Transcranial magnetic stimulation

| Transcranial magnetic stimulation | |

|---|---|

| Intervention | |

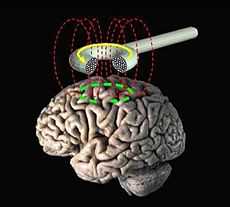

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (schematic diagram) | |

| MeSH | D050781 |

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a noninvasive method used to stimulate small regions of the brain. During a TMS procedure, a magnetic field generator, or "coil" is placed near the head of the person receiving the treatment.[1]:3 The coil produces small electrical currents in the region of the brain just under the coil via electromagnetic induction. The coil is connected to a pulse generator, or stimulator, that delivers electrical current to the coil.[2]

TMS is used diagnostically to measure the connection between the brain and a muscle to evaluate damage from stroke, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, movement disorders, motor neuron disease and injuries and other disorders affecting the facial and other cranial nerves and the spinal cord.[3]

The use of single-pulse TMS was approved by the FDA for use in migraine[4] and repetitive TMS (rTMS) for use in treatment-resistant major depressive disorder.[5] Evidence suggests it is useful for neuropathic pain[6] and treatment-resistant major depressive disorder.[6][7] Evidence also suggests that TMS may be useful for negative symptoms of schizophrenia and loss of function caused by stroke.[6] As of 2014, all other investigated uses of rTMS have only possible or no clinical efficacy.[6]

Matching the discomfort of TMS to distinguish true effects from placebo is an important and challenging issue that influences the results of clinical trials.[6][8][9] The greatest risks of TMS are the rare occurrence of syncope (fainting) and even less commonly, induced seizures.[8] Other adverse effects of TMS include discomfort or pain, transient induction of hypomania, transient cognitive changes, transient hearing loss, transient impairment of working memory, and induced currents in electrical circuits in implanted devices.[8]

Medical uses

The use of TMS can be divided into diagnostic and therapeutic uses.

Diagnosis

TMS can be used clinically to measure activity and function of specific brain circuits in humans.[3] The most robust and widely accepted use is in measuring the connection between the primary motor cortex and a muscle to evaluate damage from stroke, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, movement disorders, motor neuron disease and injuries and other disorders affecting the facial and other cranial nerves and the spinal cord.[3][10][11][12] TMS has been suggested as a means of assessing short-interval intracortical inhibition (SICI) which measures the internal pathways of the motor cortex but this use has not yet been validated.[13]

Treatment

For neuropathic pain, a condition for which evidence-based medicine fails to treat a significant number of people with the condition, high-frequency (HF) repetitive TMS (rTMS) of the brain region corresponding to the part of the body in pain, appears effective.[6]

For treatment-resistant major depressive disorder, HF-rTMS of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) appears effective and low-frequency (LF) rTMS of the right DLPFC has probable efficacy.[6][7] The Royal Australia and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists has endorsed rTMS for trMDD.[14][15]

For negative symptoms of schizophrenia, HF-rTMS of the left DLPFC has probable efficacy.[6]

For loss of function caused by stroke LF-rTMS of the corresponding brain region has probable efficacy.[6]

Many other potential uses have only demonstrated weak or negligible efficacy. TMS has failed to show effectiveness for the treatment of brain death, coma, and other persistent vegetative states.[6] As of 2014 there was insufficient evidence to determine the safety and efficacy of TMS in panic disorder.[16]

Adverse effects

Although TMS is generally regarded as safe, risks increase for therapeutic rTMS compared to single or paired TMS for diagnostic purposes. In the field of therapeutic TMS, risks increase with higher frequencies.[8]

The greatest risk is the rare occurrence of syncope (fainting) and even less commonly, induced seizures.[8][17]

Other adverse effects of TMS include discomfort or pain, transient induction of hypomania, transient cognitive changes, transient hearing loss, transient impairment of working memory, and induced currents in electrical circuits in implanted devices.[8]

Devices and procedure

During a transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) procedure, a magnetic field generator, or "coil" is placed near the head of the person receiving the treatment.[1]:3 The coil produces small electrical currents in the region of the brain just under the coil via electromagnetic induction. The coil is positioned by finding anatomical landmarks on the skull including, but not limited to, the inion or the nasion.[18] The coil is connected to a pulse generator, or stimulator, that delivers electrical current to the coil.[2]

