Tornado records

This article lists various tornado records. The most extreme tornado in recorded history was the Tri-State Tornado, which roared through parts of Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana on March 18, 1925. It is considered an F5, though tornadoes were not ranked on any scale in that era. It holds records for longest path length at 219 mi (352 km), longest duration at about 3.5 hours, and fastest forward speed for a significant tornado at 73 mph (117 km/h) anywhere on Earth. In addition, it is the deadliest single tornado in United States history (695 dead).[1] It was also the second costliest tornado in history at the time, but has been surpassed by several others non-normalized. When costs are normalized for wealth and inflation, it still ranks third today.[2]

The deadliest tornado in world history was the Daulatpur–Saturia tornado in Bangladesh on April 26, 1989, which killed approximately 1,300 people.[3] Bangladesh has had at least 19 tornadoes in its history kill more than 100 people, almost half of the total for the rest of the world.

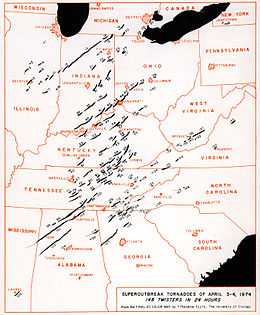

For 37 years, the most extensive tornado outbreak on record, in almost every category, was the Super Outbreak, which affected a large area of the central United States and extreme southern Ontario in Canada on April 3 and April 4, 1974. Not only did this outbreak feature an incredible 148 tornadoes in only 18 hours, but an unprecedented number of them were violent; 7 were of F5 intensity and 23 were F4. This outbreak had a staggering 16 tornadoes on the ground at the same time at the peak of the outbreak. More than 300 people, possibly as many as 330, were killed by tornadoes during this outbreak. However, this record was later broken during the April 25–28, 2011 tornado outbreak, which resulted in 355 tornadoes and 324 tornadic fatalities.[4]

Tornado outbreaks

Most tornadoes in single 24-hour period

The April 25–28, 2011 tornado outbreak was the most prolific tornado outbreak in U.S. history. It produced 355 tornadoes, with 211 of those in a single 24-hour period on April 27,[5] including 11 EF4 and 4 EF5 tornadoes. 348 deaths occurred in that outbreak, of which 324 were tornado related. The outbreak helped smash the record for most tornadoes in the month of April with 765 tornadoes, almost triple the prior record (267 in April 1974). The overall record for a single month was 542 in May 2003, which was also broken.[6]

The infamous Super Outbreak of April 3–4, 1974, which spawned 148 confirmed tornadoes across eastern North America, held the record for the most prolific tornado outbreak for many years. Not only did it produce an exceptional number of tornadoes, but it was also an inordinately intense outbreak producing dozens of large, long-track tornadoes, including 7 F5 and 23 F4 tornadoes. More significant tornadoes occurred within 24 hours than any other week in the tornado record.[7] Due to a secular trend in tornado reporting, the 2011 and 1974 tornado counts are not directly comparable.

Longest continuous outbreak and largest autumnal outbreak

Most tornado outbreaks in North America occur in the spring, but there is a secondary peak of tornado activity in the fall which is less consistent but can include exceptionally large and/or intense outbreaks. In 1992, an estimated 95 tornadoes broke out in a record 41 hours of continuous tornado activity from November 21 to 23. This is also among the largest known outbreaks in areal expanse. Many other very large outbreaks have occurred in autumn, especially in October and November.[1]

Greatest number of tornadoes spawned from a hurricane

The greatest number of tornadoes spawned from a hurricane is 118 from Hurricane Ivan in 2004.[8] Caution is advised comparing the raw number of counted tornadoes from recent decades to decades prior to the 1990s since more tornadoes that occur are now recorded than in the past.

