left Uganda. Approximately 7000 were invited to settle in Canada; however only a limited number accepted the offer, and the 2006 census reported 3300 people of Ugandan origin in Canada. Given the variety of skills and professional background they brought with them, coupled with their initiative and enterprising attitudes, most Ugandans have made steady socioeconomic progress in Canada. They have settled primarily in Ontario (Toronto), BC and Québec.

Amin's reign was ended after the Uganda-Tanzania War in 1979, in which Tanzanian forces aided by Ugandan exiles invaded Uganda. This led to the return of Obote, who was deposed again in 1985 by General Tito Okello. Okello ruled for six months until he was deposed. This occurred after the so-called "bush war" by the National Resistance Army (NRA) operating under the leadership of the current president, Yoweri Museveni, and various rebel groups, including the Federal Democratic Movement of Andrew Kayiira, and another belonging to John Nkwaanga. During the Bush War the army carried out mass killings of non-combatants.[20]

Museveni has been in power since 1986. In the mid- to late 1990s, he was lauded by the West as part of a new generation of African leaders.[21] As president, he has led Uganda in involvement in the civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and other conflicts in the Great Lakes region. He has struggled for years in the civil war against the Lord's Resistance Army, which has been guilty of numerous crimes against humanity, including child slavery and mass murder. Conflict in northern Uganda has killed thousands and displaced millions.[22]

Geography

The country is located on the East African plateau, lying mostly between latitudes 4°N and 2°S (a small area is north of 4°), and longitudes 29° and 35°E. It averages about 1,100 metres (3,609 ft) above sea level, and this slopes very steadily downwards to the Sudanese Plain to the north. However, much of the south is poorly drained, while the centre is dominated by Lake Kyoga, which is also surrounded by extensive marshy areas.

Uganda lies almost completely within the Nile basin. The Victoria Nile drains from Lake Victoria into Lake Kyoga and thence into Lake Albert on the Congolese border. It then runs northwards into South Sudan. One small area on the eastern edge of Uganda is drained by the Turkwel River, part of the internal drainage basin of Lake Turkana.

Lake Kyoga serves as a rough boundary between Bantu speakers in the south and Nilotic and Central Sudanic language speakers in the north. Despite the division between north and south in political affairs, this linguistic boundary runs roughly from northwest to southeast, near the course of the Nile. However, many Ugandans live among people who speak different languages, especially in rural areas. Some sources describe regional variation in terms of physical characteristics, clothing, bodily adornment, and mannerisms, but others claim that those differences are disappearing.

Although generally equatorial, the climate is not uniform as large variations in the altitude modify the climate. Southern Uganda is wetter with rain generally spread throughout the year. At Entebbe on the northern shore of Lake Victoria, most rain falls from March to June and in the November/December period. Further to the north a dry season gradually emerges; at Gulu about 120 km (75 mi) from the South Sudanese border, November to February is much drier than the rest of the year.

The northeastern Karamoja region has the driest climate and is prone to droughts in some years. Rwenzori, a snowy peaked mountainous region on the southwest border with Congo (DRC), receives heavy rain all year.

The south of the country is heavily influenced by one of the world's biggest lakes, Lake Victoria, which contains many islands. It prevents temperatures from varying significantly and increases cloudiness and rainfall. Most important cities are located in the south, near Lake Victoria, including the capital Kampala and the nearby city of Entebbe.

Although landlocked, Uganda contains many large lakes; besides Lake Victoria and Lake Kyoga, there are Lake Albert, Lake Edward and the smaller Lake George.

Environment and conservation

Uganda has 60 protected areas, including ten national parks: Bwindi Impenetrable National Park and Rwenzori Mountains National Park (both UNESCO World Heritage Sites[23]), Kibale National Park, Kidepo Valley National Park, Lake Mburo National Park, Mgahinga Gorilla National Park, Mount Elgon National Park, Kenya National Park, Murchison Falls National Park, Queen Elizabeth National Park, and Semuliki National Park.

Government and politics

The President of Uganda, currently Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, is both head of state and head of government. The President appoints a Vice-President, currently Edward Ssekandi, and a prime minister, currently Ruhakana Rugunda, who aid him in governing. The parliament is formed by the National Assembly, which has 332 members. 104 of these members are nominated by interest groups, including women and the army. The remaining members are elected for five-year terms during general elections.[24]

In the mid-to-late 1990s, Museveni was lauded by the West as part of a new generation of African leaders. His presidency has been marred, however, by invading and occupying Congo during the Second Congo War (the war in the Democratic Republic of Congo which has resulted in an estimated 5.4 million deaths since 1998) and other conflicts in the Great Lakes region. Recent developments, including the abolition of presidential term limits before the 2006 elections, Museveni's confirmation of the Public Order Management Bill – a bill which severely limits freedom of assembly – media censorship and the persecution of democratic opposition (i.e. general intimidation of voters by security forces; arresting opposition candidates; extrajudicial killings) have attracted concern from domestic and foreign commentators. Most recently, indicators of an alleged succession to the President's son, Muhoozi Kainerugaba, have increased tensions.[25][26][27][28]

Political parties in Uganda were restricted in their activities beginning in 1986, in a measure ostensibly designed to reduce sectarian violence. In the non-party "Movement" system instituted by Museveni, political parties continued to exist, but they could only operate a headquarters office. They could not open branches, hold rallies, or field candidates directly (although electoral candidates could belong to political parties). A constitutional referendum cancelled this nineteen-year ban on multi-party politics in July 2005. Additionally, the constitutional term limit for the presidency was changed from the previous two-term limit, to enable the current president to continue in active politics.

Presidential elections were held in February 2006. Yoweri Museveni ran against several candidates, the most prominent of them being Dr. Kizza Besigye.

On Sunday, 20 February 2011, the Uganda Electoral Commission declared the 24-year reigning president Yoweri Kaguta Museveni the winning candidate of the 2011 elections that were held on 18 February 2011. The opposition were, however, not satisfied with the results, condemning them as full of sham and rigging. According to the results released, Museveni won with 68% of the votes, easily topping his nearest challenger Kizza Besigye. Besigye, who was formerly Museveni's physician, told reporters that he and his supporters 'downrightly snub' the outcome as well as the unremitting rule of Museveni or any person he may appoint. Besigye added that the rigged elections would definitely lead to an illegitimate lead and that it is up to Ugandans to critically analyse this.

The EU Election Observation Mission reported on improvements and flaws of the Ugandan electoral process: "The electoral campaign and polling day were conducted in a peaceful manner [...] However, the electoral process was marred by avoidable administrative and logistical failures that led to an unacceptable number of Ugandan citizens being disfranchised."[29] Since August 2012, hacktivist group Anonymous has threatened Ugandan officials and hacked official government websites over its anti-gay bills.[30] Some international donors have threatened to cut financial aid to the country if anti-gay bills continue.[31]

Museveni is expected to head Uganda until the next elections anticipated to be held in 2016.

