Toroidal coordinates

Toroidal coordinates are a three-dimensional orthogonal coordinate system that results from rotating the two-dimensional bipolar coordinate system about the axis that separates its two foci. Thus, the two foci  and

and  in bipolar coordinates become a ring of radius

in bipolar coordinates become a ring of radius  in the

in the  plane of the toroidal coordinate system; the

plane of the toroidal coordinate system; the  -axis is the axis of rotation. The focal ring is also known as the reference circle.

-axis is the axis of rotation. The focal ring is also known as the reference circle.

Definition

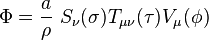

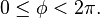

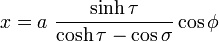

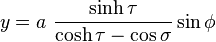

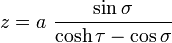

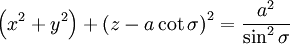

The most common definition of toroidal coordinates  is

is

where the  coordinate of a point

coordinate of a point  equals the angle

equals the angle  and the

and the  coordinate equals the natural logarithm of the ratio of the distances

coordinate equals the natural logarithm of the ratio of the distances  and

and  to opposite sides of the focal ring

to opposite sides of the focal ring

The coordinate ranges are  and

and  and

and

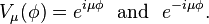

Coordinate surfaces

Surfaces of constant  correspond to spheres of different radii

correspond to spheres of different radii

that all pass through the focal ring but are not concentric. The surfaces of constant  are non-intersecting tori of different radii

are non-intersecting tori of different radii

that surround the focal ring. The centers of the constant- spheres lie along the

spheres lie along the  -axis, whereas the constant-

-axis, whereas the constant- tori are centered in the

tori are centered in the  plane.

plane.

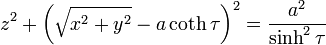

Inverse transformation

The (σ, τ, φ) coordinates may be calculated from the Cartesian coordinates (x, y, z) as follows. The azimuthal angle φ is given by the formula

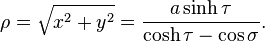

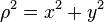

The cylindrical radius ρ of the point P is given by

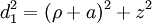

and its distances to the foci in the plane defined by φ is given by

The coordinate τ equals the natural logarithm of the focal distances

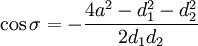

whereas the coordinate σ equals the angle between the rays to the foci, which may be determined from the law of cosines

where the sign of σ is determined by whether the coordinate surface sphere is above or below the x-y plane.

Scale factors

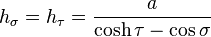

The scale factors for the toroidal coordinates  and

and  are equal

are equal

whereas the azimuthal scale factor equals

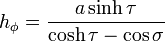

Thus, the infinitesimal volume element equals

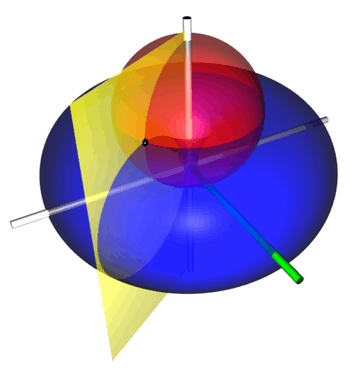

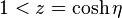

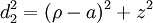

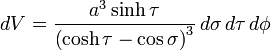

and the Laplacian is given by

Other differential operators such as  and

and  can be expressed in the coordinates

can be expressed in the coordinates  by substituting

the scale factors into the general formulae

found in orthogonal coordinates.

by substituting

the scale factors into the general formulae

found in orthogonal coordinates.

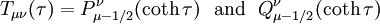

Toroidal harmonics

Standard separation

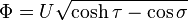

The 3-variable Laplace equation

admits solution via separation of variables in toroidal coordinates. Making the substitution

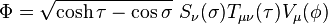

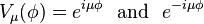

A separable equation is then obtained. A particular solution obtained by separation of variables is:

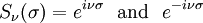

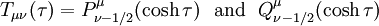

where each function is a linear combination of:

Where P and Q are associated Legendre functions of the first and second kind. These Legendre functions are often referred to as toroidal harmonics.