Society and culture

Regulatory approvals

Navigated TMS

Nexstim obtained 510(k) FDA clearance of Navigated Brain Stimulation for the assessment of the primary motor cortex for pre-procedural planning in December 2009.[19]

Nexstim obtained FDA 510K clearance for NexSpeech navigated brain stimulation device for neurosurgical planning in June 2011.[20]

Depression

Neuronetics obtained FDA 510K clearance to market its NeuroStar System for use in adults with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (December 2008).[5]

Migraine

eNeura Therapeutics obtained classification of Cenera System for use to treat migraine headache as a Class II medical device under the "de novo pathway"[21] in December 2013.[4]

Health insurance considerations

United States

Commercial health insurance

In 2013, several commercial health insurance plans in the United States, including Anthem, Health Net, and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Nebraska and of Rhode Island, covered TMS for the treatment of depression for the first time.[22] In contrast, UnitedHealthcare issued a medical policy for TMS in 2013 that stated there is insufficient evidence that the procedure is beneficial for health outcomes in patients with depression. UnitedHealthcare noted that methodological concerns raised about the scientific evidence studying TMS for depression include small sample size, lack of a validated sham comparison in randomized controlled studies, and variable uses of outcome measures.[23] Other commercial insurance plans whose 2013 medical coverage policies stated that the role of TMS in the treatment of depression and other disorders had not been clearly established or remained investigational included Aetna, Cigna and Regence.[24]

Medicare

Policies for Medicare coverage vary among local jurisdictions within the Medicare system,[25] and Medicare coverage for TMS has varied among jurisdictions and with time. For example:

- In early 2012 in New England, Medicare covered TMS for the first time in the United States.[26] However, that jurisdiction later decided to end coverage after October, 2013.[27]

- In August 2012, the jurisdiction covering Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Colorado, Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico determined that there was insufficient evidence to cover the treatment,[28] but the same jurisdiction subsequently determined that Medicare would cover TMS for the treatment of depression after December 2013.[29]

United Kingdom's National Health Service

The United Kingdom's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) issues guidance to the National Health Service (NHS) in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. NICE guidance does not cover whether or not the NHS should fund a procedure. Local NHS bodies (primary care trusts and hospital trusts) make decisions about funding after considering the clinical effectiveness of the procedure and whether the procedure represents value for money for the NHS.[30]

NICE evaluated TMS for severe depression (IPG 242) in 2007, and subsequently considered TMS for reassessment in January 2011 but did not change its evaluation.[31] The Institute found that TMS is safe, but there is insufficient evidence for its efficacy.[31]

In January 2014, NICE reported the results of an evaluation of TMS for treating and preventing migraine (IPG 477). NICE found that short-term TMS is safe but there is insufficient evidence to evaluate safety for long-term and frequent uses. It found that evidence on the efficacy of TMS for the treatment of migraine is limited in quantity, that evidence for the prevention of migraine is limited in both quality and quantity.[32]

Technical information

TMS uses electromagnetic induction to generate an electric current across the scalp and skull without physical contact. A plastic-enclosed coil of wire is held next to the skull and when activated, produces a magnetic field oriented orthogonal to the plane of the coil. The magnetic field passes unimpeded through the skin and skull, inducing an oppositely directed current in the brain that activates nearby nerve cells in much the same way as currents applied directly to the cortical surface.[33]

The path of this current is difficult to model because the brain is irregularly shaped and electricity and magnetism are not conducted uniformly throughout its tissues. The magnetic field is about the same strength as an MRI, and the pulse generally reaches no more than 5 centimeters into the brain unless using the deep transcranial magnetic stimulation variant of TMS.[34] Deep TMS can reach up to 6 cm into the brain to stimulate deeper layers of the motor cortex, such as that which controls leg motion.[35]

Mechanism of action

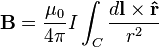

From the Biot–Savart law

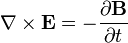

it has been shown that a current through a wire generates a magnetic field around that wire. Transcranial magnetic stimulation is achieved by quickly discharging current from a large capacitor into a coil to produce pulsed magnetic fields of 1-10 mT.[36] By directing the magnetic field pulse at a targeted area of the brain, one can either depolarize or hyperpolarize neurons in the brain. The magnetic flux density pulse generated by the current pulse through the coil causes an electric field as explained by the Maxwell-Faraday equation,

.

