Tricyclic antidepressant overdose

| Tricyclic antidepressant overdose | |

|---|---|

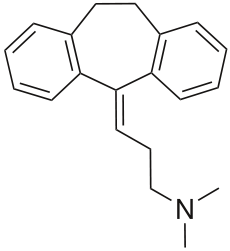

Chemical structure of the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | T43.0 |

| ICD-9 | 969.0 |

| eMedicine | article/1010089 |

Tricyclic antidepressant overdose is caused by excessive use or overdose of a tricyclic antidepressant drug. It is a significant cause of fatal drug poisoning. The severe morbidity and mortality associated with these drugs is well documented due to their cardiovascular and neurological toxicity. Additionally, it is a serious problem in the pediatric population due to their potential toxicity[1] and the availability of these in the home when prescribed for bed wetting and depression.

Signs and symptoms

The peripheral autonomic nervous system, central nervous system and the heart are the main systems that are affected following overdose.[2] Initial or mild symptoms typically develop within 2 hours and include tachycardia, drowsiness, a dry mouth, nausea and vomiting, urinary retention, confusion, agitation, and headache.[3] More severe complications include hypotension, cardiac rhythm disturbances, hallucinations, and seizures. Electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities are frequent and a wide variety of cardiac dysrhythmias can occur, the most common being sinus tachycardia and intraventricular conduction delay resulting in prolongation of the QRS complex and the PR/QT intervals.[4] Seizures, cardiac dysrhythmias, and apnea are the most important life threatening complications.[3]

Toxicity

Tricyclics have a narrow therapeutic index, i.e., the therapeutic dose is close to the toxic dose.[3] In the medical literature the lowest reported toxic dose is 6.7 mg per kg body weight. Although there are differences in toxicity with the drug class, ingestions of 10 to 20 mg per kilogram of body weight are a risk for moderate to severe poisoning, however, doses ranging from 1.5 to 5 mg/kg may even present a risk. Most poison control centers refer any case of TCA poisoning (especially in children) to a hospital for monitoring.[5] Factors that increase the risk of toxicity include advancing age, cardiac status, and concomitant use of other drugs.[6] However, serum drug levels are not useful for evaluating risk of arrhythmia or seizure in tricyclic overdose.[7]

Pathophysiology

Most of the toxic effects of TCAs are caused by four major pharmacological effects. TCAs have anticholinergic effects, cause excessive blockade of norepinephrine reuptake at the preganglionic synapse, direct alpha adrenergic blockade, and importantly they block sodium membrane channels with slowing of membrane depolarization, thus having quinidine-like effects on the myocardium.[2]

Treatment

Initial treatment of an acute overdose includes gastric decontamination of the patient. This is achieved by administering activated charcoal lavage which adsorbs the drug in the gastrointestinal tract either orally or via a nasogastric tube. Activated charcoal is most useful if given within 1 to 2 hours of ingestion.[8] Other decontamination methods such as stomach pumps, ipecac induced emesis, or whole bowel irrigation are not recommended in TCA poisoning.[9][10]

Symptomatic patients are usually monitored in an intensive care unit for a minimum of 12 hours, with close attention paid to maintenance of the airways, along with monitoring of blood pressure, arterial pH, and continuous ECG monitoring.[2] Supportive therapy is given if necessary, including respiratory assistance, maintenance of body temperature, and administration of intravenous sodium bicarbonate as an antidote, which has been shown to be an effective treatment for resolving the metabolic acidosis and cardiovascular complications of TCA poisoning. If sodium bicarbonate therapy fails to improve cardiac symptoms, conventional antidysrhythmic drugs such as phenytoin and magnesium can be used to reverse any cardiac abnormalities. However, no benefit has been shown from Class 1 antiarrhythmic drugs; it appears they worsen the sodium channel blockade, slow conduction velocity, and depress contractility and should be avoided in TCA poisoning.[11] Hypotension is initially treated with fluids along with bicarbonate to reverse metabolic acidosis (if present), if the patient remains hypotensive despite fluids then further measures such as the administration of epinephrine, norepinephrine, or dopamine can be used to increase blood pressure.[11] Another potentially severe symptom is seizures: Seizures often resolve without treatment but administration of a benzodiazepine or other anticonvulsive may be required for persistent muscular overactivity. There is no role for physostigmine in the treatment of tricyclic toxicity as it may increase cardiac toxicity and cause seizures.[2] In cases of severe TCA overdose that are refractory to conventional therapy, intravenous lipid emulsion therapy has been reported to improve signs and symptoms in moribund patients suffering from toxicities involving several types of lipophilic substances, therefore lipids may have a role in treating severe cases of refractory TCA overdose.[12]

