Tweedie distribution

In probability and statistics, the Tweedie distributions are a family of probability distributions which include the purely continuous normal and gamma distributions, the purely discrete scaled Poisson distribution, and the class of mixed compound Poisson–gamma distributions which have positive mass at zero, but are otherwise continuous.[1] For any random variable Y that obeys a Tweedie distribution, the variance var(Y) relates to the mean E(Y) by the power law,

where a and p are positive constants.

The Tweedie distributions were named by Bent Jørgensen[2] after Maurice Tweedie, a statistician and medical physicist at the University of Liverpool, UK, who presented the first thorough study of these distributions in 1984.[1][3]

Examples

The Tweedie distributions include a number of familiar distributions as well as some unusual ones, each being specified by the domain of the index parameter. We have the

- normal distribution, p = 0,

- Poisson distribution, p = 1,

- compound Poisson–gamma distribution, 1 < p < 2,

- gamma distribution, p = 2,

- positive stable distributions, 2 < p < 3,

- inverse Gaussian distribution, p = 3,

- positive stable distributions, p > 3, and

- extreme stable distributions, p = ∞.

For 0 < p < 1 no Tweedie model exists.

Definitions

Tweedie distributions are a special case of exponential dispersion models, a class of models used to describe error distributions for the generalized linear model.[4] The term exponential dispersion model refers to the exponential form that these models take, evident from the canonical equation used to describe the distribution Pλ,θ of the random variable Z on the measurable sets A,

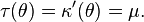

with the interrelated measures νλ. θ is the canonical parameter; the cumulant function is

λ is the index parameter; and z the canonical statistic. This equation represents a family of exponential dispersion models ED*(θ,λ) that are completely determined by the parameters θ and λ and the cumulant function.

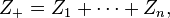

Additive exponential dispersion models

The models just described are additive models with the property that the distribution of the sum of independent random variables,

for which Zi ~ ED*(θ,λi) with fixed θ and various λ are members of the family of distributions with the same θ,

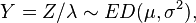

Reproductive exponential dispersion models

A second class of exponential dispersion models exists designated by the random variable

where σ2 = 1/λ, known as reproductive exponential dispersion models. They have the property that for n independent random variables Yi ~ ED(μ,σ2/wi), with weighting factors wi and

a weighted average of the variables gives,

For reproductive models the weighted average of independent random variables with fixed μ and σ2 and various values for wi is a member of the family of distributions with same μ and σ2.

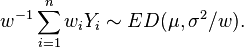

The Tweedie exponential dispersion models are both additive and reproductive; we thus have the duality transformation

Scale invariance

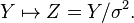

A third property of the Tweedie models is that they are scale invariant: For a reproductive exponential dispersion model ED(μ,σ2) and any positive constant c we have the property of closure under scale transformation,

where the index parameter p is a real-valued unitless constant. With this transformation the new variable Y’ = cY belongs to the family of distributions with fixed μ and σ2 but different values of c.

The Tweedie power variance function

To define the variance function for exponential dispersion models we make use of the mean value mapping, the relationship between the canonical parameter θ and the mean μ. It is define by the function

The variance function V(μ) is constructed from the mean value mapping,

Here the minus exponent in τ−1(μ) denotes an inverse function rather than a reciprocal. The mean and variance of an additive random variable is then E(Z) = λμ and var(Z)=λV(μ).

Scale invariance implies that the variance function obeys the relationship V(μ) = μ p.[4]

The Tweedie cumulant generating functions

The properties of exponential dispersion models give us two differential equations.[4] The first relates the mean value mapping and the variance function to each other,

The second shows how the mean value mapping is related to the cumulant function,

These equations can be solved to obtain the cumulant function for different cases of the Tweedie models. A cumulant generating function (CGF) may then be obtained from the cumulant function. The additive CGF is generally specified by the equation

and the reproductive CGF by

where s is the generating function variable.

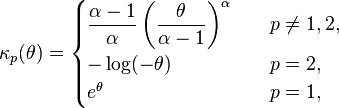

The cumulant functions for specific values of the index parameter p are[4]

where α is the Tweedie exponent

For the additive Tweedie models the CGFs take the form,

and for the reproductive models,

The additive and reproductive Tweedie models are conventionally denoted by the symbols Tw*p(θ,λ) and Twp(θ,σ2), respectively.

