Two-state quantum system

In quantum mechanics, a two-state system (also known as a two-level system) is a system which can exist in any quantum superposition of two independent (physically distinguishable) quantum states. The Hilbert space describing such a system is two-dimensional. Therefore, a complete basis spanning the space will consist of two independent states.

Two-state systems are the simplest quantum systems that can exist, since the dynamics of a one-state system is trivial (i.e. there is no other state the system can exist in). The mathematical framework required for the analysis of two-state systems is that of linear differential equations and linear algebra of two-dimensional spaces. As a result, the dynamics of a two-state system can be solved analytically without any approximation.

A very well known example of a two-state system is the spin of a spin-1/2 particle such as an electron, whose spin can have values +ħ/2 or −ħ/2, where ħ is the reduced Planck constant. Another example, frequently studied in atomic physics, is the transition of an atom to or from an excited state; here the two-state formalism is used to quantitatively explain stimulated and spontaneous emission of photons from excited atoms.

Representation of the Two-state quantum system

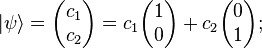

The state of a two-state quantum system can be represented as vectors of a two-dimensional complex Hilbert space, this means every state vector  is represented by two complex coordinates.

is represented by two complex coordinates.

where,

where,  and

and  are the coordinates.[1]

are the coordinates.[1]

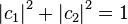

If the vectors are normalized,  and

and  are related by

are related by  . the basis vectors will be represented as

. the basis vectors will be represented as  and

and

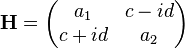

All observable physical quantities associated with this systems are 2  2 Hermitian matrices, this means the Hamiltonian of the system is also a similar matrix.

2 Hermitian matrices, this means the Hamiltonian of the system is also a similar matrix.

The Two-state Hamiltonian

The most general form of the Hamiltonian of a two-state system is given

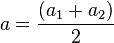

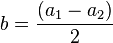

here,  and

and  are real numbers. This matrix can be decomposed as,

are real numbers. This matrix can be decomposed as,

Here,  and

and  are real numbers. The matrix

are real numbers. The matrix  is the 2

is the 2  2 identity matrix and the matrices

2 identity matrix and the matrices  are the Pauli matrices. This decomposition simplifies the analysis of the system especially in the time-independent case where the values of

are the Pauli matrices. This decomposition simplifies the analysis of the system especially in the time-independent case where the values of  and

and  are constants.

are constants.

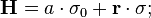

The Hamiltonian can be written (in a slightly different vector form) as:

The vector  is given by

is given by  and

and  is given by

is given by  . This representation simplifies the analysis of the time evolution of the system and is easier to use with other specialized representations such as the Bloch sphere.

. This representation simplifies the analysis of the time evolution of the system and is easier to use with other specialized representations such as the Bloch sphere.

Eigenvalues of the Hamiltonian, Basis vectors and Time evolution

Let  be the time-independent Hamiltonian of a two-state system, the Eigenvalues are given by

be the time-independent Hamiltonian of a two-state system, the Eigenvalues are given by  and the eigenvectors corresponding to them are given as

and the eigenvectors corresponding to them are given as  and

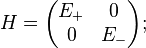

and  corresponding to their respective energies. When one changes the basis to the eigenvectors the Hamiltonian is diagonal and is of the form,

corresponding to their respective energies. When one changes the basis to the eigenvectors the Hamiltonian is diagonal and is of the form,

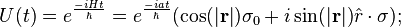

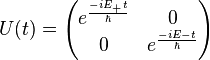

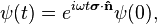

the unitary time evolution operator  is given by:

is given by:

where,  . This is the case when H is in the vector form (i.e. in the

. This is the case when H is in the vector form (i.e. in the  basis); in the eigenvector basis

basis); in the eigenvector basis  is diagonal and is given by:

is diagonal and is given by:

It is to be noted that the  factor only contributes to the overall phase of the operator and can therefore be ignored to yield a new time evolution operator that is physically indistinguishable from the original operator. Moreover, any perturbation to the system (which will be of the same form as the Hamiltonian) can be added to the system in the eigenbasis of the unperturbed Hamiltonian and analysed in the same way as above, this means that for any perturbation the new eigenvectors of the perturbed system can be solved exactly (as mentioned in the introduction).

factor only contributes to the overall phase of the operator and can therefore be ignored to yield a new time evolution operator that is physically indistinguishable from the original operator. Moreover, any perturbation to the system (which will be of the same form as the Hamiltonian) can be added to the system in the eigenbasis of the unperturbed Hamiltonian and analysed in the same way as above, this means that for any perturbation the new eigenvectors of the perturbed system can be solved exactly (as mentioned in the introduction).

