Treaty of Versailles

| Treaty of Peace between the Allied and Associated Powers and Germany[1] | |

|---|---|

|

Cover of the English version | |

| Signed | 28 June 1919[2] |

| Location | Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles, Paris, France[3] |

| Effective | 10 January 1920[4] |

| Condition | Ratification by Germany and four Principal Allied Powers.[1] |

| Signatories |

Central Powers Allied Powers Other Allied Powers

|

| Depositary | French Government[5] |

| Languages | French and English[5] |

|

| |

| Paris Peace Conference |

|---|

|

Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye |

|

Neuilly-sur-Seine |

|

Treaty of Trianon |

The Treaty of Versailles (French: Traité de Versailles) was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of World War I were dealt with in separate treaties.[6] Although the armistice, signed on 11 November 1918, ended the actual fighting, it took six months of negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference to conclude the peace treaty. The treaty was registered by the Secretariat of the League of Nations on 21 October 1919, and was printed in The League of Nations Treaty Series.

Of the many provisions in the treaty, one of the most important and controversial required "Germany [to] accept the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage" during the war (the other members of the Central Powers signed treaties containing similar articles). This article, Article 231, later became known as the War Guilt clause. The treaty forced Germany to disarm, make substantial territorial concessions, and pay reparations to certain countries that had formed the Entente powers. In 1921 the total cost of these reparations was assessed at 132 billion Marks (then $31.4 billion or £6.6 billion, roughly equivalent to US $442 billion or UK £284 billion in 2015). At the time economists, notably John Maynard Keynes predicted that the treaty was too harsh—a "Carthaginian peace", and said the figure was excessive and counter-productive. The contemporary American historian Sally Marks judged the reparation figure to be lenient, a sum that was designed to look imposing but was in fact not, that had little impact on the German economy and analysed the treaty as a whole to be quite restrained and not as harsh as it could have been.[7]

The result of these competing and sometimes conflicting goals among the victors was a compromise that left none contented: Germany was neither pacified nor conciliated, nor was it permanently weakened. The problems that arose from the treaty would lead to the Locarno Treaties, which improved relations between Germany and the other European Powers, and the re-negotiation of the reparation system resulting in the Dawes Plan, the Young Plan, and the indefinite postponement of reparations at the Lausanne Conference of 1932.

Background

World War I

The First World War (1914–1918) was fought across Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Asia. Countries beyond the war zones were also affected by the disruption of international trade, finance and diplomatic pressures from the belligerents.[8] In 1917, two revolutions occurred within the Russian Empire, which led to the collapse of the Imperial Government and the rise of the Bolshevik Party led by Vladimir Lenin.[9]

Fourteen Points

On 6 April 1917, the United States entered the war against the Central Powers due to German submarine warfare against merchant ships trading with France and Britain. The American war aim was to detach the war from nationalistic disputes and ambitions after the Bolshevik disclosure of secret treaties between the Allies. The existence of these treaties tended to discredit Allied claims that Germany was the sole power with aggressive ambitions.[10]

On 8 January 1918, United States President Woodrow Wilson issued a statement that became known as the Fourteen Points. This speech outlined a policy of free trade, open agreements, democracy and self-determination. It also called for a diplomatic end to the war, international disarmament, the withdrawal of the Central Powers from occupied territories, the creation of a Polish state, the redrawing of Europe's borders along ethnic lines and the formation of a League of Nations to afford "mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike".[11][12] Wilson's speech also responded to Vladimir Lenin's Decree on Peace of November 1917, which proposed an immediate withdrawal of Russia from the war and called for a just and democratic peace uncompromised by territorial annexations. The Fourteen Points were based on the research of the Inquiry, a team of about 150 advisers led by foreign-policy advisor Edward M. House, into the topics likely to arise in the anticipated peace conference. Europeans generally welcomed Wilson's intervention, but Allied colleagues Georges Clemenceau of France, David Lloyd George of the United Kingdom and Vittorio Emanuele Orlando of Italy were sceptical of Wilsonian idealism.[13]

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, 1918

After the Central Powers launched Operation Faustschlag on the Eastern Front, the new Soviet Government of Russia signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany on 3 March 1918.[14] This treaty ended the war between Russia and the Central powers and annexed 1,300,000 square miles (3,400,000 km2) square miles of territory and 62 million people.[15] This loss equated to one third of the Russian population, 25 per cent of their territory, around a third of the country's arable land, three-quarters of its coal and iron, a third of its factories (totalling 54 per cent of the nation's industrial capacity), and a quarter of its railroads.[15][16]

Armistice

During the autumn of 1918, the Central Powers began to collapse.[17] Desertion rates within the Germany army began to increase, and civilian strikes drastically reduced war production.[18][19] On the Western Front, the Allied forces launched the Hundred Days Offensive and decisively defeated the German western armies.[20] Sailors of the Imperial German Navy at Kiel mutinied, which prompted uprisings in Germany, which became known as the German Revolution.[21][22] The German Government tried to obtain a peace settlement based on the Fourteen Points, and maintained it was on this basis that they surrendered. Following negotiations, the Allied powers and Germany signed an armistice, which came into effect on 11 November while German forces were still positioned in France and Belgium.[23][24][25]

Occupation

The terms of the armistice called for an immediate evacuation of German troops from Belgium, France, and Luxembourg within fifteen days.[26] In addition, it established that Allied forces would occupy the Rhineland. In late 1918, Allied troops entered Germany and began the occupation.[27]

Blockade

Both the German Empire and Great Britain were dependent on imports of food and raw materials, primarily from the Americas, which had to be shipped across the Atlantic Ocean. The Blockade of Germany (1914–1919) was a naval operation conducted by the Allied Powers to stop the supply of raw materials and foodstuffs reaching the Central Powers. The German Kaiserliche Marine was mainly restricted to the German Bight and used commerce raiders and unrestricted submarine warfare for a counter-blockade. The German Board of Public Health in December 1918 claimed that 763,000 German civilians had died during the Allied blockade although an academic study in 1928 put the death toll at 424,000 people.[28]