The first and second derivatives of the CGFs, with s = 0, yields the mean and variance, respectively. One can thus confirm that for the additive models the variance relates to the mean by the power law,

The Tweedie convergence theorem

The Tweedie exponential dispersion models are fundamental in statistical theory consequent to their roles as foci of convergence for a wide range of statistical processes. Jørgensen et al proved a theorem that specifies the asymptotic behaviour of variance functions known as the Tweedie convergence theorem".[5] This theorem, in technical terms, is stated thus:[4] The unit variance function is regular of order p at zero (or infinity) provided that V(μ) ~ c0μp for μ as it approaches zero (or infinity) for all real values of p and c0 > 0. Then for a unit variance function regular of order p at either zero or infinity and for

for any  , and

, and  we have

we have

as  or

or  , respectively, where the convergence is through values of c such that cμ is in the domain of θ and cp−2/σ2 is in the domain of λ. The model must be infinitely divisible as c2−p approaches infinity.[4]

, respectively, where the convergence is through values of c such that cμ is in the domain of θ and cp−2/σ2 is in the domain of λ. The model must be infinitely divisible as c2−p approaches infinity.[4]

In nontechnical terms this theorem implies that any exponential dispersion model that asymptotically manifests a variance-to-mean power law is required to have a variance function that comes within the domain of attraction of a Tweedie model. Almost all distribution functions with finite cumulant generating functions qualify as exponential dispersion models and most exponential dispersion models manifest variance functions of this form. Hence many probability distributions have variance functions that express this asymptotic behavior, and the Tweedie distributions become foci of convergence for a wide range of data types.[6]

The Tweedie models and Taylor’s power law

Taylor's law is an empirical law in ecology that relates the variance of the number of individuals of a species per unit area of habitat to the corresponding mean by a power-law relationship.[7] For the population count Y with mean µ and variance var(Y), Taylor’s law is written,

where a and p are both positive constants. Since L. R. Taylor described this law in 1961 there have been many different explanations offered to explain it, ranging from animal behavior,[7] a random walk model,[8] a stochastic birth, death, immigration and emigration model,[9] to a consequence of equilibrium and non-equilibrium statistical mechanics.[10] No consensus exists as to an explanation for this model.

Since Taylor’s law is mathematically identical to the variance-to-mean power law that characterizes the Tweedie models, it seemed reasonable to use these models and the Tweedie convergence theorem to explain the observed clustering of animals and plants associated with Taylor’s law.[11][12] The majority of the observed values for the power-law exponent p have fallen in the interval (1,2) and so the Tweedie compound Poisson–gamma distribution would seem applicable. Comparison of the empirical distribution function to the theoretical compound Poisson–gamma distribution has provided a means to verify consistency of this hypothesis.[11]

Whereas conventional models for Taylor’s law have tended to involve ad hoc animal behavioral or population dynamic assumptions, the Tweedie convergence theorem would imply that Taylor’s law results from a general mathematical convergence effect much as how the central limit theorem governs the convergence behavior of certain types of random data. Indeed, any mathematical model, approximation or simulation that is designed to yield Taylor’s law (on the basis of this theorem) is required to converge to the form of the Tweedie models.[6]

Tweedie convergence and 1/f noise

Pink noise, or 1/f noise, refers to a pattern of noise characterized by a power-law relationship between its intensities S(f) at different frequencies f,

where the dimensionless exponent γ ∈ [0,1]. It is found within a diverse number of natural processes.[13] Many different explanations for 1/f noise exist, a widely held hypothesis is based on Self-organized criticality where dynamical systems close to a critical point are thought to manifest scale-invariant spatial and/or temporal behavior.

