Tree (set theory)

In set theory, a tree is a partially ordered set (T, <) such that for each t ∈ T, the set {s ∈ T : s < t} is well-ordered by the relation <. Frequently trees are assumed to have only one root (i.e. minimal element), as the typical questions investigated in this field are easily reduced to questions about single-rooted trees.

Definition

A tree is a partially ordered set (poset) (T, <) such that for each t ∈ T, the set {s ∈ T : s < t} is well-ordered by the relation <. In particular, each well-ordered set (T, <) is a tree. For each t ∈ T, the order type of {s ∈ T : s < t} is called the height of t (denoted ht(t, T)). The height of T itself is the least ordinal greater than the height of each element of T. A root of a tree T is an element of height 0. Frequently trees are assumed to have only one root.

Trees with a single root in which each element has finite height can be naturally viewed as rooted trees in the sense of graph-theory, or of theoretical computer science: there is an edge from x to y if and only if y is a direct successor of x (i.e., x<y, but there is no element between x and y). However, if T is a tree of height > ω, then there is no natural edge relation that will make T a tree in the sense of graph theory. For example, the set  does not have a natural edge relationship, as there is no predecessor to ω.

does not have a natural edge relationship, as there is no predecessor to ω.

A branch of a tree is a maximal chain in the tree (that is, any two elements of the branch are comparable, and any element of the tree not in the branch is incomparable with at least one element of the branch). The length of a branch is the ordinal that is order isomorphic to the branch. For each ordinal α, the α-th level of T is the set of all elements of T of height α. A tree is a κ-tree, for an ordinal number κ, if and only if it has height κ and every level has size less than the cardinality of κ. The width of a tree is the supremum of the cardinalities of its levels.

Single-rooted trees of height ≤ ω forms a meet-semilattice, where meet (common ancestor) is given by maximal element of intersection of ancestors, which exists as the set of ancestors is non-empty and finite well-ordered, hence has a maximal element. Without a single root, the intersection of parents can be empty (two elements need not have common ancestors), for example  where the elements are not comparable; while if there are an infinite number of ancestors there need not be a maximal element – for example,

where the elements are not comparable; while if there are an infinite number of ancestors there need not be a maximal element – for example,  where

where  are not comparable.

are not comparable.

Properties

There are some fairly simply stated yet hard problems in infinite tree theory. Examples of this are the Kurepa conjecture and the Suslin conjecture. Both of these problems are known to be independent of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory. König's lemma states that every ω-tree has an infinite branch. On the other hand, it is a theorem of ZFC that there are uncountable trees with no uncountable branches and no uncountable levels; such trees are known as Aronszajn trees. A κ-Suslin tree is a tree of height κ which has no chains or antichains of size κ. In particular, if κ is singular (i.e. not regular) then there exists a κ-Aronszajn tree and a κ-Suslin tree. In fact, for any infinite cardinal κ, every κ-Suslin tree is a κ-Aronszajn tree (the converse does not hold).

The Suslin conjecture was originally stated as a question about certain total orderings but it is equivalent to the statement: Every tree of height ω1 has an antichain of cardinality ω1 or a branch of length ω1.

Tree (automata theory)

Following definition of a tree is slightly different from the above formalism. For example, each node of the tree is a word over set of natural numbers (ℕ), which helps this definition to be used in automata theory.

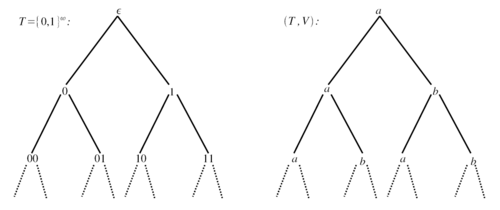

A tree is a set T ⊆ ℕ* such that if t.c ∈ T, with t ∈ ℕ* and c ∈ ℕ, then t ∈ T and t.c1 ∈ T for all 0 ≤ c1 < c. The elements of T are known as nodes, and the empty word ε is the (single) root of T. For every t ∈ T, the element t.c ∈ T is a successor of t in direction c. The number of successors of t is called its degree or arity, and represented as d(t). A node is a leaf if it has no successors. If every node of a tree has finitely many successors, then it is called a finitely, otherwise an infinitely branching tree. A path π is a subset of T such that ε ∈ π and for every t ∈ T, either t is a leaf or there exists a unique c ∈ ℕ such that t.c ∈ π. A path may be a finite or infinite set. If all paths of a tree are finite then the tree is called finite, otherwise infinite. A tree is called fully infinite if all its paths are infinite. Given an alphabet Σ, a Σ-labeled tree is a pair (T,V), where T is a tree and V: T → Σ maps each node of T to a symbol in Σ. A labeled tree formally defines a commonly used term tree structure. A set of labeled trees is called a tree language.

A tree is called ranked if there is an order among the successors of each of its nodes. Above definition of tree naturally suggests an order among the successors, which can be used to make the tree ranked. Sometimes, an extra function Ar: Σ → ℕ is defined. This function associates a fixed arity to each symbol of the alphabet. In this case, each t ∈ T has to satisfy Ar(V(t)) = d(t).

For example, above definition is used in the definition of an infinite tree automaton.

Example

Let T = {0,1}* and Σ = {a,b}. We define a labeling function V as follows: the labeling for the root node is V(ε) = a and, for every other node t ∈ {0,1}*, the labellings for its successor nodes are V(t.0) = a and V(t.1) = b. It is clear from the picture that T forms a (fully) infinite binary tree.

See also

References

- Jech, Thomas (2002). Set Theory. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-44085-2.

- Kunen, Kenneth (1980). Set Theory: An Introduction to Independence Proofs. North-Holland. ISBN 0-444-85401-0. Chapter 2, Section 5.

- Monk, J. Donald (1976). Mathematical Logic. New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 517. ISBN 0-387-90170-1.

- Hajnal, András; Hamburger, Peter (1999). Set Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521596671.

External links

- Sets, Models and Proofs by Ieke Moerdijk and Jaap van Oosten, see Definition 3.1 and Exercise 56 on pp. 68–69.

- tree (set theoretic) by Henry on PlanetMath

- branch by Henry on PlanetMath

- example of tree (set theoretic) by uzeromay on PlanetMath