Troodon

| Troodon Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, Possible late Maastrichtian record | |

|---|---|

| |

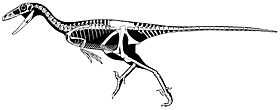

| Restored skeleton of T. inequalis, Perot Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Suborder: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Troodontidae |

| Subfamily: | †Troodontinae Gilmore, 1924 |

| Genus: | †Troodon Leidy, 1856 |

| Type species | |

| †Troodon formosus Leidy, 1856 | |

| Species | |

|

†T. formosus Leidy, 1856 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Polyodontosaurus Gilmore, 1932 | |

Troodon (/ˈtroʊ.ədɒn/ TROH-ə-don; Troödon in older sources) is a genus of relatively small, bird-like dinosaurs known definitively from the Campanian age of the Cretaceous period (about 77 mya), though possible additional species are known from later in the Campanian and also from the early (and probably late[1][2]) Maastrichtian age. It includes at least one species, Troodon formosus, though many fossils, possibly representing several species have been classified in this genus. These species ranged widely, with fossil remains recovered from as far north as Alaska and as far south as Wyoming and even possibly Texas and New Mexico. Discovered in 1855, T. formosus was among the first dinosaurs found in North America.

The genus name is Greek for "wounding tooth", referring to the teeth, which were different from those of most other theropods known at the time of their discovery. The teeth bear prominent, apically oriented serrations. These "wounding" serrations, however, are morphometrically more similar to those of herbivorous reptiles, and suggest a possibly omnivorous diet.[3] A partial Troodon skeleton has been discovered with preserved puncture marks.[4]

Description

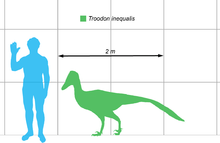

Troodon were small dinosaurs, up to 0.9 metres (3.0 ft) in height, 2.4 metres (7.9 ft) in length,[5] and up to 50 kilograms (110 lb) in mass.[6] The largest specimens are comparable in size to Deinonychus and Unenlagia.[7] They had very long, slender hind limbs, suggesting that these animals were able to run quickly. They had large, retractable sickle-shaped claws on the second toes, which were raised off the ground when running.

Their eyes were very large (perhaps suggesting a partially nocturnal lifestyle), and slightly forward facing, giving Troodon some degree of depth perception.[8]

Brain and inner ear

Troodon had some of the largest known brains of any dinosaur group, relative to their body mass (comparable to modern birds).[9] Troodon's cerebrum-to-brain-volume ratio was 31.5% to 63% of the way from a nonavian reptile proportion to a truly avian one.[10] Troodon had bony cristae supporting their tympanic membranes that were ossified at least in their top and bottom regions. The rest of the cristae were either cartilaginous or too delicate to be preserved. The metotic strut of Troodon was enlarged from side-to-side, similar to Dromaeosaurus and primitive birds like Archaeopteryx and Hesperornis.[10]

History and classification

The name was originally spelled Troödon (with a diaeresis) by Joseph Leidy in 1856, which was officially amended to its current status by Sauvage in 1876. The type specimen of Troodon has caused problems with classification, as the entire genus is based only on a single tooth from the Judith River Formation. Troodon has historically been a highly unstable classification and has been the subject of numerous conflicting synonymies with similar theropod specimens.[11]

The Troodon tooth was originally classified as a "lacertilian" (lizard) by Leidy, but reassigned as a megalosaurid dinosaur by Nopcsa in 1901 (Megalosauridae having historically been a wastebin taxon for most carnivorous dinosaurs). In 1924, Gilmore suggested that the tooth belonged to the herbivorous pachycephalosaur Stegoceras, and that Stegoceras was in fact a junior synonym of Troodon (the similarity of troodontid teeth to those of herbivorous dinosaurs continues to lead many paleontologists to believe that these animals were omnivores). The classification of Troodon as a pachycephalosaur was followed for many years, during which the family Pachycephalosauridae was known as Troodontidae. In 1945, Charles Mortram Sternberg rejected the possibility that Troodon was a pachycephalosaur due to its stronger similarity to the teeth of other carnivorous dinosaurs. With Troodon now classified as a theropod, the family Troodontidae could no longer be used for the dome-headed dinosaurs, so Sternberg named a new family for them, Pachycephalosauridae.[12]

The first specimen currently assigned to Troodon that was not a tooth was named Stenonychosaurus by Sternberg in 1932, based on a foot, fragments of a hand, and some tail vertebrae from the Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta. A remarkable feature of these remains was the enlarged claw on the second toe, which is now recognized as characteristic of early paravians. Sternberg initially classified Stenonychosaurus as a member of the family Coeluridae. Later, in 1951, Sternberg speculated that since Stenonychosaurus had a "very peculiar pes" and Troodon "equally unusual teeth", they may be closely related. Unfortunately, no comparable specimens were available at that time to test the idea.

