Tron

| Tron | |

|---|---|

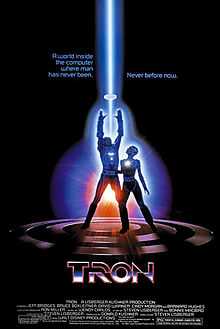

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Steven Lisberger |

| Produced by | Donald Kushner |

| Screenplay by | Steven Lisberger |

| Story by |

Steven Lisberger Bonnie MacBird |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Wendy Carlos |

| Cinematography | Bruce Logan |

| Edited by | Jeff Gourson |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Distribution |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 95 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $17 million |

| Box office | $33 million |

Tron is a 1982 American science fiction film written and directed by Steven Lisberger, based on a story by Lisberger and Bonnie MacBird, and produced by Walt Disney Productions. The film stars Jeff Bridges as a computer programmer who is transported inside the software world of a mainframe computer, where he interacts with various programs in his attempt to get back out. Bruce Boxleitner, David Warner, Cindy Morgan, and Barnard Hughes star in supporting roles.

Development of Tron began in 1976 when Lisberger became fascinated with the early video game Pong. He and producer Donald Kushner set up an animation studio to develop Tron with the intention of making it an animated film. Indeed, to promote the studio itself, Lisberger and his team created a 30-second animation featuring the first appearance of the eponymous character. Eventually, Lisberger decided to include live-action elements with both backlit and computer animation for the actual feature-length film. Various film studios had rejected the storyboards for the film before the Walt Disney Studios agreed to finance and distribute Tron. There, backlit animation was finally combined with the computer animation and live action.

Tron was released on July 9, 1982 in 1,091 theaters in the United States. The film was a moderate success at the box office, but received positive reviews from critics who praised the groundbreaking visuals and acting, but the storyline was criticized at the time for being incoherent. Tron received nominations for Best Costume Design and Best Sound at the 55th Academy Awards, and received the Academy Award for Technical Achievement fourteen years later. Over time, Tron developed into a cult film and eventually spawned a franchise, which consists of multiple video games, comic books and an animated television series.[1] A sequel titled Tron: Legacy directed by Joseph Kosinski was released on December 17, 2010, with Bridges and Boxleitner reprising their roles, and Lisberger acting as producer.

Plot

Kevin Flynn (Jeff Bridges) is a software engineer that runs an arcade bar called Flynn's, and was formerly employed by ENCOM. He wrote several video games, but another ENCOM engineer, Ed Dillinger (David Warner) stole them and passed them off as his own, earning himself a series of promotions. Having left the company, Flynn attempts to obtain evidence of Dillinger's actions by hacking the ENCOM mainframe, but is repeatedly stopped by the Master Control Program (MCP), an artificial intelligence written by Dillinger. When the MCP reveals its plan to take control of outside mainframes including the Pentagon and Kremlin, Dillinger attempts to stop it, only to have the MCP threaten to expose his plagiarism of Flynn's hugely successful games.

Flynn's ex-girlfriend, Lora Baines (Cindy Morgan), and fellow ENCOM engineer, Alan Bradley (Bruce Boxleitner), warn Flynn that Dillinger knows about his hacking attempts and has tightened security. Flynn persuades them to sneak him inside ENCOM, where he forges a higher security clearance for Alan's recently developed security program called "Tron". In response, the MCP uses an experimental laser to digitize Flynn into the ENCOM mainframe, called the Grid, where programs appear in the likeness of the human "users" who created them.

Flynn quickly learns that the MCP and its second-in-command, Sark (Warner), rule over programs and coerce them to renounce their belief in the Users. Those who resist the MCP's tyrannical power over the Grid are forced to play in martial games in which the losers are destroyed. Flynn is forced to fight other programs and meets Tron (Boxleitner) and Ram (Dan Shor) between matches. The three escape into the mainframe during a Light Cycle match. When Ram is mortally wounded and dies, Flynn learns that, as a User, he can manipulate the reality of the digital world.

