Tres militiae

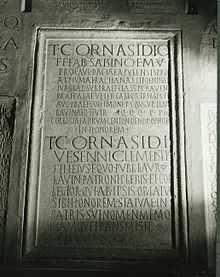

* prefect of Cohors I Montanorum in Pannonia;

* military tribune of Legio II Augusta in Britain;

* prefect of Ala veterana Gallorum in Egypt[1]

The tres militiae ("three military posts") was a career progression of the Roman Imperial army for men of the equestrian order. It developed as an alternative to the cursus honorum of the senatorial order for enabling the social mobility of equestrians and identifying those with the aptitude for administration. The three posts, typically held over a period of two to four years, were prefect of a cohort, military tribune, and prefect of an ala (wing).[2]

Men who passed through the tres militiae often became prefect of the food supply (Praefectus annonae), prefect of Egypt, or praetorian prefects, the highest prefectures available to equestrians.[3]

The emperor Trajan played a major role in establishing a regular career track for equestrians.[4] The first of the tres militiae was command as a prefect of a cohors quingenaria, one of approximately 150 auxiliary units of 500 men from the provinces.[5] Promotion required a transfer to a legion with the rank of tribunus angusticlavus, "military tribune of the narrow stripe," referring to the narrower width of the clavus (reddish-purple stripe) that distinguished the toga of an equestrian from that of a senator.[6] Each legion had five angusticlavi, but even with about 30 legions, there were probably only 20 or so vacancies each year.[7] An alternative post for the second militia was as auxiliary tribune with a cohors milliaria, one of 30 regiments of a thousand men each.[8] The third militia was prefect of an ala, one of 70 cavalry wings of 500 men each. In some exceptional cases, a man might receive a fourth promotion as prefect of a thousand-man ala, though fewer than ten such alae existed.[9]

A man would be in his mid-thirties or older at the conclusion of his tres militiae,[10] which could boost his career in politics or business at home. Some men instead moved on to posts in Imperial administration,[11] especially as procurator.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ CIL IX 5439.

- ↑ Andrew Fear, "War and Society," in The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare: Rome from the Late Repblic to the Late Empire (Cambridge University Press, 2007), vol. 2, pp. 214–215; Julian Bennett, Trajan: Optimus Princeps (Indiana University Press, 1997, 2001, 2nd ed.), p. 5.

- ↑ CAH p. 214.

- ↑ Bennett, Trajan, p. 5.

- ↑ Bennett, Trajan, p. 5.

- ↑ Bennett, Trajan, p. 5.

- ↑ Bennett, Trajan, p. 5.

- ↑ Bennett, Trajan, p. 5.

- ↑ Bennett, Trajan, p. 5.

- ↑ Bennett, Trajan, p. 5.

- ↑ Bennett, Trajan, p. 5.

- ↑ Elio Lo Cascio, "The Emperor and His Administration," in The Cambridge Ancient History: The Crisis of Empire, A.D. 193–337 (Cambridge University Press, 2005), vol. 12, p. 149.