Tridiagonal matrix algorithm

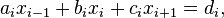

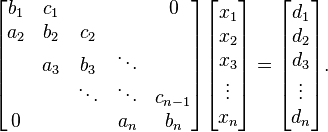

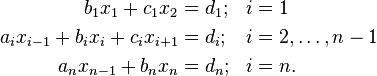

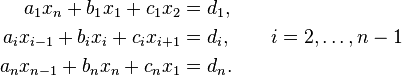

In numerical linear algebra, the tridiagonal matrix algorithm, also known as the Thomas algorithm (named after Llewellyn Thomas), is a simplified form of Gaussian elimination that can be used to solve tridiagonal systems of equations. A tridiagonal system for n unknowns may be written as

where  and

and  .

.

For such systems, the solution can be obtained in  operations instead of

operations instead of  required by Gaussian elimination. A first sweep eliminates the

required by Gaussian elimination. A first sweep eliminates the  's, and then an (abbreviated) backward substitution produces the solution. Examples of such matrices commonly arise from the discretization of 1D Poisson equation (e.g., the 1D diffusion problem) and natural cubic spline interpolation; similar systems of matrices arise in tight binding physics or nearest neighbor effects models.

's, and then an (abbreviated) backward substitution produces the solution. Examples of such matrices commonly arise from the discretization of 1D Poisson equation (e.g., the 1D diffusion problem) and natural cubic spline interpolation; similar systems of matrices arise in tight binding physics or nearest neighbor effects models.

Thomas' algorithm is not stable in general, but is so in several special cases, such as when the matrix is diagonally dominant or symmetric positive definite;[1][2] for a more precise characterization of stability of Thomas' algorithm, see Higham Theorem 9.12.[3] If stability is required in the general case, Gaussian elimination with partial pivoting (GEPP) is recommended instead.[2]

Method

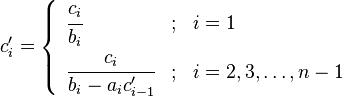

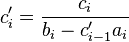

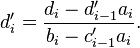

The forward sweep consists of modifying the coefficients as follows, denoting the new modified coefficients with primes:

and

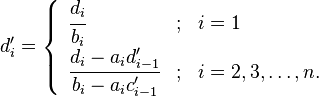

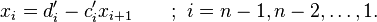

The solution is then obtained by back substitution:

Algorithm (programmatic)

The following is an example of the implementation of this algorithm in the C programming language.

/* * tridiagonal: Thomas' algorithm implementation *Inputs: a,b,c are L,D,U vectors respectively * d is coefficient vector; is overwritten with solution vector * len is length of b et d *Outputs: Returns 0 (if you want to signal an error at some point, return something else) * As above, d is overwritten with answer vector. * a,b also modified *Note: For simplicity's sake b is overwritten with successive denominators (see Method above); * it isn't hard to change this if you so wish *Note 2: We don't check for diagonal dominance, etc.; * this is not guaranteed stable */ int tridiagonal (double *c, double *b, double *a, double *d, int len) { int i; /*Forward sweep*/ *a /= *b; for(i=1;i<len-1;i++) { b[i] -= (a[i-1]*c[i-1]); a[i] /=b[i]; } b[len-1] -= (a[len-2]*c[len-2]); for(i=1;i<len;i++) d[i] -= (d[i-1]*a[i-1]); d[len-1] /= b[len-1]; /*Backward sweep*/ for(i=len-2;i>=0;i--) { d[i] -= (d[i+1]*c[i]); d[i] /= b[i]; } return 0; }

Derivation

The derivation of the tridiagonal matrix algorithm involves manually performing some specialized Gaussian elimination in a generic manner.

Suppose that the unknowns are  , and that the equations to be solved are:

, and that the equations to be solved are:

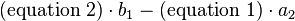

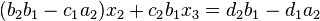

Consider modifying the second ( ) equation with the first equation as follows:

) equation with the first equation as follows:

which would give:

and the effect is that  has been eliminated from the second equation. Using a similar tactic with the modified second equation on the third equation yields:

has been eliminated from the second equation. Using a similar tactic with the modified second equation on the third equation yields:

This time  was eliminated. If this procedure is repeated until the

was eliminated. If this procedure is repeated until the  row; the (modified)

row; the (modified)  equation will involve only one unknown,

equation will involve only one unknown,  . This may be solved for and then used to solve the

. This may be solved for and then used to solve the  equation, and so on until all of the unknowns are solved for.

equation, and so on until all of the unknowns are solved for.

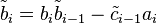

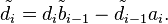

Clearly, the coefficients on the modified equations get more and more complicated if stated explicitly. By examining the procedure, the modified coefficients (notated with tildes) may instead be defined recursively:

To further hasten the solution process,  may be divided out (if there's no division by zero risk), the newer modified coefficients notated with a prime will be:

may be divided out (if there's no division by zero risk), the newer modified coefficients notated with a prime will be:

This gives the following system with the same unknowns and coefficients defined in terms of the original ones above:

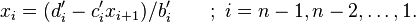

The last equation involves only one unknown. Solving it in turn reduces the next last equation to one unknown, so that this backward substitution can be used to find all of the unknowns:

Variants

In some situations, particularly those involving periodic boundary conditions, a slightly perturbed form of the tridiagonal system may need to be solved:

In this case, we can make use of the Sherman-Morrison formula to avoid the additional operations of Gaussian elimination and still use the Thomas algorithm. The method requires solving a modified non-cyclic version of the system for both the input and a sparse corrective vector, and then combining the solutions. This can be done efficiently if both solutions are computed at once, as the forward portion of the pure tridiagonal matrix algorithm can be shared.

In other situations, the system of equations may be block tridiagonal (see block matrix), with smaller submatrices arranged as the individual elements in the above matrix system(e.g., the 2D Poisson problem). Simplified forms of Gaussian elimination have been developed for these situations.

The textbook Numerical Mathematics by Quarteroni, Sacco and Saleri, lists a modified version of the algorithm which avoids some of the divisions (using instead multiplications), which is beneficial on some computer architectures.

References

| The Wikibook Algorithm Implementation has a page on the topic of: Tridiagonal matrix algorithm |

- ↑ Pradip Niyogi (2006). Introduction to Computational Fluid Dynamics. Pearson Education India. p. 76. ISBN 978-81-7758-764-7.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Biswa Nath Datta (2010). Numerical Linear Algebra and Applications, Second Edition. SIAM. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-89871-765-5.

- ↑ Nicholas J. Higham (2002). Accuracy and Stability of Numerical Algorithms: Second Edition. SIAM. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-89871-802-7.

- Conte, S.D., and deBoor, C. (1972). Elementary Numerical Analysis. McGraw-Hill, New York. ISBN 0070124469.

- This article incorporates text from the article Tridiagonal_matrix_algorithm_-_TDMA_(Thomas_algorithm) on CFD-Wiki that is under the GFDL license.

- Press, WH; Teukolsky, SA; Vetterling, WT; Flannery, BP (2007). "Section 2.4". Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing (3rd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88068-8

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||