In this subsection a mathematical connection between 1/f noise and the Tweedie variance-to-mean power law will be described. To begin, we first need to introduce self-similar processes: For the sequence of numbers

with mean

deviations

variance

and autocorrelation function

with lag k, if the autocorrelation of this sequence has the long range behavior

as k→∞ and where L(k) is a slowly varying function at large values of k, this sequence is called a self-similar process.[14]

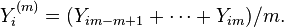

The method of expanding bins can be used to analyze self-similar processes. Consider a set of equal-sized non-overlapping bins that divides the original sequence of N elements into groups of m equal-sized segments (N/m is integer) so that new reproductive sequences, based on the mean values, can be defined:

The variance determined from this sequence will scale as the bin size changes such that

if and only if the autocorrelation has the limiting form[15]

One can also construct a set of corresponding additive sequences

based on the expanding bins,

Provided the autocorrelation function exhibits the same behavior, the additive sequences will obey the relationship

Since  and

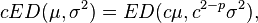

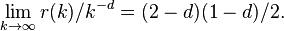

and  are constants this relationship constitutes a variance-to-mean power law, with p = 2 - d.[6][16]

are constants this relationship constitutes a variance-to-mean power law, with p = 2 - d.[6][16]

The biconditional relationship above between the variance-to-mean power law and power law autocorrelation function, and the Wiener–Khinchin theorem[17] imply that any sequence that exhibits a variance-to-mean power law by the method of expanding bins will also manifest 1/f noise, and vice versa. Moreover, the Tweedie convergence theorem, by virtue of its central limit-like effect of generating distributions that manifest variance-to-mean power functions, will also generate processes that manifest 1/f noise.[6] The Tweedie convergence theorem thus allows provides an alternative explanation for the origin of 1/f noise, based its central limit-like effect.

Much as the central limit theorem requires certain kinds of random processes to have as a focus of their convergence the Gaussian distribution and thus express white noise, the Tweedie convergence theorem requires certain non-Gaussian processes to have as a focus of convergence the Tweedie distributions that express 1/f noise.[6]

The Tweedie models and multifractality

From the properties of self-similar processes, the power-law exponent p = 2 - d is related to the Hurst exponent H and the fractal dimension D by[15]

A one-dimensional data sequence of self-similar data may demonstrate a variance-to-mean power law with local variations in the value of p and hence in the value of D. When fractal structures manifest local variations in fractal dimension, they are said to be multifractals. Examples of data sequences that exhibit local variations in p like this include the eigenvalue deviations of the Gaussian Orthogonal and Unitary Ensembles.[6] The Tweedie compound Poisson–gamma distribution has served to model multifractality based on local variations in the Tweedie exponent α. Consequently, in conjunction with the variation of α, the Tweedie convergence theorem can be viewed as having a role in the genesis of such multifractals.

The variation of α has been found to obey the asymmetric Laplace distribution in certain cases.[18] This distribution has been shown to be a member of the family of geometric Tweedie models,[19] that manifest as limiting distributions in a convergence theorem for geometric dispersion models.

Applications

Regional organ blood flow

Regional organ blood flow has been traditionally assessed by the injection of radiolabelled polyethylene microspheres into the arterial circulation of animals, of a size that they become entrapped within the microcirculation of organs. The organ to be assessed is then divided into equal-sized cubes and the amount of radiolabel within each cube is evaluated by liquid scintillation counting and recorded. The amount of radioactivity within each cube is taken to reflect the blood flow through that sample at the time of injection. It is possible to evaluate adjacent cubes from an organ in order to additively determine the blood flow through larger regions. Through the work of J B Bassingthwaighte and others an empirical power law has been derived between the relative dispersion of blood flow of tissue samples (RD = standard deviation/mean) of mass m relative to reference-sized samples:[20]

This power law exponent Ds has been called a fractal dimension. Bassingthwaighte’s power law can be shown to directly relate to the variance-to-mean power law. Regional organ blood flow can thus be modelled by the Tweedie compound Poisson–gamma distribution.,[21] In this model tissue sample could be considered to contain a random (Poisson) distributed number of entrapment sites, each with gamma distributed blood flow. Blood flow at this microcirculatory level has been observed to obey a gamma distribution,[22] thus providing support for this hypothesis.

