Trans-Siberian Railway

| Trans-Siberian Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

km | Station | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

284 | Yaroslavl | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

2706 | Irtysh River | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

3332 | Ob River | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

4098 | Krasnoyarsk | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

4516 | Taishet | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

5642 | Ulan Ude | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

8515 | AmurJ.A. Oblast - Khabarovsk Krai border | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

9289 | Vladivostok | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

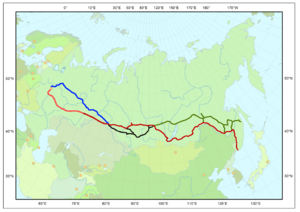

The Trans-Siberian Railway (TSR, Russian: Транссиби́рская магистра́ль, tr. Transsibirskaya Magistral; IPA: [trənsʲsʲɪˈbʲirskəjə məgʲɪˈstralʲ]) is a network of railways connecting Moscow with the Russian Far East and the Sea of Japan.[1] With a length of 9,289 km (5,772 mi),[2] it is the longest railway line in the world. There are connecting branch lines into Mongolia, China and North Korea. It has connected Moscow with Vladivostok since 1916, and is still being expanded.

It was built from 1891 to 1916 under the supervision of Russian government ministers who were personally appointed by Tsar Alexander III and by his son, Tsar Nicholas II. Even before it had been completed, it attracted travellers who wrote of their adventures.[3]

Route description

The Trans-Siberian Railway is often associated with the main transcontinental Russian line that connects hundreds of large and small cities of the European and Asian parts of Russia. At 9,259 kilometres (5,753 miles),[4] spanning a record seven time zones and taking eight days to complete the journey, it is the third-longest single continuous service in the world, after the Moscow–Pyongyang 10,267 kilometres (6,380 mi)[5] and the Kiev–Vladivostok 11,085 kilometres (6,888 mi)[6] services, both of which also follow the Trans-Siberian for much of their routes.

The main route of the Trans-Siberian Railway begins in Moscow at Yaroslavsky Vokzal, runs through Yaroslavl, Chelyabinsk, Omsk, Novosibirsk, Irkutsk, Ulan-Ude, Chita and Khabarovsk to Vladivostok via southern Siberia.

A second primary route is the Trans-Manchurian, which coincides with the Trans-Siberian east of Chita as far as Tarskaya (a stop 12 km (7 mi) east of Karymskoye, in Chita Oblast), about 1,000 km (621 mi) east of Lake Baikal. From Tarskaya the Trans-Manchurian heads southeast, via Harbin and Mudanjiang in China's Northeastern Provinces (from where a connection to Beijing is used by one of the Moscow–Beijing trains), joining with the main route in Ussuriysk just north of Vladivostok. This is the shortest and the oldest railway route to Vladivostok. Some trains split at Shenyang, China, with a portion of the service continuing to Pyongyang, North Korea.

The third primary route is the Trans-Mongolian Railway, which coincides with the Trans-Siberian as far as Ulan-Ude on Lake Baikal's eastern shore. From Ulan-Ude the Trans-Mongolian heads south to Ulaan-Baatar before making its way southeast to Beijing.

In 1991, a fourth route running further to the north was finally completed, after more than five decades of sporadic work. Known as the Baikal Amur Mainline (BAM), this recent extension departs from the Trans-Siberian line at Taishet several hundred miles west of Lake Baikal and passes the lake at its northernmost extremity. It crosses the Amur River at Komsomolsk-na-Amure (north of Khabarovsk), and reaches the Tatar Strait of the Sea of Japan at Sovetskaya Gavan.

On 13 October 2011 a train from Khasan made its inaugural run to Rajin in North Korea.[7]

History

Demand and design

In the late 1800s, the development of Siberia was hampered by poor transport links within the region, as well as with the rest of the country. Aside from the Great Siberian Route, good roads suitable for wheeled transport were rare. For about five months of the year, rivers were the main means of transport. During the cold half of the year, cargo and passengers traveled by horse-drawn sleds over the winter roads, many of which were the same rivers, but ice-covered.

