Toyohara Kunichika

| Toyohara Kunichika | |

|---|---|

|

Toyohara Kunichika 1897, Photograph by Hiraki | |

| Born |

Ōshima Yasohachi 1835 Edo (present-day Tokyo), Japan |

| Died |

1900 Tokyo |

| Other names |

|

| Known for | Woodblock prints of kabuki actors, beautiful women |

Toyohara Kunichika (Japanese: 豊原 国周; 30 June 1835 – 1 July 1900) was a Japanese woodblock print artist. Talented as a child, at about thirteen he became a student of Tokyo's then-leading print maker, Utagawa Kunisada. His deep appreciation and knowledge of kabuki drama led to his production primarily of ukiyo-e actor-prints, which are woodblock prints of kabuki actors and scenes from popular plays of the time.

An alcoholic and womanizer, Kunichika also portrayed women deemed beautiful (bijinga), contemporary social life, and a few landscapes and historical scenes. He worked successfully in the Edo period, and carried those traditions into the Meiji period. To his contemporaries and now to some modern art historians, this has been seen as a significant achievement during a transitional period of great social and political change in Japan's history.[1]

Early life and education

The artist who became known as Toyohara Kunichika was born Ōshima Yasohachi on June 30, 1835, in the Kyōbashi district, a merchant and artisan area of Edo (present-day Tokyo). His father, Ōshima Kyujū, was the proprietor of a sentō (public bathhouse), the Ōshūya. An indifferent family man, and poor businessman, he lost the bathhouse sometime in Yasohachi's childhood. The boy's mother, Arakawa Oyae, was the daughter of a teahouse proprietor. At that time, commoners of a certain social standing could ask permission to alter the family name (myōji gomen). To distance themselves from the father's failure, the family took the mother's surname, and the boy became Arakawa Yasohachi.[2]

Little is known about his childhood except that, as a youth, Yasohachi earned a reputation as a prankster and drew complaints from his neighbors, and that at nine he was involved in a fight at the Sanno Festival in Asakusa .[3] At age ten he was apprenticed to a thread and yarn store. However, because he preferred painting and sketching to learning the dry goods trade, at eleven he moved to a shop near his father's bathhouse. There he helped in the design of Japanese lampshades called andon, consisting of a wooden frame with a paper cover.[4] When he was twelve, his older brother, Chōkichi, opened a raised picture[5] shop, and Yasohachi drew illustrations for him.[2]

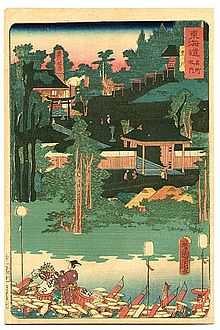

It is believed that around age twelve Yasohachi began to study with Toyohara (Ichiōsai) Chikanobu (not to be confused with Kunichika’s student Toyohara Chikanobu). At the same time he designed actor portraits for battledores sold by a shop called Meirindo. His teacher gave him the name "Kazunobu".[4] It may have been on the recommendation of Chikanobu that the boy was accepted the following year as an apprentice in the studio of Utagawa Kunisada,[6] the leading and most prolific print maker of the mid-19th century.[7] By 1854 the young artist had made his first confirmed signed print[8] and had taken the name "Kunichika", a composite of the names of this two teachers, Kunisada and Chikanobu.[9] His early work was derivative of the Utagawa style and some of his prints were outright copies (an accepted practice of the time).[10] While working in Kunisada's studio Kunichika was assigned a commission to make a print illustrating a bird's-eye view of Tenjinbashi Avenue following the terrible earthquake of 1855 that destroyed most of the city. This assignment suggests that he was considered one of Kunisada's better students.[8]

The "prankster" artist got into trouble in 1862 when, in response to a commission for a print illustrating a fight at a theater, he made a "parody print" (mitate-e) which angered the students who had been involved in the fracas. They ransacked Kunichika's house and tried to enter Kunisada's studio by force. His mentor revoked Kunichika's right to use the name he had been given but relented later that year. Decades afterwards Kunichika described himself as greatly "humbled" by the experience.[9]

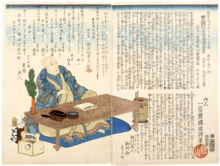

Kunichika's status continued to rise and he was commissioned to create several portraits of his teacher. When Kunisada died in 1865, his student was commissioned to design two memorial portraits. The right panel of the portrait contains an obituary written by the writer, Kanagaki Robun, while the left contains memorial poems written by the three top students, including Kunichika.[8]

Artist on the cusp of a new era

At the time Kunichika began his serious studies the late Edo period, an extension of traditions based on a feudal society, was about to end. The "modern" Meiji era (1868–1912), a time of rapid modernization, industrialization, and extensive contact with the West, was in stark contrast to what had come before.