Cancer metastasis

The "experimental cancer metastasis assay"[23] has some resemblance to the above method to measure regional blood flow. Groups of syngeneic and age matched mice are given intravenous injections of equal-sized aliquots of suspensions of cloned cancer cells and then after a set period of time their lungs are removed and the number of cancer metastases enumerated within each pair of lungs. If other groups of mice are injected with different cancer cell clones then the number of metastases per group will differ in accordance with the metastatic potentials of the clones. It has been long recognized that there can be considerable intraclonal variation in the numbers of metastases per mouse despite the best attempts to keep the experimental conditions within each clonal group uniform.[23] This variation is larger than would be expected on the basis of a Poisson distribution of numbers of metastases per mouse in each clone and when the variance of the number of metastases per mouse was plotted against the corresponding mean a power law was found.[24]

The variance-to-mean power law for metastases was found to also hold for spontaneous murine metastases[25] and for cases series of human metastases.[26] Since hematogenous metastasis occurs in direct relationship to regional blood flow[27] and videomicroscopic studies indicate that the passage and entrapment of cancer cells within the circulation appears analogous to the microsphere experiments[28] it seemed plausible to propose that the variation in numbers of hematogenous metastases could reflect heterogeneity in regional organ blood flow.[29] The blood flow model was based on the Tweedie compound Poisson–gamma distribution, a distribution governing a continuous random variable. For that reason in the metastasis model it was assumed that blood flow was governed by that distribution and that the number of regional metastases occurred as a Poisson process for which the intensity was directly proportional to blood flow. This lead to the description of the Poisson negative binomial (PNB) distribution as a discrete equivalent to the Tweedie compound Poisson–gamma distribution. The probability generating function for the PNB distribution is

The relationship between the mean and variance of the PNB distribution is then

which, in the range of many experimental metastasis assays, would be indistinguishable from the variance-to-mean power law. For sparse data, however, this discrete variance-to-mean relationship would behave more like that of a Poisson distribution where the variance equaled the mean.

Genomic structure and evolution

The local density of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) within the human genome, as well as that of genes, appears to cluster in accord with the variance-to-mean power law and the Tweedie compound Poisson–gamma distribution.[30][31] In the case of SNPs their observed density reflects the assessment techniques, the availability of genomic sequences for analysis, and the nucleotide heterozygosity.[32] The first two factors reflect ascertainment errors inherent to the collection methods, the latter factor reflects an intrinsic property of the genome.

In the coalescent model of population genetics each genetic locus has its own unique history. Within the evolution of a population from some species some genetic loci could presumably be traced back to a relatively recent common ancestor whereas other loci might have more ancient genealogies. More ancient genomic segments would have had more time to accumulate SNPs and to experience recombination. R R Hudson has proposed a model where recombination could cause variation in the time to most common recent ancestor for different genomic segments.[33] A high recombination rate could cause a chromosome to contain a large number of small segments with less correlated genealogies.

Assuming a constant background rate of mutation the number of SNPs per genomic segment would accumulate proportionately to the time to the most recent common ancestor. Current population genetic theory would indicate that these times would be gamma distributed, on average.[34] The Tweedie compound Poisson–gamma distribution would suggest a model whereby the SNP map would consist of multiple small genomic segments with the mean number of SNPs per segment would be gamma distributed as per Hudson’s model.

The distribution of genes within the human genome also demonstrated a variance-to-mean power law, when the method of expanding bins was used to determine the corresponding variances and means.[31] Similarly the number of genes per enumerative bin was found to obey a Tweedie compound Poisson–gamma distribution. This probability distribution was deemed compatible with two different biological models: the microarrangement model where the number of genes per unit genomic length was determined by the sum of a random number of smaller genomic segments derived by random breakage and reconstruction of protochormosomes. These smaller segments would be assumed to carry on average a gamma distributed number of genes.

In the alternative gene cluster model, genes would be distributed randomly within the protochromosomes. Over large evolutionary timescales there would occur tandem duplication, mutations, insertions, deletions and rearrangements that could affect the genes through a stochastic birth, death and immigration process to yield the Tweedie compound Poisson–gamma distribution.

Both these mechanisms would implicate neutral evolutionary processes that would result in regional clustering of genes.

