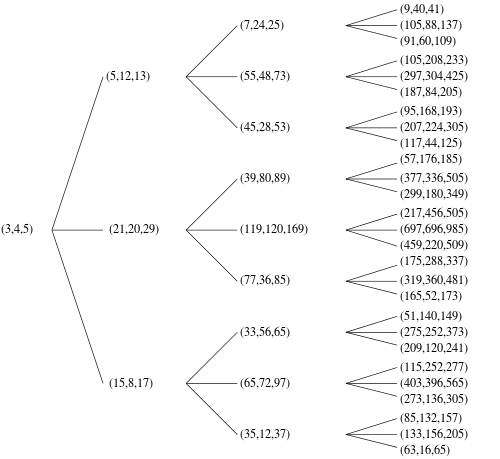

Tree of primitive Pythagorean triples

In mathematics, a Pythagorean triple is a set of three positive integers a, b, and c having the property that they can be respectively the two legs and the hypotenuse of a right triangle, thus satisfying the equation  ; the triple is said to be primitive if and only if a, b, and c share no common divisor. The set of all primitive Pythagorean triples has the structure of a rooted tree, specifically a ternary tree, in a natural way. This was first discovered by B. Berggren in 1934.[1]

; the triple is said to be primitive if and only if a, b, and c share no common divisor. The set of all primitive Pythagorean triples has the structure of a rooted tree, specifically a ternary tree, in a natural way. This was first discovered by B. Berggren in 1934.[1]

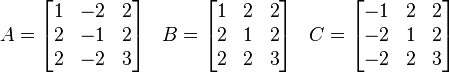

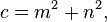

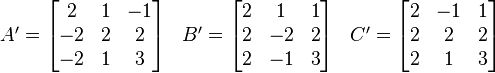

F. J. M. Barning showed[2] that when any of the three matrices

is multiplied on the right by a column vector whose components form a Pythagorean triple, then the result is another column vector whose components are a different Pythagorean triple. If the initial triple is primitive, then so is the one that results. Thus each primitive Pythagorean triple has three "children". All primitive Pythagorean triples are descended in this way from the triple (3 ,4, 5), and no primitive triple appears more than once. The result may be graphically represented as an infinite ternary tree with (3, 4, 5) at the root node (see classic tree at right). This tree also appeared in papers of A. Hall in 1970[3] and A. R. Kanga in 1990.[4]

Proofs

Presence of exclusively primitive Pythagorean triples

It can be shown inductively that the tree contains primitive Pythagorean triples and nothing else by showing that starting from a primitive Pythagorean triple, such as is present at the initial node with (3, 4, 5), each generated triple is both Pythagorean and primitive.

Preservation of the Pythagorean property

If any of the above matrices, say A, is applied to a triple (a, b, c)T having the Pythagorean property a2+b2=c2 to obtain a new triple (d, e, f)T = A(a, b, c)T, this new triple is also Pythagorean. This can be seen by writing out each of d, e, and f as the sum of three terms in a, b, and c, squaring each of them, and substituting c2=a2+b2 to obtain f2=d2+e2. This holds for B and C as well as for A.

Preservation of primitivity

The matricies A, B, and C are all unimodular—that is, they have only integer entries and their determinants are ±1. Thus their inverses are also unimodular and in particular have only integer entries. So if any one of them, for example A, is applied to a primitive Pythagorean triple (a, b, c)T to obtain another triple (d, e, f)T, we have (d, e, f)T = A(a, b, c)T and hence (a, b, c)T = A−1(d, e, f)T. If any prime factor were shared by any two of (and hence all three of) d, e, and f then by this last equation that prime would also divide each of a, b, and c. So if a, b, and c are in fact pairwise coprime, then d, e, and f must be pairwise coprime as well. This holds for B and C as well as for A.

Presence of every primitive Pythagorean triple exactly once

To show that the tree contains every primitive Pythagorean triple, but no more than once, it suffices to show that for any such triple there is exactly one path back through the tree to the starting node (3, 4, 5). This can be seen by applying in turn each of the unimodular inverse matrices A−1, B−1, and C−1 to an arbitrary primitive Pythagorean triple (d, e, f), noting that by the above reasoning primitivity and the Pythagorean property are retained, and noting that for any triple larger than (3, 4, 5) exactly one of the inverse transition matrices yields a new triple with all positive entries (and a smaller hypotenuse). By induction, this new valid triple itself leads to exactly one smaller valid triple, and so forth. By the finiteness of the number of smaller and smaller potential hypotenuses, eventually (3, 4, 5) is reached. This proves that (d, e, f) does in fact occur in the tree, since it can be reached from (3, 4, 5) by reversing the steps; and it occurs uniquely because there was only one path from (d, e, f) to (3, 4, 5).