Tornado casualties and damage

| 10 deadliest Canadian tornadoes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name (location) | Date | Deaths | |

| 1 | Regina Cyclone | June 30, 1912 | ≥28 | |

| 2 | Edmonton tornado | July 31, 1987 | 27 | |

| 3 | Windsor–Tecumseh, Ontario tornado | June 17, 1946 | 17 | |

| 4 | Pine Lake, Alberta tornado | July 14, 2000 | 12 | |

| =5 | Salaberry-de-Valleyfield, Quebec Windsor, Ontario tornado |

August 16, 1888 April 3, 1974 |

9 9 | |

| 7 | Barrie, Ontario tornado | May 31, 1985 | 8 | |

| =8 | Sudbury, Ontario tornado Sainte-Rose, Quebec tornado |

August 20, 1970 June 8, 1953 |

6 6 | |

| =10 | Bouctouche, New Brunswick tornado Portage la Prairie, Manitoba tornado |

August 6, 1879 June 22, 1922 |

5 5 | |

| Sources: Environment Canada (PDF) | ||||

| 10 deadliest American tornadoes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name (location) | Date | Deaths | |

| 1 | "Tri-State" (Missouri, Illinois and Indiana) | March 18, 1925 | 695 | |

| 2 | Natchez, Mississippi | May 7, 1840 | 317 | |

| 3 | St. Louis, Missouri and East St. Louis, Illinois | May 27, 1896 | 255 | |

| 4 | Tupelo, Mississippi | April 5, 1936 | 216 | |

| 5 | Gainesville, Georgia | April 5, 1936 | 203 | |

| 6 | Woodward, Oklahoma | April 9, 1947 | 181 | |

| 7 | Joplin, Missouri | May 22, 2011 | 158 | |

| 8 | Amite, Louisiana and Purvis, Mississippi | April 24, 1908 | 143 | |

| 9 | New Richmond, Wisconsin | June 12, 1899 | 117 | |

| 10 | Flint, Michigan |

June 8, 1953 |

116 | |

| Source: Storm Prediction Center | ||||

| 25 deadliest US tornadoes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name (location) | Date | Deaths | |

| 1 | "Tri-State" (Missouri, Illinois and Indiana) | March 18, 1925 | 695 | |

| 2 | Natchez, Mississippi | May 6, 1840 | 317 | |

| 3 | St. Louis, Missouri and East St. Louis, Illinois | May 27, 1896 | 255 | |

| 4 | Tupelo, Mississippi | April 5, 1936 | 216 | |

| 5 | Gainesville, Georgia | April 6, 1936 | 203 | |

| 6 | Woodward, Oklahoma | April 9, 1947 | 181 | |

| 7 | Joplin, Missouri | May 22, 2011 | 162 | |

| 8 | Amite, Louisiana and Purvis, Mississippi | April 24, 1908 | 143 | |

| 9 | New Richmond, Wisconsin | June 12, 1899 | 117 | |

| 10 | Flint, Michigan |

June 8, 1953 |

116 | |

| 11 - - - |

Waco, Texas Goliad, Texas |

May 11, 1953 May 18, 1902 |

114 114 | |

| 13 | Omaha, Nebraska | March 23, 1913 | 103 | |

| 14 | Mattoon, Illinois | May 26, 1917 | 101 | |

| 15 | Shinnston, West Virginia | June 23, 1944 | 100 | |

| 16 | Marshfield, Missouri | April 18, 1880 | 99 | |

| 17 - - - |

Gainesville and Holland, Georgia Poplar Bluff, Missouri |

June 1, 1903 May 9, 1927 |

98 98 | |

| 19 | Snyder, Oklahoma | May 10, 1905 | 97 | |

| 20 | Worcester, Massachusetts | June 9, 1953 | 94 | |

| 21 | Camanche, Iowa | June 3, 1860 | 92 | |

| 22 | Natchez, Mississippi | April 24, 1908 | 91 | |

| 23 | Starkville, Mississippi and Waco, Alabama | April 20, 1920 | 88 | |

| 24 | Lorain and Sandusky, Ohio | June 28, 1924 | 85 | |

| 25 | Udall, Kansas | May 25, 1955 | 80 | |

| Sources: Storm Prediction Center: The 25 Deadliest U.S. Tornadoes, SPC Annual U.S. Killer Tornado Statistics, Tornado Project | ||||

| 10 costliest US tornadoes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Area affected | Date | Damage 1 | Adjusted Damage 2 |