The first steamboat on the River Ob, Nikita Myasnikov's Osnova, was launched in 1844. But early beginnings were difficult, and it was not until 1857 that steamboat shipping started developing on the Ob system in a serious way. Steamboats started operating on the Yenisei in 1863, on the Lena and Amur in the 1870s.

While the comparative flatness of Western Siberia was at least fairly well served by the gigantic Ob–Irtysh–Tobol–Chulym river system, the mighty rivers of Eastern Siberia—the Yenisei, the upper course of the Angara River (the Angara below Bratsk was not easily navigable because of the rapids), and the Lena — were mostly navigable only in the north-south direction. An attempt to partially remedy the situation by building the Ob-Yenisei Canal was not particularly successful. Only a railway could be a real solution to the region's transport problems.

The first railway projects in Siberia emerged after the completion of the Moscow-Saint Petersburg Railway in 1851.[8] One of the first was the Irkutsk–Chita project, proposed by the American entrepreneur Perry Collins and supported by Transport Minister Constantine Possiet with a view toward connecting Moscow to the Amur River, and consequently, to the Pacific Ocean. Siberia's governor, Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky, was anxious to advance the colonisation of the Russian Far East, but his plans could not materialise as long as the colonists had to import grain and other food from China and Korea.[9] It was on Muravyov's initiative that surveys for a railway in the Khabarovsk region were conducted.

Before 1880, the central government had virtually ignored these projects, because of the weakness of Siberian enterprises, a clumsy bureaucracy, and fear of financial risk. By 1880, there were a large number of rejected and upcoming applications for permission to construct railways to connect Siberia with the Pacific, but not Eastern Russia. This worried the government and made connecting Siberia with Central Russia a pressing concern. The design process lasted 10 years. Along with the route actually constructed, alternative projects were proposed:

- Southern route: via Kazakhstan, Barnaul, Abakan and Mongolia.

- Northern route: via Tyumen, Tobolsk, Tomsk, Yeniseysk and the modern Baikal Amur Mainline or even through Yakutsk.

Railwaymen fought against suggestions to save funds, for example, by installing ferryboats instead of bridges over the rivers until traffic increased. The designers insisted and secured the decision to construct an uninterrupted railway.

Unlike the rejected private projects that intended to connect the existing cities demanding transport, the Trans-Siberian did not have such a priority. Thus, to save money and avoid clashes with land owners, it was decided to lay the railway outside the existing cities. Tomsk was the largest city, and the most unfortunate, because the swampy banks of the Ob River near it were considered inappropriate for a bridge. The railway was laid 70 km (43 mi) to the south (instead crossing the Ob at Novonikolaevsk, later renamed Novosibirsk); just a dead-end branch line connected with Tomsk, depriving the city of the prospective transit railway traffic and trade.

Construction

In March 1890, the future Tsar Nicholas II personally inaugurated the construction of the Far East segment of the Trans-Siberian Railway during his stop at Vladivostok, after visiting Japan at the end of his journey around the world. Nicholas II made notes in his diary about his anticipation of travelling in the comfort of "the tsar's train" across the unspoiled wilderness of Siberia. The tsar's train was designed and built in St. Petersburg to serve as the main mobile office of the tsar and his staff for travelling across Russia.

Full-time construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway began in 1891 and was put into execution and overseen by Sergei Witte, who was then finance minister.

Similar to the First Transcontinental Railroad in the US, Russian engineers started construction at both ends and worked towards the centre. From Vladivostok the railway was laid north along the right bank of the Ussuri River to Khabarovsk at the Amur River, becoming the Ussuri Railway.

In 1890, a bridge across the Ural River was built and the new railway entered Asia. The bridge across the Ob River was built in 1898 and the small city of Novonikolaevsk, founded in 1883, grew into the large Siberian city of Novosibirsk. In 1898 the first train reached Irkutsk and the shores of Lake Baikal about 60 kilometres (37 miles) east of the city. The railway ran on to the east, across the Shilka and Amur rivers and soon reached Khabarovsk. The Vladivostok to Khabarovsk section was built slightly earlier, in 1897.

Russian soldiers, as well as convict labourers from Sakhalin and other places were used for building the railway.