Polish uprising

In late 1918, a Polish Government was formed and an independent Poland proclaimed. In December, Poles launched an uprising within the German province of Posen. Fighting lasted until February, when an armistice was signed that left the area in Polish hands, but technically still a German possession.[29]

Negotiations

Negotiations between the Allied powers started on 18 January in the Salle de l'Horloge at the French Foreign Ministry on the Quai d'Orsay in Paris. Initially, 70 delegates from 27 nations participated in the negotiations.[30] The defeated nations of Germany, Austria, and Hungary were excluded from the negotiations. Russia was also excluded because it had negotiated a separate peace (the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk) with Germany in 1918. The terms of this treaty awarded Germany a large proportion of Russia's land and resources. Its terms were extremely harsh, as the negotiators at Versailles later pointed out.

At first a "Council of Ten" comprising two delegates each from Britain, France, the United States, Italy and Japan met officially to decide the peace terms. It became the "Big Four" when Japan dropped out and the top person from each of the other four nations met in 145 closed sessions to make all the major decisions to be ratified by the entire assembly. Apart from Italian issues, the main conditions were determined at personal meetings among the leaders of the "Big Three" nations: British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, and American President Woodrow Wilson.

The minor nations attended a weekly "Plenary Conference" that discussed issues in a general forum, but made no decisions. These members formed over 50 commissions that made various recommendations, many of which were incorporated into the final Treaty.[31][32]

French aims

As the only major allied power sharing a land border with Germany, France was chiefly concerned with weakening Germany as much as possible. The French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau described France's position best by telling Wilson: "America is far away, protected by the ocean. Not even Napoleon himself could touch England. You are both sheltered; we are not." [33] Clemenceau wished to bring the French border to the Rhine or to create a buffer state in the Rhineland, but this demand was not met by the treaty. Instead, France obtained the demilitarization of the Rhineland, a mandate over the Saar and promises of Anglo-American support in case of a new German aggression (a commitment that could not be relied on after the United States failed to ratify the treaty).[34]

British economist John Maynard Keynes argued,

So far as possible, therefore, it was the policy of France to set the clock back and undo what, since 1870, the progress of Germany had accomplished. By loss of territory and other measures her population was to be curtailed; but chiefly the economic system, upon which she depended for her new strength, the vast fabric built upon iron, coal, and transport must be destroyed. If France could seize, even in part, what Germany was compelled to drop, the inequality of strength between the two rivals for European hegemony might be remedied for generations.[35]

France, which suffered significant destruction in its northern territories (the worst damage sustained in areas that formed a so-called Red Zone) and the heaviest human losses among allies (see main article World War I casualties), was adamant on the payment of reparations. The failure of the government of the Weimar Republic to pay these reparations led to the Occupation of the Ruhr by French and Belgian forces.

British aims

Britain had suffered little land devastation during the war and Prime Minister David Lloyd George supported reparations to a lesser extent than the French. Britain began to look on a restored Germany as an important trading partner and worried about the effect of reparations on the British economy.[36]

American aims

Before the end of the war, President Woodrow Wilson put forward his Fourteen Points, which represented the liberal position at the Conference and helped shape world opinion. Wilson was concerned with rebuilding the European economy, encouraging self-determination, promoting free trade, creating appropriate mandates for former colonies, and above all, creating a powerful League of Nations that would ensure the peace. He opposed harsh treatment of Germany but was outmanoeuvered by Britain and France. He brought along top intellectuals as advisors, but his refusal to include prominent Republicans in the American delegation made his efforts seem partisan, and it contributed to a risk of political defeat at home.[37]

Treaty

_(RA)_-_The_Signing_of_Peace_in_the_Hall_of_Mirrors%2C_Versailles%2C_28th_June_1919_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

In June 1919, the Allies declared that war would resume if the German government did not sign the treaty they had agreed to among themselves. The government headed by Philipp Scheidemann was unable to agree on a common position, and Scheidemann himself resigned rather than agree to sign the treaty. Gustav Bauer, the head of the new government, sent a telegram stating his intention to sign the treaty if certain articles were withdrawn, including articles 227, 230 and 231.[nb 1] In response, the Allies issued an ultimatum stating that Germany would have to accept the treaty or face an invasion of Allied forces across the Rhine within 24 hours. On 23 June, Bauer capitulated and sent a second telegram with a confirmation that a German delegation would arrive shortly to sign the treaty.[38] On 28 June 1919, the fifth anniversary of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand (the immediate impetus for the war), the peace treaty was signed.[2] The treaty had clauses ranging from war crimes, the prohibition on the merging of Austria with Germany without the consent of the League of Nations, freedom of navigation on major European rivers, to the returning of a Koran to the king of Hedjaz.[39][40][41][42]

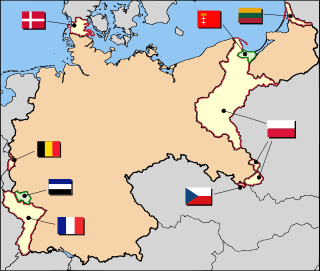

Territorial changes

The treaty stripped Germany of 25,000 square miles (65,000 km2) of territory and 7,000,000 people. It also required Germany to give up the gains made via the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and grant independence to the protectorates that had been established.[16] In Western Europe Germany was required to recognize Belgian sovereignty over Moresnet and cede control of the Eupen-Malmedy area. Within six months of the transfer, Belgium was required to conduct a plebiscite on whether the citizens of the region wanted to remain under Belgian sovereignty or return to German control, communicate the results to the League of Nations and abide by the League's decision.[43] To compensate for the destruction of French coal mines, Germany was to cede the output of the Saar coalmines to France and control of the Saar to the League of Nations for fifteen years; a plebiscite would then be held to decide sovereignty.[44] The treaty "restored" the provinces of Alsace-Lorraine to France by rescinding the treaties of Versailles and Frankfurt of 1871 as they pertained to this issue.[45] The sovereignty of Schleswig-Holstein was to be resolved by a plebiscite to be held at a future time (see Schleswig Plebiscites).[46]