.This electric field causes a change in the transmembrane current of the neuron, which leads to the depolarization or hyperpolarization of the neuron and the firing of an action potential.[36]

The exact details of how TMS functions are still being explored. The effects of TMS can be divided into two types depending on the mode of stimulation:

- Single or paired pulse TMS causes neurons in the neocortex under the site of stimulation to depolarize and discharge an action potential. If used in the primary motor cortex, it produces muscle activity referred to as a motor evoked potential (MEP) which can be recorded on electromyography. If used on the occipital cortex, 'phosphenes' (flashes of light) might be perceived by the subject. In most other areas of the cortex, the participant does not consciously experience any effect, but his or her behaviour may be slightly altered (e.g., slower reaction time on a cognitive task), or changes in brain activity may be detected using sensing equipment.[37]

- Repetitive TMS produces longer-lasting effects which persist past the initial period of stimulation. rTMS can increase or decrease the excitability of the corticospinal tract depending on the intensity of stimulation, coil orientation, and frequency. The mechanism of these effects is not clear, though it is widely believed to reflect changes in synaptic efficacy akin to long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD).[38]

MRI images, recorded during TMS of the motor cortex of the brain, have been found to match very closely with PET produced by voluntary movements of the hand muscles innervated by TMS, to 5–22 mm of accuracy.[39] The localisation of motor areas with TMS has also been seen to correlate closely to MEG[40] and also fMRI.[41]

Coil types

The design of transcranial magnetic stimulation coils used in either treatment or diagnostic/experimental studies may differ in a variety of ways. These differences should be considered in the interpretation of any study result, and the type of coil used should be specified in the study methods for any published reports.

The most important considerations include:

- the type of material used to construct the core of the coil

- the geometry of the coil configuration

- the biophysical characteristics of the pulse produced by the coil.

With regard to coil composition, the core material may be either a magnetically inert substrate (i.e., the so-called ‘air-core’ coil design), or possess a solid, ferromagnetically active material (i.e., the so-called ‘solid-core’ design). Solid core coil design result in a more efficient transfer of electrical energy into a magnetic field, with a substantially reduced amount of energy dissipated as heat, and so can be operated under more aggressive duty cycles often mandated in therapeutic protocols, without treatment interruption due to heat accumulation, or the use of an accessory method of cooling the coil during operation. Varying the geometric shape of the coil itself may also result in variations in the focality, shape, and depth of cortical penetration of the magnetic field. Differences in the coil substance as well as the electronic operation of the power supply to the coil may also result in variations in the biophysical characteristics of the resulting magnetic pulse (e.g., width or duration of the magnetic field pulse). All of these features should be considered when comparing results obtained from different studies, with respect to both safety and efficacy.[42]

A number of different types of coils exist, each of which produce different magnetic field patterns. Some examples:

- round coil: the original type of TMS coil

- figure-eight coil (i.e., butterfly coil): results in a more focal pattern of activation

- double-cone coil: conforms to shape of head, useful for deeper stimulation

- four-leaf coil: for focal stimulation of peripheral nerves[43]

- H-coil: for deep transcranial magnetic stimulation

Design variations in the shape of the TMS coils allow much deeper penetration of the brain than the standard depth of 1.5-2.5 cm. Circular crown coils, Hesed (or H-core) coils, double cone coils, and other experimental variations can induce excitation or inhibition of neurons deeper in the brain including activation of motor neurons for the cerebellum, legs and pelvic floor. Though able to penetrate deeper in the brain, they are less able to produce a focused, localized response and are relatively non-focal.[8]

History

Early attempts at stimulation of the brain using a magnetic field included those, in 1910, of Silvanus P. Thompson in London.[44] The principle of inductive brain stimulation with eddy currents has been noted since the 20th century. The first successful TMS study was performed in 1985 by Anthony Barker and his colleagues at the Royal Hallamshire Hospital in Sheffield, England.[45] Its earliest application demonstrated conduction of nerve impulses from the motor cortex to the spinal cord, stimulating muscle contractions in the hand. As compared to the previous method of transcranial stimulation proposed by Merton and Morton in 1980[46] in which direct electrical current was applied to the scalp, the use of electromagnets greatly reduced the discomfort of the procedure, and allowed mapping of the cerebral cortex and its connections.