Uganda is rated among countries perceived as very corrupt by Transparency International. It is rated at 29 on a scale from 0 (perceived as most corrupt) to 100 (perceived as clean).[32]

According to the US State Department's 2012 Human Rights Report on Uganda, "The World Bank's most recent Worldwide Governance Indicators reflected corruption was a severe problem" and that "the country annually loses 768.9 billion shillings ($286 million) to corruption."[27] Understandably, Uganda was ranked 130th out of 176 nations on the Corruption Perceptions Index.[33] Ugandan parliamentarians in 2014 were earning 60 times that being earned by most state employees and they were seeking a major increase. This was causing widespread criticism and protests, including the smuggling of two piglets into the parliament in June 2014 to highlight corruption amongst members of parliament. The protesters, who were arrested, were using the word "MPigs" to highlight their grievance.[34] A specific scandal, which had significant international consequences and highlighted the presence of corruption in high-level government offices, was the embezzlement of $12.6 mil in donor funds from the Office of the Prime Minister in 2012. These funds were "earmarked as crucial support for rebuilding northern Uganda, ravaged by a 20-year war, and Karamoja, Uganda's poorest region." This scandal prompted the EU, The UK, Germany, Denmark, Ireland and Norway to suspend aid.[35] What may compound this problem – as it does in many developing nations (Resource curse) – is the availability of oil. Widespread grand and petty corruption involving public officials and political patronage systems have also seriously affect the investment climate in Uganda. One of the high corruption risk areas is the public procurement in which non-transparent under-the-table cash payments are often demanded from procurement officers.[36]

The Petroleum Bill – passed by Ugandan Parliament in 2012 – which was touted by the NRM as bringing transparency to the oil sector has, failed to please domestic and international political commentators and economists. For instance, Angelo Izama, a Ugandan energy analyst at the US-based Open Society Foundation said the new law was tantamount to "handing over an ATM (cash) machine" to Museveni and his regime.[37] According to Global Witness, an international law NGO, Uganda now has "oil reserves that have the potential to double the government's revenue within six to ten years, worth an estimated US$2.4bn per year."[38]

Other contentious bills have been passed by parliament and confirmed by President Museveni during his tenure. For example, The Non Governmental Organizations (Amendment) Act, passed in 2006, has stifled the productivity of NGOs through erecting barriers to entry, activity, funding and assembly within the sector. Burdensome and corrupt registration procedures (i.e. requiring recommendations from government officials; annual re-registration), unreasonable regulation of operations (i.e. requiring government notification prior to making contact with individuals in NGO's area of interest), and the precondition that all foreign funds be passed through the Bank of Uganda, among others things, are severely limiting the output of the NGO sector. Furthermore, the sector's freedom of speech has been continually infringed upon through the use of intimidation, and the recent Public Order Management Bill (severely limiting freedom of assembly) will only add to the government's stockpile of ammunition.[39]

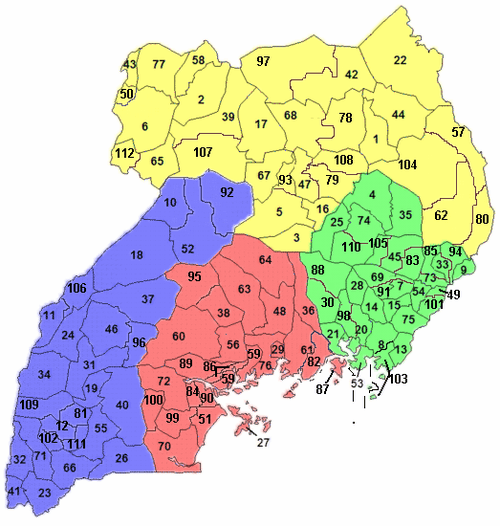

Political divisions

Uganda is divided into districts, spread across four administrative regions: Northern, Eastern, Central (Kingdom of Buganda) and Western. The districts are subdivided into counties. A number of districts have been added in the past few years, and eight others were added on 1 July 2006 plus others added in 2010. There are now over 100 districts.[40] Most districts are named after their main commercial and administrative towns. Each district is divided into sub-districts, counties, sub-counties, parishes and villages. Political subdivisions in Uganda are officially served and united by the Uganda Local Governments Association (ULGA), a voluntary and non-profit body which also serves as a forum for support and guidance for Ugandan sub-national governments.[41]

Parallel with the state administration, five traditional Bantu kingdoms have remained, enjoying some degrees of mainly cultural autonomy. The kingdoms are Toro, Busoga, Bunyoro, Buganda and Rwenzururu. Furthermore, some groups attempt to restore Ankole as one of the officially recognised traditional kingdoms, to no avail yet.[42] Several other kingdoms and chiefdoms are officially recognized by the government, including the union of Alur chiefdoms, the Iteso paramount chieftancy, the paramount chieftaincy of Lango and the Padhola state. [43]

Foreign relations and military

In Uganda, the Uganda People's Defence Force serves as the military. The number of military personnel in Uganda is estimated at 45,000 soldiers on active duty. The Uganda army is involved in several peacekeeping and combat missions in the region, with commentators noting that only the United States Armed Forces is currently deployed in more countries. Uganda has soldiers deployed in the northern and eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, in the Central African Republic, Somalia, and South Sudan.[44]

Human rights

There are many areas which continue to attract concern when it comes to human rights in Uganda.

Conflict in the northern parts of the country continues to generate reports of abuses by both the rebel Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), led by Joseph Kony, and the Ugandan Army. A UN official accused the LRA in February 2009 of "appalling brutality" in the Democratic Republic of Congo.[45]

The number of internally displaced persons is estimated at 1.4 million. Torture continues to be a widespread practice amongst security organisations. Attacks on political freedom in the country, including the arrest and beating of opposition members of parliament, have led to international criticism, culminating in May 2005 in a decision by the British government to withhold part of its aid to the country. The arrest of the main opposition leader Kizza Besigye and the siege of the High Court during a hearing of Besigye's case by heavily armed security forces – before the February 2006 elections – led to condemnation.[46]

Child labour is common in Uganda. Many child workers are active in agriculture.[47] Children who work on tobacco farms in Uganda are exposed to health hazards.[47] Child domestic servants in Uganda risk sexual abuse.[47] Trafficking of children occurs.[47] Slavery and forced labour are prohibited by the Ugandan constitution.[47]

The US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants reported several violations of refugee rights in 2007, including forcible deportations by the Ugandan government and violence directed against refugees.[48]

Torture and extrajudicial killings have been a pervasive problem in Uganda in recent years. For instance, according to a 2012 US State Department report, "the African Center for Treatment and Rehabilitation for Torture Victims registered 170 allegations of torture against police, 214 against the UPDF, one against military police, 23 against the Special Investigations Unit, 361 against unspecified security personnel, and 24 against prison officials" between January and September 2012.[27]

In September 2009 Museveni refused Kabaka Muwenda Mutebi, the Baganda King, permission to visit some areas of Buganda Kingdom, particularly the Kayunga district. Riots occurred and over 40 people were killed while others remain imprisoned to this date. Furthermore, 9 more people were killed during the April 2011 "Walk to Work" demonstrations. According to the Humans Rights Watch 2013 World Report on Uganda, the government has failed to investigate the killings associated with both of these events.[49]

LGBT rights

As of January 2014, homosexuality is illegal in Uganda and carries a minimum sentence of two years in prison and a maximum of life. Sodomy laws from the British colonial era are still on the books, and there is a strong social bias against homosexuality. Gays and lesbians face discrimination and harassment at the hands of the media, police, teachers, and other groups. In 2007, a Ugandan newspaper, The Red Pepper, published a list of allegedly gay men, many of whom suffered harassment as a result.[50] Also on 9 October 2010, the Ugandan newspaper Rolling Stone published a front page article titled "100 Pictures of Uganda's Top Homos Leak" that listed the names, addresses, and photographs of 100 homosexuals alongside a yellow banner that read "Hang Them".[51]

The paper also alleged that homosexuals aimed to recruit Ugandan children. This publication attracted international attention and criticism from human rights organisations, such as Amnesty International,[52] No Peace Without Justice[53] and the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association.[54] According to gay rights activists, many Ugandans have been attacked since the publication.[55] On 27 January 2011, gay rights activist David Kato was murdered.[56] Kato was on Rolling Stone's hit list. Also a number of other gays and lesbians are missing and are believed to have been murdered.