Ukiyo-e artists had traditionally illustrated urban life and society – especially the theater, for which their prints often served as advertising. The Meiji period brought competition from the new technologies of photography and photoengraving, effectively destroying the careers of most.[11]

As Kunichika matured his reputation as a master of design and of drama grew steadily. In guides rating ukiyo-e artists his name appeared in the top ten in 1865, 1867, and 1885, when he was in eighth, fifth, and fourth place, respectively.[9] In 1867, one year before the collapse of the Tokugawa Shogunate, he received an official commission by the government to contribute ten pictures to the 1867 World Exhibition in Paris.[12] He also had a print at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago.[13]

Kunichika often portrayed beautiful women (bijinga), but his finest works are considered to have been bust, half- and three-quarter length, and close-up or "large-head" portraits of actors, and triptychs that presented "wide-screen" views of plays and popular stories.[14]

Although Kunichika's Meiji-era works remained rooted in the traditions of his teachers, he made an effort to incorporate references to modern technology. In 1869 he did a series jointly with Yoshitoshi, a more "modern" artist in the sense that he depicted faces realistically.[15] In addition, Kunichika experimented with "Western" vanishing point perspective.

The press affirmed that Kunichika's success continued into the Meiji era. In July 1874, the magazine Shinbun hentai said that: "Color woodcuts are one of the specialties of Tokyo, and that Kyôsai, Yoshitoshi, Yoshiiku, Kunichika, and Ginkô are the experts in this area." In September 1874 The same journal held that: "The masters of Ukiyoe: Yoshiiku, Kunichika and Yoshitoshi. They are the most popular Ukiyo-e artists." In 1890, the book Tôkyô meishô doku annai (Famous Views of Tokyo), under the heading of woodblock artist, gave as examples Kunichika, Kunisada, Yoshiiku, and Yoshitoshi. In November 1890 a reporter for the newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun wrote about the specializations of artists of the Utagawa school: "Yoshitoshi was the specialist for warrior prints, Kunichika the woodblock artist known for portraits of actors, and Chikanobu for court ladies."[16] [17]

Contemporary observers noted Kunichika's skillful use of color in his actor prints, but he was also criticized for his choices. Unlike most artists of the period, he made use of strong reds and dark purples, often as background colors, rather than the softer colors that had previously been used. These new colors were made of aniline dyes imported in the Meiji period from Germany. (For the Japanese the color red meant progress and enlightenment in the new era of Western-style progress.)[18]

Like most artists of his era and genre,[19] Kunichika created many series of prints, including: Yoshiwara beauties compared with thirty-six poems; Thirty-two fashionable physiognomies; Sixteen Musashi parodying modern customs; Thirty-six good and evil beauties; Thirty-six modern restaurants; Mirror of the flowering of manners and customs; Fifty-four modern feelings matched with chapters of The Tale of Genji; Scenes of the twenty-four hours parodied; Actors in theatrical hits as great heroes in robber plays; Eight views of bandits parodied.[20]

In 1863 Kunichika was one of a number of artists who contributed landscape prints to two series of famous Tokaido scenes commissioned to commemorate the journey made by the shogun Iemochi from Edo to Kyoto to pay his respects to the emperor. Otherwise, his landscapes were primarily theater sets, or backgrounds for groups of beauties enjoying the out-of-doors. He recorded some popular myths and tales, but rarely illustrated battles. When portraying people he only occasionally showed figures wearing Western dress, despite its growing popularity in Japan. He is known to have done some shunga (erotic art) prints but attribution can be difficult as, like most artists of the time, he did not always sign them. Kunichika had many students but few attained recognition as print artists. In the changing art scene they could not support themselves designing woodblock prints, but had to make illustrations for such popular media as books, magazines and newspapers. His best-known students were Toyohara Chikanobu and Morikawa Chikashige. Both initially followed their master's interest in theater, but later Chikanobu more enthusiastically portrayed women's fashions, and Chikashige did illustrations. Neither is considered by critics to have achieved his master's high reputation.[21]

Kunichika had one female student, Toyohara Chikayoshi, who reportedly became his partner in his later years. Her work reflected the Utagawa style. She competently depicted actors, and the manners and customs of the day.[22]

Personal life

As a young man, Kunichika had a reputation for a beautiful singing voice and as a fine dancer. He is known to have used these talents in amateur burlesque shows.[23]

