Twelve-bar blues

The 12-bar blues or blues changes is one of the most prominent chord progressions in popular music. The blues progression has a distinctive form in lyrics, phrase, chord structure, and duration. In its basic form, it is predominantly based on the I-IV-V chords of a key.

The blues can be played in any key. Mastery of the blues and rhythm changes are "critical elements for building a jazz repertoire".[1]

Structure

In the key of C, one basic blues progression, E from above, is as follows.[2]

C C C C or C7 C7 C7 C7 F F C C or F7 F7 C7 C7 G G C C or G7 G7 C7 C7

| Chord | Function | Numerical | Roman numeral |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tonic | T | 1 | I |

| Subdominant | S | 4 | IV |

| Dominant | D | 5 | V |

Chords may be also represented with a few different notation systems. A basic example of the progression would look like this, using T to indicate the tonic, S for the subdominant, and D for the dominant, and representing one chord. In Roman numeral analysis the tonic is called the I, the sub-dominant the IV, and the dominant the V. (These three chords are the basis of thousands more pop songs which thus often have a blues sound even without using the classical 12-bar form.)

Using said notations, the chord progression outlined above can be represented as follows.[3]

|

|

The first line takes four bars, as do the remaining two lines, for a total of twelve bars. However, the vocal or lead phrases, though they often come in threes, do not coincide with the above three lines or sections. This overlap between the grouping of the accompaniment and the vocal is part of what creates interest in the twelve bar blues.

Variations

"W.C. Handy, 'the Father of the Blues,' codified this blues form to help musicians communicate chord changes."[4] However, many variations are possible. The length of sections may be varied to create eight-bar blues or sixteen-bar blues.

In the original form, the dominant chord continued through the tenth bar; later on the V-IV-I-I "shuffle blues" pattern became standard in the third set of four bars:[5]

- {| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center; width:110px;"

|--

|width=25%|I

|width=25%|I

|width=25%|I

|width=25%|I

|--

| IV ||IV ||I ||I

|--

| V ||IV ||I ||I

|--

|}![]() Play

Play

The common quick to four or quick-change (quick four[6]) variation uses the subdominant chord in the second bar:

|

These variations are not mutually exclusive; the rules for generating them may be combined with one another (and/or with others not listed) to generate more complex variations.

Seventh chords are often used just before a change, and more changes can be added. A more complicated example might look like this, where "7" indicates a seventh chord:

Using a seventh chord I IV I I7 IV IV7 I I7 V IV I V7

When the last bar contains the dominant, that bar may be called a turnaround, otherwise the last four measures is the blues turnaround.

- {|class="wikitable" style="text-align:center; width:250px;"

|width=25%|I7

|width=25%|IV7 IVo

|width=25%|I7

|width=25%|v7 I7

|--

| IV7 || IVo || I7 || III7 VI7

|--

| ii7 || V7 || III7 VI7 || II7 V7

|--

|}![]() Play

Play

In jazz, 12-bar blues progressions are expanded with moving substitutions and chordal variations. The cadence (or last four measures) uniquely leads to the root by perfect intervals of fourths.

The Bebop blues:[7]

- {| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center; width:250px;"

|--

|width=25%|I7

|width=25%|IV7

|width=25%|I7

|width=25%|v7 I7

|--

| IV7 ||♯IVo7 ||I7 ||V/ii♭9

|--

| ii7 ||V7 ||I7 V/ii♭9 ||ii7 V7

|--

|}![]() Play

Play

This progression is similar to Charlie Parker's "Now's the Time", "Billie's Bounce", Sonny Rollins's "Tenor Madness", and many other bop tunes.[8] "It is a bop soloist's cliche to arpeggiate this chord [A7♭9 (V/ii = VI7♭9)] from the 3 up to the ♭9."[9]

- {| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center; width:110px;"

|width=25%|i7

|width=25%|i7

|width=25%|i7

|width=25%|i7

|--

| iv7 ||iv7 ||i7 ||i7

|--

| ♭VI7 ||V7 ||i7 ||i7

|--

|}![]() Play

Play

There are also minor 12-bar blues, such as John Coltrane's "Equinox" and "Mr. P.C.",[10] and "Why Don't You Do Right?", made famous by Lil Green with Big Bill Broonzy and then Peggy Lee with the Benny Goodman Orchestra. The chord on the fifth scale degree may be major, V7, or minor, v7, in which case it fits a dorian scale along with the minor i7 and iv7 chords, creating a modal feeling.[11] Major and minor can also be mixed together, a signature characteristic of the music of Charles Brown.

