Tomorrow Never Knows

| "Tomorrow Never Knows" | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Song by the Beatles from the album Revolver | |||||||

| Released | 5 August 1966 | ||||||

| Recorded |

6, 7 and 22 April 1966 EMI Studios, London | ||||||

| Genre | Psychedelic rock,[1] raga rock,[2] hard rock,[3] experimental rock[4] | ||||||

| Length | 2:58 | ||||||

| Label | Parlophone | ||||||

| Writer | Lennon–McCartney | ||||||

| Producer | George Martin | ||||||

| Revolver track listing | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

"Tomorrow Never Knows" is the final track of the Beatles' 1966 studio album Revolver but the first to be recorded. Credited as a Lennon–McCartney song, it was written primarily by John Lennon.[1]

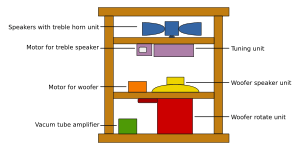

The song has a vocal put through a Leslie speaker cabinet (which was normally used as a loudspeaker for a Hammond organ). Tape loops prepared by the Beatles were mixed in and out of the Indian-inspired modal backing underpinned by Ringo Starr's constant but non-standard drum pattern.

It is considered one of the greatest songs of its time, with Pitchfork Media placing it at number 19 on its list of "The 200 Greatest Songs of the 1960s".[5]

Inspiration

John Lennon wrote the song in January 1966, with lyrics adapted from the book The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead by Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert, and Ralph Metzner, which was in turn adapted from the Tibetan Book of the Dead.[6] Although Peter Brown believed that Lennon's source for the lyrics was the Tibetan Book of the Dead itself, which, he said, Lennon had read whilst consuming LSD,[7] George Harrison later stated that the idea for the lyrics came from Leary, Alpert, and Metzner's book;[8] Paul McCartney confirmed this, stating that when he and Lennon visited the newly opened Indica bookshop, Lennon had been looking for a copy of The Portable Nietzsche and found a copy of The Psychedelic Experience that contained the lines: "Whenever in doubt, turn off your mind, relax, float downstream".[9]

Lennon bought the book, went home, took LSD, and followed the instructions exactly as stated in the book.[10][11] The book held that the "ego death" experienced under the influence of LSD and other psychedelic drugs is essentially similar to the dying process and requires similar guidance.[12][13]

Title

The title never actually appears in the song's lyrics. In an interview Lennon revealed that, like "A Hard Day's Night", it was taken from one of Ringo Starr's malapropisms.[14] The piece was originally titled "Mark I".[9] "The Void" is cited as another working title but according to Mark Lewisohn (and Bob Spitz) this is untrue, although the books The Love You Make: An Insider's Story of the Beatles and The Beatles A to Z both cite "The Void" as the original title.[7]

When the Beatles returned to London after their first visit to America in early 1964 they were interviewed by David Coleman of BBC Television. The interview included the following exchange:

- Interviewer: "Now, Ringo, I hear you were manhandled at the Embassy Ball. Is this right?"

- Ringo: "Not really. Someone just cut a bit of my hair, you see."

- Interviewer: "Let's have a look. You seem to have got plenty left."

- Ringo: (turns head) "Can you see the difference? It's longer, this side."

- Interviewer: "What happened exactly?"

- Ringo: "I don't know. I was just talking, having an interview (exaggerated voice). Just like I am NOW!"

- (John and Paul begin lifting locks of his hair, pretending to cut it)

- Ringo: "I was talking away and I looked 'round, and there was about 400 people just smiling. So, you know — what can you say?"

- John: "What can you say?"

- Ringo: "Tomorrow never knows."