In 1861 Kunichika married his first wife, Ohana, and in that same year had a daughter, Hana. The marriage is thought not to have lasted long, as he was a womanizer. He fathered two out-of-wedlock children, a girl and a boy, with whom he had no contact, but he does appear to have remained strongly attached to Hana.[24]

Kunichika was described as having an open, friendly and sincere personality.[23] He enjoyed partying with the geishas and prostitutes of the Yoshiwara district, while consuming abundant amounts of alcohol. His greatest passion, however, was said to be the theater, where he was a backstage regular. His appearance said to be shabby. He was constantly in debt and often borrowed money from the kabuki actors he depicted so admiringly.[25] A contemporary said of him: "Print designing, theater and drinking were his life and for him that was enough."[26] A contemporary actor, Matsusuke IV, said that when visiting actors backstage for the purpose of sketching them, Kunichika would not socialize but would concentrate intensely on his work.[27]

Around 1897, his older brother opened the Arakawa Photo shop, and Kunichika worked in the store. Because Kunichika had a dislike for both the store and photography, only one photograph of him exists.[28][29]

In October 1898 Kunichika was interviewed for a series of four articles about him, The Meiji-period child of Edo, which appeared in the Tokyo newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun. In the introduction to the series, the reporter wrote:

...his house is located on the (north) side of Higashi Kumagaya-Inari. Although his residence is just a partitioned tenement house, it has an elegant, latticed door, a nameplate and letterbox. Inside, the entry...leads to a room with worn tatami mats upon which a long hibachi has been placed. The space is also adorned with a Buddhist altar. A cluttered desk stands at the back of the miserable two-tatami room; it is hard to believe that the well-known artist Kunichika lives here...Looking around with a piercing gaze and stroking his long white beard, Kunichika talks about the height of prosperity of the Edokko...[2]

During the interview, Kunichika claimed to have moved 107 times, but it seems more likely that he moved only ten times.[28]

Kunichika died at his home in Honjo (an eastern suburb of Edo) on July 1, 1900 at the age of 65, due to a combination of poor health and bouts of heavy drinking brought on by the death at 39 of his daughter Hana while giving birth to his grandson, Yoshido Ito, some months previously.[28] He was buried at the Shingon Buddhist sect temple of Honryuji in Imado, Asakusa.[16] His grave marker is thought to have been destroyed in a 1923 earthquake, but family members erected a new one in 1974. In old Japan, it had been a common custom for people of high cultural standing to write a poem before death. On Kunichika's grave his poem reads:

"Since I am tired of painting portraits of people of this world, I will paint portraits of the King of hell and the devils."

Yo no naka no, hito no nigao mo akitareba, enma ya oni no ikiutsushisemu.[30]

Legacy

In 1915, Arthur Davison Ficke, an Iowa lawyer, poet, and influential collector of Japanese prints, wrote Chats on Japanese Prints. In the book he listed fifty-five artists, including Kunichika, whose work he dismissed as "degenerate" and as "All that meaningless complexity of design, coarseness of color and carelessness of printing that we associate with the final ruin of the art of color prints."[31] His opinion, which differed from that of Kunichika's contemporaries, influenced American collectors for many years, with the result that Japanese prints produced in the second half of the 19th century, especially figure prints, fell out of favor.[32][33]

In the late 1920s and early 1930s an author, adventurer, banker and great collector of Japanese art, Kojima Usui, wrote many articles aimed at resurrecting Kunichika's reputation. He was not successful in his day, but his work became a basis for later research, which did not really begin until quite recently.[34][35] In 1876 Laurance P. Roberts wrote in his Dictionary of Japanese Artists that Kunichika produced prints of actors and other subjects in the late Kunisada tradition, reflecting the declining taste of the Japanese and the deterioration of color printing. Roberts described him as, "A minor artist, but represents the last of the great ukiyo-e tradition." The cited biography reflects the author's preference for classical ukiyo-e. Richard A. Waldman, owner of The Art of Japan, said of Roberts's view, "Articles such as the above and others by early western authors managed to put this artist in the dustbin of art history."[36] An influential reason for Kunichika's return to favor in the western world is the publication, in 1999, in English, of Amy Reigle Newland's Time present and time past: Images of a forgotten master: Toyohara Kunichika 1835–1900.[37] [38] In addition, the 2008 show at the Brooklyn Museum, Utagawa: Masters of the Japanese Print, 1770–1900, and a resulting article in The New York Times of 03/22/08[39] have increased public awareness of and prices for Kunichika prints.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Newland, pp. 7–16