In 2009, the Ugandan parliament considered an Anti-Homosexuality Bill which would have broadened the criminalisation of homosexuality by introducing the death penalty for people who have previous convictions, or are HIV-positive, and engage in same-sex sexual acts. The bill also included provisions for Ugandans who engage in same-sex sexual relations outside of Uganda, asserting that they may be extradited back to Uganda for punishment, and included penalties for individuals, companies, media organisations, or non-governmental organisations that support legal protection for homosexuality or sodomy. The private member's bill was submitted by MP David Bahati in Uganda on 14 October 2009, and was believed to have had widespread support in the Uganda parliament.[57] The hacktivist group Anonymous hacked into Ugandan government websites in protest of the bill.[58] Debate of the bill was delayed in response to global condemnation but was eventually passed on 20 December 2013 and signed into law by President Yoweri Museveni on 24 February 2014. The death penalty was dropped in the final legislation and replaced by life imprisonment. The law was widely condemned by the international community. Denmark, Netherlands and Sweden said they would withhold aid. The World Bank on 28 February 2014 said it would postpone a $90 million loan, while the United States said it was reviewing ties with Uganda.[59]

Economy and infrastructure

The Bank of Uganda is the Central bank of Uganda and handles monetary policy along with the printing of the Ugandan shilling.[60]

Uganda's economy generates income from annual exports that include coffee ($466.6 million), tea ($72.1 million), fish ($136.2 million), and other products.[61] The country has commenced economic reforms and growth has been robust. In 2008, Uganda recorded 7% growth despite the global downturn and regional instability.[62] Uganda's struggle to achieve their economic status was primarily due to decades of wars and corruption resulting in the nation being considered one of the poorest countries in the world.

Uganda has substantial natural resources, including fertile soils, regular rainfall, and sizeable mineral deposits of copper and cobalt. The country has largely untapped reserves of both crude oil and natural gas.[63] While agriculture accounted for 56% of the economy in 1986, with coffee as its main export, it has now been surpassed by the services sector, which accounted for 52% of GDP in 2007.[64] In the 1950s the British Colonial regime encouraged some 500,000 subsistence farmers to join co-operatives.[65] Since 1986, the government (with the support of foreign countries and international agencies) has acted to rehabilitate an economy devastated during the regime of Idi Amin and the subsequent civil war.[2] Inflation ran at 240% in 1987 and 42% in June 1992, and was 5.1% in 2003.

.jpg)

Between 1990 and 2001, the economy grew because of continued investment in the rehabilitation of infrastructure, improved incentives for production and exports, reduced inflation and gradually improved domestic security. Ugandan involvement in the war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, corruption within the government, and slippage in the government's determination to press reforms raise doubts about the continuation of strong growth.

In 2000, Uganda was included in the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) debt relief initiative worth $1.3 billion and Paris Club debt relief worth $145 million. These amounts combined with the original HIPC debt relief added up to about $2 billion. In 2012, the World Bank still listed Uganda as on the HIPC list. Growth for 2001–2002 was solid despite continued decline in the price of coffee, Uganda's principal export.[2] According to IMF statistics, in 2004 Uganda's GDP per capita reached $300, a much higher level than in the 1980s but still at half the Sub-Saharan African average income of $600 per year. Total GDP crossed the 8 billion dollar mark in the same year.

Economic growth has not always led to poverty reduction. Despite an average annual growth of 2.5% between 2000 and 2003, poverty levels increased by 3.8% during that time.[66] This has highlighted the importance of avoiding jobless growth and is part of the rising awareness in development circles of the need for equitable growth not just in Uganda, but across the developing world.[66]

With the Uganda securities exchanges established in 1996, several equities have been listed. The Government has used the stock market as an avenue for privatisation. All Government treasury issues are listed on the securities exchange. The Capital Markets Authority has licensed 18 brokers, asset managers and investment advisors including names like: African Alliance Investment Bank, Baroda Capital Markets Uganda Limited, Crane Financial Services Uganda Limited, Crested Stocks and Securities Limited, Dyer & Blair Investment Bank, Equity Stock Brokers Uganda Limited, Renaissance Capital Investment Bank and UAP Financial Services Limited.[67] As one of the ways of increasing formal domestic savings, pension sector reform is the centre of attention (2007).[68][69]

Uganda traditionally depends on Kenya for access to the Indian Ocean port of Mombasa. Recently, efforts have intensified to establish a second access route to the sea via the lakeside ports of Bukasa in Uganda and Musoma in Tanzania, connected by railway to Arusha in the Tanzanian interior and to the port of Tanga on the Indian Ocean.[70] Uganda is a member of the East African Community and a potential member of the planned East African Federation.

Uganda has a large diaspora, residing mainly in the United States and the United Kingdom. This diaspora has contributed enormously to Uganda's economic growth through remittances and other investments (especially property). According to the World Bank, in 2010/2011 Uganda got $694 million in remittances from Ugandans abroad, the highest foreign exchange earner for the country.[71] Uganda also serves as an economic hub for a number of neighbouring countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo,[72] South Sudan[73] and Rwanda.[74]

Poverty

Uganda is one of the poorest nations in the world, with 37.7% of the population living on less than $1.25 a day.[75] Despite making enormous progress in reducing the countrywide poverty incidence from 56% of the population in 1992 to 31% in 2005,[76] poverty remains deep-rooted in the country's rural areas, which are home to more than 85 per cent of Ugandans.