Lake Baikal is more than 640 kilometres (400 miles) long and more than 1,600 metres (5,200 feet) deep. Until the Circum-Baikal Railway was built the line ended on either side of the lake. The ice-breaking train ferry SS Baikal built in 1897 and smaller ferry SS Angara built in about 1900, made the four-hour crossing to link the two railheads.[10][11] The Russian admiral and explorer Stepan Makarov (1849–1904) designed Baikal and Angara but they were built in Newcastle upon Tyne, England, by Armstrong Whitworth. They were "knock down" vessels; that is, each ship was bolted together in England, every part of the ship was marked with a number, the ship was disassembled into many hundreds of parts and transported in kit form to Listvyanka where a shipyard was built especially to reassemble them.[11] Their boilers, engines and some other components were built in Saint Petersburg[11] and transported to Listvyanka to be installed. Baikal had 15 boilers, four funnels, and was 64 metres (210 ft) long. She could carry 24 railway coaches and one locomotive on her middle deck.[10][11] Angara was smaller, with two funnels.[10][11]

Completion of the Circum-Baikal Railway in 1904 bypassed the ferries, but from time to time the Circum-Baikal Railway suffered from derailments or rockfalls so both ships were held in reserve until 1916.[10][11] Baikal was burnt out and destroyed in the Russian Civil War[10][11] but Angara survives.[10] She has been restored and is permanently moored at Irkutsk where she serves as an office and a museum.[10]

In winter, sleighs were used to move passengers and cargo from one side of the lake to the other until the completion of the Lake Baikal spur along the southern edge of the lake.

With the Amur River Line north of the Chinese border being completed in 1916, there was a continuous railway from Petrograd to Vladivostok that remains to this day the world's longest railway line. Electrification of the line, begun in 1929 and completed in 2002, allowed a doubling of train weights to 6,000 tonnes.

The additional Chinese Eastern Railway was constructed as the Russo-Chinese part of the Trans-Siberian Railway, connecting Russia with China and providing a shorter route to Vladivostok. A Russian staff and administration based in Harbin operated it.

Effects

As Siberian agriculture began, from around 1869, to send cheap grain westwards, agriculture in Central Russia was still under economic pressure after the end of serfdom, which was formally abolished in 1861. Thus, to defend the central territory and to prevent possible social destabilisation, in 1896 the Tsarist government introduced the Chelyabinsk tariff-break (Челябинский тарифный перелом), a tariff barrier for grain passing through Chelyabinsk, and a similar barrier in Manchuria. This measure changed the nature of export: mills emerged to produce bread from grain in Altai Krai, Novosibirsk and Tomsk, and many farms switched to corn (maize) production. From 1896 until 1913 Siberia exported on average 501,932 tonnes (30,643,000 pood) of bread (grain, flour) annually.[12]

The Trans-Siberian Railway also brought with it millions of peasant-migrants from the Western regions of Russia and Ukraine.[13] Between 1906 and 1914, the peak migration years, about 4 million peasants arrived in Siberia.[14]

The railway immediately filled to capacity with local traffic, mostly wheat. Despite the low speed and low possible weights of trains, the railway fulfilled its promised role as a transit route between Europe and East Asia. During the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, military traffic to the east almost disrupted the flow of civil freight.

War and revolution

In the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05), the Trans-Siberian Railway was seen as one of the reasons Russia lost the war. The track was a single track and as such could only allow train travel in one direction. This caused significant strategic and supply difficulties for the Russians, as they could not move resources to and from the front as quickly as would be necessary, as a goods train carrying supplies, men and ammunition coming from west to east would have to wait in the sidings, whilst troops and injured personnel in a troop train travelling from east to west went along the line. Thus the Japanese were quickly able to advance whilst the Russians were awaiting necessary troops and supplies. After the Russian Revolution of 1917, the railway served as the vital line of communication for the Czechoslovak Legion and the allied armies that landed troops at Vladivostok during the Siberian Intervention of the Russian Civil War. These forces supported the White Russian government of Admiral Alexander Kolchak, based in Omsk, and White Russian soldiers fighting the Bolsheviks on the Ural front. The intervention was weakened, and ultimately defeated, by partisan fighters who blew up bridges and sections of track, particularly in the volatile region between Krasnoyarsk and Chita.[15][16][17]