| 1 | Joplin, Missouri | May 22, 2011 | 2800 | 2935 |

| 2 | Tuscaloosa, Alabama | April 27, 2011 | 2450 | 2569 |

| 3 | Moore, Oklahoma | May 20, 2013 | 2000 | 2025 |

| 4 | Oklahoma City Metro, Oklahoma | May 3, 1999 | 1000 | 1415 |

| 5 | Hackleburg, Alabama | April 27, 2011 | 1290 | 1352 |

| 6 | Wichita Falls, Texas | April 10, 1979 | 400 | 1299 |

| 7 | Omaha, Nebraska | May 6, 1975 | 250 | 1094 |

| 8 | Washington, Illinois | November 17, 2013 | 935 | 947 |

| 9 | Lubbock, Texas | May 11, 1970 | 250 | 820 |

| 10 | Topeka, Kansas | June 8, 1966 | 250 | 726 |

| Source: Brooks, Harold E.; C. A. Doswell (Feb 2001). "Normalized Damage from Major Tornadoes in the United States: 1890–1999". Weather and Forecasting (American Meteorological Society) 16 (1): 168–76. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(2001)016<0168:NDFMTI>2.0.CO;2. 3 | ||||

|

1. These are the unadjusted damage totals in millions of US dollars. | ||||

| Deadliest tornadoes by state | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Location | Date | Deaths | |