In Eastern Europe, Germany was to recognize the independence of Czechoslovakia and cede parts of the province of Upper Silesia.[47] Germany had to recognize the independence of Poland and renounce "all rights and title over the territory". Portions of Upper Silesia were to be ceded to Poland, with the future of the rest of the province to be decided by plebiscite. The border would be fixed with regard to the vote and to the geographical and economic conditions of each locality.[48] The province of Posen (now Poznan), which had come under Polish control during the Greater Poland Uprising, was also to be ceded to Poland.[29][49] Pomerania, on historical and ethnic grounds, was transferred to Poland so that the new state could have access to the sea and became known as the Polish Corridor.[50] The sovereignty of part of southern East Prussia was to be decided via plebiscite while the East Prussian Soldau area, which was astride the rail line between Warsaw and Danzig, was transferred to Poland outright without plebiscite.[51][52] An area of 51,800 square kilometres (20,000 square miles) was granted to Poland at the expense of Germany.[53] Memel was to be ceded to the Allied and Associated powers, for disposal according to their wishes.[54] Germany was to cede the city of Danzig and its hinterland, including the delta of the Vistula River on the Baltic Sea, for the League of Nations to establish the Free City of Danzig.[55]

Mandates

Article 119 of the treaty required Germany to renounce sovereignty over former colonies and Article 22 converted the territories into League of Nations mandates under the control of Allied states.[56] Togoland and German Kamerun (Cameroon) were transferred to France. Ruanda and Urundi were allocated to Belgium, whereas German South-West Africa went to South Africa and the United Kingdom obtained German East Africa.[57][58][59] As compensation for the German invasion of Portuguese Africa, Portugal was granted the Kionga Triangle, a sliver of German East Africa in northern Mozambique.[60] Article 156 of the treaty transferred German concessions in Shandong, China, to Japan, not to China. Japan was granted all German possessions in the Pacific north of the equator and those south of the equator went to Australia, except for German Samoa, which was taken by New Zealand.[58][61]

Military restrictions

The treaty was comprehensive and complex in the restrictions imposed upon the post-war German armed forces (the Reichswehr). The provisions were intended to make the Reichswehr incapable of offensive action and to encourage international disarmament.[62][63] Germany was to demobilize sufficient soldiers by 31 March 1920 to leave an army of no more than 100,000 men in a maximum of seven infantry and three cavalry divisions. The treaty laid down the organisation of the divisions and support units, and the General Staff was to be dissolved.[64] Military schools for officer training were limited to three, one school per arm, and conscription was abolished. Private soldiers and Non-commissioned officers were to be retained for at least twelve years and officers for a minimum of 25 years, with former officers being forbidden to attend military exercises. To prevent Germany from building up a large cadre of trained men, the number of men allowed to leave early was limited.[65]

The number of civilian staff supporting the army was reduced and the police force was reduced to its pre-war size, with increases limited to population increases; paramilitary forces were forbidden.[66] The Rhineland was to be demilitarized, all fortifications in the Rhineland and 50 kilometres (31 miles) east of the river were to be demolished and new construction was forbidden.[67] Military structures and fortifications on the islands of Heligoland and Düne were to be destroyed.[68] Germany was prohibited from the arms trade, limits were imposed on the type and quantity of weapons and prohibited from the manufacture or stockpile of chemical weapons, armored cars, tanks and military aircraft.[69] The German navy was allowed six pre-dreadnought battleships and was limited to a maximum of six light cruisers (not exceeding 6,000 long tons (6,100 t)), twelve destroyers (not exceeding 800 long tons (810 t)) and twelve torpedo boats (not exceeding 200 long tons (200 t)) and was forbidden submarines.[70] The manpower of the navy was not to exceed 15,000 men, including manning for the fleet, coast defences, signal stations, administration, other land services, officers and men of all grades and corps. The number of officers and warrant officers was not allowed to exceed 1,500 men.[71] Germany surrendered eight battleships, eight light cruisers, forty-two destroyers, and fifty torpedo boats for decommissioning. Thirty-two auxiliary ships were to be disarmed and converted to merchant use.[72] Article 198 prohibited Germany from having an air force, including naval air forces, and required Germany to hand over all aerial related materials. In conjunction, Germany was forbidden to manufacture or import aircraft or related material for a period of six months following the signing of the treaty.[73]

Reparations

In Article 231 Germany accepted responsibility for the losses and damages caused by the war "as a consequence of the ... aggression of Germany and her allies."[74][nb 2] The following articles provided for Germany to compensate the Allied powers and to establish a "Reparation Commission" in 1921 to consider German resources and capacity to pay, give the German government an opportunity to be heard and to decide on the amount of reparations to pay. In the interim, the treaty required Germany to pay an equivalent of 20 billion gold marks ($5 billion) in gold, commodities, ships, securities or other forms. The money would also be used to pay Allied occupation costs and buy food and raw materials for Germany.[79][80]

Guarantees

To ensure compliance, the Rhineland and bridgeheads east of the Rhine were to be occupied by Allied troops for fifteen years.[81] If Germany had not committed aggression, a staged withdrawal would take place; after five years, the Cologne bridgehead and the territory north of a line along the Ruhr would be evacuated. After ten years, the bridgehead at Coblenz and the territories to the north would be evacuated and after fifteen years remaining Allied forces would be withdrawn.[82] If Germany reneged on the treaty obligations, the bridgeheads would be reoccupied immediately.[83]

