Typhoon Cobra (1944)

| Category 4 (Saffir–Simpson scale) | |

Eye structure captured on radar | |

| Formed | December 14, 1944 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | December 19, 1944[1] |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 230 km/h (145 mph) Gusts: 220 km/h (140 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | ≤ 907 mbar (hPa); 26.78 inHg |

| Fatalities | 790 U.S., unknown elsewhere |

| Areas affected | Philippine Sea |

| Part of the 1944 Pacific typhoon season | |

Typhoon Cobra, also known as the Typhoon of 1944 or Halsey's Typhoon (named after Admiral William 'Bull' Halsey), was the United States Navy designation for a tropical cyclone which struck the United States Pacific Fleet in December 1944 during World War II.

Task Force 38 (TF 38) had been operating about 300 mi (260 nmi; 480 km) east of Luzon in the Philippine Sea conducting air raids against Japanese airfields in the Philippines. The fleet was attempting to refuel its ships, especially the lighter destroyers, which had limited fuel carrying capacity. As the weather worsened it became increasingly difficult to refuel, and the attempts had to be discontinued. Despite warning signs of worsening conditions, the ships of the fleet remained in their stations. Worse, the information given to Halsey about the location and direction of the typhoon was inaccurate. On December 17, Admiral Halsey unwittingly sailed Third Fleet into the heart of the typhoon.

Because of 100 mph (87 kn; 160 km/h) winds, very high seas and torrential rain, three destroyers capsized and sank, and a total of 790 lives were lost. Nine other warships were damaged, and over 100 aircraft were wrecked or washed overboard; the aircraft carrier Monterey was forced to battle a serious fire that was caused by a plane hitting a bulkhead.

USS Tabberer—a small John C. Butler-class destroyer escort—lost her mast and radio antennas. Though damaged and unable to radio for help, she took the initiative to remain on the scene to recover 55 of the 93 total that were rescued. Captain Henry Lee Plage earned the Legion of Merit, while the entire crew earned the Navy's Unit Commendation Ribbon, which was presented to them by Admiral Halsey.

In the words of Admiral Chester Nimitz, the typhoon's impact "represented a more crippling blow to the Third Fleet than it might be expected to suffer in anything less than a major action". The events surrounding Typhoon Cobra were similar to those the Japanese navy itself faced some nine years earlier in what they termed the "Fourth Fleet Incident."

This typhoon also led to the establishment of weather infrastructure of the US Navy, which eventually became the Joint Typhoon Warning Center.

A typhoon plays an important role in the novel The Caine Mutiny, which is thought to be based on the author's own experience surviving Typhoon Cobra.

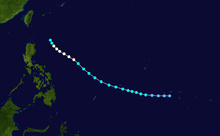

Meteorological history

On December 17, the typhoon was first observed, surprising a fleet of ships in the open western Pacific Ocean. Barometric pressures as low as 26.8 inHg (907 mbar) and wind speeds up to 120 kn (140 mph; 220 km/h) in gusts were reported by some ships. The storm was last seen on the 18th.

Task Force 38

TF 38 consisted of seven fleet carriers, six light carriers, eight battleships, 15 cruisers, and about 50 destroyers. The carriers had been conducting raids against Japanese airfields in the Philippines and ships were being refueled, especially many destroyers running low on fuel. When the storm hit, the procedure had to be aborted.

Some ships experienced rolls of over 70° and damage suffered by the fleet was severe. Three destroyers, Spence, Hickox, and Maddox, had nearly empty fuel stores (10-15% of capacity) and therefore lacked the stabilizing effect of the extra weight and thus were relatively unstable. Additionally, several other destroyers, including Hull and Monaghan, were of the older Farragut-class and had been refitted with over 500 long tons (510 t) of extra equipment and armament which made them top-heavy.

Spence, Hull, and Monaghan were sunk either by capsizing outright, or as a result of water down-flooding through their smokestacks and disabling their engines. Without power, they were unable to control their heading and were at the mercy of the wind and seas. Hickox and Maddox, due to ballasting of their empty fuel tanks (pumping them full of seawater), had greater stability and were able to ride out the storm with relatively minor damage.