| Alabama | Many towns | April 27, 2011 | 72 | |

| Alaska | - | No deadly tornadoes | - | |

| Arizona | San Xavier Mission Indian Village | August 27, 1964 | 2 | |

| Arkansas | Fort Smith Warren |

January 11, 1898 January 3, 1949 |

55 | |

| California | - | No deadly tornadoes | - | |

| Colorado | Thurman | August 10, 1924 | 10 | |

| Connecticut | Wallingford | August 9, 1878 | 34 | |

| Delaware | Hartly | July 21, 1983 | 2 | |

| Florida | Kissimmee | February 22, 1998 | 25 | |

| Georgia | Gainesville | April 6, 1936 | 203 | |

| Hawaii | - | No deadly tornadoes | - | |

| Idaho | Ruebens | June 7, 1936 | 2 | |

| Illinois | Many towns | March 18, 1925 | 613 | |

| Indiana | Many towns | March 18, 1925 | 71 | |

| Iowa | Dewitt/Camanche | June 3, 1860 | 92 | |

| Kansas | Udall | May 25, 1955 | 82 | |

| Kentucky | Louisville | March 27, 1890 | 76 | |

| Louisiana | Gilliam | May 13, 1908 | 49 | |

| Maine | Caribou | August 11, 1954 | 1* | |

| Maryland | La Plata | November 9, 1926 | 16 | |

| Massachusetts | Worcester | June 9, 1953 | 94 | |

| Michigan | Flint | June 8, 1953 | 115 | |

| Minnesota | St. Cloud/Sauk Rapids | April 14, 1886 | 72 | |

| Mississippi | Natchez | May 7, 1840 | 317 | |

| Missouri | Joplin | May 22, 2011 | 158 | |

| Montana | Reserve | July 26, 2010 | 2* | |

| Nebraska | Omaha | March 23, 1913 | 101 | |

| Nevada | - | No deadly tornadoes | - | |

| New Hampshire | Corydon | September 9, 1821 | 6 | |

| New Jersey | New Brunswick | June 19, 1835 | 5 | |

| New Mexico | Wagon Mound | May 31, 1930 | 2 | |

| New York | Smithfield | July 8, 2014 | 4 | |

| North Carolina | Philadelphia | February 19, 1884 | 23 | |

| North Dakota | Fargo | June 20, 1957 | 10 | |

| Ohio | Lorain/Sandusky | June 28, 1924 | 85 | |

| Oklahoma | Woodward | April 9, 1947 | 113 | |

| Oregon | Long Creek | June 3, 1894 | 3* | |

| Pennsylvania | Many towns | June 23, 1944 | 26 | |

| Rhode Island | - | No deadly tornadoes | - | |

| South Carolina | Aiken/Timmonsville | April 30, 1924 | 53 | |

| South Dakota | Wilmot | June 17, 1944 | 8 | |

| Tennessee | Henderson | March 21, 1952 | 38 | |

| Texas | Goliad Waco |

May 18, 1902 May 11, 1953 |

114 | |

| Utah | Salt Lake City | August 11, 1999 | 1 | |

| Vermont | - | No deadly tornadoes | - | |

| Virginia | Scott County | May 2, 1929 | 13 | |

| Washington | Vancouver | April 5, 1972 | 6 | |

| West Virginia | Many towns | June 23, 1944 | 100 | |

| Wisconsin | New Richmond | June 12, 1899 | 117 | |

| Wyoming | Wheatland | June 25, 1942 | 2 | |

| Source: Tornado Project | ||||

| *Most recent tornado with this number of deaths | ||||

Deadliest single tornado in world history

On April 26, 1989 in Bangladesh a massive tornado took at least 1,300 lives.[9]

Deadliest single tornado in US history

The Tri-State Tornado of March 18, 1925 killed 695 people in Missouri (11), Illinois (613), and Indiana (71). The outbreak it occurred with was also the deadliest known tornado outbreak, with a combined death toll of 747 across the Mississippi River Valley.[1][10][11]

Most damaging tornado

Similar to fatalities, damage (and observations) of a tornado are a coincidence of what character of tornado interacts with certain characteristics of built up areas. That is, destructive tornadoes are in a sense "accidents" of a large tornado striking a large population. In addition to population and changes thereof, comparing damage historically is subject to changes in wealth and inflation. The 1896 St. Louis–East St. Louis tornado on May 27, incurred the most damages adjusted for wealth and inflation, at an estimated $2.9 billion (1997 USD). In raw numbers, the Joplin tornado of May 22, 2011 is considered the costliest tornado in recent history, with damage totals near $2.8 billion (2011 USD). Until 2011, the "Oklahoma City tornado" of May 3, 1999 was the most damaging.[12]

Largest and most powerful tornadoes

Highest winds observed in a tornado

During the F5 1999 Bridge Creek–Moore tornado on May 3, 1999, a Doppler on Wheels situated near the tornado measured winds of 301 ± 20 mph (484 ± 32 km/h) momentarily in a small area inside the funnel approximately 100 m (330 ft) above ground level.[13]

On May 31, 2013, a tornado hit rural areas near El Reno, Oklahoma. The tornado was originally rated as an EF3 based on damage; however, after mobile radar data analysis was conducted, it was concluded to have an EF5 due to a measured wind speed of greater than 296 mph (476 kmh), second only to the Bridge Creek - Moore tornado. Revised RaXPol analysis found winds of 302 mph (486 km/h) well above ground level and ≥291 mph (468 km/h) below 10 m (33 ft) with some subvortices moving at 175 mph (282 km/h).[14] These winds may possibly be as high or higher than the winds recorded on May 3, 1999. Despite the recorded windspeed, the El Reno tornado was later downgraded back to EF3 due to the fact that no EF5 damage was found, likely due to the lack of sufficient damage indicators.[15][16]

Winds were measured at 257–268 mph (414–431 km/h) using portable Doppler radar in the Red Rock, Oklahoma tornado during the April 26, 1991 tornado outbreak. Though these winds are possibly indicative of an F5 strength tornado, this particular tornado's path never encountered any significant structures and caused minimal damage. Thus it was rated an F4.[17]

