U.S. postal strike of 1970

| U.S. postal strike of 1970 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Striking postal workers highlight the disparity in wages between themselves and the politicians | ||||

| Date | March 18–25, 1970 (approximately) | |||

| Location | began in New York City, spread across the United States | |||

| Causes | Low wages and/or poor working conditions | |||

| Result | Postal Reorganization Act | |||

| Parties to the civil conflict | ||||

| ||||

| Lead figures | ||||

| ||||

| Number | ||||

| ||||

The U.S. postal strike of 1970 was a two-week strike by federal postal workers in March 1970. The strike began in NYC and spread to some other cities in the following two weeks. The strike was illegal, against the federal government, and the largest wildcat strike in U.S. history.[1]

President Richard Nixon called out the United States armed forces and the National Guard in an attempt to distribute the mail and break the strike.

The strike influenced the contents of the Postal Reorganization Act of 1970, which transformed the Post Office into the more corporate United States Postal Service and guaranteed collective bargaining rights (though not the right to strike.)

Causes

At the time, postal workers were not permitted by law to engage in collective bargaining. Striking postal workers felt wages were very low, benefits poor and working conditions unhealthy and unsafe. APWU president Moe Biller described Manhattan (New York City) post offices as like "dungeons," dirty, stifling, too hot in summer, and too cold in winter.[1]

The U.S. Post Office Department's management was outdated and, according to workers, haphazard. Postal union lobbying of Congress to obtain higher pay and better working conditions had proven fruitless.[1]

An immediate trigger for the strike was a Congressional decision to raise the wages of postal workers by only 4%, at the same time as Congress raised its own pay by 41%.[2][3][4]

The Post Office was home to many black workers, and this population increased as whites left postal work in the 50s and 60s for better jobs. Postal workers in general were upset about the low wages and poor conditions.[1][5] [1]

The importance of black workers was amplified by militancy outside the post office.[1] Isaac & Christiansen identify the civil rights movement as a major contributor to the 1970 strike as well as other radical labor actions. They highlight several causal connections, including cultural climate, overlapping personnel, and the simple "demonstration effect," showing that nonviolent civil disobedience could accomplish political change.[6]

The strike

On March 17, 1970, in New York City, members of National Association of Letter Carriers (NALC) Branch 36 met in Manhattan and voted to strike. Picketing began just after midnight, on March 18. This was a mass action where rank and file leaders emerged like Manhattan letter carrier Vincent Sombrotto, who would go on to be elected first branch and then national president of the NALC.[1]

More than 210,000 United States Post Office Department workers were eventually involved across the nation, although initially the strike affected only workers in New York City. These workers decided to strike against the wishes of their leadership. The spontaneous unity produced by this decision empowered the workers.[7]

President Nixon appeared on national television and ordered the employees back to work, but his address only stiffened the resolve of the existing strikers and angered workers in another 671 locations in other cities into walking out as well. Workers in other government agencies also announced they would strike if Nixon pursued legal action against the postal employees.[7]

Authorities were unsure of how to proceed. Union leaders pleaded with the workers to return to their jobs. The government was hesitant to arrest strike leaders for fear of arousing sympathy among other workers, and because of popular support for the strikers.[8]

Impact

The strike crippled the nation's mail system.[1]

The stock market fell due to the strike's effect on trading volume.[9] Some feared that the stock market would have to close entirely.[8]

Nixon summons the National Guard

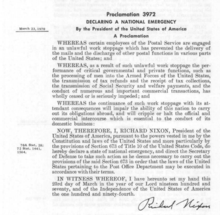

Nixon spoke to the nation again on March 23, asking the workers to go back to their jobs and announcing that he would deploy the National Guard to deliver mail in New York.[10] This announcement was accompanied by Proclamation 3972, which declared a national emergency.[11]

Nixon then ordered 24,000 military personnel forces to begin distributing the mail. Operation Graphic Hand had at its peak more than 18 500 military personnel assigned to 17 New York post offices, from regular Army, National Guard, Army Reserve, Air National Guard and Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps Reserve.[12]

The national emergency was never revoked. The resulting expansion of presidential power was investigated in 1973 by a Congressional body called the Special Committee on the Termination of the National Emergency, which cautioned that the national emergency status gave the president the right to seize property, organize the means of production, and institute martial law.[13]

Conclusion

The strike ended after eight days with not a single worker being fired, as the Nixon administration continued to negotiate with postal union leaders.[1]

Outcomes

Postal Reorganization Act

The postal strike influenced the passage and signing of the Postal Reorganization Act of 1970. Effective July 1, 1971, the U.S. Post Office Department became the U.S. Postal Service, an independent establishment of the executive branch. The four major postal unions (National Association of Letter Carriers, American Postal Workers Union, National Postal Mail Handlers Union, and the National Rural Letter Carriers Association) won full collective bargaining rights: the right to negotiate on wages, benefits and working conditions, although they still were not allowed the right to strike.[1]

American Postal Workers Union

On July 1, 1971, five federal postal unions merged to form the American Postal Workers Union, the largest postal workers union in the world.[3]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Rubio, Philip F. (2010). There's Always Work at the Post Office: African-American postal workers and the fight for jobs, justice, and equality. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 446. ISBN 9780807859865.

- ↑ NPMBlog@si.edu (17 March 2010). "The 1970 Postal Strike". Pushing the Envelope Blog. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "APWU History". American Postal Workers Union, AFL-CIO. Retrieved 2009-08-28.

- ↑ "The Strike that Stunned the Country". Time Magazine. 30 March 1970. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ Carter, Art (31 March 1970). "NAPE pickets PO talks". Washington Afro-American. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ Isaac, Larry; Lars Christiansen (October 2002). . "How the Civil Rights Movement Revitalized Labor Militancy". American Sociological Review, 67 (5): 722–746. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Notes on the Postal Strike, 1970". Root & Branch. pp. 1–5. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Times Wire Service (20 March 1970). "Wildcat Postal Strike Worsens; 3 States Hit". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ "Stocks Sag on Low Volume Due to Postal Strike". Palm Beach Post. 20 March 1970. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ Nixon, Richard (24 March 1970). "Text of Nixon Speech on Post Office Crisis". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ Nixon, Richard. "PROCLAMATION 3972". Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ Bell, William Gardner, ed. (1973). "Operational Forces". Department of the Army Historical Summary: Fiscal Year 1970. Washington, D.C.: Center of military history United States army. p. 15. Retrieved 2009-08-28.

- ↑ Higgs, Robert; Twight, Charlotte (1 January 1987). "National Emergency and the Erosion of Private Property Rights". The Independent Institute. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

External links

- Video of President Nixon announcing federal intervention in the postal strike

- "Chapter 7: Nixon and Ford Administrations, 1969-1977" Brief History of DOL, U.S. Dept. of Labor. Accessed December 5, 2006.

- Video footage of strikers & Nixon