At an input/output junction, Tron communicates with Alan and receives instructions about how to destroy the MCP. Tron, Flynn and Yori (Morgan) board a "solar sailer simulation" to reach the MCP's core but Sark's command ship destroys the sailer, capturing Flynn and Yori. Sark leaves the command ship and orders its destruction, but Flynn keeps it intact while Sark reaches the MCP's core on a shuttle, carrying captured programs and recruiting them.

While the MCP attempts to consume the captive programs, Tron confronts Sark and critically damages him, prompting the MCP to transfer all of its powers to him. Tron attempts to break through the shield protecting the MCP's core, while Flynn leaps into the MCP, distracting it long enough to reveal a gap in its shield. Tron throws his disc through the gap and destroys the MCP and Sark, ending MCP's tyrannical rule and destroying him.

As programs all over the system begin to communicate with their users, Flynn is sent back to the real world, quickly reconstructed at his terminal. A nearby printer produces the evidence that Dillinger had plagiarized his creations. The next morning, Dillinger enters his office and finds the MCP deactivated and the proof of his theft displayed on the screen and he is sacked. Later, Flynn takes his rightful place as ENCOM's new CEO and is greeted by Alan and Lora on his first day.

Cast

- Jeff Bridges as Kevin Flynn, a former employee at ENCOM who is beamed into the ENCOM mainframe.

- Jeff Bridges also plays Clu (Codified Likeness Utility), a hacking program intended to find evidence of Dillinger's theft in the mainframe.

- Bruce Boxleitner as Alan Bradley, a friend of Kevin Flynn and employee of ENCOM.

- Bruce Boxleitner also plays Tron, a security program developed by Bradley.

- David Warner as Edward "Ed" Dillinger, a senior executive of ENCOM. He was formerly a co-worker of Flynn who stole his work and passed it off as his own, earning him a series of promotions.

- David Warner also plays Sark, a command program and the MCP's second-in-command.

- David Warner likewise provides the uncredited voice of the Master Control Program, a rogue computer program vastly improved by Dillinger.

- Cindy Morgan as Dr. Laura Baines Ph.D., Bradley's co-worker and girlfriend as well as assistant to Dr. Walter Gibbs Ph.D.

- Cindy Morgan also plays Yori, a program created by Dr. Baines and a confidante of Tron.

- Barnard Hughes as Dr. Walter Gibbs, a founder and employee of ENCOM.

- Barnard Hughes also plays Dumont, a "guardian" program protecting input/output junctions.

- Barnard Hughes also plays the original state of the Master Control Program.

- Dan Shor as Ram, an actuarial program for an unnamed insurance company and close friend of Tron and Flynn in the mainframe.

- Dan Shor also plays an unnamed ENCOM employee who asks Bradley if he can have some of his popcorn.

- Peter Jurasik as Crom, an accounting program who fights against Flynn on the Game Grid.

- Tony Stephano as Peter, Dillinger's assistant.

- Tony Stephano also plays Sark's Lieutenant.

Production

Origins

The inspiration for Tron occurred in 1976 when Steven Lisberger, then an animator of drawings with his own studio, looked at a sample reel from a computer firm called MAGI and saw Pong for the first time.[2] He was immediately fascinated by video games and wanted to do a film incorporating them. According to Lisberger, "I realized that there were these techniques that would be very suitable for bringing video games and computer visuals to the screen. And that was the moment that the whole concept flashed across my mind".[3]

Lisberger had already created an early version of the character 'Tron' for a 30 second long animation which was used to promote both Lisberger Studios and a series of various rock radio stations. This backlit cell animation depicted Tron as a character who glowed yellow; the same shade that Lisberger had originally intended for all the heroic characters developed for the feature-length Tron. This was later changed to blue for the finished film (see Pre-production below). The prototype Tron was bearded, and resembled the Cylon Centurions from the original 1978 TV series, Battlestar Galactica. Also, Tron was armed with two "exploding discs", as Lisberger described them on the 2-Disc DVD edition of Tron. Although its possible they may have represented vinyl records, it is interesting to note that in the 2010 film Tron: Legacy, Tron once again appeared using two discs (see Rinzler).