People in rural areas of Uganda depend on farming as the main source of income and 90 per cent of all rural women work in the agricultural sector.[77] In addition to agricultural work, rural women also have the responsibility of caretaking within their families. The average Ugandan woman spends 9 hours a day on domestic tasks, such as preparing food and clothing, fetching water and firewood, and caring for the elderly, the sick as well as orphans. As such, women on average work longer hours than men, between 12 and 18 hours per day, with a mean of 15 hours, as compared to men, who work between 8 and 10 hours a day.[78]

To supplement their income, rural women may engage in small-scale entrepreneurial activities such as rearing and selling local breeds of animals. Nonetheless, because of their heavy workload, they have little time for these income-generating activities. The poor cannot support their children at school and in most cases, girls drop out of school to help out in domestic work or to get married. Other girls engage in sex work. As a result, young women tend to have older and more sexually experienced partners and this puts women at a disproportionate risk of getting affected by HIV, accounting for about 57 per cent of all adults living with HIV.[79]

Maternal health in rural Uganda lags behind national policy targets and the Millennium Development Goals, with geographical inaccessibility, lack of transport and financial burdens identified as key demand-side constraints to accessing maternal health services;[80] as such, interventions like intermediate transport mechanisms have been adopted as a means to improve women's access to maternal health care services in rural regions of the country.[81]

Gender inequality is a main hindrance to reducing women's poverty. Women submit to an overall lower social status than men. For many women, this reduces their power to act independently, participate in community life, become educated and escape reliance upon abusive men.[82]

Uganda has realised that the lack of women's rights is part of the major causes of poverty in the country. Results of the 1998/99 Uganda Participatory Poverty Assessment (UPPAP) – on which the revised Poverty Eradication Action Plan (PEAP) is based – and the UPPAP2 (2001/2002) demonstrate strong linkage between gender and poverty. Key policies such as the National Gender Policy in 1997 have also been enacted to mainstream gender in the national development process to improve the social, legal/civic, political, economic and cultural conditions of the people, especially of women. Also, the National Action Plan on Women (NAPW) was implemented in 1999 to identify five critical areas for action to advance women's rights: legal and policy framework and leadership; social and economic empowerment of women; reproductive health, rights and responsibilities; girl child education; peace building conflict resolution and freedom from violence.

Communications

There are seven telecommunications companies serving over 17 million subscribers in a population of 32 million. More than 95% of internet connections are made using mobile phones.[83]

By 1 March 2012, 17 million subscribers had registered their SIM cards for mobile phones.[84]

Transport

.jpg)

Uganda's transport infrastructure includes four railway lines, developed by the Uganda Railways Corporation. There are also four airports with paved runways, and 22 unpaved runways. Most roads are paved in the south. However, the far north and the farther away from the main cities (Kampala and Entebbe), the fewer paved roads exist.

The most common methods of public transportation are by minivan taxi (matatu), motorcycle taxi (boda boda), and charter bus.

Charter buses are reserved for long distance travel. Busses leave when full and only stop to let passengers off (rarely on), and for bathroom breaks at pre-determined gas stations along the way. These large busses are generally the fastest mode of transportation, passing all other vehicles on the road with alarming momentum.

Matatus (minivan taxis) are used for medium and long distance travel. These late model Toyota mini-vans are only licensed to carry 14 passengers three to a row, but often sit "four four" (four to a row), or even "five five" in the villages. Taxis leave when full and most drop off and pick up passengers anywhere along their route, with the exception of express taxis. Express taxis fill from the taxi park, charge fare to the final destination up front, and (mostly) don't replace passengers they drop off along the way.

Boda bodas (motorcycle taxis) are used for short distance travel. These 100cc Indian road bikes carry just about anything anywhere within 10 or 15 kilometers for just a few thousand Ugandan shillings. Don't be surprised to see furniture, a family of four, or fifty tied chickens being transported on a boda boda. But be warned, accidents are common as these vehicles are severely underpowered and are bullied to the shoulder of the road by all other vehicles.

Energy

In the 1980s, the majority of energy in Uganda came from charcoal and wood. However, oil was found in the Lake Albert area, totalling an estimated 95,000,000 m3 barrels of crude.[63] Heritage Oil discovered one of the largest crude oil finds in Uganda, and continues operations there.[85]

Education

At the 2002 census, Uganda had a literacy rate of 66.8% (76.8% male and 57.7% female).[2] Public spending on education was at 5.2% of the 2002–2005 GDP.[86] The system of education in Uganda has a structure of 7 years of primary education, 6 years of secondary education (divided into 4 years of lower secondary and 2 years of upper secondary school), and 3 to 5 years of post-secondary education. There are state exams that must be taken at every level of education.

The present system has existed since the early 1960s. Although some primary education is compulsory under law, in many rural communities this is not observed as many families feel they cannot afford costs such as uniforms and equipment. Most major Schools were formerly built and run by Church Organisations, including the Church of Uganda and the Catholic Church on land owned as such. Of late (circa 2013), many privately run and privately built, for-profit Schools, have been established. In primary education, children sit exams at the end of each academic year to discern whether they are to progress to the next class; this leads to some classes which include a large range of Upon completing P7 (The final year of primary education), many children from poorer rural communities will return to their families for subsistence farming. Secondary education is focused mainly in larger cities, with boarding optional. Children are usually presented with an equipment list which they are to obtain at the beginning of their time at secondary school. This list classically includes items such as writing equipment, toilet roll and cleaning brushes, all of which the student must have upon admission to school.

Uganda has both private and public universities. The largest university in Uganda is Makerere University, located outside of Kampala. Milton Obote, former President of Uganda, was an alumnus.

Health

Uganda has been among the rare HIV success stories.[86] Infection rates of 30 per cent of the population in the 1980s fell to 6.4% by the end of 2008.[87] However, there has been a spike in recent years compared to the mid-nineties,[88] especially after a shift in US Aid Policy toward abstinence only campaigns (starting in 2003 with the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief under US President George W. Bush). According to one report by Uganda's Aids commissioner, the number of new HIV infections has almost doubled from 70,000 in 2003 to 130,000 in 2005. Researchers have found that rates of new infection have stabilised as of 2005 due to a variety of factors, including increased condom use and sexual health awareness. Meanwhile, the practice of abstinence was found to have decreased.[89]

The prevalence of female genital mutilation (FGM) is low: according to a 2013 UNICEF report,[90] only 1% of women in Uganda have undergone FGM; and the practice is also illegal in the country.[91]

Life expectancy at birth is estimated to be 53.45 years in 2012.[92] The infant mortality rate is approximately 61 deaths per 1,000 children in 2012.[93] There were 8 physicians per 100,000 persons in the early 2000s.[86] The 2006 Uganda Demographic Health Survey (UDHS) indicates that roughly 6,000 women die each year due to pregnancy-related complications.[94] However, recent pilot studies by Future Health Systems have shown that this rate could be significantly reduced by implementing a voucher scheme for health services and transport to clinics.[95][96]

Uganda's elimination of user fees at state health facilities in 2001 has resulted in an 80% increase in visits; over half of this increase is from the poorest 20% of the population.[97] This policy has been cited as a key factor in helping Uganda achieve its Millennium Development Goals and as an example of the importance of equity in achieving those goals.[66] Despite this policy, many users are denied care if they don't provide their own medical equipment, as happened in the highly publicised case of Jennifer Anguko.[98] Poor communication within hospitals,[99] low satisfaction with health services[100] and distance to health service providers undermine the provision of quality health care to people living in Uganda, and particularly for those in poor and elderly-headed households.[101] The provision of subsidies for poor and rural populations, along with the extension of public private partnerships, have been identified as important provisions to enable vulnerable populations to access health services.[101]

In July 2012, there was Ebola outbreak in the Kibaale District of the country.[102] On 4 October 2012, the Ministry of Health officially declared the end of the Ebola outbreak that killed at least 16 people.[103]

Uganda also has Hospitals such as the Mulago Hospital which was built in 1962.