Random matrix theory

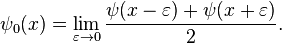

The Gaussian unitary ensemble (GUE) consists of complex Hermitian matrices that are invariant under unitary transformations whereas the Gaussian orthogonal ensemble (GOE) consists of real symmetric matrices invariant under orthogonal transformations. The ranked eigenvalues En from these random matrices obey Wigner’s semicircular distribution: For a N×N matrix the average density for eigenvalues of size E will be

as E→ ∞ . Integration of the semicircular rule provides the number of eigenvalues on average less than E,

The ranked eigenvalues can be unfolded, or renormalized, with the equation

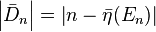

This removes the trend of the sequence from the fluctuating portion. If we look at the absolute value of the difference between the actual and expected cumulative number of eigenvalues

we obtain a sequence of eigenvalue fluctuations which, using the method of expanding bins, reveals a variance-to-mean power law.[6] The eigenvalue fluctuations of both the GUE and the GOE manifest this power law with the power law exponents ranging between 1 and 2, and they similarly manifest 1/f noise spectra. These eigenvalue fluctuations also correspond to the Tweedie compound Poisson–gamma distribution and they exhibit multifractality.[6]

The distribution of prime numbers

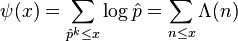

The second Chebyshev function ψ(x) is given by,

where the summation extends over all prime powers  not exceeding x, x runs over the positive real numbers, and

not exceeding x, x runs over the positive real numbers, and  is the von Mangoldt function. The function ψ(x) is related to the prime-counting function π(x), and as such provides information with regards to the distribution of prime numbers amongst the real numbers. It is asymptotic to x, a statement equivalent to the prime number theorem and it can also be shown to be related to the zeros of the Riemann zeta function located on the critical strip ρ, where the real part of the zeta zero ρ is between 0 and 1. Then ψ expressed for x greater than one can be written:

is the von Mangoldt function. The function ψ(x) is related to the prime-counting function π(x), and as such provides information with regards to the distribution of prime numbers amongst the real numbers. It is asymptotic to x, a statement equivalent to the prime number theorem and it can also be shown to be related to the zeros of the Riemann zeta function located on the critical strip ρ, where the real part of the zeta zero ρ is between 0 and 1. Then ψ expressed for x greater than one can be written:

where

The Riemann hypothesis states that the nontrivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function all have real part ½. These zeta function zeros are related to the distribution of prime numbers. Schoenfeld[35] has shown that if the Riemann hypothesis is true then

for all  . If we analyze the Chebyshev deviations Δ(n) on the integers n using the method of expanding bins and plot the variance versus the mean a variance to mean power law can be demonstrated.[36] Moreover, these deviations correspond to the Tweedie compound Poisson-gamma distribution and they exhibit 1/f noise.

. If we analyze the Chebyshev deviations Δ(n) on the integers n using the method of expanding bins and plot the variance versus the mean a variance to mean power law can be demonstrated.[36] Moreover, these deviations correspond to the Tweedie compound Poisson-gamma distribution and they exhibit 1/f noise.

Other applications

Applications of Tweedie distributions include:

- actuarial studies[37][38][39][40][41][42][43]

- assay analysis [44][45]

- survival analysis[46][47][48]

- ecology [11]

- analysis of alcohol consumption in British teenagers [49]

- medical applications [50]

- meteorology and climatology [50][51]

- fisheries [52]

- Mertens function [53]

- self-organized criticality[54]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Tweedie, M.C.K. (1984). "An index which distinguishes between some important exponential families". In Ghosh, J.K.; Roy, J. Statistics: Applications and New Directions. Proceedings of the Indian Statistical Institute Golden Jubilee International Conference. Calcutta: Indian Statistical Institute. pp. 579–604. MR 786162.

- ↑ Jørgensen, B (1987). "Exponential dispersion models". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B 49 (2): 127–162. JSTOR 2345415.

- ↑ Smith, C.A.B. (1997). "Obituary: Maurice Charles Kenneth Tweedie, 1919–96". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 160 (1): 151–154. doi:10.1111/1467-985X.00052.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Jørgensen, Bent (1997). The theory of dispersion models. Chapman & Hall. ISBN 978-0412997112.