Lisberger elaborates: "Everybody was doing backlit animation in the 70s, you know. It was that disco look. And we thought, what if we had this character that was a neon line, and that was our Tron warrior – Tron for electronic. And what happened was, I saw Pong, and I said, well, that's the arena for him. And at the same time I was interested in the early phases of computer generated animation, which I got into at MIT in Boston, and when I got into that I met a bunch of programmers who were into all that. And they really inspired me, by how much they believed in this new realm."[4]

He was frustrated by the clique-like nature of computers and video games and wanted to create a film that would open this world up to everyone. Lisberger and his business partner Donald Kushner moved to the West Coast in 1977 and set up an animation studio to develop Tron.[3] They borrowed against the anticipated profits of their 90-minute animated television special Animalympics to develop storyboards for Tron with the notion of making an animated film.[2]

The film was conceived as an animated film bracketed with live-action sequences.[3] The rest would involve a combination of computer-generated visuals and back-lit animation. Lisberger planned to finance the movie independently by approaching several computer companies but had little success. However, one company, Information International Inc., was receptive.[3] He met with Richard Taylor, a representative, and they began talking about using live-action photography with back-lit animation in such a way that it could be integrated with computer graphics. At this point, Lisberger already had a script written and the film entirely storyboarded with some computer animation tests completed.[3] He had spent approximately $300,000 developing Tron and had also secured $4–5 million in private backing before reaching a standstill. Lisberger and Kushner took their storyboards and samples of computer-generated films to Warner Bros., MGM, and Columbia Pictures – all of which turned them down.[2]

In 1980, they decided to take the idea to the Walt Disney Studios, which was interested in producing more daring productions at the time.[3] However, Disney executives were uncertain about giving $10–12 million to a first-time producer and director using techniques which, in most cases, had never been attempted. The studio agreed to finance a test reel which involved a flying disc champion throwing a rough prototype of the discs used in the film.[3] It was a chance to mix live-action footage with back-lit animation and computer-generated visuals. It impressed the executives at Disney and they agreed to back the film. The script was subsequently re-written and re-storyboarded with the studio's input.[3] At the time, Disney rarely hired outsiders to make films for them and Kushner found that he and his group were given a less than warm welcome because they "tackled the nerve center – the animation department. They saw us as the germ from outside. We tried to enlist several Disney animators but none came. Disney is a closed group."[5]

Pre-production

Because of the many special effects, Disney decided in 1981 to film Tron completely in 65-mm Super Panavision (except for the computer-generated layers, which were shot in VistaVision and both anamorphic 35mm and Super 35 which were used for some scenes in the "real" world and subsequently "blown up" to 65mm[6]). Three designers were brought in to create the look of the computer world.[3] French comic book artist Jean Giraud (aka Moebius) was the main set and costume designer for the movie. Most of the vehicle designs (including Sark's aircraft carrier, the light cycles, the tank, and the solar sailer) were created by industrial designer Syd Mead, of Blade Runner fame. Peter Lloyd, a high-tech commercial artist, designed the environments.[3] Nevertheless, these jobs often overlapped, leaving Giraud working on the solar sailer and Mead designing terrain, sets and the film's logo. The original 'Program' character design was inspired by Lisberger Studios' logo of a glowing bodybuilder hurling two discs.[3]

To create the computer animation sequences of Tron, Disney turned to the four leading computer graphics firms of the day: Information International, Inc. of Culver City, California, who owned the Super Foonly F-1 (the fastest PDP-10 ever made and the only one of its kind); MAGI of Elmsford, New York; Robert Abel and Associates of California; and Digital Effects of New York City.[3] Bill Kovacs worked on this movie while working for Robert Abel before going on to found Wavefront Technologies. The work was not a collaboration, resulting in very different styles used by the firms.