- (John laughs)[15]

Musical structure

McCartney remembered that even though the song's harmony was mainly restricted to the chord of C, Martin accepted it as it was and said it was "rather interesting". The song's harmonic structure is derived from Indian music and is based upon a high volume C drone played by Harrison on a tamboura.[16] The "chord" over the drone is generally C major, but some changes to B flat major result from vocal modulations, as well as orchestral and guitar tape loops.[17][18] The song has been called the first pop song that attempted to dispense with chord changes altogether.[16] Here, the Beatles' harmonic ingenuity is nonetheless displayed in the upper harmonies- "Turn off your mind", for example, is suitably a run of unvarying E melody notes, before "relax" involves an E-G melody note shift and "float downstream" an E-C-G descent.[19] "It is not dying" involves a run of three G melody notes that rise on "dying" to a B♭, creating a ♭VII/I (B♭/C) 'slash' polychord.[19] This is a prominent device in Beatles songs such as "All My Loving", "Help!", "A Hard Day's Night", "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)", "Hey Jude", "Dear Prudence", "Revolution" and "Get Back".[20]

Recording

Lennon first played the song to Brian Epstein, George Martin and the other Beatles at Epstein's house at 24 Chapel Street, Belgravia.[21][22]

The 19-year-old Geoff Emerick was promoted to replace Norman Smith as engineer on the first session for the Revolver album. This started at 8 pm on 6 April 1966, in Studio Three at Abbey Road.[9] Lennon told producer Martin that he wanted to sound like a hundred chanting Tibetan monks, which left Martin the difficult task of trying to find the effect by using the basic equipment they had. The effect was achieved by using a Leslie speaker. When the concept was explained to John, he inquired if the same effect could be achieved by hanging him upside down and spinning him around a microphone while he sang into it.[9][23] Emerick made a connector to break into the electronic circuitry of the cabinet and then re-recorded the vocal as it came out of the revolving speaker.[24][25]

As Lennon hated doing a second take to double his vocals, Ken Townsend, the studio's technical manager, developed an alternative form of double-tracking called artificial double tracking (ADT) system, taking the signal from the sync head of one tape machine and delaying it slightly through a second tape machine.[26] The two tape machines used were not driven by mains electricity, but from a separate generator which put out a particular frequency, the same for both, thereby keeping them locked together.[26] By altering the speed and frequencies, he could create various effects, which the Beatles used throughout the recording of Revolver.[27] Lennon's vocal is double-tracked on the first three verses of the song: the effect of the Leslie cabinet can be heard after the (backwards) guitar solo.[28][29]

The track included the highly compressed drums that the Beatles currently favoured, with reverse cymbals, reverse guitar, processed vocals, looped tape effects, a sitar and a tambura drone.[23] McCartney supplied a bag of ¼-inch audio tape loops he had made at home after listening to Stockhausen's Gesang der Jünglinge. By disabling the erase head of a tape recorder and then spooling a continuous loop of tape through the machine while recording, the tape would constantly overdub itself, creating a saturation effect, a technique also used in musique concrète. The tape could also be induced to go faster and slower. McCartney encouraged the other Beatles to use the same effects and create their own loops.[18] After experimentation on their own, the various Beatles supplied a total of "30 or so" tape loops to Martin, who selected 16 for use on the song.[30] Each loop was about six seconds long.[30]

The tape loops were played on BTR3 tape machines located in various studios of the Abbey Road building[31] and controlled by EMI technicians in Studio Two at Abbey Road on 7 April.[32][23] Each machine was monitored by one technician, who had to hold a pencil within each loop to maintain tension.[30] The four Beatles controlled the faders of the mixing console while Martin varied the stereo panning and Emerick watched the meters.[33][34] Eight of the tapes were used at one time, changed halfway through the song.[33] The tapes were made (like most of the other loops) by superimposition and acceleration.[35][36] According to Martin, the finished mix of the tape loops could not be repeated because of the complex and random way in which they were laid over the music.[37]

Five tape loops are audible in finished version of the song. Isolating the loops reveals that they contained:

- A "laughing" voice, played at double-speed (the "seagull" sound)

- An orchestral chord of B flat major (from a Sibelius symphony) (0:19)

- A fast electric guitar phrase in C major, reversed and played at double-speed (0:22)

- Another guitar phrase with heavy tape echo, with a B flat chord provided either by guitar, organ or possibly a Mellotron Mk II (0:38)

- A sitar-like descending scalar phrase played on an electric guitar, reversed and played at double-speed (0:56)

The Beatles further experimented with tape loops in "Carnival of Light", an as-yet-unreleased piece recorded during the Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band sessions, and in "Revolution 9", released on The Beatles.[38]

The opening chord fades in gradually on the stereo version while the mono version features a more sudden fade-in. The mono and stereo versions also have the tape-loop track faded in at slightly different times and different volumes (in general, the loops are louder on the mono mix). On the stereo version a little feedback comes in after the guitar solo, exactly halfway through the song, but is edited out of the mono mix.