Properties

The transformation using matrix A, if performed repeatedly from (a, b, c) = (3, 4, 5), preserves the feature b + 1 = c; matrix B preserves a – b = ±1 starting from (3, 4, 5); and matrix C preserves the feature a + 2 = c starting from (3, 4, 5).

A geometric interpretation for this tree involves the excircles present at each node. The three children of any parent triangle “inherit” their inradii from the parent: the parent’s excircle radii become the inradii for the next generation.[5]:p.7 For example, parent ( 3, 4, 5) has excircle radii equal to 2, 3, and 6. These are precisely the inradii of the three children (5, 12, 13), (15, 8, 17) and (21, 20, 29) respectively.

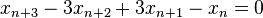

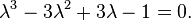

If either of A or C is applied repeatedly from any Pythagorean triple used as an initial condition, then the dynamics of any of a, b, and c can be expressed as the dynamics of x in

which is patterned on the matrices' shared characteristic equation

If B is applied repeatedly, then the dynamics of any of a, b, and c can be expressed as the dynamics of x in

which is patterned on the characteristic equation of B.[6]

Moreover, an infinitude of other third-order univariate difference equations can be found by multiplying any of the three matrices together an arbitrary number of times in an arbitrary sequence. For instance, the matrix D = CB moves one out the tree by two nodes (across, then down) in a single step; the characteristic equation of D provides the pattern for the third-order dynamics of any of a, b, or c in the non-exhaustive tree formed by D.

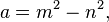

Alternative methods of generating the tree

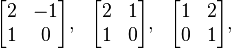

Another approach to the dynamics of this tree[7] relies on the standard formula for generating all primitive Pythagorean triples:

with m > n > 0 and m and n coprime and of opposite parity. Pairs (m, n) can be iterated by pre-multiplying them (expressed as a column vector) by any of

each of which preserves the inequalities, coprimeness, and opposite parity. The resulting ternary tree contains every such (m, n) pair exactly once, and when converted into (a, b, c) triples it becomes identical to the tree described above.

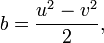

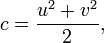

Another way of using two underlying parameters to generate the tree of triples[8] uses an alternative formula for all primitive triples:

with u > v > 0 and u and v coprime and both odd. Pairs (u, v) can be iterated by pre-multiplying them (expressed as a column vector) by any of the above 2 × 2 matrices, all three of which preserve the inequalities, coprimeness, and the odd parity of both elements. When this process is begun at (3, 1), the resulting ternary tree contains every such (u, v) pair exactly once, and when converted into (a, b, c) triples it becomes identical to the tree described above.

A different tree

A different tree found by Price[5] may be produced in a similar way using matrices A',B',C' shown below. (See Pythagorean triples by use of matrices and linear transformations.)

Notes and references

- ↑ B. Berggren, "Pytagoreiska trianglar" (in Swedish), Elementa: Tidskrift för elementär matematik, fysik och kemi 17 (1934), 129–139. See page 6 for the rooted tree.

- ↑ Barning, F. J. M. (1963), "Over pythagorese en bijna-pythagorese driehoeken en een generatieproces met behulp van unimodulaire matrices" (in Dutch), Math. Centrum Amsterdam Afd. Zuivere Wisk. ZW-011: 37, http://oai.cwi.nl/oai/asset/7151/7151A.pdf

- ↑ A. Hall, "Genealogy of Pythagorean Triads", The Mathematical Gazette, volume 54, number 390, December, 1970, pages 377–9.

- ↑ Kanga, A. R., "The family tree of Pythagorean triples," Bulletin of the Institute of Mathematics and its Applications 26, January/February 1990, 15–17.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Price, H. Lee (2008). "The Pythagorean Tree: A New Species". arXiv:0809.4324.

- ↑ Mitchell, Douglas W., "Feedback on 92.60", Mathematical Gazette 93, July 2009, 358–9.

- ↑ Saunders, Robert A.; Randall, Trevor (July 1994), "The family tree of the Pythagorean triplets revisited", Mathematical Gazette 78: 190–193, JSTOR 3618576.

- ↑ Mitchell, Douglas W., "An alternative characterisation of all primitive Pythagorean triples", Mathematical Gazette 85, July 2001, 273–275.

External links

- The Trinary Tree(s) underlying Primitive Pythagorean Triples at cut-the-knot

- Frank R. Bernhart, and H. Lee Price, "Pythagoras' garden, revisited", Australian Senior Mathematics Journal 01/2012; 26(1):29-40.