Tron was one of the first movies to make extensive use of any form of computer animation, and is celebrated as a milestone in the industry though only fifteen to twenty minutes of such animation were used,[7] mostly scenes that show digital "terrain" or patterns or include vehicles such as light-cycles, tanks and ships. Because the technology to combine computer animation and live action did not exist at the time, these sequences were interspersed with the filmed characters. The computer used had only 2MB of memory, and no more than 330MB of storage. This put a limit on detail of background; and at a certain distance, they had a procedure of mixing in black to fade things out, a process called "depth cueing". The movie's Computer Effects Supervisor Richard Taylor told them "When in doubt, black it out!", which became their motto.[8]

Most of the scenes, backgrounds, and visual effects in the film were created using more traditional techniques and a unique process known as "backlit animation".[3] In this process, live-action scenes inside the computer world were filmed in black-and-white on an entirely black set, printed on large format Kodalith high-contrast film, then colored with photographic and rotoscopic techniques to give them a "technological" appearance.[5] With multiple layers of high-contrast, large format positives and negatives, this process required truckloads of sheet film and a workload even greater than that of a conventional cel-animated feature. The Kodalith was specially produced as large sheets by Kodak for the film and came in numbered boxes so that each batch of the film could be used in order of manufacture for a consistent image. However, this was not understood by the filmmakers, and as a result glowing outlines and circuit traces occasionally flicker as the film speed varied between batches. After the reason was discovered, this was no longer a problem as the batches were used in order and "zinger" sounds were used during the flickering parts to represent the computer world malfunctioning as Lisberger described it.[9] Lisberger later had these flickers and sounds digitally corrected for the 2011 restored Blu-ray release as they were not included in his original vision of the film. Due to its difficulty and cost, this process of back-lit animation was not repeated for another feature film.

Sound design and creation for the film was assigned to Frank Serafine, who was responsible for the sound design on Star Trek: The Motion Picture in 1979. Tron was a 1983 Academy Awards nominee for Best Sound.

At one point in the film, a small entity called "Bit" advises Flynn with only the words "yes" and "no" created by a Votrax speech synthesizer.

BYTE wrote "Although this film is very much the personal expression of Steven Lisberger's vision, nevertheless [it] has certainly been a group effort".[10] More than 569 people were involved in the post-production work, including 200 inkers and hand-painters, 85 of them from Taiwan's Cuckoo's Nest Studio (unusually, for an English-language production, in the end credits the personnel were listed with their frames written in Chinese characters).[5]

This film features parts of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory; the multi-storey ENCOM laser bay was the target area for the SHIVA solid-state multi-beamed laser. Also, the stairway that Alan, Lora, and Flynn use to reach Alan's office is the stairway in Building 451 near the entrance to the main machine room. The cubicle scenes were shot in another room of the lab. At the time, Tron was the only movie to have scenes filmed inside this lab.[11]

The original script called for "good" programs to be colored yellow and "evil" programs (those loyal to Sark and the MCP) to be colored blue. Partway into production, this coloring scheme was changed to blue for good and red for evil, but some scenes were produced using the original coloring scheme: Clu, who drives a tank, has yellow circuit lines, and all of Sark's tank commanders are blue (but appear green in some presentations). Also, the light-cycle sequence shows the heroes driving yellow (Flynn), orange (Tron), and red (Ram) cycles, while Sark's troops drive blue cycles; similarly, Clu's tank is red, while tanks driven by crews loyal to Sark are blue.

Budgeting the production was difficult by reason of breaking new ground in response to additional challenges, including an impending Directors Guild of America strike and a fixed release date.[3] Disney predicted at least $400 million in domestic sales of merchandise, including an arcade game by Bally Midway and three Mattel Intellivision home video games.[5]

The producers also added Easter eggs: during the scene where Tron and Ram escape from the Light Cycle arena into the system, Pac-Man can be seen behind Sark (with the corresponding sounds from the Pac-Man arcade game being heard in the background), while a "Hidden Mickey" outline (located at time 01:12:29 on the re-release Blu-ray) can be seen below the solar sailer during the protagonists' journey.

Music

The soundtrack for Tron was written by pioneer electronic musician Wendy Carlos, who is best known for her album Switched-On Bach and for the soundtracks to many films, including A Clockwork Orange and The Shining. The music, which was the first collaboration between Carlos and her partner Annemarie Franklin,[12] featured a mix of an analog Moog synthesizer and Crumar's GDS digital synthesizer (complex additive and phase modulation synthesis), along with non-electronic pieces performed by the London Philharmonic Orchestra (hired at the insistence of Disney, which was concerned that Carlos might not be able to complete her score on time). Two additional musical tracks ("1990's Theme" and "Only Solutions") were provided by the American band Journey after British band Supertramp pulled out of the project. An album featuring dialogue, music and sound effects from the film was also released on LP by Disneyland Records in 1982.