Research

Areas of research include the rehabilitation of aphasia and motor disability after stroke,[11][12][6][8][47] tinnitus,[6][48] anxiety disorders,[6] obsessive-compulsive disorder,[6] amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,[6] multiple sclerosis,[6] epilepsy,[6] Alzheimer's disease,[6] Parkinson's disease,[49]schizophrenia,[6] substance abuse,[6] addiction,[6][50] and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[6][51]

Study blinding

It is difficult to establish a convincing form of "sham" TMS to test for placebo effects during controlled trials in conscious individuals, due to the neck pain, headache and twitching in the scalp or upper face associated with the intervention.[6][8] "Sham" TMS manipulations can affect cerebral glucose metabolism and MEPs, which may confound results.[52] This problem is exacerbated when using subjective measures of improvement.[8] Placebo responses in trials of rTMS in major depression are negatively associated with refractoriness to treatment, vary among studies and can influence results.[53]

A 2011 review found that only 13.5% of 96 randomized control studies of rTMS to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex had reported blinding success and that, in those studies, people in real rTMS groups were significantly more likely to think that they had received real TMS, compared with those in sham rTMS groups.[54] Depending on the research question asked and the experimental design, matching the discomfort of rTMS to distinguish true effects from placebo can be an important and challenging issue.[6][8][9]

See also

- Cranial electrotherapy stimulation

- Electrical brain stimulation

- Transcranial direct current stimulation

- Electroconvulsive therapy

- Cortical stimulation mapping

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 NiCE. January 2014 Transcranial magnetic stimulation for treating and preventing migraine

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Michael Craig Miller for Harvard Health Publications. July 26, 2012 Magnetic stimulation: a new approach to treating depression?

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Groppa, S.; Oliviero, A.; Eisen, A.; Quartarone, A.; Cohen, L. G.; Mall, V.; Kaelin-Lang, A.; Mima, T.; Rossi, S.; Thickbroom, G. W.; Rossini, P. M.; Ziemann, U.; Valls-Solé, J.; Siebner, H. R. (2012). "A practical guide to diagnostic transcranial magnetic stimulation: Report of an IFCN committee". Clinical Neurophysiology 123 (5): 858–882. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2012.01.010. PMID 22349304.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 FDA 13 December 2013 FDA letter to eNeura re de novo classification review

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Melkerson, MN (2008-12-16). "Special Premarket 510(k) Notification for NeuroStar® TMS Therapy System for Major Depressive Disorder" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 6.20 6.21 6.22 6.23 Lefaucheur, JP et al. (2014). "Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS)". Clinical Neurophysiology 125 (11): 2150–2206. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2014.05.021. PMID 25034472.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 George, MS; Post, RM (2011). "Daily Left Prefrontal Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Acute Treatment of Medication-Resistant Depression". American Journal of Psychiatry 168 (4): 356–364. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10060864. PMID 21474597.

(6) Gaynes BN, Lux L, Lloyd S, Hansen RA, Gartlehner G, Thieda P, Brode S, Swinson Evans T, Jonas D, Crotty K, Viswanathan M, Lohr KN, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina (September 2011). "Nonpharmacologic Interventions for Treatment-Resistant Depression in Adults. Comparative Effectiveness Review Number 33. (Prepared by RTI International-University of North Carolina (RTI-UNC) Evidence-based Practice Center)". AHRQ Publication No. 11-EHC056-EF. Rockville, Maryland: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. p. 36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-11. Retrieved 2011-10-11. - ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 8.9 8.10 Rossi S et al. (Dec 2009). "Safety, ethical considerations, and application guidelines for the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice and research". Clin Neurophysiol 120 (12): 2008–39. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2009.08.016. PMC 3260536. PMID 19833552.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Duecker, F.; Sack, A. T. (2015). "Rethinking the role of sham TMS". Frontiers in Psychology 6. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00210. PMID 25767458.

- ↑ Rossini, P; Rossi, S (2007). "Transcranial magnetic stimulation: diagnostic, therapeutic, and research potential". Neurology 68 (7): 484–488. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000250268.13789.b2. PMID 17296913.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Dimyan, MA; Cohen, LG (2009). "Contribution of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation to the Understanding of Functional Recovery Mechanisms After Stroke". Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair 24 (2): 125–135. doi:10.1177/1545968309345270. PMC 2945387. PMID 19767591.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Nowak, D; Bösl, K; Podubeckà, J; Carey, J (2010). "Noninvasive brain stimulation and motor recovery after stroke". Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience 28 (4): 531–544. doi:10.3233/RNN-2010-0552. PMID 20714076.