While the blues is most often considered to be in sectional strophic form with a verse-chorus pattern, it may also be considered as an extension of the variational chaconne procedure. Van der Merwe (1989) considers it developed in part specifically from the American Gregory Walker though the conventional account would consider hymns as the provider of the blues repeating chord progression or harmonic formulae.[12]

Lyrical patterns

Most commonly, lyrics are in three lines, with the first two lines almost the same with slight differences in phrasing and interjections.

- I hate to see the evening sun go down,

- Yes, I hate to see that evening sun go down

- 'Cause it makes me think I'm on my last go 'round

- W. C. Handy's "St. Louis Blues"

However, many songs exist that are written in the blues chord progression do not use the three-line form of lyrics. For instance, "I'm Moving On" has a verse in the first four bars and a chorus in the final eight bars:

- That big eight-wheeler rollin' down the track

- Means your true lovin' daddy ain't comin' back.

- I'm movin' on, I'll soon be gone

- You were flyin' too high for my little old sky

- So I'm movin' on.

Here is an example showing the 12 bar blues pattern and how it fits with the lyrics of a given verse. One chord symbol is used per beat, with "-" representing the continuation of the previous chord:

- I - - - IV - - - I - - - I7 - - -

- Woke up this morning with an awful aching head

- IV - - - IV7 - - - I - - - I7 - - -

- Woke up this morning with an awful aching head

- V - - V7 IV - - IV7 I - - - I - V V7

- My new man had left me, just a room and an empty bed.

- From Bessie Smith's "Empty Bed Blues".

Another example, "Johnny B. Goode" (written and first recorded by Chuck Berry), applies a "shuffle" or "light 'swing'" rhythm to one of the more common twelve-bar progressions:

| Line | Pickup | Measure 1 | Measure 2 | Measure 3 | Measure 4' | ||||

| 1 | Deep | Bb (I) | down in Lou'siana, close to | Bb (I) | New Orleans, way | Bb (I) | back up in the woods among the | Bb (I) | evergreens, |

| 2 | There | Eb (IV) | stood a log cabin, made from | Eb (IV) | earth and wood, where | Bb (I) | lived a country boy named | Bb (I) | Johnny B. Goode. |

| 3 | He | F (V) | never really learned to read or | F7 (V7) | write too well, but he could | Bb (I) | play a guitar just like a- | Bb (I) | -ringin' a bell. |

Another progression, D-D7-G7-A7, appears in this collection (Axelsson & Strängliden 2007, 55).

"Twelve-bar" examples

The 12-bar blues chord progression is the basis of thousands of songs, not only formally identified blues songs. The vast majority of boogie-woogie compositions are 12-bar blues, as are many early rock songs.[13]

- Ray Charles' "What'd I Say" (1959) makes use of the twelve-bar blues progression. Other popular examples of twelve bar blues include:

- Rock Around the Clock (1952)

- Muddy Waters' "Train Fare Blues" (1948)

- Howlin' Wolf's "Evil" (1954)

- Big Joe Turner's "Shake, Rattle, and Roll" (1954).[14]

- Nappy Brown's Night Time is the Right Time (1957), made famous by Ray Charles

- Henry Mancini's "Baby Elephant Walk" (1961).

- The Surfari's "Wipeout" (1963).

- James Brown's Night Train (1966).

- The refrain of Duffy's 2011 "Mercy"

- Gene Vincent's "Be Bop A Lula"

- Elvis Presley's "Hound Dog" and the "A" section of "All Shook Up." "Heartbreak Hotel" is a diminution of the 12-bar blues.

- Several Beatles songs by Lennon & McCartney, including Can't Buy Me Love, Day Tripper, the verse structure of "I Want You (She's So Heavy)", and more obvious blues songs like "Why Don't We Do It In the Road," "(They Say It's) Your Birthday," "For You Blue," and "Yer Blues"

- Louis Prima's "Jump, Jive and Wail"

- Johnny Cash's "Folsom Prison Blues"

- King Oliver Creole's "Dippermouth Blues"

- Mungo Jerry's "In the Summertime"

- Little Richard's "Tutti Fruttii"

- White Stripes' "Ball and Biscuit"

- ZZ Top single "Tush" is an example of the twelve-bar blues in rock.

- Prince's "Kiss" is a 12-bar blues form with unusually long 8-beat bars.

- Georgia Satellites' "Keep Your Hands to Yourself"

- Stevie Ray Vaughan's "Pride and Joy"

- Led Zeppelin's "The Girl I Love She Got Long Black Wavy Hair" and their cover of "You Shook Me" and "Traveling Riverside Blues".