Reception

Box office

Tron was released on July 9, 1982, in 1,091 theaters grossing USD $4 million on its opening weekend. It went on to make $33 million in North America,[13] which Disney saw as a disappointment, and led to the studio writing off a good chunk of its $17 million budget.[14]

Critical response

The film was well received by critics. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film four out of four stars and described the film as "a dazzling movie from Walt Disney in which computers have been used to make themselves romantic and glamorous. Here's a technological sound-and-light show that is sensational and brainy, stylish, and fun".[15] However, near the end of his review, he noted (in a positive tone), "This is an almost wholly technological movie. Although it's populated by actors who are engaging (Bridges, Cindy Morgan) or sinister (Warner), it is not really a movie about human nature. Like [the last two Star Wars films], but much more so, this movie is a machine to dazzle and delight us".[15] Ebert was so convinced that this film had not been given its due credit by both critics and audiences that he decided to close his first annual Overlooked Film Festival with a showing of Tron.[16] Tron was also featured in Siskel and Ebert's video pick of the week in 1993.[17]

InfoWorld's Deborah Wise was impressed, writing that "it is hard to believe the characters acted out the scenes on a darkened soundstage... We see characters throwing illuminated Frisbees, driving 'lightcycles' on a video-game grid, playing a dangerous version of jai alai and zapping numerous fluorescent tanks in arcade-game-type mazes. It's exciting, it's fun, and it's just what video-game fans and anyone with a spirit of adventure will love—despite plot weaknesses."[18]

On the other hand, Variety disliked the film and said in its review, "Tron is loaded with visual delights but falls way short of the mark in story and viewer involvement. Screenwriter-director Steven Lisberger has adequately marshalled a huge force of technicians to deliver the dazzle, but even kids (and specifically computer game geeks) will have a difficult time getting hooked on the situations".[19] In her review for The New York Times, Janet Maslin criticized the film's visual effects: "They're loud, bright and empty, and they're all this movie has to offer".[20] The Washington Post's Gary Arnold wrote, "Fascinating as they are as discrete sequences, the computer-animated episodes don't build dramatically. They remain a miscellaneous form of abstract spectacle".[21] In his review for the Globe and Mail, Jay Scott wrote, "It's got momentum and it's got marvels, but it's without heart; it's a visionary technological achievement without vision".[22]

As of July 2013, the movie review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes rated the film at 71% on its Tomatometer, based on the reviews of 48 critics. A consensus statement for the movie said, "Though perhaps not as strong dramatically as it is technologically, TRON is an original and visually stunning piece of science fiction that represents a landmark work in the history of computer animation."[23]

In the year it was released, the Motion Picture Academy refused to nominate Tron for a special-effects award because, according to director Steven Lisberger, "The Academy thought we cheated by using computers".[24] The film did, however, earn Oscar nominations in the categories of Best Costume Design and Best Sound (Michael Minkler, Bob Minkler, Lee Minkler, and James LaRue).[25]

Cultural effect

In 1997, Ken Perlin of the Mathematical Applications Group, Inc. won an Academy Award for Technical Achievement for his invention of Perlin noise for Tron.[26] In 2008, Tron was nominated for AFI's Top 10 Science Fiction Films list.[27]

The film, considered groundbreaking, has inspired several individuals in numerous ways. John Lasseter, head of Pixar and Disney's animation group, described how the film helped him see the potential of computer-generated imagery in the production of animated films stating "without Tron there would be no Toy Story."[28][29]

The music video of the song "Abiura di me" of the Italian rapper Caparezza is based on Tron. The two members of the French house music group Daft Punk, who scored the sequel, have held a joint, lifelong fascination with the film.[30]

Tron developed into a cult film and was ranked as 13th in a 2010 list of the top 20 cult films published by The Boston Globe.[31]

Books

A novelization of Tron was released in 1982, written by American science fiction novelist Brian Daley. It included eight pages of color photographs from the movie.[32] Also that year, Disney Senior Staff Publicist Michael Bonifer authored a book entitled The Art of Tron which covered aspects of the pre-production and post-production aspects of Tron.[33][34] A nonfiction book about the making of the original film, The Making of Tron: How Tron Changed Visual Effects and Disney Forever, was written by William Kallay and published in 2011.