- ↑ Kujirai, T.; Caramia, M. D.; Rothwell, J. C.; Day, B. L.; Thompson, P. D.; Ferbert, A.; Wroe, S.; Asselman, P.; Marsden, C. D. (1993). "Corticocortical inhibition in human motor cortex". The Journal of physiology 471: 501–519. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019912. PMC 1143973. PMID 8120818.

- ↑ The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. (2013) Position Statement 79. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. Practice and Partnerships Committee

- ↑ Bersani FS et al. (Jan 2013). "Deep transcranial magnetic stimulation as a treatment for psychiatric disorders: a comprehensive review". Eur Psychiatry 28 (1): 30–9. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2012.02.006. PMID 22559998.

- ↑ Li, H; Wang, J; Li, C; Xiao, Z (Sep 17, 2014). "Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for panic disorder in adults.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 9: CD009083. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009083.pub2. PMID 25230088.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, PB; Daskalakis, ZJ (2013). "7. rTMS-Associated Adverse Events". Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Depressive Disorders. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. pp. 81–90. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-36467-9. ISBN 978-3-642-36466-2. At Google Books.

- ↑ Nauczyciel, C; Hellier, P; Morandi, X; Blestel, S; Drapier, D; Ferre, JC; Barillot, C; Millet, B (30 April 2011). "Assessment of standard coil positioning in transcranial magnetic stimulation in depression". Psychiatry Research 186 (2-3): 232–8. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2010.06.012. PMID 20692709.

- ↑ http://www.nexstim.com/news-and-events/press-releases/press-releases-archive/fda-clears-nexstim-s-navigated-brain-stimulation-for-non-invasive-cortical-mapping-prior-to-neurosurgery/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20120611005730/en/Nexstim-Announces-FDA-Clearance-NexSpeech%C2%AE-%E2%80%93-Enabling#.VGm4MGNjmnw/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Michael Drues, for Med Device Online. 5 February 2014 Secrets Of The De Novo Pathway, Part 1: Why Aren't More Device Makers Using It?

- ↑ (1) Anthem (2013-04-16). "Medical Policy: Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Depression and Other Neuropsychiatric Disorders". Policy No. BEH.00002. Anthem. Archived from the original on 2013-12-11. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

(2) Health Net (March 2012). "National Medical Policy: Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation". Policy Number NMP 508. Health Net. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-11. Retrieved 2012-09-05.

(3) Blue Cross Blue Shield of Nebraska (2011-05-2011). "Medical Policy Manual". Section IV.67. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Nebraska. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-11. Check date values in:|date=, |year= / |date= mismatch(help)

(4) Blue Cross Blue Shield of Rhode Island (2012-05-15). "Medical Coverage Policy: Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Treatment of Depression and Other Psychiatric/Neurologic Disorders". Blue Cross Blue Shield of Rhode Island. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-11. Retrieved 2012-09-05. - ↑ UnitedHealthcare (2013-12-01). "Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation". UnitedHealthCare. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-11. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

- ↑ (1) Aetna (2013-10-11). "Clinical Policy Bulletin: Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation and Cranial Electrical Stimulation". Number 0469. Aetna. Archived from the original on 2013-12-11. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

(2) Cigna (2013-01-15). "Cigna Medical Coverage Policy: Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation". Coverage Policy Number 0383. Cigna. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-11. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

(3) Regence (2013-06-01). "Medical Policy: Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation as a Treatment of Depression and Other Disorders". Policy No. 17. Regence. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-11. Retrieved 2013-12-11. - ↑ "Medicare Administrative Contractors". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2013-07-10. Archived from the original on 2014-02-17. Retrieved 2014-02-14.

- ↑ (1) NHIC, Corp. (2013-10-24). "Local Coverage Determination (LCD) for Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) (L32228)". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved 2014-02-17.

(2) "Important Treatment Option for Depression Receives Medicare Coverage". Press Release. PBN.com: Providence Business News. 2012-03-30. Archived from the original on 2012-10-11. Retrieved 2012-10-11.