- Tracy Chapman's "Give Me One Reason"

- Batman (TV series) theme song "Batman Theme", by Neal Hefti

Examples of altered or extended progressions include Herbie Hancock's "Watermelon Man".[15]

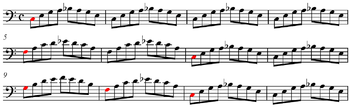

You may also find many improvised versions of this piece, often seen in piano practice books, and as simple tunes to try out a musical instrument, such as this one, played in the C key. ![]() Play

Play

Analysis

The twelve-bar blues, a chromatic chord progression, is a logical formula for blues music: without the dominant's major minor seventh chord (in C: G7), the sequence does not accord with the tonal "V-I" relationship. Instead, it would be based mostly on a plagal cadence—an IV-I change (in C: F-C). The key is fully verified with the V7 (G7) chord,[16] but only after going over the subdominant (F) and tonic (C).

Additionally, the chord progression meshes elements of major and minor. The major-minor (dominant) seventh chords used on each degree alone seem to fall in some grey area between the strong, content major chord and the somber, conflicted minor chord. The subdominant's seventh chord is of note here, because of its odd relationship with the tonic.

In classical music, the dominant (major-minor) seventh chord on the tonic would almost certainly resolve elsewhere (rather than being resolved to), especially its subdominant (from C7: to F). While, at first it seems to resolve well to the subdominant, this is merely a tonicization (brief leave to another key), because of the earlier emphasis on the dominant seventh (C7), and because of the dominant seventh that appears on the subdominant, an element found in the Dorian mode. Traditionally, the seventh of the subdominant chord would not be flattened, as it would contradict the third of the tonic chord. This undermines the expected resolution and also questions whether the actual tonic is major or minor in quality: this seventh chord (F-A-C-E♭) resolves back to the tonic by resolving both up a step to ![]() (E♭-->E) (mediant), and down a step to

(E♭-->E) (mediant), and down a step to ![]() from

from ![]() (F-->E) (leading tone); and down harmonically to I.

(F-->E) (leading tone); and down harmonically to I.

When returning to the I7 chord, the major third sounds like a Picardy third resolution, and the minor seventh no longer seems to resolve to the sixth (B♭-->A, the third of IV; instead it seems like a blue note that adds a tense, funky, thick color to the tonic.

In jazz

Jazz is considered to have some of its roots in the blues,[17] and the blues progression is one of several blues elements found in jazz such as blue notes, blues-like phrasing of melodies, and blues riffs. Tunes that utilize the jazz-blues harmony are fairly common in the jazz repertoire, especially from the bebop era.

A twelve-bar jazz blues will usually feature a more sophisticated—or at any rate a different—treatment of the harmony than a traditional blues would, but the underlying features of the standard 12-bar blues progression remain discernible. One of the main ways the jazz musician accomplishes this is through the use of chord substitutions—a chord in the original progression is replaced by one or more chords which have the same general "sense" or function; in this case occurring especially in the turnaround (i.e., the last four bars). One well-known artist that sang this form of jazz was Billie Holiday, and almost all well known instrumental jazz musicians will have recorded at least one variation on this theme.

The 12-bar blues form, in the commonly played key of B♭, often becomes:

Bb7 / Eb7 / Bb7 / Bb7 / Eb7 / Edim7 / Bb7 / Dm7 - G7 / Cm7 / F7 / Dm7 - G7 / Cm7 - F7 //

Transposed to the key of C:

C7 / F7 / C7 / C7 / F7 / F♯dim7 / C7 / Em7 - A7 / Dm7 / G7 / Em7 - A7 / Dm7 - G7 //

where each slash represents a new measure, in the jazz-blues. The significant changes include the Edim7, which creates movement, and the III-VI-II-V or I-VI-II-V turnaround, a jazz staple.

There is however no standard form of jazz blues, and several common variations. For example, the diminished chord in bar 6 is often omitted, and many turnarounds are possible. An example turnaround using chromatic chord movement could be:

Dm7 / G7 / C7 - Eb7 / D7 - Db7

Another variation has the cycle concluding on the dominant chord as in a standard blues. This feature introduces a tension that propels the listener's expectation toward the next chord change cycle. Here is an example:

C7 - A7 / Dm7 - G7

Count Basie's version of the blues progression, which came into wide use, demonstrates several of these variations (shown here in the key of F):

F7 / Bb7 Bdim / F7 / Cm7 F7 / Bb7 / Bdim / F7 / D7 / Gm7 / C7 / F7 / Gm7 C7 /

Alto sax great Charlie Parker introduced a fluid chord sequence for jazz blues, using tritone substitution and chromatic chord changes typical of the be-bop era. It has come to be known as Bird Blues, after his nickname, "Yardbird," or more simply, "Bird."