Home media

Tron was originally released on VHS, Betamax, LaserDisc, and CED Videodisc in 1983. As with most video releases from the 1980s, the film was cropped to the 4:3 pan & scan format. The film saw multiple re-releases throughout the 1990s, most notably an "Archive Collection" LaserDisc box set,[35] which featured the first release of the film in its original widescreen 2.20:1 format.

Tron saw its first DVD release on May 19, 1998. This bare-bones release utilized the same non-anamorphic video transfer used in the Archive Collection LaserDisc set, and did not include any of the LD's special features. On January 15, 2002, the film received a 20th Anniversary Collector's Edition release in the form of a special 2-Disc DVD set. This set featured a new THX mastered anamorphic video transfer, and included all of the special features from the LD Archive Collection, plus an all-new 90 minute "Making of Tron" documentary.

To tie in with the home video release Tron: Legacy, the movie was finally re-released by Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment on Special Edition DVD and for the first time on Blu-ray Disc on April 5, 2011, with the subtitle "The Original Classic" to distinguish it from its sequel. Tron was also featured in a 5-Disc Blu-ray Combo with the 3D copy of Tron: Legacy. The film was re-released on Blu-ray and DVD in the UK on June 27, 2011.

Sequels

Tron: Legacy

On January 12, 2005, Disney announced it had hired screenwriters Brian Klugman and Lee Sternthal to write a sequel to Tron.[36] In 2008, director Joseph Kosinski negotiated to develop and direct TRON, described as "the next chapter" of the 1982 film and based on a preliminary teaser trailer shown at that year's San Diego Comic-Con, with Lisberger co-producing.[37] Filming began in Vancouver, British Columbia in April 2009.[38] During the 2009 Comic-Con, the title of the sequel was revealed to be changed to Tron: Legacy.[39][40] The second trailer (also with the [Tron: Legacy] logo) was released in 3D with Alice In Wonderland. A third trailer premiered at Comic-Con 2010 on July 22. At Disney's D23 Expo on September 10–13, 2009, they also debuted teaser trailers for Tron: Legacy as well as having light cycle and other props from the film there. The film was released on December 17, 2010, with Daft Punk composing the score.[41]

Tron 3

A third film is in the works with Garrett Hedlund and Boxleitner reprising their roles.

See also

- TRON command in BASIC (though Lisberger has stated that this is a coincidence and has nothing to do with the film title).<ref name="27 Things We Learned From the 'Tron" Commentary">Carr, Kevin. "27 Things We Learned from the 'Tron' Commentary". Film School Rejects. Archived from the original on 2015-05-09. Retrieved 2015-04-09.</ref>

- Simulated reality

- Demoscene

References

- ↑ Schneider, Michael (4 November 2010). "Disney XD orders 'Tron: Legacy' toon". Variety. Archived from the original on 2012-06-30. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Culhane, John (July 4, 1982). "Special Effects are Revolutionizing Film". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 2009-01-28.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 Patterson, Richard (August 1982). "The Making of Tron". American Cinematographer.

- ↑ "Interview: Justin Springer and Steven Lisberger, co-producers of Tron: Legacy". Archived from the original on 2012-09-15.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Ansen, David (July 5, 1982). "When You Wish Upon a Tron". Newsweek.

- ↑ "In70mm.com". Archived from the original on 2012-09-15.

- ↑ Interview with Harrison Ellenshaw, supplemental material on Tron DVD

- ↑ "The influence of Disney's Tron in filmmaking Tron and CG moviemaking". Archived from the original on 2012-07-07.

