Tumbao

In music of Afro-Cuban origin, tumbao is the basic rhythm played on the bass. In North America, the basic conga drum pattern used in popular music is also called tumbao. In the contemporary form of Cuban popular dance music known as timba, piano guajeos are known as tumbaos.[1]

Bass pattern

Clave-neutral

The tresillo pattern is the rhythmic basis of the ostinato bass tumbao in Cuban son-based musics, such as son montuno, mambo, salsa, and Latin jazz.[2][3]

Often the last note of the measure is held over the downbeat of the next measure. In this way, only the two offbeats of tresillo are sounded. The first offbeat is known as bombo, and the second offbeat (last note) is sometimes referred to as ponche.[4] The following example is written in cut-time (2/2).

Clave-aligned

Arsenio Rodríguez's group introduced bass tumbaos that have a specific alignment with clave. The 2-3 bass line of "Dame un cachito pa' huele" (1946) coincides with three of the clave's five strokes.[5] Listen to a midi version of the bass line for "Dame un cachito pa' huele."

David García Identifies the accents of "and-of-two" (in cut-time) on the three-side, and the "and-of-four" (in cut-time) on the two-side of the clave, as crucial contributions of Rodríguez's music.[6] The two offbeats are present in the following 2-3 bass line from Rodríguez's "Mi chinita me botó" (1944).[7]

The two offbeats are especially important because they coincide with the two syncopated steps in the son's basic footwork. The conjunto's collective and consistent accentuation of these two important offbeats gave the son montuno texture its unique groove and, hence, played a significant part in the dancer's feeling the music and dancing to it, as Bebo Valdés noted "in contratiempo" ['offbeat timing']—García (2006: 43).[8]

Moore points out that Rodríguez's conjunto introduced the two-celled bass tumbaos, that moved beyond the simpler, single-cell tresillo structure.[9] This type of bass line has a specific alignment to clave, and contributes melodically to the composition. Rodríguez's brother Raúl Travieso recounted, Rodríguez insisted that his bass players make the bass "sing."[10] Moore states: "This idea of a bass tumbao with a melodic identity unique to a specific arrangement was critical not only to timba, but also to Motown, rock, funk, and other important genres."[11] In other words, Rodríguez is a creator of the bass riff.

Timba

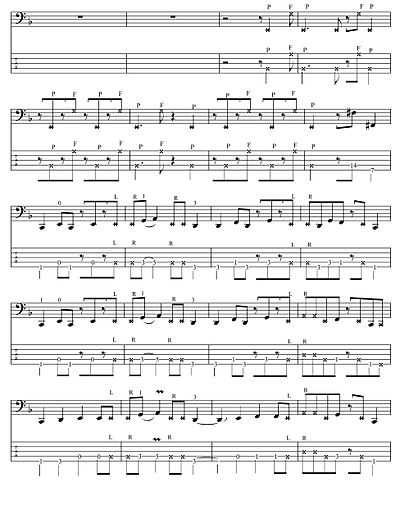

Timba tumbaos incorporate techniques from funk, such as slapping, and pulling the strings in a percussive way. The following excerpt demonstrates several characteristics of timba bass. This is Alain Pérez's tumbao from a performance of Issac Delgado piece "La vida sin esperanza." Pérez's playful interpretation of the tumbao is what timba authority Kevin Moore refers to as “controlled improvisation;" the pattern continuously varies within a set framework.[12] Watch: Alain Pérez play funky timba bass.

Conga drum pattern

Clave-neutral

The basic son montuno tumbao pattern is played on the conga drum. The conga was first used in bands during the late 1930s, and became a staple of mambo bands of the 1940s. The primary strokes are sounded with open tones, on the last offbeats (2&, 2a) of a two-beat cycle. The fundamental accent—2& is referred to by some musicians as ponche.[13]

1 e & a 2 e & a Count H T S T H T O O Conga L L R L L L R R Hand Used Key: L: Left hand R: Right hand H: Heel of hand T: Tip of hand S: Slap O: Open Tone

Clave-aligned

The basic tumbao sounds slaps (triangle noteheads) and open tones (regular noteheads) on the "and" offbeats.[14] There are many variations on the basic tumbao. For example, a very common variant sounds a single open tone with the third stroke of clave (ponche), and two tones preceding the three-side of clave. The specific alignment between clave and this tumbao is critical.

Another common variant uses two drums and sounds bombo (1a) on the tumba (3-side of the clave).[15] For example:

1 . & . 2 . & . 3 . & . 4 . & . Count

X X X X X Son Clave

X X X X X Rumba Clave

H T S T O O H T S T H T O O Conga

O O Tumba

L L R R R L R R L L R L L L R R Hand Used

or

1 . & . 2 . & . 3 . & . 4 . & . Count

X X X X X Son Clave

X X X X X Rumba Clave

H T S H T O O H T S H T O O Conga

O 0 Tumba

L L R R L L R R L L R R L L R R Hand Used

Songo era

Beginning in the late 1960s, band conga players began incorporating elements from folkloric rhythms, especially rumba. Changuito and Raúl "el Yulo" Cárdenas of Los Van Van pioneered this approach of the songo era.

This relationship between the drums is derived from the style known as rumba. The feeling of the high drum part is like the quinto in rumba, constantly punctuating, coloring, and accenting, but not soloing until the appropriate moment (Santos 1985).[16]

In several songo arrangements, the tumbadora ('conga') part sounds the typical tumbao on the low-pitched drum, while replicating the quinto (lead drum) of guaguancó on the high-pitched drum. The quinto-like phrases can continually change, but they are based upon a specific counter-clave motif.[17] [See: "Songo Patterns on Congas" (Changuito).