Many other ships of TF 38 suffered various degrees of damage, especially to radar and radio equipment which severely compromised communications within the fleet. Several carriers suffered fires on their hangars and 146 aircraft were wrecked or blown overboard. Nine ships— including one light cruiser, three light carriers, and two escort carriers—suffered severe damage and had to be sent for repairs.

The carrier Monterey was nearly taken down in flames by its own airplanes as they crashed into bulkheads and exploded during violent rolls. One of those fighting the fires aboard Monterey was then-Lt. Gerald Ford, later President of the United States. Ford later recalled nearly going overboard; when 20° and greater rolling caused aircraft below decks to careen into each other, igniting a fire. Ford, serving as General Quarters Officer of the Deck, was ordered to go below to assess the raging fire. He did so safely, and reported his findings back to the ship’s commanding officer, Captain Stuart Ingersoll. The ship’s crew was able to contain the fire, and the ship got underway again.[2]

_during_Typhoon_Cobra.jpg)

18 December 1944.

_and_battleship_in_typhoon_1944.jpeg)

3rd Fleet damages

- USS Hull - with 70% fuel aboard, capsized and sunk with 202 men drowned (62 survivors)[3]

- USS Monaghan - capsized and sunk with 256 men drowned (six survivors)[3]

- USS Spence - rudder jammed hard to starboard, capsized and sunk with 317 men drowned (23 survivors) after hoses parted attempting to refuel from New Jersey because they had also disobeyed orders to ballast down directly from Admiral Halsey[3]

- USS Cowpens - hangar door torn open and RADAR, 20mm gun sponson, whaleboat, jeeps, tractors, kerry crane, and 8 aircraft lost overboard. One sailor lost.[3]

- USS Monterey - hangar deck fire killed three men and caused evacuation of boiler rooms requiring repairs at Bremerton Navy yard[3]

- USS Langley - damaged[3]

- USS Cabot - damaged[4]

- USS San Jacinto - hangar deck planes broke loose and destroyed air intakes, vent ducts and sprinkling system causing widespread flooding.[3] Damage repaired by USS Hector[5]

- USS Altamaha - hangar deck crane and aircraft broke loose and broke fire mains[3]

- USS Anzio - required major repair[3]

- USS Nehenta - damaged[4]

- USS Cape Esperance - flight deck fire required major repair[3]

- USS Kwajalein - lost steering control[3]

- USS Iowa - propeller shaft bent and lost a seaplane

- USS Baltimore - required major repair[3]

- USS Miami - required major repair[3]

- USS Dewey - lost steering control, RADAR, the forward stack, and all power when salt water shorted main electrical switchboard[3]

- USS Aylwin - required major repair[3]

- USS Buchanan - required major repair[3]

- USS Dyson - required major repair[3]

- USS Hickox - required major repair[3]

- USS Maddox - damaged[4]

- USS Benham - required major repair[3]

- USS Donaldson - required major repair[3]

- USS Melvin R, Nawman - required major repair[3]

- USS Tabberer - lost foremast[6]

- USS Waterman - damaged[4]

- USS Nantahala - damaged[4]

- USS Jicarilla - damaged[4]

- USS Shasta - damaged "one deck collapsed, aircraft engines damaged, depth charges broke loose, damaged "

Rescue efforts

The fleet was scattered by the storm. One ship, the destroyer escort Tabberer, encountered and rescued a survivor from Hull while itself desperately fighting the typhoon. This was the first survivor from any of the capsized destroyers to be picked up. Shortly thereafter, many more survivors were picked up, in groups or in isolation. Tabberer 's skipper—Lieutenant Commander Henry Lee Plage—directed that the ship, despite its own dire condition, begin boxed searches to look for more survivors.

Tabberer eventually rescued 55 survivors in a 51-hour search, despite repeated orders from Admiral Halsey to return all ships to port in Ulithi. She picked up 41 men from Hull and 14 from Spence before finally returning to Ulithi after being directly relieved from the search by two destroyer escorts.