A more complete skeleton of Stenonychosaurus was described by Dale Russell in 1969 from the Dinosaur Park Formation, which eventually formed the scientific foundation for a famous life-sized sculpture of Stenonychosaurus accompanied by its fictional, humanoid descendant, the "dinosauroid".[13] Stenonychosaurus became a well-known theropod in the 1980s, when the feet and braincase were described in more detail. Along with Saurornithoides, it formed the family Saurornithoididae. Based on differences in tooth structure, and the extremely fragmentary nature of the original Troodon formosus specimens, saurornithoidids were thought to be close relatives while Troodon was considered a dubious possible relative of the family. Phil Currie, reviewing the pertinent specimens in 1987, showed that supposed differences in tooth and jaw structure among troodontids and saurornithoidids were based on age and position of the tooth in the jaw, rather than a difference in species. He reclassified Stenonychosaurus inequalis as well as Polyodontosaurus grandis and Pectinodon bakkeri as junior synonyms of Troodon formosus. Currie also made Saurornithoididae a junior synonym of Troodontidae.[14] In 1988, Gregory S. Paul went farther and included Saurornithoides mongoliensis in the genus Troodon as T. mongoliensis,[15] but this reclassification, along with many other unilateral synonymizations of well known genera, was not adopted by other researchers. Currie's classification of all North American troodontid material in the single species Troodon formosus became widely adopted by other paleontologists, and all of the specimens once called Stenonychosaurus were referred to as Troodon in the scientific literature through the early 21st century.

However, the concept that all Late Cretaceous North American troodontids belong to one species began to be questioned soon after Currie's 1987 paper was published, including by Currie himself. Currie and colleagues (1990) noted that, while they believed the Judith River troodontids were all T. formosus, troodontid fossils from other formations, such as the Hell Creek Formation and Lance Formation, might belong to different species. In 1991, George Olshevsky assigned the Lance formation fossils, which had first been named Pectinodon bakkeri but later synonymized with Troodon formosus to the species Troodon bakkeri, and several other researchers (including Currie) have reverted to keeping the Dinosaur Park Formation fossils separate as Troodon inequalis (formerly Stenonychosaurus inequalis).[16]

In 2011, Zanno and colleagues reviewed the convoluted history of troodontid classification in Late Cretaceous North America. They followed Longrich (2008) in treating Pectinodon bakkeri as a valid genus, and noted that it is likely the numerous Late Cretaceous specimens currently assigned to Troodon formosus almost certainly represent numerous new species, but that a more thorough review of the specimens is required. Because the holotype of T. formosus is a single tooth, this may render Troodon a nomen dubium.[11]

Taxonomy

Troodon is considered to be one of the most derived members of its family. Along with Zanabazar, Saurornithoides and Talos it forms a clade of specialized troodontids.[11]

Below is a cladogram of Troodontidae by Zanno et al. in 2011.[11]

| Troodontidae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Distribution

The type specimen of Troodon formosus was found in the Judith River Formation of Montana. The rocks of the Judith River Formation are equivalent in age with the Oldman Formation of Alberta,[17] which has been dated to between 77.5 and 76.5 million years ago.[18]

In the past, remains have been attributed to the same genus as the Judith River Troodon from a wide variety of other geological formations. It is now recognized as unlikely that all of these fossils, which come from localities hundreds or thousands of miles apart, separated by millions of years of time, represent a single species or genus of troodontid dinosaurs. Further study and more fossils are needed to determine how many species of Troodon existed. It is questionable that, after further study, any additional species can be referred to Troodon, in which case the genus would be considered a nomen dubium.[11]

Additional specimens currently referred to Troodon come from the upper Two Medicine Formation of Montana, the Dinosaur Park Formation and Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta, the Prince Creek Formation of Alaska, the Hell Creek Formation, Lance Formation, and the Scollard Formation. There is some evidence that Troodon favored cooler climates, as its species seem to have been particularly abundant in northern and even arctic areas and during cooler intervals, such as the early Maastrichtian.[19] Possible Troodon teeth have been found in the lower Javelina Formation of Texas and the Naashoibito Member of the Kirtland Formation in New Mexico.[20][21]

Paleobiology

Troodon are thought to have been predators, a view supported by its sickle claw on the foot and apparently good binocular vision.