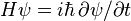

Dynamics of the Two-state System : The Rabi formula

If  is the time-independent Hamiltonian, let

is the time-independent Hamiltonian, let  and

and  denote the two energy eigenstates of the system, with respective eigenvalues

denote the two energy eigenstates of the system, with respective eigenvalues  and

and  . Any state

. Any state  of the two-level system can be written as a superposition of the energy eigenstates; in particular, at time

of the two-level system can be written as a superposition of the energy eigenstates; in particular, at time  we can write,

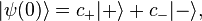

we can write,

the above vector is assumed to be normalized. The time evolution of the state  is given by the relation

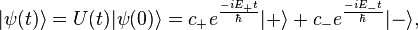

is given by the relation

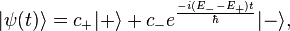

further eliminating an overall phase factor of  the time evolved state can be represented as,

the time evolved state can be represented as,

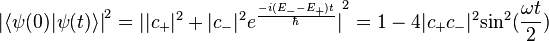

It is easy to infer that if the system was initially in one of the eigestates ( or

or  ) it will continue to remain in the same state, however in a general state as shown above the time evolution is non-trivial. Upon calculating the probability of the state returning to the initial state at a given time

) it will continue to remain in the same state, however in a general state as shown above the time evolution is non-trivial. Upon calculating the probability of the state returning to the initial state at a given time  is given by

is given by

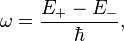

Where  is a characteristic angular frequency given by

is a characteristic angular frequency given by

where it has been assumed that  .[2]

.[2]

It can be seen that the probability of finding the system in its initial quantum state oscillates between  and

and  this formula is called the Rabi oscillation formula. In the case

this formula is called the Rabi oscillation formula. In the case  , that is when the Hamiltonian is degenerate there is no oscillation.

, that is when the Hamiltonian is degenerate there is no oscillation.

Analysis of some important Two-state systems

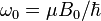

Precession in a field

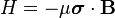

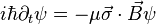

Consider the case of a spin-1/2 particle in a magnetic field  . The interaction Hamiltonian for this system is

. The interaction Hamiltonian for this system is

where  is the magnitude of the particle's magnetic moment and

is the magnitude of the particle's magnetic moment and  is the vector of Pauli matrices. Solving the time dependent Schrödinger equation

is the vector of Pauli matrices. Solving the time dependent Schrödinger equation  yields

yields

where  and

and  . Physically, this corresponds to the Bloch vector precessing around

. Physically, this corresponds to the Bloch vector precessing around  with angular frequency

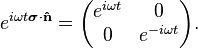

with angular frequency  . Without loss of generality, assume the field is uniform points in

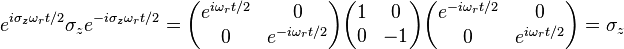

. Without loss of generality, assume the field is uniform points in  , so that the time evolution operator is given as

, so that the time evolution operator is given as

It can be seen that such a time evolution operator acting on a general spin state of a spin-1/2 particle will lead to the precession about the axis defined by the applied magnetic field (this is the quantum mechanical equivalent of Larmor precession)[3]

The above method can however be applied to the analysis of any generic two-state system that is interacting with some field (equivalent to the magnetic filed in the previous case) the interaction is given by an appropriate coupling term thatbis analogous to the magnetic moment. The precession of the state vector (which need not be a physical spinning as in the previous case) can be viewed as the precession of the state vector on the Bloch sphere

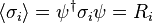

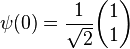

The representation on the Bloch sphere for a state vector  will simply be the vector of expectation values

will simply be the vector of expectation values  . As an example, consider a state vector

. As an example, consider a state vector  that is a normalized superposition of

that is a normalized superposition of  and

and  , that is, a vector that can be represented in the

, that is, a vector that can be represented in the  basis as

basis as

The components of  on the Bloch sphere will simply be

on the Bloch sphere will simply be  . This is a unit vector that begins pointing along

. This is a unit vector that begins pointing along  and precesses around

and precesses around  in a left-handed manner. In general, by a rotation around

in a left-handed manner. In general, by a rotation around  , any state vector

, any state vector  can be represented as

can be represented as  with real coefficients

with real coefficients  and

and  . Such a state vector corresponds to a Bloch vector in the xz-plane making an angle

. Such a state vector corresponds to a Bloch vector in the xz-plane making an angle  with the z-axis. This vector will proceed to precess around

with the z-axis. This vector will proceed to precess around  . In theory, by allowing the system to interact with the field of a particular direction and strength for precise durations, it is possible to obtain any orientation of the Bloch vector, which is equivalent to obtaining any complex superposition. This is the basis for numerous technologies including quantum computing and MRI.