- ↑ Jørgensen, B; Martinez, JR & Tsao, M (1994). "Asymptotic behaviour of the variance function". Scandinavian Journal of Statistics 21: 223–243.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 Kendal, W. S.; Jørgensen, B. (2011). "Tweedie convergence: A mathematical basis for Taylor's power law, 1/f noise, and multifractality". Physical Review E 84 (6). Bibcode:2011PhRvE..84f6120K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.84.066120.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Taylor LR (1961) Aggregation, variance and the mean. Nature 189, 732–735

- ↑ Hanski I (1980) Spatial patterns and movements in coprophagous beetles. Oikos 34, 293–310

- ↑ Anderson RD, Crawley GM & Hassell M (1982) Variability in the abundance of animal and plant species. Nature 296, 245–248

- ↑ Fronczak A & Fronczak P (2010) Origins of Taylor’s power law for fluctuation scaling in complex systems. Phys Rev E 81, 066112

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Kendal WS (2002) Spatial aggregation of the Colorado potato beetle described by an exponential dispersion model. Ecological Modelling 151, 261–269

- ↑ Kendal WS (2004) Taylor’s ecological power law as a consequence of scale invariant exponential dispersion models. Ecol Complex 1, 193–209

- ↑ Dutta P & Horn PM (1981) Low frequency fluctuations in solids: 1/f noise. Rev Mod Phys 53,497–516

- ↑ Leland WE, Taqqu MS, Willinger W & Wilson DV (1994) On the self-similar nature of ethernet traffic. IEE/ACM Trans Networking 2, 1–15

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Tsybakov B & Georganas ND (1997) On self-similar traffic in ATM queues: definitions, overflow probability bound, and cell delay distribution. IEEE/ACM Trans Networking 5, 397–409

- ↑ Kendal WS (2007) Scale invariant correlations between genes and SNPs on Human chromosome 1 reveal potential evolutionary mechanisms. J Theor Biol 245, 329–340

- ↑ McQuarrie DA (1976) Statistical mechanics [Harper & Row]

- ↑ Kendal WS (2014) Multifractality attributed to dual central limit-lie convergence effects. Physica A 401, 22–33

- ↑ Jørgensen B, Kokonendji CC (2011) Dispersion models for geometric sums. Braz J Probab Stat 25, 263–293

- ↑ Bassingthwaighte JB (1989) Fractal nature of regional myocardial blood flow heterogeneity. Circ Res 65, 578–590

- ↑ Kendal WS (2001) A stochastic model for the self-similar heterogeneity of regional organ blood flow. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98, 837–841

- ↑ Honig CR, Feldstein ML, Frierson JL. 1977. Capillary lengths, anastomoses, and estimated capillary transit times in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circul Physiol 233: H122--H129.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Fidler, IJ; Kripke, M (1977). "Metastasis results from preexisting variant cells within a malignant tumor". Science 197: 893–895. Bibcode:1977Sci...197..893F. doi:10.1126/science.887927.

- ↑ Kendal WS & Frost P (1987) Experimental metastasis: a novel application of the variance-to-mean power function. J Natl Cancer Inst 79, 1113–1115

- ↑ Kendal WS. 1999. Clustering of murine lung metastases reflects fractal nonuniformity in regional lung blood flow. Invasion Metastasis 18: 285–296.

- ↑ Kendal WS, Lagerwaard, FJ & Agboola O. 2000. Characterization of the frequency distribution for human hematogenous metastases: evidence for clustering and a power variance function. Clin Exp Metastasis 18: 219–229.

- ↑ Weiss L, Bronk J, Pickren JW & Lane WW. 1981. Metastatic patterns and targe organ arterial blood flow. Invasion Metastasis 1: 126–135.

- ↑ Chambers AF, Groom AC & MacDonald IC. 2002. Dissemination and growth of cancer cells in metastatic sites. Nature Rev Cancer 2: 563–572.

- ↑ Kendal WS. 2002. A frequency distribution for the number of hematogenous organ metastases. Invasion Metastasis 1: 126–135.

- ↑ Kendal WS (2003) An exponential dispersion model for the distribution of human single nucleotide polymorphisms" Mol Biol Evol 20 579–590

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Kendal, WS (2004). "A scale invariant clustering of genes on human chromosome 7". BMC Evol Biol 4: 3. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-4-3. PMC 373443. PMID 15040817.