International organizations

Part I of the treaty, as per all the treaties signed during the Paris Peace Conference,[nb 3] was the Covenant of the League of Nations, which provided for the creation of the League, an organization for the arbitration of international disputes.[84] Part XIII organized the establishment of the International Labour Officer, to regulate hours of work, including a maximum working day and week; the regulation of the labour supply; the prevention of unemployment; the provision of a living wage; the protection of the worker against sickness, disease and injury arising out of his employment; the protection of children, young persons and women; provision for old age and injury; protection of the interests of workers when employed abroad; recognition of the principle of freedom of association; the organization of vocational and technical education and other measures.[85] The treaty also called for the signatories to sign or ratify the International Opium Convention.[86]

Reactions

Among the allies

Britain

British officials at the conference declared French policy to be "greedy" and vindictive, with Ramsay MacDonald later announcing, after Hitler's re-militarisation of the Rhineland in 1936, that he was "pleased" that the Treaty was "vanishing", expressing his hope that the French had been taught a "severe lesson".[87]

France

France signed the Treaty and was active in the League. Clemenceau had failed to achieve all of the demands of the French people, and he was voted out of office in the elections of January 1920.

French Marshal Ferdinand Foch — who felt the restrictions on Germany were too lenient — fortuitously predicted that "this (Treaty) is not peace. It is an Armistice for twenty years."[88]

United States

After the Versailles conference Wilson claimed that "at last the world knows America as the savior of the world!"[89]

The Republican Party—led by Henry Cabot Lodge—controlled the U.S. Senate after the election of 1918, but the Senators were divided into multiple positions on the Versailles question. It proved possible to build a majority coalition, but impossible to build a two-thirds coalition that was needed to pass a treaty.[90]

An angry bloc of 12–18 "Irreconcilables", mostly Republicans but also representatives of the Irish and German Democrats, fiercely opposed the Treaty. One block of Democrats strongly supported the Versailles Treaty, even with reservations added by Lodge. A second group of Democrats supported the Treaty but followed Wilson in opposing any amendments or reservations. The largest bloc—led by Senator Lodge—[91] comprised a majority of the Republicans. They wanted a treaty with reservations, especially on Article X, which involved the power of the League of Nations to make war without a vote by the U.S. Congress.[92] All of the Irreconcilables were bitter enemies of President Wilson, and he launched a nationwide speaking tour in the summer of 1919 to refute them. However, Wilson collapsed midway with a serious stroke that effectively ruined his leadership skills.[93]

The closest the Treaty came to passage was on 19 November 1919, as Lodge and his Republicans formed a coalition with the pro-Treaty Democrats, and were close to a two-thirds majority for a Treaty with reservations, but Wilson rejected this compromise and enough Democrats followed his lead to permanently end the chances for ratification.

Among the American public as a whole, the Irish Catholics and the German Americans were intensely opposed to the Treaty, saying it favored the British.[94]

After Wilson's successor Warren G. Harding continued American opposition to the League of Nations, Congress passed the Knox–Porter Resolution bringing a formal end to hostilities between the U.S. and the Central Powers. It was signed into law by President Harding on 2 July 1921.[95][96]

The U.S.–German Peace Treaty of 1921 was signed in Berlin on 25 August 1921, the US–Austrian Peace Treaty of 1921 was signed in Vienna on 24 August 1921, and the US–Hungarian Peace Treaty of 1921 was signed in Budapest on 29 August 1921.

House's views

Wilson's former friend Edward Mandell House, present at the negotiations, wrote in his diary on 29 June 1919:

I am leaving Paris, after eight fateful months, with conflicting emotions. Looking at the conference in retrospect, there is much to approve and yet much to regret. It is easy to say what should have been done, but more difficult to have found a way of doing it. To those who are saying that the treaty is bad and should never have been made and that it will involve Europe in infinite difficulties in its enforcement, I feel like admitting it. But I would also say in reply that empires cannot be shattered, and new states raised upon their ruins without disturbance. To create new boundaries is to create new troubles. The one follows the other. While I should have preferred a different peace, I doubt very much whether it could have been made, for the ingredients required for such a peace as I would have were lacking at Paris.[97]

In Germany

On 29 April, the German delegation under the leadership of the Foreign Minister Ulrich Graf von Brockdorff-Rantzau arrived in Versailles. On 7 May, when faced with the conditions dictated by the victors, including the so-called "War Guilt Clause", von Brockdorff-Rantzau replied to Clemenceau, Wilson and Lloyd George: "We know the full brunt of hate that confronts us here. You demand from us to confess we were the only guilty party of war; such a confession in my mouth would be a lie."[98] Because Germany was not allowed to take part in the negotiations, the German government issued a protest against what it considered to be unfair demands, and a "violation of honour",[99] soon afterwards withdrawing from the proceedings of the peace conference.

Germans of all political shades denounced the treaty—particularly the provision that blamed Germany for starting the war—as an insult to the nation's honor. They referred to the treaty as "the Diktat" since its terms were presented to Germany on a take-it-or-leave-it basis. Germany′s first democratically elected head of government, Philipp Scheidemann, resigned rather than sign the treaty. In a passionate speech before the National Assembly on 21 March 1919, he called the treaty a "murderous plan" and exclaimed,

Which hand, trying to put us in chains like these, would not wither? The treaty is unacceptable.[100]