. In theory, by allowing the system to interact with the field of a particular direction and strength for precise durations, it is possible to obtain any orientation of the Bloch vector, which is equivalent to obtaining any complex superposition. This is the basis for numerous technologies including quantum computing and MRI.

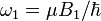

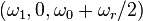

Evolution in a Time-dependent Field: Nuclear magnetic resonance

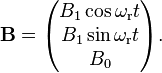

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) is an important example in the dynamics of two-state systems because it is involves the exact solution to a time dependent Hamiltonian. The NMR phenomenon is achieved by placing a nucleus in a strong, static field B0 (the "holding field") and then applying a weak, transverse field B1 that oscillates at some radiofrequency ωr.[4] Explicitly, consider a spin-1/2 particle in a holding field  and a transverse rf field B1 rotating in the xy-plane in a right-handed fashion around B0:

and a transverse rf field B1 rotating in the xy-plane in a right-handed fashion around B0:

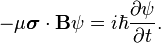

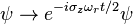

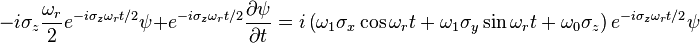

As in the free precession case, the Hamiltonian is  , and the evolution of a state vector

, and the evolution of a state vector  is found by solving the time-dependent Schrödinger equation

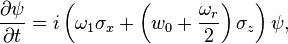

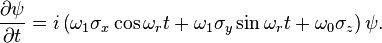

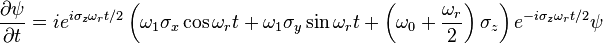

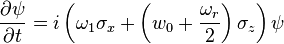

is found by solving the time-dependent Schrödinger equation  . After some manipulation (given in the collapsed section below), it can be shown that the Schrödinger equation becomes

. After some manipulation (given in the collapsed section below), it can be shown that the Schrödinger equation becomes

where  and

and  .

.

As per the previous section, the solution to this equation has the Bloch vector precessing around  with a frequency that is twice the magnitude of the vector. If

with a frequency that is twice the magnitude of the vector. If  is sufficiently strong, some proportion of the spins will be pointing directly down prior to the introduction of the rotating field. If the angular frequency of the rotating magnetic field is chosen such that

is sufficiently strong, some proportion of the spins will be pointing directly down prior to the introduction of the rotating field. If the angular frequency of the rotating magnetic field is chosen such that  , in the rotating frame the state vector will precess around

, in the rotating frame the state vector will precess around  with frequency

with frequency  , and will thus flip from down to up releasing energy in the form of detectable photons. This is the fundamental basis for NMR, and in practice is accomplished by scanning

, and will thus flip from down to up releasing energy in the form of detectable photons. This is the fundamental basis for NMR, and in practice is accomplished by scanning  until the resonant frequency is found at which point the sample will emit light. Similar calculations are done in atomic physics, and in the case that the field is not rotating, but oscillating with a complex amplitude, use is made of the rotating wave approximation in deriving such results.

until the resonant frequency is found at which point the sample will emit light. Similar calculations are done in atomic physics, and in the case that the field is not rotating, but oscillating with a complex amplitude, use is made of the rotating wave approximation in deriving such results.

| Derivation of above expression for the NMR Schrödinger equation |

|---|

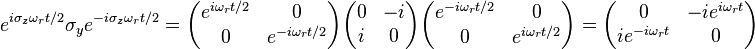

| Here the Schrödinger equation reads

Expanding the dot product and dividing by To remove the time dependence from the problem, the wave function is transformed according to Which after some rearrangement yields Evaluating each term on the right hand side of the equation The equation now reads Which by Euler's identity becomes |

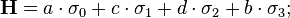

Relation to Bloch equations

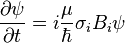

The optical Bloch equations for a collection of spin-1/2 particles can be derived from the time dependent Schrödinger equation for a two level system. Starting with the previously stated Hamiltonian  , it can be written in summation notation after some rearrangement as

, it can be written in summation notation after some rearrangement as

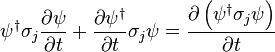

Multiplying by a Pauli matrix  and the conjugate transpose of the wavefunction, and subsequently expanding the product of two Pauli matrices yields

and the conjugate transpose of the wavefunction, and subsequently expanding the product of two Pauli matrices yields

Adding this equation to its own conjugate transpose yields a left hand side of the form

And a right hand side of the form

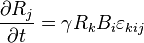

As previously mentioned, the expectation value of each Pauli matrix is a component of the Bloch vector,  . Equating the left and right hand sides, and noting that

. Equating the left and right hand sides, and noting that  is the gyromagnetic ratio

is the gyromagnetic ratio  , yields another form for the equations of motion of the Bloch vector

, yields another form for the equations of motion of the Bloch vector

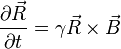

where the fact that  has been used. In vector form these three equations can be expressed in terms of a cross product

has been used. In vector form these three equations can be expressed in terms of a cross product

Classically, this equation describes the dynamics of a spin in a magnetic field. An ideal magnet consists of a collection of identical spins behaving independently, and thus the total magnetization  is proportional to the Bloch vector

is proportional to the Bloch vector  . All that is left to obtain the final form of the optical Bloch equations is the inclusion of the phenomenological relaxation terms.