Troodon teeth, however, are different from most other theropods. One comparative study of the feeding apparatus suggests that Troodon could have been an omnivore.[3] The jaws met in a broad, U-shaped symphysis similar to that of an iguana, a lizard species adapted to a plant-eating lifestyle. Additionally, the teeth of Troodon bore large serrations each of which is called a denticle. There are pits at the intersections of the denticles, and the points of the denticles point towards the tip, or apex, of each tooth. The teeth show wear facets on their sides. Holtz (1998) also noted that characteristics used to support a predatory habit for Troodon - the grasping hands, large brain and stereoscopic vision, are all characteristics shared with the herbivorous/omnivorous primates and omnivorous Procyon (raccoon).

One study was based on the many Troodon teeth that have been collected from Late Cretaceous deposits from northern Alaska. These teeth are much larger than those collected from more southern sites, providing evidence that northern Alaskan populations of Troodon grew to larger average body size. The study suggests that the Alaskan Troodons may have had access to large animals as prey because there were no tyrannosaurids in their habitat to provide competition for those resources. This study also provides an analysis of the proportions and wear patterns of a large sample of Troodon teeth. It proposes that the wear patterns of all Troodon teeth suggest a diet of soft foods - inconsistent with bone chewing, invertebrate exoskeletons, or tough plant items. This study hypothesizes a diet primarily consisting of meat.[22]

Age determination studies performed on the fossilized remains of Troodon using growth ring counts suggest that this dinosaur reached its adult size probably in 3–5 years.[23]

Pathology

A parietal bone catalogued as TMP 79.8.1 referred to Troodon formosus bears a "pathological aperture". In 1985 Phil Currie hypothesized that this aperture was caused by a cyst, but in 1999 Tanke and Rothschild interpreted it as a possible bite wound. One hatchling specimen may have suffered from a congenital defect resulting in the front part of its jaw being twisted.[24] In a 2001 study conducted by Bruce Rothschild and other paleontologists, 21 foot bones referred to Troodon were examined for signs of stress fracture, but none were found.[25]

Reproduction

Dinosaur eggs and nests were discovered by John R. Horner in 1983 in the Two Medicine Formation of Montana. Varriccho et al. (2002) have described eight of these nests found to date. These are all in the collection of the Museum of the Rockies and their accession numbers are MOR 246, 299, 393, 675, 676, 750, 963, 1139. Horner (1984) found isolated bones and partial skeletons of the hypsilophodont Orodromeus very near the nests in the same horizon and described the eggs as those of Orodromeus.[26] Horner and Weishampel (1996) reexamined the embryos preserved in the eggs and determined that they were those of Troodon, not Orodromeus.[27] Varricchio et al. (1997) made this determination with even more certainty when they described a partial skeleton of an adult Troodon (MOR 748) in contact with a clutch of at least five eggs (MOR 750), probably in a brooding position.[28]

Varricchio et al. (1997) described the exact structure of Troodon nests. They were built from sediments, they were dish shaped, about 100 cm in internal diameter, and with a pronounced raised rim encircling the eggs. The more complete nests had between 16 (minimum number in MOR 246) and 24 (MOR 963) eggs. The eggs are shaped like elongated teardrops, with the more tapered ends pointed downwards and imbedded about halfway in the sediment. The eggs are pitched at an angle so that, on average, the upper half is closer to the center of the nest. There is no evidence that plant matter was present in the nest.

Varricchio et al.(1997) were able to extract enough evidence from the nests to infer several characteristics of Troodon reproductive biology. The results are that Troodon appears to have a type of reproduction that is intermediate between crocodiles and birds, as phylogeny would predict. The eggs are statistically grouped in pairs, which suggests that the animal had two functional oviducts, like crocodiles, rather than one, as in birds. Crocodiles lay many eggs that are small proportional to adult body size. Birds lay fewer, larger, eggs. Troodon was intermediate, laying an egg of about 0.5 kg for a 50 kg adult. This is 10 times larger than reptiles of the same mass, but two Troodon eggs are roughly equivalent to the 1.1 kg egg predicted for a 50 kg bird.