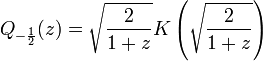

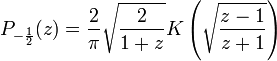

Toroidal harmonics have many interesting properties. If you make a variable substitution  then, for instance, with vanishing order (the convention is to not write the order when it vanishes) and

then, for instance, with vanishing order (the convention is to not write the order when it vanishes) and

and

where  and

and  are the complete elliptic integrals of the first and second kind respectively. The rest of the toroidal harmonics can be obtained, for instance, in terms of the complete elliptic integrals, by using recurrence relations for associated Legendre functions.

are the complete elliptic integrals of the first and second kind respectively. The rest of the toroidal harmonics can be obtained, for instance, in terms of the complete elliptic integrals, by using recurrence relations for associated Legendre functions.

The classic applications of toroidal coordinates are in solving partial differential equations, e.g., Laplace's equation for which toroidal coordinates allow a separation of variables or the Helmholtz equation, for which toroidal coordinates do not allow a separation of variables. Typical examples would be the electric potential and electric field of a conducting torus, or in the degenerate case, an electric current-ring (Hulme 1982).

An alternative separation

Alternatively, a different substitution may be made (Andrews 2006)

where

Again, a separable equation is obtained. A particular solution obtained by separation of variables is then:

where each function is a linear combination of:

Note that although the toroidal harmonics are used again for the T function, the argument is  rather than

rather than  and the

and the  and

and  indices are exchanged. This method is useful for situations in which the boundary conditions are independent of the spherical angle

indices are exchanged. This method is useful for situations in which the boundary conditions are independent of the spherical angle  , such as the charged ring, an infinite half plane, or two parallel planes. For identities relating the toroidal harmonics with argument hyperbolic

cosine with those of argument hyperbolic cotangent, see the Whipple formulae.

, such as the charged ring, an infinite half plane, or two parallel planes. For identities relating the toroidal harmonics with argument hyperbolic

cosine with those of argument hyperbolic cotangent, see the Whipple formulae.

References

- Byerly, W E. (1893) An elementary treatise on Fourier's series and spherical, cylindrical, and ellipsoidal harmonics, with applications to problems in mathematical physics Ginn & co. pp. 264–266

- Arfken G (1970). Mathematical Methods for Physicists (2nd ed.). Orlando, FL: Academic Press. pp. 112–115.

- Andrews, Mark (2006). "Alternative separation of Laplace's equation in toroidal coordinates and its application to electrostatics". Journal of Electrostatics 64 (10): 664–672. doi:10.1016/j.elstat.2005.11.005.

- Hulme, A. (1982). "A note on the magnetic scalar potential of an electric current-ring". Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 92 (01): 183–191. doi:10.1017/S0305004100059831.

Bibliography

- Morse P M, Feshbach H (1953). Methods of Theoretical Physics, Part I. New York: McGraw–Hill. p. 666.

- Korn G A, Korn T M (1961). Mathematical Handbook for Scientists and Engineers. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 182. LCCN 59014456.

- Margenau H, Murphy G M (1956). The Mathematics of Physics and Chemistry. New York: D. van Nostrand. pp. 190–192. LCCN 55010911.

- Moon P H, Spencer D E (1988). "Toroidal Coordinates (η, θ, ψ)". Field Theory Handbook, Including Coordinate Systems, Differential Equations, and Their Solutions (2nd ed., 3rd revised printing ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. pp. 112–115 (Section IV, E4Ry). ISBN 0-387-02732-7.

External links

| ||||||||||

![\begin{align}

\nabla^2 \Phi =

\frac{\left( \cosh \tau - \cos\sigma \right)^{3}}{a^{2}\sinh \tau}

& \left[

\sinh \tau

\frac{\partial}{\partial \sigma}

\left( \frac{1}{\cosh \tau - \cos\sigma}

\frac{\partial \Phi}{\partial \sigma}

\right) \right. \\[8pt]

& {} \quad +

\left. \frac{\partial}{\partial \tau}

\left( \frac{\sinh \tau}{\cosh \tau - \cos\sigma}

\frac{\partial \Phi}{\partial \tau}

\right) +

\frac{1}{\sinh \tau \left( \cosh \tau - \cos\sigma \right)}

\frac{\partial^2 \Phi}{\partial \phi^2}

\right]

\end{align}](../I/m/68f83261c7c0f32857bdfb87a65a500f.png)