It was announced by the Health Ministry on 16 August 2013, that three people died in northern Uganda from a suspected outbreak of Congo Crimean Hemorrhagic Fever (CCHF).[104]

Crime and law enforcement

In Uganda, the Allied Democratic Forces is considered a violent rebel force that opposes the Ugandan government. These rebels are an enemy of the Uganda People's Defence Force and are considered an affiliate of Al-Shabaab.[105]

Demographics

.jpg)

The country has very significant overpopulation problems.[106]

Uganda's population has grown from 9.5 million people in 1969 to 34.9 million in 2014.With respect to the last inter-censal period (September 2002), the population increased by 10.6 million people in the past 12 years.[107] Uganda has a very young population; With a median age of 15 years, it is the lowest median age in the world.[2] Uganda has the fifth highest total fertility rate in the world, at 5.97 children born/woman (2014 estimates).[2]

Uganda is home to many different ethnic groups, none of whom forms a majority of the population. The population of Uganda consists of: Baganda 16.9%, Banyakole 9.5%, Basoga 8.4%, Bakiga 6.9%, Iteso 6.4%, Langi 6.1%, Acholi 4.7%, Bagisu 4.6%, Lugbara 4.2%, Banyoro 2.7%, other 29.6%.

There were about 80,000 Indians in Uganda prior to Idi Amin mandating the expulsion of the Ugandan-Asians (mostly of Indian origin) in 1972, which reduced the population to as low as 7,000. However, many Indians returned to Uganda after Amin's fall from power in 1979, and the population is now between 15,000 and 25,000. around 90 percent of the Ugandan Indians reside in Kampala, the capital.[108]

There are around 20,000 white residents in Uganda, mostly from the United Kingdom.

According to the UNHCR, Uganda hosted over 190,000 refugees in 2013. Most of the latter came from neighbouring countries in the African Great Lakes region, namely Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Rwanda and Sudan.[109]

Languages

Around forty different languages are regularly and currently in use in the country. These fall into two main language families: Niger-Congo (Bantu branch) and Nilo-Saharan (Nilotic and Central Sudanic branches). English became the official language of Uganda after independence, and Ugandan English is a local variant dialect. Additionally, all Ugandan schools and universities are required by law to teach in English. Despite this, 72% of Ugandans speak no English, 22% speak at least some English, and 6% speak English fluently.

The most widely spoken local language in Uganda is Luganda, spoken predominantly by the Ganda people (Baganda) in the urban concentrations of Kampala, the capital city, and in towns and localities in the Buganda region of Uganda which encompasses Kampala. The Lusoga and Runyankore-Rukiga languages follow, spoken predominantly in the southeastern and southwestern parts of Uganda respectively.

Swahili, a widely used language throughout the African Great Lakes region, was approved as the country's second official national language in 2005,[110][111] though this is somewhat politically sensitive. English was the only official language until the constitution was amended in 2005. Though Swahili has not been favoured by the Bantu-speaking populations of the south and southwest of the country, it is an important lingua franca in the northern regions. It is also widely used in the police and military forces, which may be a historical result of the disproportionate recruitment of northerners into the security forces during the colonial period. The status of Swahili has thus alternated with the political group in power.[112] For example, Amin, who came from the northwest, declared Swahili to be the national language.[113]

Religion

According to the census of 2002, Christians made up about 84% of Uganda's population.[114] The Roman Catholic Church has the largest number of adherents (41.9%), followed by the Anglican Church of Uganda (35.9%). Evangelical and Pentecostal churches claim the rest of the Christian population. There are a growing number of Presbyterian denominations like the Presbyterian Church in Uganda, the Reformed Presbyterian Church in Uganda and the Evangelical Free Church in Uganda with hundreds of affiliating congregations. The next most reported religion of Uganda is Islam, with Muslims representing 12% of the population.[114]

The Muslim population is primarily Sunni. There are also minorities who are Shia (7%), Ahmadiyya (4%) and those that are non-denominational Muslims, Sufi Muslims or Muwahhid Muslims.[115][116] The remainder of the population follow traditional religions (1%), Baha'i (0.1%), other non-Christian religions (0.7%), or have no religious affiliation (0.9%).[114] The Muslims in Uganda are allowed to practice polygamy, and divorce is very rare.

The northern and West Nile regions are predominantly Catholic, while the Iganga District in eastern Uganda has the highest percentage of Muslims. The rest of the country has a mix of religious affiliations.[117]

Prior to the advent of religions such as Christianity and Islam, traditional indigenous beliefs were practised as a means of ensuring welfare of the people were maintained at all times. Even today in contemporary times, these practices are rife in some rural areas and are sometimes blended with or practised alongside Christianity or Islam. In addition to a small community of Jewish expatriates centred in Kampala, Uganda is home to the Abayudaya, a native Jewish community dating from the early 1900s. One of the world's seven Bahá'í Houses of Worship is located on the outskirts of Kampala. See also Bahá'í Faith in Uganda.

Indian nationals are the most significant immigrant population; members of this community are primarily Ismaili (Shi'a Muslim followers of the Aga Khan) or Hindu.

Largest cities

| | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | District | Pop. | ||||||

Kampala Gulu |

1 | Kampala | Kampala | 1,353,189 | |||||

| 2 | Gulu | Gulu | 146,858 | ||||||

| 3 | Lira, Uganda | Lira | 119,323 | ||||||

| 4 | Mbarara | Mbarara | 97,500 | ||||||

| 5 | Jinja | Jinja | 93,061 | ||||||

| 6 | Bwizibwera | Mbarara | 79,157 | ||||||

| 7 | Mbale | Mbale | 76,493 | ||||||

| 8 | Mukono | Mukono | 67,290 | ||||||

| 9 | Kasese | Kasese | 67,269 | ||||||

| 10 | Masaka | Masaka | 65,373 | ||||||

Culture

Owing to the large number of communities, culture within Uganda is diverse. Many Asians (mostly from India) who were expelled during the regime of Amin have returned to Uganda.[118]

Music

Ugandan music is as diverse as the ethnicity of its people. The country is home to over 30 different ethnic groups and tribes and they form the basis of all indigenous music. The Baganda, being the most prominent tribe in the country, have dominated the culture and music of Uganda over the last two centuries. However, the other tribes all have their own music styles passed down from generations dating back to the 18th century if not earlier. These variations all make for good diversity in music and culture.

Music is an important cultural and communicative tool in Uganda. In recent years, Smithsonian Folkways has produced two albums featuring traditional music of the region: "Abayudaya: Music from the Jewish People of Ugandan" and "Delicious Peace: Coffee, Music & Interfaith Harmony in Uganda"

Besides traditional music, modern musicians have also emerged. These Musicians have featured both on local and international charts. Some of the popular Ugandan musicians include

- Late Philly Bongore Lutaaya

- Late Elly Wamala

- Late Paul Kafeero

- Juliana Kanyomozi

- Bobi Wine

- Bebe Cool

- Chameleone

- Pallaso

- Radio and Weasel, the Goodlyfe Crew

- Jamal Wasswa

- Viboyo

- Eddy Kenzo

- Desire Luzinda

- Lady Mariam Tindatine

Sport

Football

Football is the national sport in Uganda. Games involving the Ugandan national football team usually attract large crowds of Ugandans from all walks of life. The Ugandan Super League is the top division of Ugandan football contested by 16 clubs from across the country; it was created in 1968. Football in Uganda is managed by the Federation of Uganda Football Associations (FUFA). The association administers the national football team, as well as the Super League.

