Tsurezuregusa

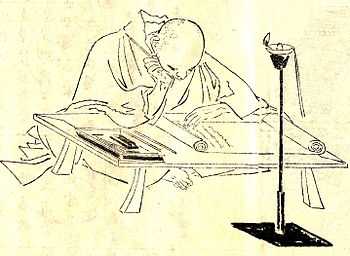

Tsurezuregusa (徒然草, Essays in Idleness, also known as The Harvest of Leisure) is a collection of essays written by the Japanese monk Yoshida Kenkō between 1330 and 1332. The work is widely considered a gem of medieval Japanese literature and one of the three representative works of the zuihitsu genre, along with Makura no Sōshi and the Hōjōki.

Structure and Content

Tsurezuregusa comprises a preface and 243 passages (段, dan), varying in length from a single line to a few pages. Kenkō, being a Buddhist monk, writes about Buddhist truths, and themes such as death and impermanence prevail in the work, although it also contains passages devoted to the beauty of nature as well as some accounts of humorous incidents. The original work was not divided or numbered; the division can be traced to the 17th century.

The work takes its title from its prefatory passage:

つれづれなるまゝに、日暮らし、硯にむかひて、心にうつりゆくよしなし事を、そこはかとなく書きつくれば、あやしうこそものぐるほしけれ。

Tsurezurenaru mama ni, hikurashi, suzuri ni mukaite, kokoro ni utsuriyuku yoshinashigoto wo, sokowakatonaku kakitsukureba, ayashū koso monoguruoshikere.

In Keene's translation:

What a strange, demented feeling it gives me when I realise I have spent whole days before this inkstone, with nothing better to do, jotting down at random whatever nonsensical thoughts that have entered my head.

Here つれづれ (tsurezure) means “having nothing to do.”

For comparison, Sansom's translation:

To while away the idle hours, seated the livelong day before the inkslab, by jotting down without order or purpose whatever trifling thoughts pass through my mind, truly this is a queer and crazy thing to do!

Mystery of the Origin

Despite the distinguished work of Kenko being continually held in high regard among many and considered a classic since the 17th century, the origin to the publication of Kenko’s work is unclear. Many people have speculated different theories to the arrival of his work, however, little is known to the exact manner of how the book itself was compiled and put together. One of the most popular beliefs held among the majority was concluded by Sanjonishi Saneeda (1511-1579), who stated that Kenko himself did not edit the 243 chapters of his work, but rather, simply wrote his thoughts on random scrap pieces of paper which he pasted to the walls of his cottage. It was then hypothesized that Kenko’s friend, Imagawa Ryoshun, who was also a poet and general at that time, was the one who compiled the book together. After finding the notes on Kenko’s wall, he had prudently removed the scraps and combined the pieces together with other essays of Kenko’s which were found in possession by Kenko’s former servant, and carefully arranged the notes into the order it is found in today.

Modern critics today have rejected this account, skeptical of the possibility that any other individual aside from Kenko himself could have put together such an insightful piece of work. However, the oldest surviving texts of Tsurezuregusa have been found in the hands of Ryoshun’s disciple, Shotetsu, making Sanjonishi’s theory to become widely considered by people today.

Theme of Impermanence

Throughout Tsurezuregusa, a consistent theme regarding the impermanence of life is noted in general as a significant principle in Kenko’s work. Tsurezuregusa overall comprises this concept, making it a highly relatable work to many as it touches on the secular side among the overtly Buddhist beliefs mentioned in some chapters of the work.

Kenko relates the impermanence of life to the beauty of nature in an insightful manner. Kenko sees the aesthetics of beauty in a different light: the beauty of nature lies in its impermanence.Within his work, Kenko quotes the poet Ton’a: “It is only after the silk wrapper has frayed at top and bottom, and the mother-of-pearl has fallen from the roller, that a scroll looks beautiful.”

In agreement with this statement, Kenko shows his support for an appreciation for the uncertain nature of things, and proposes the idea of how nothing last forever is a motivation for us to appreciate everything we have. Kenko himself states this in a similar manner in his work:

“If man were never to fade away like the dews of Adashino, never to vanish like the smoke over Toribeyama, but lingered on forever in this world, how things would lose their power to move us! The most precious thing in life is its uncertainty.”

Kenko clearly states his point of view regarding the nature of things in life, and regards the perishability of objects to be moving. In relation to the concept of impermanence, his works links to the fondness of the irregular and incomplete, and the beginnings and ends of things. Kenko states:

“It is typical of the unintelligent man to insist on assembling complete sets of everything. Imperfect sets are better.”

“Branches about to blossom or gardens strewn with faded flowers are worthier of our admiration. In all things, it is the beginnings and ends that are interesting.” Within his work, Kenko shows the relation of impermanence to the balance of things in life. Beginnings and ends relate to the impermanence of things, and it is because of its impermanence that beginnings and ends are interesting and should be valued. Irregularity and incompleteness of collections and works show the potential for growth and improvement, and the impermanence of its state provides a moving framework towards appreciation towards life.

Kenko’s work predominantly reveals these themes, providing his thoughts set out in short essays of work. Although his concept of impermanence is based upon his personal beliefs, these themes provide a basic concept relatable among many, making it an important classical literature resonating throughout Japanese high school curriculum today.

Translations

The definitive English translation is by Donald Keene (1967). In his preface Keene states that, of the six or so earlier translations into English and German, that by G. B. Sansom is the most distinguished. It was published by the Asiatic Society of Japan in 1911 as The Tsuredzure Gusa of Yoshida No Kaneyoshi: Being the Meditations of a Recluse in the 14th Century.

Sources

- Chance, Linda H (1997). Formless in Form: Kenkō, Tsurezuregusa, and the Rhetoric of Japanese Fragmentary Prose. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804730013.

- Keene, Donald, tr. (1998). Essays in Idleness: The Tsurezuregusa of Kenkō. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231112550.

External links

- The full Japanese text of Tsurezuregusa, with translation into modern Japanese

- English excerpts of Tsurezuregusa. Sansom's translation

- Scanned whole book of English translation by William N. Porter (1914)

- Reading of "Tsurezuregusa"

Footnote

- ^ literally, “as the brush moves,” i.e., jotting down whatever comes to one's mind, usually translated “essay.”