Tricyclic antidepressants are highly protein bound and have a large volume of distribution; therefore removal of these compounds from the blood with hemodialysis, hemoperfusion or other techniques are unlikely to be of any significant benefit.[10]

Epidemiology

Studies in the 1990s in Australia and the United Kingdom showed that between 8 and 12% of drug overdoses were following TCA ingestion. TCAs may be involved in up to 33% of all fatal poisonings, second only to analgesics.[13][14] Another study reported 95% of deaths from antidepressants in England and Wales between 1993 and 1997 were associated with tricyclic antidepressants, particularly dothiepin and amitriptyline. It was determined there were 5.3 deaths per 100,000 prescriptions.[15] Sodium channel blockers such as Dilantin should not be used in the treatment of TCA overdose as the Na+ blockade will increase the QTI.

References

- ↑ Rosenbaum T, Kou M (2005). "Are one or two dangerous? Tricyclic antidepressant exposure in toddlers". J Emerg Med 28 (2): 169–74. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2004.08.018. PMID 15707813.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Kerr G, McGuffie A, Wilkie S (2001). "Tricyclic antidepressant overdose: a review". Emerg Med J 18 (4): 236–41. doi:10.1136/emj.18.4.236. PMC 1725608. PMID 11435353.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Woolf AD, Erdman AR, Nelson LS, Caravati EM, Cobaugh DJ, Booze LL, Wax PM, Manoguerra AS, Scharman EJ, Olson KR, Chyka PA, Christianson G, Troutman WG (2007). "Tricyclic antidepressant poisoning: an evidence-based consensus guideline for out-of-hospital management". Clin Toxicol (Phila) 45 (3): 203–33. doi:10.1080/15563650701226192. PMID 17453872.

- ↑ Thanacoody H, Thomas S (2005). "Tricyclic antidepressant poisoning : cardiovascular toxicity". Toxicol Rev 24 (3): 205–14. doi:10.2165/00139709-200524030-00013. PMID 16390222.

- ↑ McFee R, Mofenson H, Caraccio T (2000). "A nationwide survey of the management of unintentional-low dose tricyclic antidepressant ingestions involving asymptomatic children: implications for the development of an evidence-based clinical guideline". J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 38 (1): 15–9. doi:10.1081/CLT-100100910. PMID 10696919.

- ↑ Preskorn S, Irwin H (1982). "Toxicity of tricyclic antidepressants--kinetics, mechanism, intervention: a review". J Clin Psychiatry 43 (4): 151–6. PMID 7068546.

- ↑ Boehnert M, Lovejoy F (1985). "Value of the QRS duration versus the serum drug level in predicting seizures and ventricular arrhythmias after an acute overdose of tricyclic antidepressants". N Engl J Med 313 (8): 474–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM198508223130804. PMID 4022081.

- ↑ Dart, RC (2004). Medical toxicology. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins. pp. 834–43. ISBN 0-7817-2845-2.

- ↑ Teece S, Hogg K (2003). "Gastric lavage in tricyclic antidepressant overdose". Emerg Med J 20 (1): 64. doi:10.1136/emj.20.1.64. PMC 1726003. PMID 12533375.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Dargan P, Colbridge M, Jones A (2005). "The management of tricyclic antidepressant poisoning : the role of gut decontamination, extracorporeal procedures and fab antibody fragments". Toxicol Rev 24 (3): 187–94. doi:10.2165/00139709-200524030-00011. PMID 16390220.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Bradberry S, Thanacoody H, Watt B, Thomas S, Vale J (2005). "Management of the cardiovascular complications of tricyclic antidepressant poisoning : role of sodium bicarbonate". Toxicol Rev 24 (3): 195–204. doi:10.2165/00139709-200524030-00012. PMID 16390221.

- ↑ Goldfrank's Toxicological Emergencies 9th Edition

- ↑ Thomas S, Bevan L, Bhattacharyya S, Bramble M, Chew K, Connolly J, Dorani B, Han K, Horner J, Rodgers A, Sen B, Tesfayohannes B, Wynne H, Bateman D (1996). "Presentation of poisoned patients to accident and emergency departments in the north of England". Hum Exp Toxicol 15 (6): 466–70. doi:10.1177/096032719601500602. PMID 8793528.

- ↑ Buckley N, Whyte I, Dawson A, McManus P, Ferguson N (1995). "Self-poisoning in Newcastle, 1987-1992". Med J Aust 162 (4): 190–3. PMID 7877540.

- ↑ Shah R, Uren Z, Baker A, Majeed A (October 2001). "Deaths from antidepressants in England and Wales 1993-1997: analysis of a new national database". Psychol Med 31 (7): 1203–10. doi:10.1017/s0033291701004548. PMID 11681546.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||