The Trans-Siberian Railway also played a very direct role during parts of Russia's history, with the Czechoslovak Legion using heavily armed and armoured trains to control large amounts of the railway (and of Russia itself) during the Russian Civil War at the end of World War I.[18] As one of the few organised fighting forces left in the aftermath of the imperial collapse, and before the Red Army took control, the Czechs and Slovaks were able to use their organisation and the resources of the railway to establish a temporary zone of control before eventually continuing onwards towards Vladivostok, from where they emigrated back to Czechoslovakia through Vancouver in Canada, through Canada to Europe or the Panama Canal to Europe also through Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Port Said and Triest.

World War II

During World War II, the Trans-Siberian Railway played an important role in the supply of the powers fighting in Europe.

In the first two years of the war, when Germany's merchant shipping was interdicted by the Western Allies, the railway was an essential link between Germany and Japan. One commodity vital for the German war effort was natural rubber, which Japan was able to source from South-East Asia, particularly French Indochina. As of March 1941, an average of 300 tonnes of natural rubber were transported daily en route for Germany.

At this time, a number of Jews and anti-Nazis used the Trans-Siberian Railway to escape Europe, including the mathematician Kurt Gödel and the mother of the actor Heinz Bernard[19] Several thousand Jewish refugees were able to make this trip thanks to the Japanese visas issued by the Japanese consul, Chiune Sugihara, in Kaunas, Lithuania. Typically they would travel east on the Trans-Siberian Railway to the Pacific Ocean where they would board a ship bound for the USA.

The situation reversed after 22 June 1941. By invading the Soviet Union, Germany cut off its only reliable trade route to Japan. Instead, it had to use fast merchant ships (blockade runners) and later large oceanic submarines in an attempt to evade the allied maritime patrols. On the other hand, the USSR became the recipient of lend lease supplies from the USA. Even though Japan went to war with the USA, it was anxious to preserve good relations with the USSR and, despite German complaints, usually allowed Soviet ships to sail between the USA and Russia's Pacific ports unmolested[20] This contrasted with Germany and Britain's behavior, whose navies would destroy or capture neutrals' ships sailing to their respective adversaries. As a result, the Pacific Route – involving crossing the northern Pacific Ocean and the Trans-Siberian Railway – became the safest connection between the USA and the USSR. Accordingly, it accounted for as much freight as the two other routes (North Atlantic–Arctic and Iranian) combined.

From 1941 to 1942 the railway also played an important role in relocating Soviet industries from European Russia to Siberia in the face of the German invasion. The railway also transported Soviet troops east from Germany to the Japanese front in preparation for the Soviet–Japanese War of August 1945.

The railway today

The Trans-Siberian line remains the most important transport link within Russia; around 30% of Russian exports travel on the line. While it attracts many foreign tourists, it gets most of its use from domestic passengers.

Today the Trans-Siberian Railway carries about 200,000 containers per year to Europe. Russian Railways intends to at least double the volume of container traffic on the Trans-Siberian and is developing a fleet of specialised cars and increasing terminal capacity at the ports by a factor of 3 to 4. By 2010, the volume of traffic between Russia and China could reach 60 million tons (54 million tonnes), most of which will go by the Trans-Siberian.[21]

With perfect coordination of the participating countries' railway authorities, a trainload of containers can be taken from Beijing to Hamburg, via the Trans-Mongolian and Trans-Siberian lines in as little as 15 days, but typical cargo transit times are usually significantly longer[22] and typical cargo transit time from Japan to major destinations in European Russia was reported as around 25 days.[23]

According to a 2009 report, the best travel times for cargo block trains from Russia's Pacific ports to the western border (of Russia, or perhaps of Belarus) were around 12 days, with trains making around 900 km (559 mi) per day, at a maximum operating speed of 80 km/h (50 mph). However, in early 2009 Russian Railways announced an ambitious "Trans-Siberian in Seven Days" programme; according to this plan, $11 billion will be invested over the next five years to make it possible for goods traffic to cover the same 9,000 km (5,592 mi) distance in just seven days. The plan will involve increasing the cargo trains' speed to 90 km/h (56 mph) in 2010–12, and, at least on some sections, to 100 km/h (62 mph) by 2015. At these speeds, goods trains will be able to cover 1,500 km (932 mi) per day.[24]