Varricchio et al. also found evidence for iterative laying, where the adult might lay a pair of eggs every one or two days, and then ensured simultaneous hatching by delaying brooding until all eggs were laid. MOR 363 was found with 22 empty (hatched) eggs, and the embryos found in the eggs of MOR 246 were in very similar states of development, implying that all of the young hatched simultaneously. The embryos had an advanced degree of skeletal development, implying that they were precocial or even superprecocial. The authors estimated 45 to 65 total days of adult nest attendance for laying, brooding, and hatching. The authors found no evidence that the young remained in the nest after hatching and suggested that they dispersed like hatchling crocodiles or megapode birds instead.[29]

Varricchio et al. (2008) examined the bone histology of Troodon specimen MOR 748 and found that it lacked the bone resorption patterns that would indicate it was an egg-laying female. They also measured the ratio of the total volume of eggs in Troodon clutches to the body mass of the adult. They graphed correlations between this ratio and the type of parenting strategies used by extant birds and crocodiles and found that the ratio in Troodon was consistent with that in birds where only the adult male broods the eggs. From this they concluded that Troodon females likely did not brood eggs, that the males did, and this may be a character shared between maniraptoran dinosaurs and basal birds.[30]

The "Dinosauroid"

In 1982, Dale A. Russell, then curator of vertebrate fossils at the National Museum of Canada in Ottawa, conjectured a possible evolutionary path for Troodon, if it had not perished in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event 65 million years ago, suggesting that it could have evolved into intelligent beings similar in body plan to humans. Over geologic time, Russell noted that there had been a steady increase in the encephalization quotient or EQ (the relative brain weight when compared to other species with the same body weight) among the dinosaurs. Russell had discovered the first Troodontid skull, and noted that, while its EQ was low compared to humans, it was six times higher than that of other dinosaurs. Russell suggested that if the trend in Troodon evolution had continued to the present, its brain case could by now measure 1,100 cm3, comparable to that of a human.[13]

Troodontids had semi-manipulative fingers, able to grasp and hold objects to a certain degree, and binocular vision.[13] Russell proposed that his "Dinosauroid", like members of the troodontid family, would have had large eyes and three fingers on each hand, one of which would have been partially opposed. Russell also speculated that the "Dinosauroid" would have had a toothless beak. As with most modern reptiles (and birds), he conceived of its genitalia as internal. Russell speculated that it would have required a navel, as a placenta aids the development of a large brain case. However, it would not have possessed mammary glands, and would have fed its young, as some birds do, on regurgitated food. He speculated that its language would have sounded somewhat like bird song.[13][31]

However, Russell's thought experiment has been met with criticism from other paleontologists since the 1980s, many of whom point out that his Dinosauroid is overly anthropomorphic. Gregory S. Paul (1988) and Thomas R. Holtz, Jr., consider it "suspiciously human" and Darren Naish has argued that a large-brained, highly intelligent troodontid would retain a more standard theropod body plan, with a horizontal posture and long tail, and would probably manipulate objects with the snout and feet in the manner of a bird, rather than with human-like "hands".[31]

References

- ↑ Dinosaur distribution (Late Cretaceous;North America;Yukon Territory, Canada). In: Weishampel et al. Page 578

- ↑ 3.12 Wyoming, United States; 9. Ferris Formation. In: Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 585

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Holtz, Thomas R., Brinkman, Daniel L., Chandler, Chistine L. (1998) Denticle Morphometrics and a Possibly Omnivorous Feeding Habit for the Theropod Dinosaur Troodon. Gaia number 15. December 1998. pp. 159-166.

- ↑ Jacobsen, A.R. 2001. Tooth-marked small theropod bone: An extremely rare trace. p. 58-63. In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Ed.s Tanke, D. H., Carpenter, K., Skrepnick, M. W. Indiana University Press.

- ↑ Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2008) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages Supplementary Information

- ↑ Paul, G.S. (1988). Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 396. ISBN 0-671-61946-2.

- ↑ Turner, Alan H.; Mark A. Norell; Diego Pol; Julia A. Clarke; Gregory M. Erickson (2007). "A Basal Dromaeosaurid, And Size Evolution, Preceding Avian Flight". Science Magazine 317 (5843): 1378–81. doi:10.1126/science.1144066. PMID 17823350. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- ↑ Currie, P. J. (1987). "Bird-like characteristics of the jaws and teeth of troodontid theropods (Dinosauria, Saurischia)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 7: 72–81. doi:10.1080/02724634.1987.10011638.

- ↑ Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. pp. 112–113. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Larsson, H.C.E. 2001. Endocranial anatomy of Carcharodontosaurus saharicus (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) and its implications for theropod brain evolution. pp. 19-33. In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Ed.s Tanke, D. H., Carpenter, K., Skrepnick, M. W. Indiana University Press.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Lindsay E. Zanno, David J. Varricchio, Patrick M. O'Connor, Alan L. Titus and Michael J. Knell (2011). "A new troodontid theropod, Talos sampsoni gen. et sp. nov., from the Upper Cretaceous Western Interior Basin of North America". PLoS ONE 6 (9): e24487. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024487. PMC 3176273. PMID 21949721.