After the fleet had regrouped (without Tabberer), ships and aircraft conducted search and rescue missions. The destroyer Brown rescued the only survivors from Monaghan, six in total. She additionally rescued 13 sailors from Hull. Eighteen other survivors from Hull and Spence were rescued over the three days following Typhoon Cobra by other ships of the 3rd Fleet. The destroyer USS The Sullivans (DD-537) emerged from the storm undamaged and began looking for survivors before returning to Ulithi on Christmas Eve.[7] In all, 93 men were rescued of the over 800 men presumed missing in the three ships, and two others who had been swept overboard from the escort carrier Anzio.

Despite disobeying fleet orders, Plage was awarded the Legion of Merit by Admiral Halsey, and Tabberer's crew each were awarded Navy Unit Commendation ribbons (the first ever awarded).

Investigation

While conducting operations off the Philippines, the Third Fleet remained on station rather than breaking up and running from the storm. This led to a loss of men, ships and aircraft. A Navy court of inquiry was convened on board the USS Cascade at the Naval base at Ulithi. Admiral Nimitz, CINCPAC, was in attendance at the court. Forty-three-year-old Captain Herbert K. Gates was the Judge Advocate for the court.[8] The inquiry found that though Halsey had committed an error of judgment in sailing the Third Fleet into the heart of the typhoon, it stopped short of unambiguously recommending sanction.[9]

In January 1945, Halsey passed command of the Third Fleet to Admiral Spruance (whereupon its designation changed to "Fifth Fleet"). Halsey resumed command in late-May 1945. In early June 1945 Halsey again sailed the fleet into the path of a typhoon, typhoon Connie, and while ships sustained crippling damage, none were lost on this occasion. However six lives were lost, and 75 planes were destroyed, with 70 more badly damaged. A second Navy court of inquiry was convened. This time the court suggested that Halsey be reassigned, but Admiral Nimitz recommended otherwise due to Halsey's prior service to the Navy.[9] Halsey remained in command of Third Fleet until the cessation of hostilities.

See also

- List of Pacific typhoon seasons

- Typhoon Louise, which hit the U.S. fleet off Okinawa October 1945.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center

Notes

- ↑ "Northern Hemisphere Synoptic Weather Map". United States of America Department of Commerce. 1944. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ↑ "Lieutenant Gerald Ford and Typhoon Cobra". Naval Historical Foundation. 7 February 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 Baldwin, Hanson W. Sea Fights and Shipwrecks Hanover House 1956

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Cressman, Robert J. The Official Chronology of the U. S. Navy in World War II Naval Institute Press 2000 ISBN 1-55750-149-1 p.282

- ↑ Pawlowski, Gareth L. Flat-Tops and Fledglings Castle Books 1971 p.233

- ↑ Brown, David Warship Losses of World War II Naval Institute Press 1990 ISBN 1-55750-914-X p.134

- ↑ USS The Sullivans (DD-537)

- ↑ Drury, Bob (2007). Halsey's Typhoon - The True Story of a Fighting Admiral, an Epic Storm and an Untold Rescue. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 978-1-59887-086-2.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Melton, Sea Cobra

References

Printed media

- "How Lieutenant Ford Saved His Ship", New York Times Op-Ed about Typhoon Cobra in December 1944, by Robert Drury and Tom Clavin, authors of Halsey's Typhoon, December 28, 2006.

- Calhoun, C. Raymond. Typhoon, The Other Enemy: The Third Fleet and the Pacific Storm of December, 1944. ©1981.

- Adamson, Hans Christian, and George Francis Kosco. Halsey's Typhoons: A Firsthand Account of How Two Typhoons, More Powerful than the Japanese, Dealt Death and Destruction to Admiral Halsey's Third Fleet. New York: Crown Publishers, 1967.

- Melton, Buckner F., Jr. Sea Cobra: Admiral Halsey's Task Force and the Great Pacific Typhoon. Guilford, Conn.: Lyons Press, 2007.

- Drury, Bob and Tom Clavin. Halsey's Typhoon: The True Story of a Fighting Admiral, an Epic Storm, and an Untold Rescue. Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 2007. (ISBN 0-87113-948-0; ISBN 978-0-87113-948-1).

- Henderson, Bruce (2007). Down to the Sea: An Epic Story of Naval Disaster and Heroism in World War II. Collins. ISBN 0-06-117316-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Typhoon Cobra (1944). |