Developments in shipping

On 11 January 2008, China, Mongolia, Russia, Belarus, Poland and Germany agreed to collaborate on a cargo train service between Beijing and Hamburg.[25]

The railway can typically deliver containers in ⅓ to ½ of the time of a sea voyage, and in late 2009 announced a 20% reduction in its container shipping rates. With its 2009 rate schedule, the TSR will transport a forty-foot container to Poland from Yokohama for $2,820, or from Pusan for $2,154.[26]

One of the most complicating factors related to such ventures is the fact that the CIS states' broad railway gauge is incompatible with China and Western and Central Europe's standard gauge. Therefore, a train travelling from China to Western Europe would encounter gauge breaks twice: at the Chinese-Mongolian or the Chinese-Russian frontier and at the Ukrainian or the Belorussian border with Central European countries.

Gallery

-

Start of Trans-Siberian railway in Moscow.

-

Bridge over Kama River near Perm

-

Bashkir switchman near the town Ust' Katav on the Yuryuzan River between Ufa and Cheliabinsk in the Ural Mountains region, c. 1910

-

View from the rear platform of the Simskaia railway station of the Samara-Zlatoust Railway, c. 1910

-

Snow in the end of April, Nazyvayevsk station, Siberia.

-

The train ferry SS Baikal in service on Lake Baikal

-

Train entering a Circum-Baikal tunnel west of Kultuk

-

Vladivostok terminus of the Trans-Siberian Railway

Routes

In general, the lower the train number the fewer stops it makes and therefore the faster the journey. The train number makes no difference in the duration of border crossings.

Trans-Siberian line

A commonly used main line route is as follows. Distances and travel times are from the schedule of train No.002M, Moscow-Vladivostok.[4]

- Moscow, Yaroslavsky Rail Terminal (0 km, Moscow Time).

- Vladimir (210 km (130 mi), MT)

- Nizhny Novgorod (461 km (286 mi), 6 hours, MT) on the Volga River.

- Kirov (917 km (570 mi), 13 hours, MT) on the Vyatka River.

- Perm (1,397 km (868 mi), 20 hours, MT+2) on the Kama River

- Official boundary between Europe and Asia (1,777 km), marked by a white obelisk.

- Yekaterinburg (1,816 km (1,128 mi), 1 day 2 hours, MT+2) in the Urals, still called by its old Soviet name Sverdlovsk in most timetables.

- Tyumen (2,104 km)

- Omsk (2,676 km (1,663 mi), 1 day 14 hours, MT+3) on the Irtysh River

- Novosibirsk (3,303 km (2,052 mi), 1 day 22 hours, MT+3) on the Ob River. Turk-Sib railway branches from here.

- Krasnoyarsk (4,065 km (2,526 mi), 2 days 11 hours, MT+4) on the Yenisei River

- Taishet (4,483 km), junction with the Baikal-Amur Mainline

- Irkutsk (5,153 km (3,202 mi), 3 days 4 hours, MT+5) near Lake Baikal's southern extremity

- Ulan Ude (5,609 km (3,485 mi), 3 days 12 hours, MT+5) eastern shore of Lake Baikal

- Junction with the Trans-Mongolian line (5,622 km)

- Chita (6,166 km (3,831 mi), 3 days 22 hours, MT+6)

- Junction with the Trans-Manchurian line at Tarskaya (6,274 km)

- Birobidzhan (8,312 km (5,165 mi), 5 days 13 hours), the capital of Jewish Autonomous Region

- Khabarovsk (8,493 km (5,277 mi), 5 days 15 hours, MT+7) on the Amur River

- Ussuriysk (9,147 km), junction with the Trans-Manchurian line and Korea branch (It is located in Varanovsky, 13 km (8 miles) from Ussuriysk)

- Vladivostok (9,289 km (5,772 mi), 6 days 4 hours, MT+7), on the Pacific Ocean

Services to North Korea continue from Ussuriysk via:

- Primorsk (9,257 km (5,752 mi), 6 days 14 hours, MT+7)

- Khasan (9,407 km (5,845 mi), 6 days 19 hours, MT+7, border with North Korea)

- Tumangang (9,412 km (5,848 mi), 7 days 10 hours, MT+6, North Korean side of the border)

- Pyongyang (10,267 km (6,380 mi), 9 days 2 hours, MT+6)

There are many alternative routings between Moscow and Siberia. For example:

- Some trains would leave Moscow from Kazansky Rail Terminal instead of Yaroslavsky Rail Terminal; this would save some 20 km (12 mi) off the distances, because it provides a shorter exit from Moscow onto the Nizhny Novgorod main line.

- One can take a night train from Moscow's Kursky Rail Terminal to Nizhny Novgorod, make a stopover in the Nizhny and then transfer to a Siberia-bound train

- From 1956 to 2001 many trains went between Moscow and Kirov via Yaroslavl instead of Nizhny Novgorod. This would add some 29 km (18 mi) to the distances from Moscow, making the total distance to Vladivostok at 9,288 km (5,771 mi).

- Other trains get from Moscow (Kazansky Terminal) to Yekaterinburg via Kazan.

- Between Yekaterinburg and Omsk it is possible to travel via Kurgan Petropavlovsk (in Kazakhstan) instead of Tyumen.

- One can bypass Yekaterinburg altogether by travelling via Samara, Ufa, Chelyabinsk and Petropavlovsk; this was historically the earliest configuration.

Depending on the route taken, the distances from Moscow to the same station in Siberia may differ by several tens of km.

Trans-Manchurian line

The Trans-Manchurian line, as e.g. used by train No.020, Moscow-Beijing[27] follows the same route as the Trans-Siberian between Moscow and Chita and then follows this route to China:

- Branch off from the Trans-Siberian-line at Tarskaya (6,274 km (3,898 mi) from Moscow)

- Zabaikalsk (6,626 km), Russian border town; there is a break-of-gauge

- Manzhouli (6,638 km (4,125 mi) from Moscow, 2,323 km (1,443 mi) from Beijing), Chinese border town

- Harbin (7,573 km (4,706 mi), 1,388 km)

- Changchun (7,820 km (4,859 mi) from Moscow)

- Beijing (8,961 km (5,568 mi) from Moscow)

The express train (No. 020) travel time from Moscow to Beijing is just over six days.

There is no direct passenger service along the entire original Trans-Manchurian route (i.e., from Moscow or anywhere in Russia, west of Manchuria, to Vladivostok via Harbin), due to the obvious administrative and technical (gauge break) inconveniences of crossing the border twice. However, assuming sufficient patience and possession of appropriate visas, it is still possible to travel all the way along the original route, with a few stopovers (e.g. in Harbin, Grodekovo and Ussuriysk).[28][29][30] Such an itinerary would pass through the following points from Harbin east:

- Harbin (7,573 km (4,706 mi) from Moscow)

- Mudanjiang (7,928 km)

- Suifenhe (8,121 km), the Chinese border station

- Grodekovo (8,147 km), Russia

- Ussuriysk (8,244 km)

- Vladivostok (8,356 km)

Trans-Mongolian line

The Trans-Mongolian line follows the same route as the Trans-Siberian between Moscow and Ulan Ude, and then follows this route to Mongolia and China:

- Branch off from the Trans-Siberian line (5,655 km (3,514 mi) from Moscow)

- Naushki (5,895 km (3,663 mi), MT+5), Russian border town

- Russian–Mongolian border (5,900 km (3,666 mi), MT+5)

- Sükhbaatar (5,921 km (3,679 mi), MT+5), Mongolian border town

- Ulan Bator (6,304 km (3,917 mi), MT+5), the Mongolian capital

- Zamyn-Üüd (7,013 km (4,358 mi), MT+5), Mongolian border town

- Erenhot (842 km (523 mi) from Beijing, MT+5), Chinese border town

- Datong (371 km (231 mi), MT+5)

- Beijing (MT+5)

Cultural importance

- The Trans-Siberian Railway is the theme for the Trans-Siberian Railway Panorama and 1900 Trans-Siberian Railway Fabergé egg.