- ↑ Sternberg, C. (1945). "Pachycephalosauridae proposed for domeheaded dinosaurs, Stegoceras lambei n. sp., described". Journal of Paleontology 19: 534–538.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Russell, D. A.; Séguin, R. (1982). "Reconstruction of the small Cretaceous theropod Stenonychosaurus inequalis and a hypothetical dinosauroid". Syllogeus 37: 1–43.

- ↑ Currie, P. (1987). "Theropods of the Judith River Formation". Occasional Paper of the Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology 3: 52–60.

- ↑ Paul, G.S. (1988). Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 398–399. ISBN 0-671-61946-2.

- ↑ Currie, P. (2005). "Theropods, including birds." in Currie and Koppelhus (eds). Dinosaur Provincial Park, a spectacular ecosystem revealed, Part Two, Flora and Fauna from the park. Indiana University Press, Bloomington. Pp 367–397.

- ↑ Eberth, David A. (1997). "Judith River Wedge". In Currie, Philip J. & Padian, Kevin (eds.). Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 199–204. ISBN 0-12-226810-5.

- ↑ Arbour, V. M.; Burns, M. E.; Sissons, R. L. (2009). "A redescription of the ankylosaurid dinosaur Dyoplosaurus acutosquameus Parks, 1924 (Ornithischia: Ankylosauria) and a revision of the genus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29 (4): 1117–1135. doi:10.1671/039.029.0405.

- ↑ Fiorillo, Anthony R.; Gangloff, Roland A. (2000). "Theropod teeth from the Prince Creek Formation (Cretaceous) of Northern Alaska, with speculations on Arctic dinosaur paleoecology". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20 (4): 675–682. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2000)020[0675:TTFTPC]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Langston, Standhardt and Stevens, (1989). "Fossil vertebrate collecting in the Big Bend - History and retrospective." in Vertebrate Paleontology, Biostratigraphy and Depositional Environments, Latest Cretaceous and Tertiary, Big Bend Area, Texas. Guidebook Field Trip Numbers 1 a, B, and 49th Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, Austin, Texas, 29 October - 1 November 1989. 11-21.

- ↑ Weil and Williamson, (2000). "Diverse Maastrichtian terrestrial vertebrate fauna of the Naashoibito Member, Kirtland Formation (San Juan Basin, New Mexico) confirms "Lancian" faunal heterogeneity in western North America." Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, 32: A-498.

- ↑ Fiorillo, Anthony R. (2008) "On the Occurrence of Exceptionally Large Teeth of Troodon (Dinosauria: Saurischia) from the Late Cretaceous of Northern Alaska" Palaios volume 23 pp.322-328

- ↑ Varricchio, D. V. (1993). Bone microstructure of the Upper Cretaceous theropod dinosaur Troodon formosus. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 13, 99-104. JSTOR 4523488

- ↑ Molnar, R. E., 2001, Theropod paleopathology: a literature survey: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, p. 337-363.

- ↑ Rothschild, B., Tanke, D. H., and Ford, T. L., 2001, Theropod stress fractures and tendon avulsions as a clue to activity: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, p. 331-336.

- ↑ Horner, John R. (1984) "The nesting behavior of dinosaurs". "Scientific American", 250:130-137.

- ↑ Horner, John R., Weishampel, David B. (1996) "A comparative embryological study of two ornithischian dinosaurs - a correction." "Nature" 383:256-257.

- ↑ Varricchio, David J., Jackson, Frankie, Borkowski, John J., Horner, John R. "Nest and egg clutches of the dinosaur Troodon formosus and the evolution of avian reproductive traits." "Nature" Vol. 385:247-250 16 January 1997.

- ↑ Varricchio, David J.; Horner, John J.; Jackson, Frankie D. (2002). "Embryos and eggs for the Cretaceous theropod dinosaur Troodon formosus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22 (3): 564–576. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0564:EAEFTC]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Varricchio, D. J.; Moore, J. R.; Erickson, G. M.; Norell, M. A.; Jackson, F. D.; Borkowski, J. J. (2008). "Avian Paternal Care Had Dinosaur Origin". Science 322 (5909): 1826–8. doi:10.1126/science.1163245. PMID 19095938.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Naish, D. (2006). Dinosauroids Revisited Darren Naish: Tetrapod Zoology, April 23, 2011.

- Russell, D. A. (1987). "Models and paintings of North American dinosaurs." In: Czerkas, S. J. & Olson, E. C. (eds) Dinosaurs Past and Present, Volume I. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County/University of Washington Press (Seattle and Washington), pp. 114–131.