Longest damage path and duration

The longest known track for a single tornado is the Tri-State Tornado with a path length of 151 to 235 mi (243 to 378 km). For years there was debate whether the originally recognized path length of 219 mi (352 km) over 3.5 hours was from one tornado or a series. Some very long track (VLT) tornadoes were later determined to be successive tornadoes spawned by the same supercell thunderstorm, which are known as a tornado family. The Tri-State Tornado, however, appeared to have no gaps in the damage. A six year reanalysis study by a team of severe convective storm meteorologists found insufficient evidence to make firm conclusions but does conclude that it is likely that the beginning and ending of the path was resultant of separate tornadoes comprising a tornado family. It also found that the tornado began 15 mi (24 km) to the west and ended 1 mi (1.6 km) farther east than previously known, bringing the total path to 235 mi (378 km). The 174 mi (280 km) segment from central Madison County, Missouri to Pike County, Indiana is likely one continuous tornado and the 151 mi (243 km) segment from central Bollinger County, Missouri to western Pike County, Indiana is very likely a single continuous tornado. Another significant tornado was found about 65 mi (105 km) east-northeast of the end of aforementioned segment(s) of the Tri-State Tornado Family and is likely another member of the family. Its path length of 20 mi (32 km) over about 20 min makes the known tornado family path length total to 320 mi (510 km) over about 5.5 hours[18] Grazulis in 2001 wrote that the first 60 mi (97 km) of the (originally recognized) track is probably the result of two or more tornadoes and that a path length of 157 mi (253 km) was seemingly continuous.[19]

Longest path and duration tornado family

What at one time was thought to be the record holder for the longest tornado path is now thought to be the longest tornado family, with a track of at least 293 miles (472 km) on May 26, 1917 from the Missouri border across Illinois into Indiana. It caused severe damage and mass casualties in Charleston and Mattoon, Illinois.[1]

What was probably the longest track supercell thunderstorm tracked 790 miles (1,270 km) across 6 states in 17.5 hours on March 12, 2006 as part of the March 2006 tornado outbreak sequence. It began in Noble County, Oklahoma and ended in Jackson County, Michigan, producing many tornadoes in Missouri and Illinois.[20]

Largest path width

Officially, the widest tornado on record is the El Reno, Oklahoma tornado of May 31, 2013 with a width of 2.6 miles (4.2 km) at its peak. This is the width found by the National Weather Service based on preliminary data from University of Oklahoma RaxPol mobile radar that also sampled winds of 296 mph (476 km/h) which was used to upgrade the tornado to EF5.[21] However, it was revealed that these winds did not impact any structures, and as a result the tornado was downgraded to EF3 based on damage.[22] However, another possible contender for the widest tornado as measured by radar was the F4 Mulhall tornado in north-central Oklahoma which occurred during the 1999 Oklahoma tornado outbreak. The diameter of the maximum winds (over 110 mph (49 m/s)) was over 5,200 feet (1,600 m) as measured by a DOW radar. Although the tornado passed largely over rural terrain, the width of the wind swath capable of producing damage was as wide as 4 mi (6.4 km).[23][24]

The F4 Hallam, Nebraska tornado during the outbreak of May 22, 2004 was the previous official record holder for the widest tornado, surveyed at 2.5 miles (4.0 km) wide. A similar size tornado struck Edmonson, Texas on May 31, 1968, when a damage path width between 2 to 3 miles (3.2 to 4.8 km) was recorded from an F3 tornado.[25]

Highest forward speed

73 miles per hour (117 km/h) from the Tri-State Tornado (other weak tornadoes have approached or exceeded this speed, but this is the fastest forward movement observed in a major tornado).[1]

Greatest pressure drop

A pressure deficit of 100 millibars (2.95 inHg) was observed when a violent tornado near Manchester, South Dakota on June 24, 2003 passed directly over an in-situ probe that storm chasing researcher Tim Samaras deployed.[26] In less than a minute, the pressure dropped to 850 millibars (25.10 inHg), which are the greatest pressure decline and the lowest pressure ever recorded at the Earth's surface when adjusted to sea level.[27][28]

On April 21, 2007, a 194-millibar (5.73 inHg) pressure deficit was reported when a tornado struck a storm chasing vehicle in Tulia, Texas.[29] The tornado caused EF2 damage as it passed through Tulia. The reported pressure drop far exceeds that which would be expected based on theoretical calculations.[30]

There is a questionable and unofficial citizen's barometer measurement of a 192-millibar (5.67 inHg) drop around Minneapolis in 1904.[31]

Early tornadoes

Earliest known tornado in Europe

- The earliest recorded tornado in Europe struck Rosdalla, near Kilbeggan, Ireland on April 30, 1054. The earliest known British tornado hit central London on October 23, 1091 and was especially destructive.[32]