South African broadcaster DStv through its Super Sport network broadcasts the Ugandan League to 46 different countries in sub Saharan Africa. Football is played all over Uganda especially by children in schools and young people on a variety of pitch surfaces. Uganda's most famous footballers are David Obua of Scottish club Hearts and Ibrahim Sekagya, who was the captain of the national team, Austria's Red Bull Salzburg and Nestroy Kizito. Uganda's notable past greats of the game include Denis Obua, Majid Musisi, Fimbo Mukasa and Paul Kasule.

.jpg)

Cricket

Cricket has experienced rapid growth in Uganda, although football is the national sport. Recently in the Quadrangular Tournament in Kenya, Uganda came in as the underdogs and went on to register a historic win against archrivals Kenya. Uganda also won the World Cricket League (WCL) Division 3 and came in fourth place in the WCL Division 2. In February 2009, Uganda finished as runner-up in the WCL Division 3 competition held in Argentina, thus gaining a place in the World Cup Qualifier held in South Africa in April 2009.

Rugby

In 2007, the Uganda national rugby union team were victorious in the 2007 Africa Cup, beating Madagascar in the final.

Motorsport

Rallying is a popular sport in Uganda with the country having successfully staged a round of the African Rally Championship (ARC), Pearl of Africa Rally since 1996, when it was a candidate event. The country has gone on to produce African rally champions such as Charles Muhangi, who won the 1999 ARC crown. Other notable Ugandans on the African rally scene include Riyaz Kurji, who was killed in a fatal accident while leading the 2009 edition, Emma Katto, Karim Hirji, Chipper Adams and Charles Lubega. Ugandans have also featured prominently in the Safari Rally.

Hockey

Ugandans have played hockey since the early 1920s. It was originally played by Asians, but now is widely played by people from other racial backgrounds. Hockey is the only Ugandan field sport to date to have qualified for and represented the country at the Olympics; this was at the 1972 Summer Olympics. Uganda has won gold medals at the Olympics in athletics with legendary hurdler John Akii-Bua in 1972 and marathon winner at the London 2012 Olympics Stephen Kiprotich.

Baseball

In July 2011 Kampala, Uganda qualified for the 2011 Little League World Series in Williamsport, Pennsylvania for the first time, beating Dharan LL in Saudi Arabia, though due to visa complications they were unable to attend the Series.[119] In 2012, Uganda qualified again for the Little League World Series; and, the team was able to finally make its first appearance at the tournament in Williamsport.

Lacrosse

Uganda competed in the 2014 FIL World Lacrosse Championships in Denver. Uganda finished 34th with victories over Korea and Argentina.

Cuisine

Ugandan cuisine consists of traditional cooking with English, Arab, and Asian (especially Indian) influences. Like the cuisines of most countries, it varies in complexity, from the most basic, a starchy filler with a sauce of beans or meat, to several-course meals served in upper-class homes and high-end restaurants.

Main dishes are usually centred on a sauce or stew of groundnuts, beans or meat. The starch traditionally comes from ugali (maize meal) in the North, South and East, matoke (boiled and mashed green banana) in Central Uganda, or an ugali made from millet in the West and Northwest. Cassava, yam, and African sweet potato, Sweet potatoes are also eaten; the more affluent include white (often called "Irish") potato and rice in their diets. Soybeans were promoted as a healthy food staple in the 1970s and are also used occasionally for breakfast. Chapati, an Asian flatbread, is also part of Ugandan cuisine.

Cinema

The Ugandan film industry is relatively young. It is developing quickly, but still faces an assortment of challenges. Recently there has been support for the industry as seen in the proliferation of film festivals such as Amakula, Pearl International Film Festival, Maisha African Film Festival and Manya Human Rights Festival. However filmmakers struggle against the competing markets from other countries on the continent such as those in Nigeria and South Africa in addition to the big budget films from Hollywood.[120]

The first publicly recognised film that was produced solely by Ugandans was Feelings Struggle, which was directed and written by Hajji Ashraf Ssemwogerere in 2005.[121] This marks the year of assent of film in Uganda, a time where many enthusiasts were proud to classify themselves as cinematographers in varied capacities.[122]

The local film industry is currently polarised between two types of filmmakers. The first are filmmakers who use the guerrilla Nollywood (cinema of Nigeria) approach to filmmaking, churning out a picture in around two weeks and screening it in makeshift video halls. The second is the filmmaker who has the film aesthetic, but with limited funds has to depend on the competitive scramble for donor cash.[120]

Though cinema in Uganda is evolving it still faces major challenges. Along with technical problems such as refining acting and editing skills, there are issues regarding funding and lack of government support and investment. There are no schools in the country dedicated to film, banks do not extend credit to film ventures, and distribution and marketing of movies remains poor.[120][122]

The Uganda Communications Commission (UCC) is currently preparing regulations starting in 2014 that require Ugandan television to broadcast 70 percent Ugandan content and of this, 40 percent to be independent productions. With the emphasis on Ugandan Film and the UCC regulations favouring Ugandan productions for mainstream television, Ugandan film may become more prominent and successful in the near future.[122]

Tourism

See also

References

- ↑ http://www.ubos.org/onlinefiles/uploads/ubos/pdf%20documents/2002%20Census%20Final%20Reportdoc.pdf

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Central Intelligence Agency (2009). "Uganda". The World Factbook. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Uganda". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ↑ "Gini Index". World Bank. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ↑ "2014 Human Development Report Summary" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2014. pp. 21–25. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ↑ "East Africa Living Encyclopedia – Ethnic Groups". African Studies Center, University of Pennsylvania.

- ↑ Martin, Phyllis and O'Meara, Patrick (1995). Africa. 3rd edition. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253209846.

- ↑ Mwambutsya, Ndebesa (June 1990 and January 1991). "Pre-capitalist Social Formation: The Case of the Banyankole of Southwestern Uganda". Eastern Africa Social Science Research Review 6 (2; 7 no. 1): 78–95. Archived from the original on 31 January 2008. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Origins of Bunyoro-Kitara Kings" at the Wayback Machine (archived 10 December 2006), bunyoro-kitara.com.

- ↑ Stanley, H.M., 1899, Through the Dark Continent, London: G. Newnes, ISBN 0486256677

- ↑ "Background Note: Uganda", U.S. State Department

- ↑ https://www.ral.ucar.edu/projects/plague-in-uganda

- ↑ "Reanalyzing the 1900–1920 Sleeping Sickness Epidemic in Uganda". USA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- ↑ History of Parliament at the Wayback Machine (archived 20 February 2010) (Website of the Parliament of Uganda)

- ↑ "Buganda Kingdom: The Uganda Crisis, 1966". Buganda.com. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ "Department of State. Background Note: Uganda". State.gov. 3 February 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ "A Country Study: Uganda", Library of Congress Country Studies

- ↑ Keatley, Patrick (18 August 2003). "Obituary: Idi Amin". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- ↑ "UK Indians taking care of business", The Age (8 March 2006). Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ Henry Wasswa, “Uganda's first prime minister, and two-time president, dead at 80,” Associated Press, 10 October 2005

- ↑ "'New-Breed' Leadership, Conflict, and Reconstruction in the Great Lakes Region of Africa: A Sociopolitical Biography of Uganda's Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, Joseph Oloka-Onyango," Africa Today – Volume 50, Number 3, Spring 2004, p. 29

- ↑ "No End to LRA Killings and Abductions". Human Rights Watch. 23 May 2011.