After Scheidemann′s resignation, a new coalition government was formed under Gustav Bauer. President Friedrich Ebert knew that Germany was in an impossible situation. Although he shared his countrymen's disgust with the treaty, he was sober enough to consider the possibility that the government would not be in a position to reject it. He believed that if Germany refused to sign the treaty, the Allies would invade Germany from the west--and there was no guarantee that the army would be able to make a stand in the event of an invasion. With this in mind, he asked Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg if the army was capable of any meaningful resistance in the event the Allies resumed the war. If there was even the slightest chance that the army could hold out, Ebert intended to recommend against ratifying the treaty. Hindenburg—after prodding from his chief of staff, Wilhelm Groener—concluded the army could not resume the war even on a limited scale. However, rather than inform Ebert himself, he had Groener inform the government that the army would be in an untenable position in the event of renewed hostilities. Upon receiving this, the new government recommended signing the treaty. The National Assembly voted in favour of signing the treaty by 237 to 138, with five abstentions (there were 421 delegates in total). This result was wired to Clemenceau just hours before the deadline. Foreign minister Hermann Müller and colonial minister Johannes Bell travelled to Versailles to sign the treaty on behalf of Germany. The treaty was signed on 28 June 1919 and ratified by the National Assembly on 9 July by a vote of 209 to 116.[101]

Conservatives, nationalists and ex-military leaders condemned the treaty. Politicians of the Weimar Republic who supported the treaty, socialists, communists, and Jews were viewed with suspicion as persons of questionable loyalty. It was rumored that Jews had not supported the war and had played a role in selling Germany out to its enemies. Those who seemed to benefit from a weakened Germany and the newly formed Weimar Republic were regarded as having "stabbed Germany in the back". Those who instigated unrest and strikes in the critical military industries on the home front or who opposed German nationalism were seen to have contributed to Germany's defeat. These theories were given credence by the fact that when Germany surrendered in November 1918, its armies were still on French and Belgian territory. Furthermore, on the Eastern Front, Germany had already won the war against Russia and concluded the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. In the West, Germany had seemed to have come close to winning the war with the Spring Offensive earlier in 1918. Its failure was blamed on strikes in the arms industry at a critical moment of the offensive, leaving soldiers with an inadequate supply of materiel. The strikes were regarded by nationalists as having been instigated by traitors, with the Jews taking most of the blame.

Violations

The German economy was so weak that only a small percentage of reparations was paid in hard currency. Nonetheless, even the payment of this small percentage of the original reparations (132 billion gold marks) still placed a significant burden on the German economy. Although the causes of the devastating post-war hyperinflation are complex and disputed, Germans blamed the near-collapse of their economy on the Treaty, and some economists estimated that the reparations accounted for as much as one-third of the hyper-inflation.

In March 1921, French and Belgian troops occupied Duisburg, which formed part of the demilitarized Rhineland, according to the Treaty of Versailles. In January 1923, French and Belgian forces occupied the rest of the Ruhr area as a reprisal after Germany failed to fulfill reparation payments demanded by the Versailles Treaty. The German government answered with "passive resistance", which meant that coal miners and railway workers refused to obey any instructions by the occupation forces. Production and transportation came to a standstill, but the financial consequences contributed to German hyperinflation and completely ruined public finances in Germany. Consequently, passive resistance was called off in late 1923. The end of passive resistance in the Ruhr allowed Germany to undertake a currency reform and to negotiate the Dawes Plan, which led to the withdrawal of French and Belgian troops from the Ruhr Area in 1925.

Some significant violations (or avoidances) of the provisions of the Treaty were:

- In 1919, the dissolution of the General Staff appeared to happen; however, the core of the General Staff was reestablished and hidden in the Truppenamt

- In March 1935, under the government of Adolf Hitler, Germany violated the Treaty of Versailles by introducing compulsory military conscription in Germany and rebuilding the armed forces.

- In March 1936, Germany violated the treaty by reoccupying the demilitarized zone in the Rhineland.

- In March 1938, Germany violated the treaty by annexing Austria in the Anschluss.

Historical assessments

According to David Stevenson, since the opening of French archives, most commentators have remarked on French restraint and reasonableness at the conference, though Stevenson notes that "[t]he jury is still out", and that "there have been signs that the pendulum of judgement is swinging back the other way."[102]

In his book The Economic Consequences of the Peace, John Maynard Keynes referred to the Treaty of Versailles as a "Carthaginian peace", a misguided attempt to destroy Germany on behalf of French revanchism, rather than to follow the fairer principles for a lasting peace set out in President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points, which Germany had accepted at the armistice. He stated: "I believe that the campaign for securing out of Germany the general costs of the war was one of the most serious acts of political unwisdom for which our statesmen have ever been responsible."[103] Keynes had been the principal representative of the British Treasury at the Paris Peace Conference, and used in his passionate book arguments that he and others (including some US officials) had used at Paris.[104] He believed the sums being asked of Germany in reparations were many times more than it was possible for Germany to pay, and that these would produce drastic instability.[105]

French economist Étienne Mantoux disputed that analysis. During the 1940s, Mantoux wrote a posthumously published book titled The Carthaginian Peace, or the Economic Consequences of Mr. Keynes in an attempt to rebut Keynes' claims. More recently economists have argued that the restriction of Germany to a small army saved it so much money it could afford the reparations payments.[106]

It has been argued (for instance by historian Gerhard Weinberg in his book "A World At Arms"[107]) that the treaty was in fact quite advantageous to Germany. The Bismarckian Reich was maintained as a political unit instead of being broken up, and Germany largely escaped post-war military occupation (in contrast to the situation following World War II.) In a 1995 essay, Weinberg noted that with the disappearance of Austria-Hungary and with Russia withdrawn from Europe, that Germany was now the dominant power in Eastern Europe.[108]

The British military historian Correlli Barnett claimed that the Treaty of Versailles was "extremely lenient in comparison with the peace terms that Germany herself, when she was expecting to win the war, had had in mind to impose on the Allies". Furthermore, he claimed, it was "hardly a slap on the wrist" when contrasted with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk that Germany had imposed on a defeated Russia in March 1918, which had taken away a third of Russia's population (albeit of non-Russian ethnicity), one-half of Russia's industrial undertakings and nine-tenths of Russia's coal mines, coupled with an indemnity of six billion Marks.[109] Eventually, even under the "cruel" terms of the Treaty of Versailles, Germany′s economy had been restored to its pre-war status.