. All that is left to obtain the final form of the optical Bloch equations is the inclusion of the phenomenological relaxation terms.

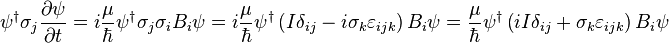

As a final aside, the above equation can be derived by considering the time evolution of the angular momentum operator in the Heisenberg picture.

Which, when coupled with the fact that  , is the same equation as before.

, is the same equation as before.

The Validity of the Two-state formalism

Two-state systems are the simplest non-trivial quantum systems that occur in nature however it should be noted that the above mentioned methods of analysis are not just valid for simple two-state systems. Any general multi-state quantum system can be effectively treated as two-state system as long as a particular property of is being considered (which behaves as a two-state system) an example of this that of a spin-1/2 particle which may have additional translational or even rotational degrees of freedom, however in the preceding analysis, the additional degrees freedom are ignored.

Another case where the effective two-state formalism is valid is when the system under consideration has two levels that are effectively decoupled from the system, this is the case in the analysis of the spontaneous or stimulated emission of light by atoms and that of Charge qubits. In this case it should be kept in mind that the perturbations (interactions with an external field) are in the right range and do not cause transitions to states other than the ones of interest.

Some more examples and the significance of the Two-state formalism

Pedagogically, the two-state formalism is among the simplest of mathematical techniques used for the analysis of quantum systems. The most fundamental quantum mechanical phenomenon such as the interference exhibited by particles of the polarization states of the photon.[5] but also more complex phenomenon such as neutrino oscillation or the neutral K-meson oscillation.

Two-state formalism can be used to describe simple mixing of states which leads to phenomenon such as resonance stabilization and other level crossing related symmetries. Such phenomenon have a wide variety of application in chemistry. Phenomena with tremendous industrial applications such as Maser and laser can be explained using the two-state formalism.

The two-state formalism form the basis of Quantum computing. Qubits which are the building blocks of a Quantum computer are nothing but two-state systems. Any quantum computational operation is a unitary operation that rotates the state vector on the Bloch sphere.

Further reading

- An excellent treatment of the two-state formalism and its application to almost all the applications mentioned in this article is presented in the third volume of The Feynman Lectures on Physics

- The following set of lecture notes covers the necessary mathematics and also treats a few examples in some detail:

- from the Quantum mechanics II course offered at MIT, http://web.mit.edu/8.05/handouts/Twostates_03.pdf

- from the same course dealing with neutral particle oscillation, http://web.mit.edu/8.05/handouts/nukaon_07.pdf

- from the Quantum mechanics I course offered at TIFR, http://theory.tifr.res.in/~sgupta/courses/qm2013/hand4.pdf covers the essential mathematics

- http://theory.tifr.res.in/~sgupta/courses/qm2013/hand5.pdf ; from the same course deals with the some physical two-state systems and other important aspects of the formalism

- the mathematical in the initial section is done in a manner similar to these notes http://www.math.columbia.edu/~woit/QM/qubit.pdf which are form the Quantum Mechanics for Mathematicians course offered at University of Columbia.

- a book version of the same ; http://www.math.columbia.edu/~woit/QM/qmbook.pdf

See also

- Rabi cycle

- Doublet

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

- Quantum Optics

References

- ↑ Griffiths, David (2005). Introduction to Quantum Mechanics (2nd ed.). p. 353.

- ↑ Griffiths, p. 343.

- ↑ Feynman, R.P. (1965). "7-5 and 10-7". The Feynman Lectures on Physics: Volume 3. Addison Wesley.

- ↑ Griffiths, p. 377.

- ↑ Feynman, R.P. (1965). "11-4". The Feynman Lectures on Physics: Volume 3. Addison Wesley.

yields

yields

. The time dependent Schrödinger equation becomes

. The time dependent Schrödinger equation becomes

![i\hbar\frac{d\sigma_j}{dt}=[\sigma_j,H]=[\sigma_j, -\mu \sigma_i B_i]=-\mu\left(\sigma_j\sigma_i B_i - \sigma_i\sigma_j B_i\right)=\mu[\sigma_i,\sigma_j]B_i = 2\mu i \varepsilon_{ijk}\sigma_k B_i](../I/m/1e943bd74fe3207173e677fe1746effd.png)