Earliest known tornado in the Americas

- An apparent tornado is recorded to have struck Tlatelolco (present day Mexico City), on August 21, 1521, two days before the Aztec capital's fall to Cortés. Many other tornadoes are documented historically within the Basin of Mexico.[33]

First confirmed tornado and first tornado fatality in present-day United States

- August 1671 - Rehoboth, Massachusetts[34][35]

- July 8, 1680 - Cambridge, Massachusetts - 1 dead[1][36]

Exceptional tornado droughts

Longest span without a tornado rated F5 or EF5

Before the Greensburg EF5 tornado on May 4, 2007, it had been 8 years and one day since the US had had a confirmed F5 or EF5 tornado. The last confirmed F5 or EF5 hit southern Oklahoma City and surrounding communities during the May 3, 1999 event. This is the longest interval without an F5 or EF5 tornado since official records began in 1950.

Exceptional survivors

Longest distance carried by a tornado

Matt Suter of Fordland, Missouri holds the record for the longest-known distance traveled by anyone picked up by a tornado who lived to tell about it. On March 12, 2006 he was carried 1,307 feet (398 m), 13 feet (4.0 m) shy of one-quarter mile (400 m), according to National Weather Service measurements.[37][38]

Exceptional coincidences

Codell, Kansas

The small town of Codell, Kansas, was hit by a tornado on the same date (May 20) three consecutive years: 1916, 1917, and 1918.[39][40] The U.S. has about 100,000 thunderstorms a year; less than one percent produce a tornado. The odds of this coincidence occurring again is extremely small.

Tanner/Harvest, Alabama

Tanner, a small town in northern Alabama, was hit by an F5 tornado on April 3, 1974 and was struck again 45 minutes later by a second F5 (however the rating is disputed and it may have been high-end F4), demolishing what remained of the town. 37 years later, on April 27, 2011 (the largest and deadliest outbreak since 1974), Tanner was hit yet again by the EF5 2011 Hackleburg–Phil Campbell, Alabama tornado, which produced high-end EF4 damage in the southern portion of town. The suburban community of Harvest, Alabama, just to the north, also sustained major impacts from all three Tanner tornadoes, and was also hit by destructive tornadoes in 1995 and 2012.

Moore, Oklahoma

The Oklahoma City suburb of Moore was hit by devastating tornadoes in 1973, 1999, 2003, 2010, and 2013, five of which were of F4/EF4 strength or greater, although it was determined that the tornado in 2003 caused no F4 damage within Moore itself, but in areas to its northeast. The 1999 and 2013 events were rated F5 and EF5, respectively. In total, about 20 tornadoes have struck within the immediate vicinity of Moore since 1890, the most recent of which was an EF2 on March 25, 2015.[41]

Tuscaloosa, Alabama

The college town of Tuscaloosa, Alabama was directly hit by killer tornadoes in 1932, 1975, 1997, 2000, and 2011, all but one of which were rated F4 or EF4 (the 1997 tornado was rated F2). The 2011 tornado went on to devastate parts of Birmingham, Alabama.

Birmingham, Alabama

The northwestern suburbs of Birmingham, Alabama have been devastated by violent and deadly tornadoes in 1954, 1977, 1998, and 2011. The 1977 and 1998 tornadoes were rated F5, and the 1954 and 2011 tornadoes were rated F4 and EF4. The suburb of McDonald Chapel was hit directly by the 1956, 1998, and 2011 tornadoes.

St. Louis, Missouri

Throughout history, the Greater St. Louis area has been hit by destructive and deadly tornado numerous times, most notably in 1871, 1896, 1927, 1959, 1967, and 2011. The 1896 tornado killed 255 people, and was the third deadliest in American history, and the 1896 tornado was the costliest whereas as the 1927 tornado was the second costliest (adjusted for inflation and increasing population). Additionally, the first and second most costly hailstorms also struck St. Louis on 10 April 2001 and 28 April 2012, respectively, with the former causing more damage in real dollars than the 1999 Oklahoma City tornado did.

