Trienio Liberal

The Trienio Liberal (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈtɾjenjo liβeˈɾal], "Liberal Triennium") was a period of three years of liberal government in Spain. After the revolution of 1820 the movement spread quickly to the rest of Spain and the Spanish Constitution of 1812 was reinstated. The Triennium was a volatile period between liberals and conservatives in Spain, and constant political tensions between the two groups progressively weakened the government's authority. Finally in 1823, with the approval of the crown heads of Europe, a French army invaded Spain and reinstated the King's absolute power. This invasion is known in France as the "Spanish Expedition" (expédition d’Espagne), and in Spain as "The Hundred Thousand Sons of St. Louis".

The Revolution of Cabezas de San Juan

Spain's King Ferdinand VII provoked widespread unrest, particularly in the army, by refusing to accept the liberal Spanish Constitution of 1812. The King sought to reclaim the Spanish colonies in the Americas that had recently revolted successfully, consequently depriving Spain from an important source of revenue. In January 1820, soldiers assembled at Cadiz for an expedition to South America, angry over infrequent pay, bad food, and poor quarters, mutinied under the leadership of Colonel Rafael del Riego y Nuñez. Pledging fealty to the 1812 Constitution, they seized their commander. Subsequently the rebel forces moved to nearby San Fernando where they began preparations to march on the capital of Madrid.

Liberal government

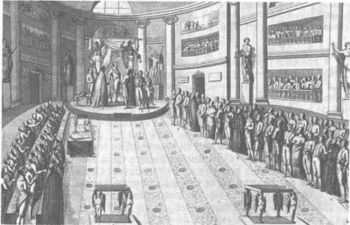

Despite the rebels' relative weakness, Ferdinand accepted the constitution on March 9, 1820, granting power to liberal ministers and ushering in the so-called Liberal Triennium (el Trienio Liberal), a period of popular rule. However, in this liberal atmosphere, political conspiracies of both right and left proliferated in Spain, as was the case across much of Europe. Liberal revolutionaries stormed the King's palace and seized Ferdinand VII who was a prisoner of the Cortes in all but name for the next three years. During this time Ferdinand retired to Aranjuez. The elections to the Cortes Generales in 1822 were won by Rafael del Riego. Ferdinand's supporters set themselves up at Urgell, took up arms and put in place an absolutist regency. Ferdinand's supporters, accompanied by the Royal Guard, staged an uprising in Madrid which was subdued by forces supporting the new government and its constitution. Despite the defeat of Ferdinand's supporters at Madrid, civil war erupted in the regions of Castile, Toledo, and Andalusia.

French intervention and restoration of Absolutism

In 1822, Ferdinand VII applied the terms of the Congress of Vienna, lobbied for the assistance of the other absolute monarchs of Europe, in the process joining the Holy Alliance formed by Russia, Prussia, Austria and France to restore absolutism. In France, the ultra-royalists pressured Louis XVIII to intervene. To temper their counter-revolutionary ardor, the Duc de Richelieu deployed troops along the Pyrenees Mountains along the France-Spain border, charging them with halting the spread of Spanish liberalism and the "yellow fever" from encroaching into France. In September 1822 this "cordon sanitaire" became an observation corps and then very quickly transformed itself into a military expedition.

The Holy Alliance (Russia, Austria and Prussia) refused Ferdinand's request for help, but the Quintuple Alliance (Britain, France, Russia, Prussia and Austria) at the Congress of Verona in October 1822 gave France a mandate to intervene and restore the Spanish monarchy. On 22 January 1823, a secret treaty was signed at the congress of Verona, allowing France to invade Spain to restore Ferdinand VII as an absolute monarch. With this agreement from the Holy Alliance, on 28 January 1823 Louis XVIII announced that "a hundred thousand Frenchmen are ready to march, invoking the name of Saint Louis, to safeguard the throne of Spain for a grandson of Henry IV of France".

Bibliography

In French

- Encyclopédie Universalis, Paris, Volume 18, 2000

- Larousse, tome 1, 2, 3, Paris, 1998

- Caron, Jean-Claude, La France de 1815 à 1848, Paris, Armand Colin, coll. « Cursus », 2004, 193 p.

- Corvisier, André, Histoire militaire de la France, de 1715 à 1871, tome 2, Paris, Presses universitaires de France, "Quadrige" collection, 1998, 627 p.

- Demier, Francis, La France du XIXe 1814-1914, Seuil, 2000, 606 p.

- Dulphy, Anne, Histoire de l'Espagne de 1814 à nos jours, le défi de la modernisation, Paris, Armand Colin, "128" collection, 2005, 127 p.

- Duroselle, Jean-Baptiste, L'Europe de 1815 à nos jours : vie politique et relation internationale, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, "Nouvelle clio" collection, 1967, 363 p.

- Garrigues, Jean, Lacombrade, Philippe, La France au 19e siècle, 1814-1914, Paris, Armand Colin, "Campus" collection, 2004, 191 p.

- Lever, Evelyne, Louis XVIII, Paris, Fayard, 1998, 597 p.

- Jean Sarrailh, Un homme d'état espagnol: Martínez de la Rosa (1787–1862) (Paris, 1930)

In Spanish

- Miguel Artola Gallego, La España de Fernando VII (Madrid, 1968)

- Jonathan Harris, 'Los escritos de codificación de Jeremy Bentham y su recepción en el primer liberalismo español', Télos. Revista Iberoamericana de Estudios Utilitaristas 8 (1999), 9-29

- W. Ramírez de Villa-Urrutia, Fernando VII, rey constitucional. Historia diplomática de España de 1820 a 1823 (Madrid, 1922)

In English

- Raymond Carr, Spain 1808-1975 (Oxford, 1982, 2nd ed.)

- Charles W. Fehrenbach, ‘Moderados and Exaltados: the liberal opposition to Ferdinand VII, 1814-1823’, Hispanic American Historical Review 50 (1970), 52-69

- Jonathan Harris, 'An English utilitarian looks at Spanish American independence: Jeremy Bentham's Rid Yourselves of Ultramaria', The Americas 53 (1996), 217-33

- Jarrett, Mark (2013). The Congress of Vienna and its Legacy: War and Great Power Diplomacy after Napoleon. London: I. B. Tauris & Company, Ltd. ISBN 978-1780761169.