(3) The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (June 2012). "Coverage Policy Analysis: Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS)". The New England Comparative Effectiveness Public Advisory Council (CEPAC). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-11. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

(4) "Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Cites Influence of New England Comparative Effectiveness Public Advisory Council (CEPAC)". Berlin, Vermont: Central Vermont Medical Center. 2012-02-06. Archived from the original on 2012-10-12. Retrieved 2012-10-12. - ↑ National Government Services, Inc. (2013-10-25). "Local Coverage Determination (LCD): Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (L32038)". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved 2014-02-17.

- ↑ Novitas Solutions, Inc. (2013-12-04). "LCD L32752 - Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Depression". Contractor's Determination Number L32752. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved 2014-02-17.

- ↑ Novitas Solutions, Inc. (2013-12-05). "LCD L33660 - Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) for the Treatment of Depression". Contractor's Determination Number L33660. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved 2014-02-17.

- ↑ NICE About NICE: What we do

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "Transcranial magnetic stimulation for severe depression (IPG242)". London, England: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 2011-03-04.

- ↑ "Transcranial magnetic stimulation for treating and preventing migraine". London, England: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. January 2014.

- ↑ Cacioppo, JT; Tassinary, LG; Berntson, GG., ed. (2007). Handbook of psychophysiology (3rd ed.). New York: Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 121. ISBN 0-521-84471-1.

- ↑ "Brain Stimulation Therapies". National Institute of Mental Health. 2009-11-17. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ (1) Zangen, A.; Roth, Y.; Voller, B.; Hallett, M. (2005). "Transcranial magnetic stimulation of deep brain regions: Evidence for efficacy of the H-Coil". Clinical Neurophysiology 116 (4): 775–779. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2004.11.008. PMID 15792886.

(2) Huang, YZ; Sommer, M; Thickbroom, G; Hamada, M; Pascual-Leonne, A; Paulus, W; Classen, J; Peterchev, AV; Zangen, A; Ugawa, Y (2009). "Consensus: New methodologies for brain stimulation". Brain Stimulation 2 (1): 2–13. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2008.09.007. PMID 20633398. - ↑ 36.0 36.1 V. Walsh and A. Pascual-Leone, "Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation: A Neurochronometrics of Mind." Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2003.

- ↑ Pascual-Leone A; Davey N; Rothwell J; Wassermann EM; Puri BK (2002). Handbook of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 0-340-72009-3.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, P; Fountain, S; Daskalakis, Z (2006). "A comprehensive review of the effects of rTMS on motor cortical excitability and inhibition". Clinical Neurophysiology 117 (12): 2584–2596. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2006.06.712. PMID 16890483.

- ↑ Wassermann, EM; Wang, B; Zeffiro, TA; Sadato, N; Pascual-Leone, A; Toro, C; Hallett, M (1996). "Locating the Motor Cortex on the MRI with Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation and PET". NeuroImage 3 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1006/nimg.1996.0001. PMID 9345470.

- ↑ T. Morioka, T. Yamamoto, A. Mizushima, S. Tombimatsu, H. Shigeto, K. Hasuo, S. Nishio, K. Fujii and M. Fukui. Comparison of magnetoencephalography, functional MRI, and motor evoked potentials in the localization of the sensory-motor cortex. Neurol. Res., vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 361-367. 1995

- ↑ Terao, Y; Ugawa, Y; Sakai, K; Miyauchi, S; Fukuda, H; Sasaki, Y; Takino, R; Hanajima, R; Furubayashi, T; püTz, B; Kanazawa, I (1998). "Localizing the site of magnetic brain stimulation by functional MRI". Experimental Brain Research 121 (2): 145. doi:10.1007/s002210050446.

- ↑ Riehl M (2008). "TMS Stimulator Design". In Wassermann EM, Epstein CM, Ziemann U, Walsh V, Paus T, Lisanby SH. Oxford Handbook of Transcranial Stimulation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 13–23, 25–32. ISBN 0-19-856892-4.

- ↑ Roth, BJ; MacCabee, PJ; Eberle, LP; Amassian, VE; Hallett, M; Cadwell, J; Anselmi, GD; Tatarian, GT (1994). "In vitro evaluation of a 4-leaf coil design for magnetic stimulation of peripheral nerve". Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology/Evoked Potentials Section 93 (1): 68–74. doi:10.1016/0168-5597(94)90093-0. PMID 7511524.