Timba era

Tomás Cruz developed several adaptions of folkloric rhythms when working in Paulito FG's timba band of the 1990s. Cruz's creations offered clever counterpoints to the bass and chorus. Many of his tumbaos span two or even four claves in duration, something very rarely done previously.[18] He also made more use of muted tones in his tumbaos, all the while advancing the development of . The example on the right is one of Cruz's inventos ('musical inventions'), a band adaptation of the Congolese-based Afro-Cuban folkloric rhythm makuta. He played the pattern on three congas on the Paulito song "Llamada anónima." Listen: "Llamada Anónima" by Paulito F.G.

Timba keyboard guajeos

The Cuban jazz pianist Gonzalo Rubalcaba developed a technique of pattern and harmonic displacement in the 1980s, which was adopted into timba tumbaos (timba piano guajeos) in the 1990s. The following tumbao for Issac Delgado's "La temática" (1997) demonstrates some of the innovations of timba piano. A series of repeated octaves invoke a characteristic metric ambiguity. The following timba examples are written in cut-time.

Many timba bands use two keyboards. The following example shows two simultaneous tumbao parts for Issac Delgado's "Por qué paró" (1995), as played by Melón Lewis (1st keyboard), and Pepe Rivero (2nd keyboard).[19]

References

- ↑ Moore, Kevin (2010). Beyond Salsa Piano v.1 p. 32. Santa Cruz, CA: Moore Music/Timba.com. ISBN‐10: 1439265844

- ↑ Peñalosa, David (2009: 40). The Clave Matrix; Afro-Cuban Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins. Redway, CA: Bembe Inc. ISBN 1-886502-80-3.

- ↑ "Alza los pies Congo," Septeto Habanero. (CD: 1925).

- ↑ [The] clave pattern has two opposing rhythm cells: the first cell consists of three strokes, or the rhythm cell, which is called tresillo (Spanish tres = three). This rhythmically syncopated part of the clave is called the three-side or the strong part of the clave. The second cell has two strokes and is called the two-side or the weak part of the clave. . . The different accent types in the melodic line typically encounter with the clave strokes, which have some special name. Some of the clave strokes are accented both in more traditional tambores batá -music and in more modern salsa styles. Because of the popularity of these strokes, some special terms have been used to identify them. The second stroke of the strong part of the clave is called bombo. It is the most often accented clave stroke in my research material. Accenting it clearly identifies the three-side of the clave (Peñalosa 2009, The Clave Matrix 93-94). The second common clave stroke accented among these improvisations is the third stroke of the strong part of the clave. This stroke is called ponche. In Cuban popular genres, this stroke is often accented in unison breaks that transition between the song sections (Peñalosa 2009, 95; Mauleón 1993, 169). The third typical way to accent the clave strokes is to play a rhythm cell, which includes both bombo and ponche accents. This rhythm cell is called [the] conga pattern (Ortiz, Fernando 1965 [1950], La Africania De La Musica Folklorica De Cuba 277; Mauleón 1993, 169-170). Iivari, Ville (2011: 1, 5). The Relation Between clave Pattern and Violin Improvisation in Santería’s Religious Feasts. Department of Musicology, University of Turku, Finland. Web. http://www.siba.fi/fi/web/embodimentofauthority/proceedings;jsessionid=07038526F10A06DE7ED190AD5B1744D7

- ↑ Moore, Kevin (2007: web). Arsenio Rodriguez 1946 "Dame un cachito pa' huele." The Roots of Timba part 1. Web. Timba.com.http://www.timba.com/encyclopedia_pages/1946-dame-un-cachito-pa-huele

- ↑ García, David (2006: 43). Arsenio Rodríguez and the transnational flows of latin popular music. Philadelphia : Temple University Press.

- ↑ García 2006 p. 45.

- ↑ García 2006 p. 43.

- ↑ Moore, Kevin 2007. "1945 - No hay yaya sin Guayacán." The Roots of Timba part 1. Web. Timba.com. http://www.timba.com/encyclopedia_pages/1945-no-hay-yaya-sin-guayac-n

- ↑ Raúl Travieso quoted by David García 2006. Arsenio Rodriguez and The Transnational Flows of Latin Popular Music p. 43.

- ↑ Moore 2007. "1945 - No hay yaya sin Guayacán." Timba.com.

- ↑ Moore, Kevin (2012: 80). Beyond Salsa Bass; The Cuban Timba Revolution v. 6, Alain Pérez p. 1. Moore Music/Timba.com. ISBN‐10: 1470143909

- ↑ Mauleón, Rebeca (1993: 63). Salsa Guidebook for Piano and Ensemble. Petaluma, California: Sher Music. ISBN 0-9614701-9-4.

- ↑ Sometimes clave is written in two measures of 4/4 and the open tone of the conga drum are referred to as the last beat of the measure (see Mauleón 1993 p. 63)

- ↑ Mauleón (1993: 64).

- ↑ Santos, John (1985). “Songo,” Modern Drummer Magazine. December p. 44.

- ↑ Peñalosa, David (2010) p. 142-144. Redway, CA: Bembe Books. ISBN 1-4537-1313-1

- ↑ Cruz, Tomás, with Kevin Moore (2004: 25) The Tomás Cruz Conga Method v. 3. Pacific, MO: Mel Bay.

- ↑ Moore, Kevin (2010: 8,9). Beyond Salsa Piano; The Cuban Timba Piano Revolution v.7 Iván "Melón" Lewis, prt. 2 Note for Note Transcriptions. Santa Cruz, CA: Moore Music/Timba.com. ISBN‐10: 1450545637