Barnett also claims that, in strategic terms, Germany was in fact in a superior position following the Treaty than she had been in 1914. Germany′s eastern frontiers faced Russia and Austria, who had both in the past balanced German power. Barnett asserts that its post-war eastern borders were safer, because the former Austrian Empire fractured after the war into smaller, weaker states, Russia was wracked by revolution and civil war, and the newly restored Poland was no match for even a defeated Germany. In the West, Germany was balanced only by France and Belgium, both of which were smaller in population and less economically vibrant than Germany. Barnett concludes by saying that instead of weakening Germany, the Treaty "much enhanced" German power.[110] Britain and France should have (according to Barnett) "divided and permanently weakened" Germany by undoing Bismarck's work and partitioning Germany into smaller, weaker states so it could never have disrupted the peace of Europe again.[111] By failing to do this and therefore not solving the problem of German power and restoring the equilibrium of Europe, Britain "had failed in her main purpose in taking part in the Great War".[112]

The British historian of modern Germany, Richard J. Evans, wrote that during the war the German right was committed to an annexationist program which aimed at Germany annexing most of Europe and Africa. Consequently, any peace treaty that did not leave Germany as the conqueror would be unacceptable to them.[113] Short of allowing Germany to keep all the conquests of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Evans argued that there was nothing that could have been done to persuade the German right to accept Versailles.[113] Evans further noted that the parties of the Weimar Coalition, namely the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), the social liberal German Democratic Party (DDP) and the Christian democratic Centre Party, were all equally opposed to Versailles, and it is false to claim as some historians have that opposition to Versailles also equalled opposition to the Weimar Republic.[113] Finally, Evans argued that it is untrue that Versailles caused the premature end of the Republic, instead contending that it was the Great Depression of the early 1930s that put an end to German democracy. He also argued that Versailles was not the "main cause" of National Socialism and the German economy was "only marginally influenced by the impact of reparations".[113]

Ewa Thompson points out that the Treaty allowed numerous nations in Central and Eastern Europe to liberate themselves from oppressive German rule, a fact that is often neglected by Western historiography, more interested in understanding the German point of view. In nations that found themselves free as the result of the Treaty; such as Poles or Czechs, it is seen as symbol of recognition of wrongs committed against small nations by their much larger aggressive neighbors.[114]

Regardless of modern strategic or economic analysis, resentment caused by the treaty sowed fertile psychological ground for the eventual rise of the Nazi Party. The German historian Detlev Peukert wrote that Versailles was far from the impossible peace that most Germans claimed it was during the interwar period, and though not without flaws was actually quite reasonable to Germany.[115] Rather, Peukert argued that it was widely believed in Germany that Versailles was a totally unreasonable treaty, and it was this "perception" rather than the "reality" of the Versailles treaty that mattered.[115] Peukert noted that because of the "millenarian hopes" created in Germany during World War I when for a time it appeared that Germany was on the verge of conquering all of Europe, any peace treaty the Allies of World War I imposed on the defeated German Reich were bound to create a nationalist backlash, and there was nothing the Allies could have done to avoid that backlash.[115] Having noted that much, Peukert commented that the policy of rapprochement with the Western powers that Gustav Stresemann carried out between 1923 and 1929 were constructive policies that might have allowed Germany to play a more positive role in Europe, and that it was not true that German democracy was doomed to die in 1919 because of Versailles.[115] Finally, Peukert argued that it was the Great Depression and the turn to a nationalist policy of autarky within Germany at the same time that finished off the Weimar Republic, not the Treaty of Versailles.[115]

French historian Raymond Cartier states that millions of Germans in the Sudetenland and in Posen-West Prussia were placed under foreign rule in a hostile environment, where harassment and violation of rights by authorities are documented.[116] Cartier asserts that, out of 1,058,000 Germans in Posen-West Prussia in 1921, 758,867 fled their homelands within five years due to Polish harassment.[116] In 1926, the Polish Ministry of the Interior estimated the remaining number of Germans at fewer than 300,000. These sharpening ethnic conflicts would lead to public demands to reattach the annexed territory in 1938 and become a pretext for Hitler′s annexations of Czechoslovakia and parts of Poland.[116]

See also

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Wikisource: Treaty of Peace between Germany and the United States of America

- Septemberprogramm

- Decree on Peace

- Aftermath of World War I

- Causes of World War II

- International Opium Convention, incorporated into the Treaty of Versailles

- Little Treaty of Versailles

- Minority Treaties

- Neutrality Acts of 1930s

- Treaty of Rapallo (1920)

Notes

- Footnotes

- ↑ See the Reparations section.

- ↑ Similar wording was used in the treaties signed by the other defeated nations of the Central Powers. Article 117 of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye with Austria, Article 161 of the Treaty of Trianon with Hungary, Article 121 of the Treaty Areas of Neuilly-sur-Seine with Bulgaria and Article 231 of the Treaty of Sevres with Turkey.[75][76][77][78]

- ↑ see The Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, The Treaty of Trianon, The Treaty of Neuilly, and The Treaty of Sèvres.

- Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 Treaty of Versailles Preamble

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Slavicek, p. 114

- ↑ Slavicek, p. 107

- ↑ Boyer, p. 153

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Treaty of Versailles Signatures and Protocol

- ↑ Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919) with Austria; Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine with Bulgaria; Treaty of Trianon with Hungary; Treaty of Sèvres with the Ottoman Empire; Davis, Robert T., ed. (2010). U.S. Foreign Policy and National Security: Chronology and Index for the 20th Century 1. Santa Barbara, California: Praeger Security International. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-313-38385-4.