- In the anime Blood +,the main character Saya Otonashi has a fight with chiropteans in her travel by the Trans-Siberian express heading for Ekaterinburg.

- In the videogame Syberia the protagonist travels by train through Russia/Siberia – a clear reference to the Trans-Siberian Railway.

- The Corto Maltese comic Corte sconta detta arcana/Corto Maltese en Sibérie has the Trans-Siberian Railway as part of the story that takes place in the Russian Revolutionary period of the 20th century.

- The cult film Horror Express starring Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee and Telly Savalas is set aboard the railway.

- In the play Fiddler on the Roof and the film version, Tevye's daughter, Hodel, takes the Trans-Siberian Railway to Siberia after her fiancé is exiled there.

- The 2008 thriller Transsiberian takes place on the railway.

- The 2012 Television show An Idiot Abroad features Karl Pilkington travelling the length of the railway.

- Henry Rollins has talked of his trip on the Trans-Siberian Express during his speaking engagements.

See also

- Baikal–Amur Mainline

- Famous trains

- History of Siberia

- Russian gauge

- Russian Railways

- Sibirjak

- Starlight Express, a train musical in which a character is modeled on the Trans-Siberian Express.

- Trans-Siberian Railway Panorama

References

- ↑ "Lonely Planet Guide to the Trans-Siberian Railway" (PDF). Lonely Planet Publications. Retrieved 2013.

- ↑ "The Trans-Siberian Railway – the second longest railway in the world". January 31, 2011.

- ↑ Meakin, Annette, A Ribbon of Iron (1901), reprinted in 1970 as part of the Russia Observed series (Arno Press/New York Times)(ISBN 0405303509).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "CIS railway timetable, route No. 002, Moscow-Vladivostok". Archived from the original on December 3, 2009.

- ↑ "CIS railway timetable, route No. 002, Moscow-Pyongyang". Archived from the original on December 3, 2009.

- ↑ "CIS railway timetable, route No. 350, Kiev-Vladivostok". Archived from the original on December 3, 2009.

- ↑ "Russia train makes inaugural run to NKorea". October 13, 2011.

- ↑ Alexeev, V. V.; Bandman, M. K.; Kuleshov—Novosibirsk, V. V., eds. (2002). Problem Regions of Resource Type: Economical Integration of European North-East, Ural and Siberia. IEIE. ISBN 5-89665-060-4.

- ↑ March, G. Patrick (1996). Eastern Destiny: Russia in Asia and the North Pacific. Praeger/Greenwood. pp. 152–53. ISBN 0-275-95648-2.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 "Irkutsk: Ice-Breaker "Angara"". Lake Baikal Travel Company. Lake Baikal Travel Company. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 Babanine, Fedor (2003). "Circumbaikal Railway". Lake Baikal Homepage. Fedor Babanine. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- ↑ Храмков, А. А. (2001). "Железнодорожные перевозки хлеба из Сибири в западном направлении в конце XIX—начале XX вв" [Railroad transportation of bread from Siberia westwards in the late 19th–early 20th centuries]. Предприниматели и предпринимательство в Сибири. Вып.3 [Entrepreneurs and business undertakings in Siberia. 3rd issue]. Барнаул: Изд-во АГУ. ISBN 5-7904-0195-3.

- ↑ Subtelny, Orest (2000). Ukraine: a history. University of Toronto Press. p. 262. ISBN 0-8020-8390-0.

- ↑ Dronin, N. M.; Bellinger, E. G. (2005). Climate dependence and food problems in Russia, 1900–1990: the interaction of climate and agricultural policy and their effect on food problems. Central European University Press. p. 38. ISBN 963-7326-10-3.

- ↑ Isitt, Benjamin (June 2006). "Mutiny from Victoria to Vladivostok, December 1918". Canadian Historical Review 87 (2): 223–264. doi:10.3138/chr/87.2.223.

- ↑ "Canada's Siberian Expedition Digital Archive".

- ↑ "Siberian Expedition website".

- ↑ Willmott, H.P. (2003). First World War. Dorling Kindersley. p. 251.