- ↑ "World Heritage List". Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ↑ "Parliament of Uganda Website :: – COMPOSITION OF PARLIAMENT". Parliament.go.ug. Archived from the original on 20 February 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ↑ Article 19. (2013). Uganda: Public Order Management Bill.

- ↑ Masereka, Alex. (2013). M7 Okays Public Order Bill. Red Pepper.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 United States Department of State (Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor).(2012). Uganda 2012 Human Rights Report.

- ↑ Natabaalo, Grace. (2013). Ugandan Police Shutdown Papers Over 'Plot'. Al Jazeera.

- ↑ "Uganda 2011 Elections" (PDF). European Union Election Observation Mission. 20 February 2011.

- ↑ Roberts, Scott (13 November 2012) Hacktivists target Ugandan lawmakers over anti-gay bill. pinknews.co.uk

- ↑ Roberts, Scott (14 November 2012) Pressure on Uganda builds over anti-gay law. pinknews.co.uk

- ↑ "2012 Corruption Perceptions Index". Transparency International. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ Transparency International. (2012). Corruption Perceptions Index 2012.

- ↑ "Piglets released in Ugandan parliament investigated for terrorism". Uganda News.Net. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ↑ Human Rights Watch. (2013). Letting the Big Fish Swim.

- ↑ "A Snapshot of Corruption in Uganda". Business Anti-Corruption Portal. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ↑ Biryabarema, Elias. (2012). Ugandan Lawmakers Pass Oil Bill, Worry About Corruption. Thomson Reuters

- ↑ Global Witness. (2012). Uganda's oil laws: Global Witness Analysis.

- ↑ The International Center for Not-For-Profit Law. (2012). NGO Law Monitor: Uganda.

- ↑ "Can Uganda's economy support more districts?", New Vision, 8 August 2005

- ↑ Uganda Local Government Association. Ulga.org. Retrieved on 19 July 2013.

- ↑ Tumushabe, Alfred (22 September 2012) Ankole monarchists' two decade battle for restoration of kingdom. monitor.co.ug.

- ↑ "UGANDA: A rough guide to the country's kingdoms"

- ↑ http://www.monitor.co.ug/OpEd/OpEdColumnists/CharlesOnyangoObbo/With-Somalia--CAR--and-South-Sudan--Museveni/-/878504/2137720/-/eb4y1nz/-/index.html

- ↑ "AFP: Attacks of 'appalling brutality' in DR Congo: UN". Google. 10 February 2009. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ↑ "Uganda: Respect Opposition Right to Campaign", Human Rights Watch, 19 December 2005

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 47.4 Refworld | 2010 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor – Uganda. UNHCR (3 October 2011). Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ "World Refugee Survey 2008". U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants. 19 June 2008. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009.

- ↑ Human Rights Watch. (2013). World Report 2013 (Uganda).

- ↑ "Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people" at the Wayback Machine (archived 11 March 2008), Amnesty International Report 2007 Uganda

- ↑ "Ugandan paper calls for gay people to be hanged", Xan Rice, The Guardian, 21 October 2010

- ↑ "Ugandan gay rights activist: 'I have to watch my back more than ever'", 5 November 2010

- ↑ "Uganda: Stop homophobic campaign launched by Rolling Stone tabloid", 14 October 2010, No Peace Without Justice

- ↑ "Uganda Newspaper Published Names/Photos of LGBT Activists and HRDs – Cover Says 'Hang Them'", International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association

- ↑ Akam, Simon (22 October 2010) "Outcry as Ugandan paper names 'top homosexuals'", The Independent

- ↑ "Uganda gay rights activist David Kato killed", 27 January 2011, BBC News

- ↑ Sharlet, Jeff (September 2010). "Straight Man's Burden: The American roots of Uganda's anti-gay persecutions". Harper's (Harper's Magazine Foundation) 321 (1,924): 36–48. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- ↑ Brocklebank, Christopher (15 August 2012). Anonymous hack into Ugandan government websites in protest at their anti-LGBT policies. Pinknews.co.uk

- ↑ "Uganda's anti-gay law prompts World Bank to postpone $90mn loan", 28 February 2014|publisher=Uganda News.Net

- ↑ Quarterly Macroeconomic Report Q4 2010. Bank of Uganda, March 2011

- ↑ http://tourism.go.ug/index.php?option=com_phocadownload&view=category&download=10:ubos-statistical-abstract&id=4:statistics&Itemid=300

- ↑ "Snapshot of Uganda's economic outlook". African Economic Outlook. 6 July 2009.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Uganda's oil rush: Derricks in the darkness. Economist.com (6 August 2009). Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ "Uganda at a Glance" (PDF). World Bank. 13 November 2009.

- ↑ Interview of David Hines in 1999 by W. D. Ogilvie; obituary of David Hines in London Daily Telegraph 8 April 2000 written by W. D. Ogilvie

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 "Economic growth and the MDGs – Resources – Overseas Development Institute". ODI. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ↑ "List of Licensed Investment Banks & Stock Brokerage Firms in Uganda". Use.or.ug. 31 December 2001. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ↑ Kaujju, Peter (June 2008). "Capital markets eye pension reform". The New Vision. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ↑ Rutaagi, Edgar (2009). "Uganda Moving Towards Pension Reforms". The African Executive. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ↑ Mbunga, Paskal. "Tanzania And Uganda Agree To Speed Up Railway Project". Businessdailyafrica.com8 November 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ↑ "Migration and Remittances Factbook 2011" (PDF). World Bank.

- ↑ Ondoga, Ayiga (June 2008). "Arua: West Nile's business hub". The New Vision.

- ↑ Yoshino, Yutaka; Ngungi, Grace and Asebe, Ephrem. ": Enhancing the Recent Growth of Cross-Border Trade between South Sudan and Uganda Africa Trade Policy Notes

- ↑ Muwanga, David (March 2010) "Uganda, Rwanda Border to Run 24hrs". AllAfrica.com

- ↑ "Poverty headcount ratio at $1.25 a day (PPP) (% of population)". World Bank. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ↑ "Enabling Poor People to Overcome Poverty in Uganda" (PDF). International Fund for Agricultural Development. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ↑ "IFAD Gender Strengthening Programme" (PDF). International Fund for Agricultural Development. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ↑ "From Periphery to Center: A Strategic Country Gender Assessment" (PDF). World Bank. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ↑ "AVERTing HIV and AIDS". AVERT. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ↑ Ekirapa-Kiracho, E (2011). "Increasing Access To Institutional Deliveries Using Demand And Supply Side Incentives: Early Results From A Quasi-Experimental Study". BMC International Health and Human Rights 11 (Suppl 1): S11. doi:10.1186/1472-698x-11-s1-s11. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ↑ Peters, David et al. (2011). "Exploring New Health Markets: Experiences From Informal Providers Of Transport For Maternal Health Services In Eastern Uganda". BMC International Health and Human Rights 11 (Suppl 1): S10. doi:10.1186/1472-698x-11-s1-s10. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ↑ "Gender Equity Issues in Uganda". Foundation for Sustainable Development. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ↑ http://www.budde.com.au/Research/Uganda-Mobile-Market-Overview-Statistics-and-Forecasts.html

- ↑ Ogwang, Joel. (21 December 2012) Uganda: Communications Sector Registers Mixed Fortunes in 2012 (Page 2 of 3). allAfrica.com. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ Heritage Oil | Timeline. Heritageoilplc.com. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 86.2 "Human Development Report 2009 – Uganda [Archived]". Hdrstats.undp.org. Archived from the original on 29 April 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ Kelly, Annie (1 December 2008) "Background: HIV/Aids in Uganda". The Guardian.