- ↑ The Making of Tron (DVD Feature)

- ↑ Sorensen, Peter (November 1982). "Tronic Imagery". BYTE. p. 48. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ↑ "The People of NIF: Rod Saunders: Each Day is an Adventure". Archived from the original on 2012-08-05.

- ↑ Moog, Robert (November 1982). "The Soundtrack of TRON" (PDF). Keyboard Magazine: 53–57. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ↑ "Tron". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 2012-07-22. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑ Stewart, James B. (2005). DisneyWar: The Battle for the Magic Kingdom (p. 45). New York: Simon & Schuster

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1982). "Tron". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑ "Roger Ebert's Overlooked Film Festival #1 Schedule". Archived from the original on 2012-07-10. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ↑ "Super Mario Bros. / What's Love Got To Do With It / 1993". siskelandebert.org. Retrieved 2012-11-16.

- ↑ Deborah Wise, "Unabashed fan and critics' critic talk about Disney's Tron," InfoWorld Vol. 4, No. 30 (Aug 2, 1982): 70-71.

- ↑ "Tron". Variety. January 1, 1982. Archived from the original on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑ Maslin, Janet (July 9, 1982). "Tron". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑ Arnold, Gary (July 10, 1982). "Duel of Two Disneys". Washington Post. pp. C1.

- ↑ Scott, Jay (July 10, 1982). "Tron Beautiful but Heartless". Globe and Mail.

- ↑ Tron at Rotten Tomatoes

- ↑ Helfand, Glen (January 9, 2002). "Tron 20th Anniversary". San Francisco Gate.

- ↑ "The 55th Academy Awards (1983) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on 2012-09-05. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- ↑ Kerman, Phillip. Macromedia Flash 8 @work: Projects and Techniques to Get the Job Done. Sams Publishing. 2006.

- ↑ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Ballot" (PDF). Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ↑ Thompson, Anne (December 9, 2010). "What Will Tron: Legacy's 3D VFX Look Like in 30 Years?". Tron Legacy VFX Special Effects in Tron Legacy. Popular Mechanics. Archived from the original on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- ↑ Lyons, Mike (November 1998). "Toon Story: John Lasseter's Animated Life". Animation World Magazine. Archived from the original on 2012-06-29. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- ↑ IGN Staff (12 October 2010). "Listen to Daft Punk in TRON: Legacy". IGN. Archived from the original on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

Having grown up with admiration of Disney's original 1982 film Tron...

- ↑ Boston.com Staff (August 17, 2006). "Top 20 cult films, according to our readers". boston.com (The Boston Globe). Archived from the original on 2012-07-30. Retrieved December 27, 2010.

- ↑ Daley, Brian (1 October 1982). Tron. New English Library Ltd. ISBN 0-450-05550-7.

- ↑ Bonifer, Michael (November 1982). The Art of Tron. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-45575-3.

- ↑ "Tron Sector Biography of Mike Bonifer". Archived from the original on 2008-06-09.

- ↑ "Tron — Archived Edition LaserDisc Box Set". LaserDisc Database. Archived from the original on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 2012-02-13.

- ↑ Fleming, Michael (January 12, 2005). "Mouse uploads Tron redo". Variety. Archived from the original on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑ Kit, Borys (September 11, 2007). "New Tron races on". Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 2008-06-15. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑ "Feature films currently filming in BC". Archived from the original on 2012-05-26.

- ↑ "Comic Con: Disney Panel, Tron 2 Revealed Live From Hall H!". Cinemablend.com. Archived from the original on 2012-09-04. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ↑ Roush, George (23 July 2009). "Comic-Con 2009: Disney Panel TRON Legacy & Alice In Wonderland!". Latino Review. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- ↑ Anderson, Kyle. "'Tron: Legacy' Soundtrack: Get Ready For The Game With Daft Punk". MTV. Archived from the original on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tron (film). |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Tron |

- Official website

- Tron at the Internet Movie Database

- Tron at the TCM Movie Database

- Tron at AllMovie

- Tron at Rotten Tomatoes

- Tron at Box Office Mojo

- Article about the CGI in Tron

- Tron 30th Anniversary Retrospective Retrieved January 2013

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||