McConnell AFB/Haysville, Kansas

The southern portions of the Wichita, KS Metropolitan Statistical Area, particularly the suburb of Haysville and nearby McConnell Air Force Base, have been hit by destructive tornadoes in 1991, 1999, and 2012. A violent tornado on April 26, 1991 went on to strike nearby Andover at F5 strength, killing 17 people. Remarkably, an F3 tornado followed a very similar path through the area the next month, causing an additional $1,000,000 in damage. The EF3 2012 tornado followed a path that was almost identical to both of the 1991 tornadoes.

Jackson, Tennessee

The city of Jackson, Tennessee has been hit by an F4/EF4 tornado three separate times, in 1999, 2003, and 2008. Interestingly, all three of these tornadoes occurred after dark and were preceded or followed by a separate F3/EF3 tornado that caused additional destruction in the Jackson area.

See also

- Weather records

- List of tropical cyclone extremes

- Tornado myths

- List of F5 and EF5 tornadoes

- List of tornadoes and tornado outbreaks

- List of tornado-related deaths at schools

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Grazulis, Thomas P. (July 1993). Significant Tornadoes 1680–1991: A Chronology and Analysis of Events. St. Johnsbury, VT: The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. ISBN 1-879362-03-1.

- ↑ Brooks, Harold E.; Doswell, Charles A, III (September 2000). "Normalized Damage from Major Tornadoes in the United States: 1890–1999". Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- ↑ Paul, Bhuiyan (2004). "The April 2004 Tornado in North-Central Bangladesh: A Case for Introducing Tornado Forecasting and Warning Systems" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-08-17.

- ↑ Hoxit, Lee R; Chappell, Charles F (October 1975). "Tornado Outbreak of April 3–4, 1974; Synoptic Analysis" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2007-03-02.

- ↑ http://wmo.asu.edu/tornado-largest-tornado-outbreak

- ↑ "April 2011 tornado information". NOAA. Retrieved 2011-05-03.

- ↑ Schneider, Russell; H.E. Brooks, J.T. Schaefer (October 2004). "Tornado Outbreak Day Sequences: historic events and climatology (1875-2003)". 22nd Conf Severe Local Storms. Hyannis, MA: American Meteorological Society.

- ↑ Edwards, Roger (2012). "Tropical Cyclone Tornadoes: A Review of Knowledge in Research and Prediction" (PDF). E-Journal of Severe Storms Meteorology 7 (6): 3. Retrieved 2013-05-22.

- ↑ Grazulis, Tom (2000). "Tornadoes in Bangladesh". Worldwide Tornadoes. The Tornado Project.

- ↑ Tornado Facts for Kids - Tornado Information for Students and Kids

- ↑ Tri-State Tornado information, facts and history.

- ↑ Brooks, Harold E.; Charles A. Doswell III (February 2001). "Normalized Damage from Major Tornadoes in the United States: 1890–1999". Weather and Forecasting (American Meteorological Society) 16 (1): 168–176. Bibcode:2001WtFor..16..168B. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(2001)016<0168:NDFMTI>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Wurman, Joshua (2007). "Doppler On Wheels". Center for Severe Weather Research.

- ↑ Snyder, Jeff; Bluestein, H. B. (2014). "Some Considerations for the Use of High-Resolution Mobile Radar Data in Tornado Intensity Determination". Wea. Forecast. doi:10.1175/WAF-D-14-00026.1.

- ↑ By, Forecast. "Capital Weather Gang". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Wright, Celine (June 4, 2013). "Discovery Channel to air special for fallen 'Storm Chasers'". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Bluestein, Howard B.; J.G. Ladue, H. Stein, D. Speheger, W.P. Unruh (August 1993). "Doppler Radar Wind Spectra of Supercell Tornadoes". Monthly Weather Review (American Meteorological Society) 121 (8): 2200–22. Bibcode:1993MWRv..121.2200B. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1993)121<2200:DRWSOS>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Johns, Robert H.; D. W. Burgess, C. A. Doswell III, M. S. Gilmore, J. A. Hart, and S. F. Piltz (2013). "The 1925 Tri-State Tornado Damage Path and Associated Storm System". E-Journal of Severe Storms Meteorology 8 (2).