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Newland p 7

- ↑ Hinkel, p 70

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hinkel, p 74

- ↑ Aragorô, Shôriya. "Oshie Series: Kagekiyo". Kabuki 21. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- ↑ Newland, pp 7-8

- ↑ Fiorillo, John. "Utagawa Kunisada (1786–1865)". Viewing Japanese Prints. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Newland p 11

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Newland p 12

- ↑ Newland, pp 17-22

- ↑ Newland, p 8

- ↑ Newland, pp 17, 35

- ↑ Hinkel, p 77

- ↑ Newland, pp 21, 22, 28

- ↑ Newland, p 23

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Castle, Frank. "Kunichika (1835–1900)". Artists' Bios. Castle Fine Arts. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ↑ Hinkel, p 78

- ↑ Newland, p 19

- ↑ Faulkner pp 32, 34, 35

- ↑ Manuel Paias. "Man-Pai / Room 2: Kunichika". A list of the main series of some of the most important artists of Japanese Woodblock Prints. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ↑ Newland, p 30

- ↑ Newland, pp 30-31

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Hinkel, p 71

- ↑ Newland, p 14

- ↑ Newland, pp 14-16

- ↑ "Kunichika Toyohara – 1835–1900". Biography of Japanese print artist Kunichika Toyohara. artelino. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ↑ Newland, p 15

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Hinkel p 72

- ↑ "Kunichika Toyohara — 1835–1900". Oe Naokichi Collection of Toyohara Kunichika's Ukiyo-e prints at the Kyoto University of Art and Design Collection. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ↑ Newland, p 16

- ↑ Ficke, pp 351–353

- ↑ Bozulich, Richard. "Japanese Prints and the World of Go". Kiseido. Archived from the original on March 16, 2008. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ↑ Brown, p 13

- ↑ Newland p 38

- ↑ Fujii, Lucy Birmingham. "World of Kojima Usui Collection". Metropolis. Archived from the original on May 7, 2008. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ↑ Waldman, Richard A. "Kunichika Toyohara (1835–1900)". The Art of Japan. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ↑ "New Books". University of Michigan. Archived from the original on January 25, 2008. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ↑ "Hanshan Tang Books — List 144: New Publications; Recent Works on Chinese Ceramics; Latest Acquisitions" (PDF). Hanshan Tang Books Ltd. p. 52. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ↑ Johnson, Ken (March 22, 2008). "Fleeting Pleasures of Life in Vibrant Woodcut Prints". The New York Times. p. 289.

References

- Brown, Kendall; Green, Nancy; Stevens, Andrew (2006). Color Woodcut International: Japan, Britain and America in the Early Twentieth Century. Madison, WI, U.S.A.: Chazen Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison. ISBN 978-0-932900-64-7.

- "Castle Fine Arts Biography: Kunichika (1835–1900)". Castle fine arts. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- Faulkner, Rupert (1999). Masterpieces of Japanese Prints: Ukiyo-e from the Victoria and Albert Museum. Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha International Ltd. ISBN 978-4-7700-2387-2.

- Ficke, Arthur Davidson (1915). "Chats on Japanese Prints". London, England: T. Unwin Ltd.

- Hinkel, Monika (2006). "Toyohara Kunichika (1835–1900)". Doctoral Dissertation (in German). Bonn, Universität Bonn. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 7, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- Newland, Amy Reigle (1999). Time present and time past: Images of a forgotten master: Toyohara Kunichika, 1835–1900. Leyden, the Netherlands: Hotei Publishing. ISBN 978-90-74822-11-4.

At this time this is the only substantive reference written in English. All other sources cite this one. The book consists of "Toyohara Kunichika: His life and personality," pp 7–16; "Aspects of Kunichika's art: Images of beauties and actors," pp 17–29; "Kunichika's legacy," pp 30–32; footnotes, pp 33–38; "Kawanabe Kyosai and Toyohara Kunichika," an essay by Shigeru Oikawa, pp 39–49. The remainder of the book, pp 50–154, is an illustrated catalog of 133 of the prints; an appendix on signatures and seals, pp 155–164; a glossary, pp 165–167.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kunichika Toyohara. |

Biography

- Kunichika's biography

- Oe Naokichi Collection of Toyohara Kunichika's Ukiyo-e prints at the Kyoto University of Art and Design collection.

Looking at Kunichika

Museum Sites

Image Sources

- Castle fine arts

- Japan Print Gallery

- Man-Pai / Japanese Prints

- Ohmi Gallery: Ukiyo-e and Shin Hanga prints from the collection of Dr Ross Walker

- Robyn Buntin of Honolulu

- Tokugawa Gallery

- Toyohara Kunichika (1835–1900) Bildband

|