- ↑ "UNAIDS: Uganda Profile". UNAIDS. Retrieved 22 @ERROR@ 2012. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ Kamali, A.; Carpenter, L. M.; Whitworth, J. A.; Pool, R.; Ruberantwari, A.; Ojwiya, A. (2000). "Seven-year trends in HIV-1 infection rates, and changes in sexual behaviour, among adults in rural Uganda". AIDS (London, England) 14 (4): 427–434. doi:10.1097/00002030-200003100-00017. PMID 10770546.

- ↑ UNICEF 2013, p. 27.

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/8406940.stm

- ↑ CIA World Factbook: Life Expectancy ranks

- ↑ CIA World Factbook: Infant Mortality ranks

- ↑ "Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2006" (PDF). Measure DHS. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ "Improving Access to Safe Deliveries in Uganda". Future Health Systems. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ "Women's Perceptions of ANC and delivery care Services, a community perspective" (PDF). Future Health Systems. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ↑ The MDGs and equity. Overseas Development Institute, June 2010

- ↑ Dugger, Celia (29 July 2011). "Maternal Deaths Focus Harsh Light on Uganda". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ Rutebemberwa, E.; Ekirapa-Kiracho, E.; Okui, O.; Walker, D.; Mutebi, A.; Pariyo, G. (2009). "Lack of effective communication between communities and hospitals in Uganda: A qualitative exploration of missing links". BMC Health Services Research 9: 146. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-9-146. PMC 2731748. PMID 19671198.

- ↑ Kiguli, Julie et al. (2009). "Increasing access to quality health care for the poor: community perceptions on quality care in Uganda". Patient Preference and Adherence 3. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 Pariyo, G et al. (2009). "Changes in Utilization of Health Services among Poor and Rural Residents in Uganda: Are Reforms Benefitting the Poor?". Int J for Equity in Health. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ↑ "Ebola Outbreak Spreads". Daily Express. Associated Press. 31 July 2012.

- ↑ Biryabarema, Elias (5 October 2012). "Uganda says it is now free of deadly Ebola virus". Reuters.

- ↑ "Three die in Uganda from Ebola-like fever: Health Ministry". Yahoo News. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ↑ ADF recruiting in Mayuge, Iganga says army. Newvision.co.ug (3 January 2013). Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ Zinkina J., Korotayev A. Explosive Population Growth in Tropical Africa: Crucial Omission in Development Forecasts (Emerging Risks and Way Out). World Futures 70/2 (2014): 120–139.

- ↑ Uganda Bureau Of Statistics (UBOS) (November 2015). National Population and Housing Census 2014. Provisional Results (PDF) (Revised ed.). Kampala, Uganda. p. 6. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ↑ Uganda: Return of the exiles at the Wayback Machine (archived 11 June 2010). The Independent, 26 August 2005

- ↑ "Their Suffering, Our Burden? How Congolese Refugees Affect the Ugandan Population" (PDF). World Bank. 9 June 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ↑ "The Constitution (Amendment) Act 2005" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 September 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ "Museveni Signs 3rd Term Bill". New Vision (Kampala). 29 September 2005.

From now on, Swahili is the second official language...

- ↑ Swahili in the UCLA Language Materials Project

- ↑ "A Brief History of the Swahili Language", glcom.com

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 114.2 "2002 Uganda Population and Housing Census – Main Report" (PDF). Uganda Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 26 March 2008.

- ↑ "The World's Muslims: Unity and Diversity" (PDF). Pew Forum on Religious & Public life. 9 August 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ↑ oded, Arye (2000). Islam and Politics in Kenya. p. 163.

- ↑ "U.S. Department of State". State.gov. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ↑ Lorch, Donatella (22 March 1993). "Kampala Journal; Cast Out Once, Asians Return: Uganda Is Home". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ Adeyemi, Bandele (19 August 2011). "Frustrating View of Game Day". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 120.2 Telling the story against all odds; state of Uganda film industry. Cannes vu par. Retrieved on 19 July 2013.

- ↑ Rasmussen, Kristin Alexandra (2010) Kinna-Uganda: A review of Uganda's national cinema. Master's Theses. Paper 3892. The Faculty of the Department of TV, Radio, Film, Theatre Arts, San José State University, US

- ↑ 122.0 122.1 122.2 Ugandan film’s leap – Theatre & Cinema. monitor.co.ug. Retrieved on 19 July 2013.

Further reading

- Encyclopedias

- Appiah, Anthony and Henry Louis Gates (ed). Encyclopaedia of Africa (2010). Oxford University Press.

- Middleton, John (ed). New encyclopaedia of Africa (2008). Detroit: Thompson-Gale.

- Shillington, Kevin (ed). Encyclopedia of African history (2005). CRC Press.

- Selected books

- BakamaNume, Bakama B. A Contemporary Geography of Uganda. (2011) African Books Collective.

- Robert Barlas (2000). Uganda (Cultures of the World). Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 9780761409816. OCLC 41299243. overview written for younger readers.

- Chrétien, Jean-Pierre. The great lakes of Africa: two thousand years of history (2003). New York: Zone Books.

- Hodd, Michael and Angela Roche. Uganda handbook (2011) Bath: Footprint.

- Jagielski, Wojciech and Antonia Lloyd-Jones. The night wanderers: Uganda's children and the Lord's Resistance Army. (2012). New York: Seven Stories Press. ISBN 9781609803506

- Otiso, Kefa M. Culture And Customs of Uganda. (2006) Greenwood Publishing Group.

External links

- Overview

- Uganda entry at The World Factbook

- Uganda from UCB Libraries GovPubs.

- Country Profile from BBC News.

- Uganda Corruption Profile from the Business Anti-Corruption Portal

- Welcome To Uganda - The Uganda Guide and Information Portal

- Uganda at DMOZ

- Maps

- Government and economy

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

- Key Development Forecasts for Uganda from International Futures.

- .

- Humanitarian issues

- Humanitarian news and analysis from IRIN – Uganda

- Humanitarian information coverage on ReliefWeb

- Radio France International – dossier on Uganda and Lord's Resistance Army

- Trade

- Tourism

- Uganda Tourist Board

-

Uganda travel guide from Wikivoyage

Uganda travel guide from Wikivoyage

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)

.svg.png)