- {|class="wikitable" style="text-align:center; width:250px;"

|width=25%|I7

|width=25%|vii7♭5 III7♭9

|width=25%|vi7 II7

|width=25%|v7 I7

|-

| IV7 || iv7 ♭VII7 || iii7 VI7 || ♭III7 ♭VI7

|-

| ii7 || V7 || I7 VI7♭9 || ii7 V7

|-

|}![]() Play

Play

For example, similar progressions may be found in, Parker's "Blues for Alice", Wes Montgomery's "West Coast Blues", and the non-jazz Toots Thielemans' "Bluesette", Parker's "Confirmation", and Harry Warren's "There Will Never Be Another You".[19] Below is a common version of the Bird Blues chord sequence, shown here in F:

Fmaj7 / Em7b5 A7b9 / Dm7 Db7 / Cm7 F7 / Bb7 / Bbm7 Eb7 / Am7 D7 / Abm7 Db7 / Gm7 / C7 / F D7 / Gm7 C7 //

A more modern example is the A-section of Pat Metheny's "Missouri Uncompromised". The first 4 bars and the last 4 bars are taken from the classic blues (albeit without the dominant quality); the middle 4 bars, although completely altered, still follow the functional pattern of the blues:

- B♭/A is a suspended subdominant, which serves as a pivot point modulating to B♭ major, where it becomes an unstable form of the tonic;

- D♭/A♭ serves as a more stable version of a (now minor) tonic substitute (tonic of the subdominant is subdominant by association to the original key);

- E♭/G serves as a pivot point modulating back to A major, where it becomes the tritone substitute of the tonic;

- D/F♯ and Dm/F are both subdominant, creating a natural movement from the tonic substitute above to the dominant chord in bar 9.

A / A / A / A / Bb/A / Db/Ab / Eb/G / D/F# Dm/F / E / D / A / A //

See also

- List of jazz blues musicians

- Blues ballad

- Talking blues

- Thirty-two-bar form

- 50s progression, another popular chord progression in Western popular music.

- 12-Bar Original

References

- ↑ Thomas 2002, p. 85.

- ↑ Benward & Saker 2003, p. 186.

- ↑ Kernfeld 2007

- ↑ Alfred Publishing, p. 18

- ↑ Tanner and Gerow 1984, p. 37 cited in Baker 2004: "This alteration [V-IV-I rather than V-V-I] is now considered standard."

- ↑ Alfred 2003, p. 4

- ↑ Spitzer 2001, p. 62

- ↑ Spitzer 2001, p. 62.

- ↑ Spitzer 2001, p. 62.

- ↑ Spitzer 2001, p. 63.

- ↑ Spitzer 2001, p. 63.

- ↑ Middleton 1990, pp. 117–8).

- ↑ Doll 2009, p. 22.

- ↑ Covach 2005, p. 67.

- ↑ Spitzer 2001, p. 64.

- ↑ http://kkguitar.com/all-blues/12-bar-blues

- ↑ Shipton 2007, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Spitzer 2001, p. 64.

- ↑ Spitzer 2001, p. 64.

Works cited

- Alfred Publishing (2002). Beginning Delta Blues Guitar. ISBN 978-0-7390-3006-6.

- Alfred Publishing (2003). Electric Bass for Guitarists. ISBN 0-7390-3335-2.

- Anonymous (8-14-08). "Blues Chord Progressions and Variations: Common variations in the twelve bar form", How to Play Blues Guitar.com.

- Axelsson, Lars; Strängliden, Eddie, eds. (2007). "Johnny B. Goode". 100 Lätta Låtar: Gitarr [100 Easy Songs: Guitar]. 100 Lätta Låtar 1. Erhrlingförlagen AB. ISBN 978-91-85662-11-1.

- Benward, Bruce, and Marilyn Nadine Saker (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. I, seventh edition. Boston: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- Covach, John. "Form in Rock Music: A Primer", in Stein, Deborah (2005). Engaging Music: Essays in Music Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517010-5.

- Doll, Christopher (2009). "Transformation in Rock Harmony: An Explanatory Strategy". Gamut (2): 1–44.

- Gerow, Maurice and Tanner, Paul (1984). A Study of Jazz, Dubuque, Iowa: William C. Brown Publishers, p. 37, cited in Baker, Robert M. (2005). A Brief History of the Blues".

- Kernfeld, Barry, ed. (2007). "Blues progression". The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz;. 2nd Edition. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Middleton, Richard (1990/2002). Studying Popular Music. Philadelphia: Open University Press. ISBN 0-335-15275-9.

- Shipton, Alyn (2007). A New History of Jazz, 2nd. ed., Continuum, pp. 4–5.

- Spitzer, Peter (2001). Jazz Theory Handbook. ISBN 978-0-7866-5328-7.

- Thomas, John (2002). Voice Leading for Guitar: Moving Through the Changes. ISBN 0-634-01655-5.

- van der Merwe, Peter (1989). Origins of the Popular Style. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-316121-4. Cited in Middleton (1990).

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||