- ↑ The international SNP map working group. 2001. A map of human genome variation containing 1.42 million single nucleotide polymorphisms" Nature 409: 928–933.

- ↑ Hudson RR. 1991. Gene genealogies and the coalescent process. Oxford surveys in evolutionary biology 7: 1–44.

- ↑ Tavare S, Balding DJ, Griffiths RC & Donnelly P. 1997. Inferring coalescent times from DNA sequence data" Genetics 145: 505–518.

- ↑ Schoenfeld, J (1976). "Sharper bounds for the Chebyshev functions θ(x) and ψ(x). II". Math Computation 30 (134): 337–360. doi:10.1090/s0025-5718-1976-0457374-x.

- ↑ Kendal, WS (2013). "Fluctuation scaling and 1/f noise: shared origins from the Tweedie family of statistical distributions". J Basic Appl Phys 2: 40–49.

- ↑ Haberman, S. and Renshaw, A. E. 1996. Generalized linear models and actuarial science. The Statistician, 45: 407–436.

- ↑ Renshaw, A. E. 1994. Modelling the claims process in the presence of covariates. ASTIN Bulletin 24: 265–286.

- ↑ Jørgensen, B. and Paes de Souza, M. C. 1994. Fitting Tweedie's compound Poisson model to insurance claims data. Scand. Actuar. J. 1: 69–93.

- ↑ Haberman, S., and Renshaw, A. E. 1998. Actuarial applications of generalized linear models. In Statistics in Finance, D. J. Hand and S. D. Jacka (eds), Arnold, London.

- ↑ Mildenhall, S. J. 1999. A systematic relationship between minimum bias and generalized linear models. 1999 Proceedings of the Casualty Actuarial Society 86: 393–487.

- ↑ Murphy, K. P., Brockman, M. J., and Lee, P. K. W. (2000). Using generalized linear models to build dynamic pricing systems. Casualty Actuarial Forum, Winter 2000.

- ↑ Smyth, G.K.; Jørgensen, B. (2002). "Fitting Tweedie's compound Poisson model to insurance claims data: dispersion modelling". ASTIN Bulletin 32: 143–157. doi:10.2143/ast.32.1.1020.

- ↑ Davidian, M. 1990. Estimation of variance functions in assays with possible unequal replication and nonnormal data. Biometrika 77: 43–54.

- ↑ Davidian, M., Carroll, R. J. and Smith, W. 1988. Variance functions and the minimum detectable concentration in assays. Biometrika 75: 549–556.

- ↑ Aalen, O. O. 1992. Modelling heterogeneity in survival analysis by the compound Poisson distribution. Ann. Appl. Probab. 2: 951–972.

- ↑ Hougaard, P. , Harvald, B. and Holm, N. V. 1992. Measuring the similarities between the lifetimes of adult Danish twins born between 1881–1930. Journal of the American Statistical Association 87: 17–24.

- ↑ Hougaard, P. 1986. Survival models for heterogeneous populations derived from stable distributions. Biometrika, 73: 387–396.

- ↑ Gilchrist, R. and Drinkwater, D. 1999. Fitting Tweedie models to data with probability of zero responses. Proceedings of the 14th International Workshop on Statistical Modelling, Graz, pp. 207–214.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Smyth, G. K. 1996. Regression analysis of quantity data with exact zeros. Proceedings of the Second Australia--Japan Workshop on Stochastic Models in Engineering, Technology and Management. Technology Management Centre, University of Queensland, 572– 580.

- ↑ Hasan, M.M.; Dunn, P.K. (2010) "Two Tweedie distributions that are near-optimal for modelling monthly rainfall in Australia", International Journal of Climatology, doi:10.1002/joc.2162

- ↑ Candy, S. G. 2004. Modelling catch and effort data using generalized linear models, the Tweedie distribution, random vessel effects and random stratum-by-year effects. CCAMLR Science. 11: 59–80.

- ↑ Kendal WS & Jørgensen B (2011) Taylor's power law and fluctuation scaling explained by a central-limit-like convergence. Phys. Rev. E 83,066115

- ↑ Kendal, WS (2015). "Self-organized criticality attributed to a central limit-like convergence effect". Physica A 421: 141–150.