- ↑ Sally Marks, "The Myths of Reparations," Central European History (1978) 11#3 pp. 231-255 in JSTOR

- ↑ Simkins, Jukes, Hickey, p. 9

- ↑ Bell, p. 19

- ↑ Folly, p. xxxiv

- ↑ Tucker (2005a), p. 429

- ↑ Fourteen Points Speech

- ↑ Irwin Unger, These United States (2007) 561.

- ↑ Simkins, Jukes, Hickey, p. 265

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Tucker (2005a), p. 225

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Truitt, p. 114

- ↑ Beller, pp. 182-95

- ↑ Bessel, pp.47–8

- ↑ Hardach, pp. 183–4

- ↑ Simkins, p. 71

- ↑ Tucker (2005a), p. 638

- ↑ Schmitt, p. 101

- ↑ Schmitt, p. 102

- ↑ Weinberg, p. 8

- ↑ Boyer, p. 526

- ↑ Edmonds, (1943), p. 1

- ↑ Martel (1999), p. 18

- ↑ Grebler, Leo (1940). The Cost of the World War to Germany and Austria-Hungary. Yale University Press. 1940 Page78

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Frucht, p. 24

- ↑ Lentin, Antony (1985) [1984]. Guilt at Versailles: Lloyd George and the Pre-history of Appeasement. Routledge. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-416-41130-0.

- ↑ Slavicek, pp. 40-1

- ↑ Venzon, p. 439

- ↑ Keylor, William R. (1998). The Legacy of the Great War: Peacemaking, 1919. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin. p. 34. ISBN 0-669-41711-4.

- ↑ Larousse

- ↑ John Maynard Keynes, The Economic Consequences of the Peace (Harcourt Brace and Howe, 1920) p. 34

- ↑ David Thomson, Europe Since Napoleon. Penguin Books. 1970, p. 605.

- ↑ John Milton Cooper, Woodrow Wilson: A Biography (2011) pp 454-505

- ↑ Slavicek, p. 73

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, articles 227-230

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Article 80

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Part XII

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Article 246

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, articles 33 and 34

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, articles 45 and 49

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Section V preamble and Article 51

- ↑ Peckham, p. 107

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, articles 81 and 83

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Article 88 and annex

- ↑ Martin, p. lii

- ↑ Boemeke, p. 325

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Article 94

- ↑ Ingrao, p. 261

- ↑ Brezina, p. 34

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Article 99

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, articles 100-4

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, articles 22 and 119

- ↑ Tucker (2005a), p. 437

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Benians, p. 658

- ↑ Tucker (2005a), p. 1224

- ↑ Roberts, p. 496

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Article 156

- ↑ Shuster, p. 74

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Part V preamble

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, articles 159, 160, 163 and Table 1

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, articles 173, 174, 175 and 176

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, articles 161, 162, and 176

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, articles 42, 43, and 180

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Article 115

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, articles 165, 170, 171, 172, 198 and tables No. II and III.

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, articles 181 and 190

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Article 183

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, articles 185 and 187

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, articles 198, 201, and 202

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Article 231

- ↑ Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Article 177

- ↑ Treaty of Trianon, Article 161

- ↑ Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine, Article 121

- ↑ Treaty of Sèvres, Article 231

- ↑ Martel (2010), p. 156

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, articles 232-5

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Article 428

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Article 429

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Article 430

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Part I

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Part XIII preamble and Article 388

- ↑ Treaty of Versailles, Article 295

- ↑ Stevenson 1998, p. 10.

- ↑ R. Henig, Versailles and After: 1919–1933 (London: Routledge, 1995) p. 52.

- ↑ President Woodrow Wilson speaking on the League of Nations to a luncheon audience in Portland OR. 66th Cong., 1st sess. Senate Documents: Addresses of President Wilson (May–November 1919), vol.11, no. 120, p.206.

- ↑ Thomas A. Bailey, Woodrow Wilson and the Great Betrayal (1945)

- ↑ William C. Widenor, Henry Cabot Lodge and the Search for an American Foreign Policy (1980)

- ↑ Ralph A. Stone, The Irreconcilables: The Fight Against the League of Nations (1970)

- ↑ John Milton Cooper, Jr. Woodrow Wilson: A Biography (2009) ch 22-23

- ↑ Duff, John B. (1968). "The Versailles Treaty and the Irish-Americans". Journal of American History 55 (3): 582–598. doi:10.2307/1891015. JSTOR 1891015.

- ↑ Wimer, Kurt; Wimer, Sarah (1967). "The Harding Administration, the League of Nations, and the Separate Peace Treaty". The Review of Politics (Cambridge University Press) 29 (1): 13–24. doi:10.1017/S0034670500023706. JSTOR 1405810.

- ↑ Staff (3 July 1921). "HARDING ENDS WAR; SIGNS PEACE DECREE AT SENATOR'S HOME. Thirty Persons Witness Momentous Act in Frelinghuysen Living Room at Raritan.". The New York Times.

- ↑ Bibliographical Introduction to "Diary, Reminiscences and Memories of Colonel Edward M. House".

- ↑ Foreign Minister Brockdorff-Ranzau when faced with the conditions on 7 May: "Wir kennen die Wucht des Hasses, die uns hier entgegentritt. Es wird von uns verlangt, daß wir uns als die allein Schuldigen am Krieg bekennen; ein solches Bekenntnis wäre in meinem Munde eine Lüge". 2008 School Projekt Heinrich-Heine-Gesamtschule, Düsseldorf http://www.fkoester.de/kursbuch/unterrichtsmaterial/13_2_74.html

- ↑ 2008 School Projekt Heinrich-Heine-Gesamtschule, Düsseldorf http://www.fkoester.de/kursbuch/unterrichtsmaterial/13_2_74.html

- ↑ Lauteinann, Geschichten in Quellen Bd. 6, S. 129.

- ↑ Koppel S. Pinson (1964). Modern Germany: Its History and Civilization (13th printing ed.). New York: Macmillan. p. 397 f. ISBN 0-88133-434-0.