- ↑ http://www.scholarpedia.org/article/Transcranial_magnetic_stimulation

- ↑ Barker, AT; Jalinous, R; Freeston, IL (1985). "Non-Invasive Magnetic Stimulation of Human Motor Cortex". The Lancet 325 (8437): 1106–1107. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(85)92413-4. PMID 2860322.

- ↑ Merton, PA; Morton, HB (1980). "Stimulation of the cerebral cortex in the intact human subject". Nature 285 (5762): 227. doi:10.1038/285227a0. PMID 7374773.

- ↑ (1) Martin, PI; Naeser, MA; Ho, M; Treglia, E; Kaplan, E; Baker, EH; Pascual-Leone, A (2009). "Research with Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in the Treatment of Aphasia". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports 9 (6): 451–458. doi:10.1007/s11910-009-0067-9. PMC 2887285. PMID 19818232.

(2) Corti, M; Patten, C; Triggs, W (2012). "Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of Motor Cortex after Stroke". American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation 91 (3): 254–270. doi:10.1097/PHM.0b013e318228bf0c. PMID 22042336. - ↑ Kleinjung, T; Vielsmeier, V; Landgrebe, M; Hajak, G; Langguth, B (2008). "Transcranial magnetic stimulation: a new diagnostic and therapeutic tool for tinnitus patients". The international tinnitus journal 14 (2): 112–8. PMID 19205161.

- ↑ Lefaucheur, JP (2009). "Treatment of Parkinson’s disease by cortical stimulation". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics 9 (12): 1755–1771. doi:10.1586/ern.09.132. PMID 19951135.

(2) Arias-Carrión, O (2008). "Basic mechanisms of rTMS: Implications in Parkinson's disease". International Archives of Medicine 1 (1): 2. doi:10.1186/1755-7682-1-2. PMC 2375865. PMID 18471317. - ↑ Nizard J; Lefaucher J-P; Helbert M; de Chauvigny E; Nguyen J-P (2012). "Non-invasive stimulation therapies for the treatment of chronic pain". Discovery Medicine 14 (74): 21–31. ISSN 1539-6509. PMID 22846200. Archived from the original on 2014-02-21.

- ↑ (1) Osuch, EA; Benson, BE; Luckenbaugh, DA; Geraci, M; Post, RM; McCann, U (2009). "Repetitive TMS combined with exposure therapy for PTSD: A preliminary study". Journal of Anxiety Disorders 23 (1): 54–59. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.03.015. PMC 2693184. PMID 18455908.

(2) Watts, BV; Landon, B; Groft, A; Young-Xu, Y (2012). "A sham controlled study of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for posttraumatic stress disorder". Brain Stimulation 5 (1): 38–43. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2011.02.002. PMID 22264669. - ↑ Marangell, LB; Martinez, M; Jurdi, RA; Zboyan, H (2007). "Neurostimulation therapies in depression: a review of new modalities". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 116 (3): 174–181. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01033.x. PMID 17655558.

- ↑ Brunoni, A. R.; Lopes, M.; Kaptchuk, T. J.; Fregni, F. (2009). Hashimoto, Kenji, ed. "Placebo Response of Non-Pharmacological and Pharmacological Trials in Major Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". PLoS ONE 4 (3): e4824. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004824. PMC 2653635. PMID 19293925.

- ↑ Broadbent, H. J.; Van Den Eynde, F.; Guillaume, S.; Hanif, E. L.; Stahl, D.; David, A. S.; Campbell, I. C.; Schmidt, U. (2011). "Blinding success of rTMS applied to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in randomised sham-controlled trials: A systematic review". World Journal of Biological Psychiatry 12 (4): 240. doi:10.3109/15622975.2010.541281. PMID 21426265.

Further reading

- Wassermann, EM; Epstein, CM; Ziemann, U; Walsh, V; Paus, T; Lisanby, SH (2008). Oxford Handbook of Transcranial Stimulation (Oxford Handbooks). Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0-19-856892-4.

- Freeston, I; Barker, A (2007). "Transcranial magnetic stimulation". Scholarpedia 2 (10): 2936. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.2936.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Transcranial magnetic stimulation. |