Further reading

- Kaas, R. (2005). "Compound Poisson distribution and GLM’s – Tweedie’s distribution". In Proceedings of the Contact Forum "3rd Actuarial and Financial Mathematics Day", pages 3–12. Brussels: Royal Flemish Academy of Belgium for Science and the Arts.

- Ohlsson, E and Johansson, B. (2003) Exact Credibility and Tweedie Models, University of Stockholm, Research report, October 2003.

- Tweedie, M.C.K. (1956). "Some statistical properties of inverse Gaussian distributions". Virginia J. Sci. (N.S.) 7, 160—165.

External links

- Tweedie distributions. http://www.statsci.org/s/tweedie.html

- Tweedie generalized linear model family. http://www.statsci.org/s/tweedief.html

- Examples of use of the model. http://www.sci.usq.edu.au/staff/dunn/Datasets/tech-glms.html#Tweedie

- tweeDEseq: R package for RNA-seq data analysis using the Poisson-Tweedie family of distributions. http://bioconductor.org/packages/2.9/bioc/html/tweeDEseq.html

![\text{var}\,(Y) = a[\text{E}\,(Y)]^p ,](../I/m/a31cf95c80eebf236bc2abb8f74004cd.png)

![P_{\lambda,\theta}(Z\in A)=\int_{A} \exp[\theta \cdot z-\lambda\kappa(\theta)]\cdot \nu_\lambda\, (dz),](../I/m/ffc9ab0dd150a757d45968709636e76a.png)

![V(\mu)=\tau^\prime[\tau^{-1}(\mu)].](../I/m/ac781a5f0d14eea6bad3052d29d530f3.png)

![K^*(s)=\log[\text{E}(e^{sZ})]=\lambda[\kappa(\theta+s)-\kappa(\theta)],](../I/m/390ba2582fa64c1fd6a570ca8894ddd6.png)

![K(s)=\log[\text{E}(e^{sY})]=\lambda[\kappa(\theta+s/\lambda)-\kappa(\theta)],](../I/m/283243f2e77036d315e9ce849454ffda.png)

![K^*_p(s;\theta,\lambda) = \begin{cases} \lambda\kappa_p(\theta)[(1+s/\theta)^\alpha-1]

& \quad p \ne 1,2, \\ -\lambda \log(1+s/\theta) & \quad p = 2, \\ \lambda e^\theta (e^s -1) & \quad p = 1, \end{cases}](../I/m/634df46b968c83268aea6c60cb0459b6.png)

![K_p(s;\theta,\lambda) = \begin{cases} \lambda\kappa_p(\theta)\left \{ [1+s/(\theta \lambda)]^\alpha-1 \right \}

& \quad p \ne 1,2, \\ -\lambda \log[1+s/(\theta \lambda)] & \quad p = 2, \\ \lambda e^\theta (e^{s/\lambda} -1) & \quad p = 1. \end{cases}](../I/m/f3ff88ad568e4fbe3891e0b790adba94.png)

![\text{var}[Y^{(m)}]=\hat{\sigma}^2 m^{-d}](../I/m/8231dd9bfbedb3fb4e2888b0cbd9c315.png)

![\text{var}[Z_i^{(m)}]=m^2 \text{var}[Y^{(m)}]=(\hat{\sigma}^2 /\hat{\mu}^{2-d})\text{E}[Z_i^{(m)}]^{2-d}](../I/m/28b9503a49961202ad7273b4c1980e76.png)

![G(s)= \exp \left [\lambda \frac {\alpha-1}{\alpha} \left( \frac{\theta} {\alpha-1} \right)^\alpha \left\{ \left(1- \frac{1} {\theta}+ \frac {s} {\theta}\right)^\alpha-1 \right\}\right]](../I/m/8e2182d29f04c8ab0b4dd5cc14397a40.png)

![\bar{\eta}(E) = \frac{1}{2\pi}\left [E\sqrt{2N-E^2}+2N \arcsin \left( \frac{E}{\sqrt{2N}} \right )+ \pi N \right ].](../I/m/a54c81f1bc8734da99006c33be8b2742.png)