- ↑ Grazulis, Thomas P. (2001). The Tornado: Nature's Ultimate Windstorm. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3258-2.

- ↑ Martinelli, Jason T. (August 2007). "A detailed analysis of an extremely long-tracked supercell". Preprints of the 33rd Conference on Radar Meteorology. Cairns, Australia: American Meteorological Society and Australian Bureau of Meteorology Research Centre.

- ↑ "Central Oklahoma Tornadoes and Flash Flooding - May 31, 2013". National Weather Service Norman Oklahoma. 2013. Retrieved 2013-06-04.

- ↑ "Event Details". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ↑ Wurman, Joshua; C. Alexander; P. Robinson; Y. Richardson (January 2007). "Low-Level Winds in Tornadoes and Potential Catastrophic Tornado Impacts in Urban Areas". B. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 88 (1): 31–46. Bibcode:2007BAMS...88...31W. doi:10.1175/BAMS-88-1-31.

- ↑ Lee, Wen-Chau; J. Wurman (2005). "Diagnosed Three-Dimensional Axisymmetric Structure of the Mulhall Tornado on 3 May 1999". J. Atmos. Sci. 62 (7): 2379–93. Bibcode:2005JAtS...62.2373L. doi:10.1175/JAS3489.1.

- ↑ "May 1968 Storm Data". National Climatic Data Center.

- ↑ Lee, Julian J.; T. P. Samaras; C. R. Young (October 2004). "Pressure Measurements at the ground in an F-4 tornado". 22nd Conf Severe Local Storms. Hyannis, Massachusetts: American Meteorological Society.

- ↑ "World: Lowest Sea Level Air Pressure (excluding tornadoes)". World Weather / Climate Extremes Archive. Arizona State University.

- ↑ Cerveny, Randall S.; J. Lawrimore; R. Edwards; C. Landsea (2007). "Extreme Weather Records: Compilation, Adjudication, and Publication". B. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 88 (6): 853–60. doi:10.1175/BAMS-88-6-853.

- ↑ Blair, Scott F.; D.R. Deroche, A.E. Pietrycha (2008). "In Situ Observations of the 21 April 2007 Tulia, Texas Tornado". Electronic Journal of Severe Storms Meteorology 3 (3): 1–27.

- ↑ Lee, W.-C.; J. Wurman (Jul 2005). "The diagnosed structure of the Mulhall tornado". J. Atmos. Sci. 62 (7): 2373–93. Bibcode:2005JAtS...62.2373L. doi:10.1175/JAS3489.1.

- ↑ Samaras, Tim M. (October 2004). "A historical perspective of In-Situ observations within Tornado Cores". Preprints of the 22nd Conference on Severe Local Storms. Hyannis, MA: American Meteorological Society.

- ↑ British & European Tornado Extremes

- ↑ Fuentes, Oscar Velasco (November 2010). "The Earliest Documented Tornado in the Americas: Tlatelolco, August 1521". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 91 (11): 1515–23. Bibcode:2010BAMS...91.1515F. doi:10.1175/2010BAMS2874.1.

- ↑ Grazulis, Thomas P. (2001). The Tornado: Nature's Ultimate Windstorm. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3258-2.

- ↑ Erck, Amy (December 26, 2005). "Answers archive: Tornado history, climatology". USA Today Weather (USA Today). Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ↑ Baker, Tim. "Tornado History". tornadochaser.net. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ↑ "Mo. Teen Survives Tornado, Confronts Media Storm". USA Today. March 22, 2006. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ↑ HE SURVIVED A RIDE IN A TORNADO !

- ↑ "Tornado Climatology". A SEVERE WEATHER PRIMER: Questions and Answers about TORNADOES.

- ↑ Fun Tornado Facts - Interesting and Fun Tornado Facts

- ↑ "Moore, Oklahoma Tornadoes (1890-Present)". National Weather Service Norman Oklahoma. 2013. Retrieved 2013-06-05.