- ↑ Stevenson 1998, p. 11.

- ↑ John Maynard Keynes. The Economic Consequences of the Peace at Project Gutenberg

- ↑ Markwell, Donald (2006). John Maynard Keynes and International Relations: Economic Paths to War and Peace. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Keynes (1919). The Economic Consequences of the Peace. Ch VI.

The Treaty includes no provisions for the economic rehabilitation of Europe—nothing to make the defeated Central Empires into good neighbours, nothing to stabilize the new States of Europe, nothing to reclaim Russia; nor does it promote in any way a compact of economic solidarity amongst the Allies themselves; no arrangement was reached at Paris for restoring the disordered finances of France and Italy, or to adjust the systems of the Old World and the New. The Council of Four paid no attention to these issues, being preoccupied with others—Clemenceau to crush the economic life of his enemy, Lloyd George to do a deal and bring home something which would pass muster for a week, the President to do nothing that was not just and right. It is an extraordinary fact that the fundamental economic problems of a Europe starving and disintegrating before their eyes, was the one question in which it was impossible to arouse the interest of the Four. Reparation was their main excursion into the economic field, and they settled it as a problem of theology, of polities, of electoral chicane, from every point of view except that of the economic future of the States whose destiny they were handling.

- ↑ Hantke, Max; Spoerer, Mark (2010). "The imposed gift of Versailles: the fiscal effects of restricting the size of Germany's armed forces, 1924–9" (PDF). Economic History Review 63 (4): 849–864. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2009.00512.x.

- ↑ Reynolds, David. (20 February 1994). "Over There, and There, and There." Review of: "A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II," by Gerhard L. Weinberg. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Weinberg, Gerhard Germany, Hitler and World War II, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995 page 16.

- ↑ Correlli Barnett, The Collapse of British Power (London: Pan, 2002), p. 392.

- ↑ Barnett, p. 316.

- ↑ Barnett, p. 318.

- ↑ Barnett, p. 319.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 113.2 113.3 Evans, Richard In Hitler's Shadow, New York: Panatheon 1989 page 107.

- ↑ The Surrogate Hegemon in Polish Postcolonial Discourse Ewa Thompson, Rice University

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 115.2 115.3 115.4 Peukert, Detlev The Weimar Republic, New York: Hill & Wang, 1992 page 278.

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 116.2 La Seconde Guerre mondiale, Raymond Cartier, Paris, Larousse Paris Match, 1965, quoted in: Pater Lothar Groppe (2004-08-28). "Die "Jagd auf Deutsche" im Osten: Die Verfolgung begann nicht erst mit dem "Bromberger Blutsonntag" vor 50 Jahren". Preußische Allgemeine Zeitung / 28. August 2004 (in German). Retrieved 2010-09-22.

'Von 1.058.000 Deutschen, die noch 1921 in Posen und Westpreußen lebten', ist bei Cartier zu lesen, 'waren bis 1926 unter polnischem Druck 758.867 abgewandert. Nach weiterer Drangsal wurde das volksdeutsche Bevölkerungselement vom Warschauer Innenministerium am 15. Juli 1939 auf weniger als 300.000 Menschen geschätzt.'

References

- Andelman, David A. (2008). A Shattered Peace: Versailles 1919 and the Price We Pay Today. New York/London: J. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-78898-0.

- Bell, Origins of the Second World War

- Cooper, John Milton. Breaking the Heart of the World: Woodrow Wilson and the Fight for the League of Nations (2010) excerpt and text search

- Demarco, Neil (1987). The World This Century. London: Collins Educational. ISBN 0-00-322217-9.

- Herron, George D. (1924). The Defeat in the Victory. Boston: Christopher Publishing House. xvi, [4], 202 p.

- Macmillan, Margaret (2001). Peacemakers. London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-5939-1.

Also published as Macmillan, Margaret (2001). Paris 1919: Six Months that Changed the World. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-375-76052-0.

- Markwell, Donald (2006). John Maynard Keynes and International Relations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-829236-8.

- Martel, Origins of the Second World War Reconsidered

- Sharp, Alan (2011). Consequences of Peace: The Versailles Settlement: Aftermath and Legacy 1919-2010. Haus Publishing.

- Sharp, Alan. The Versailles Settlement: Peacemaking After the First World War, 1919-1923 (2008)

- Stevenson, David (1998). "France at the Paris Peace Conference: Addressing the Dilemmas of Security". In Robert W. D. Boyce. French Foreign and Defence Policy, 1918–1940: The Decline and Fall of a Great Power. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-15039-2.

- Wheeler-Bennett, Sir John (1972). The Wreck of Reparations, being the political background of the Lausanne Agreement, 1932. New York: H. Fertig.

Further reading

- Manfred F. Boemke, Gerald D. Feldman, and Elisabeth Gläser (eds.), The Treaty of Versailles: A Reassessment After 75 Years. Washington, DC: German Historical Institute, 1998.

- Norman A. Graebner and Edward M. Bennett, The Versailles Treaty and Its Legacy: The Failure of the Wilsonian Vision. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Treaty of Versailles. |

- Photographs of the document

- The consequences of the Treaty of Versailles for today's world

- Text of Protest by Germany and Acceptance of Fair Peace Treaty

- Woodrow Wilson Original Letters on Treaty of Versailles Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- My 1919—A film from the Chinese point of view, the only country that did not sign the treaty

- "Versailles Revisted" (Review of Manfred Boemeke, Gerald Feldman and Elisabeth Glaser, The Treaty of Versailles: A Reassessment after 75 Years. Cambridge, UK: German History Institute, Washington, and Cambridge University Press, 1998), Strategic Studies 9:2 (Spring 2000), 191–205

- Map of Europe and the impact of the Versailles Treaty at omniatlas.com

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||