- ↑ Lowenstein, Jonathan (April 26, 2010). "The Journey of a Lifetime: my grandmother's escape on the Trans-Siberian railway". Telaviv1.

- ↑ Martin 1969, p. 174

- ↑ "Transsiberian Railway (from Russian Railways official website)". Eng.rzd.ru. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ↑ Donahue, Patrick (January 24, 2008). "China-to-Germany Cargo Train Completes Trial Run in 15 Days". Bloomberg.com.

- ↑ Kachi, Hiroyuki (July 20, 2007). "Mitsui talking to Russian railway operator on trans-Siberian freight service". MarketWatch.com.

- ↑ "Trans-Siberian in seven days". Railway Gazette International. May 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Beijing to Hamburg fast cargo rail link planned". The China Post. January 11, 2008. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Chapter 4: Freight Rates" (PDF). Review of Maritime Transport (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development): 89. 2010. ISSN 0566-7682. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- ↑ "CIS railway timetable, route No. 020, Moscow-Beijing". Archived from the original on December 3, 2009.

- ↑ "Harbin-Suifenhe train schedule".

- ↑ "Grodekovo-Harbin schedule". November 2006. (Note that Russian train sites give incorrect kilometre distance between Chinese stations).

- ↑ "Grodekovo-Ussuriysk schedule". November 2006.

Further reading

- Ames, Edward (1947). "A century of Russian railroad construction: 1837-1936". American Slavic and East European Review: 57–74.

- Dawson Jr, John W (2002). "Max Dehn, Kurt Gödel, and the Trans-Siberian escape route". Notices of the AMS (49.9).

- Marks, S.G. (1991). Road to Power: The Trans-Siberian Railroad and the Colonization of Asian Russia, 1850–1917. ISBN 0-8014-2533-6.

- Faulstich, Edith M. (1972–1977). The Siberian Sojourn. Yonkers, N.Y.

- Metzer, Jacob (1976). "Railroads in Tsarist Russia: Direct gains and implications". Explorations in Economic History (13.1): 85–111.

- Miller, Elisa B. (1978). "The Trans-Siberian landbridge, a new trade route between Japan and Europe: issues and prospects". Soviet Geography (19.4): 223–243.

- North, Robert N. (1979). Transport in western Siberia: Tsarist and Soviet development. University of British Columbia Press.

- Reichman, Henry (1988). "The 1905 Revolution on the Siberian Railroad". Russian Review 47 (1): 25–48. doi:10.2307/130442.

- Richmond, Simon (2009). Trans-Siberian Railway. Lonely Planet. Guide book for travelers

- Thomas, Bryn (2003). The Trans-Siberian Handbook (6th ed.). Trailblazer. ISBN 1-873756-70-4. Guide book for travelers

- Tupper, Harmon (1965). To the great ocean: Siberia and the Trans-Siberian Railway. Little, Brown.

- Westwood, John Norton (1964). A history of Russian railways. G. Allen and Unwin.

- Калиничев, В. П. (1991). Великий Сиберский путь (историко-экономический очерк) (in Russian). Москва: Транспорт. ISBN 5-277-00758-X.

- Omrani, Bijan (2010). Asia Overland: Tales of Travel on the Trans-Siberian and Silk Road. Odyssey Publications. ISBN 962-217-811-1.

- Wolmar, Christian (2013). To the Edge of the World. PublicAffairs/Atlantic Publications. ISBN 978-1-61039-452-9.

External links

![]() Media related to Trans-Siberian railway at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Trans-Siberian railway at Wikimedia Commons

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Trans-Siberian Railway. |

- Russian Railways - official website

- Overview of passenger travel today

- "A 1903 map of Trans-Siberian railway". Archived from the original on 11 Jan 2013.

- Guide to the Great Siberian Railway (1900)

- Mikhailoff, M. (May 1900). ""The Great Siberian Railway"". the North American Review 170 (522).

- Manley, Deborah, ed. (January 2009). The Trans-Siberian Railway: A Traveller's Anthology. ISBN 1-904955-49-5.

- Winchester, Clarence, ed. (1936), "The Trans-Siberian Express", Railway Wonders of the World, pp. 451–457 illustrated description of the route and the train