Lennon was later quoted as saying that "I should have tried to get my original idea, the monks singing. I realise now that's what I wanted."[39] Take one of the recording was released on the Anthology 2 album.[39]

Interpretation

Harrison questioned whether Lennon fully understood the meaning of the song's lyrics:

You can hear (and I am sure most Beatles fans have) "Tomorrow Never Knows" a lot and not know really what it is about. Basically it is saying what meditation is all about. The goal of meditation is to go beyond (that is, transcend) waking, sleeping and dreaming. So the song starts out by saying, "Turn off your mind, relax and float downstream, it is not dying."

Then it says, "Lay down all thoughts, surrender to the void—it is shining. That you may see the meaning of within—it is being." From birth to death all we ever do is think: we have one thought, we have another thought, another thought, another thought. Even when you are asleep you are having dreams, so there is never a time from birth to death when the mind isn't always active with thoughts. But you can turn off your mind, and go to the part which Maharishi described as: "Where was your last thought before you thought it?"

The whole point is that we are the song. The self is coming from a state of pure awareness, from the state of being. All the rest that comes about in the outward manifestation of the physical world (including all the fluctuations which end up as thoughts and actions) is just clutter. The true nature of each soul is pure consciousness. So the song is really about transcending and about the quality of the transcendent.

I am not too sure if John actually fully understood what he was saying. He knew he was onto something when he saw those words and turned them into a song. But to have experienced what the lyrics in that song are actually about? I don't know if he fully understood it.[40]

Personnel

- John Lennon – double-tracked vocal, Hammond organ and tape loops

- Paul McCartney – bass, backwards guitar solo and tape loops

- George Harrison – sitar, tamboura, and tape loops

- Ringo Starr – drums, tambourine and tape loops

- George Martin – piano, producer

- Geoff Emerick – engineer

- Personnel per Ian MacDonald[41]

The Love album remix

In 2006, Martin and his son, Giles Martin, remixed 80 minutes of Beatles music for the Las Vegas stage performance Love, a joint venture between Cirque du Soleil and The Beatles' Apple Corps Ltd.[42] On the Love album, the rhythm to "Tomorrow Never Knows" was mixed with the vocals and melody from "Within You Without You", creating a different version of the two songs. The soundtrack album from the show was released in 2006.[43][44] The Love remix is one of the main songs in The Beatles: Rock Band music video game.[45]

In popular culture

In music

DJ Spooky said of the track in 2011:

"Tomorrow Never Knows" is one of those songs that's in the DNA of so much going on these days that it's hard to know where to start. Its tape collage alone makes it one of the first tracks to use sampling really successfully. I also think that Brian Eno's idea of the studio-as-instrument comes from this kind of recording.[46]

The song has been covered by numerous musicians:

- A 1968 cover by Jimi Hendrix is included on the 1980 posthumous bootleg Woke Up This Morning and Found Myself Dead.

- The Pink Fairies played extended versions of the song at many 1970s pop festivals.

- On 3 September 1976 a live, full-scale rearrangement was recorded by the band 801, with personnel including Phil Manzanera and Brian Eno.

- Phil Collins covered the song, as a tribute to the recent death of John Lennon, on his 1981 album Face Value, ending with an a cappella snippet of "Over the Rainbow".

- Monsoon covered it on a 1982 single, included on their album Third Eye.

- The Mission recorded their version in 1986 for the "Severina" single. It was later included on the singles compilation The First Chapter.

- The Chameleons also recorded a version, included as a bonus track on their 1986 album Strange Times.

- Danielle Dax covered the song on her 1990 album Blast The Human Flower.

- Jad Fair and Daniel Johnston covered the song on their 1989 album It's Spooky, adding a twist to the lyrics after the final verse when Johnston enters shouting:

- "No! No! Ladies and gentlemen, do not surrender to the void! The darkness surrounds you—don't relax! You'll never get out of that pit! No! No! It isn't love—the demons will enter! No! No! No!"

- Listed in setlists as "TNK", The Grateful Dead performed the song 12 times in the 1990s, always segueing out of The Who's "Baba O'Riley".[47] Subsequently, former Grateful Dead members Phil Lesh, Bob Weir, and Vince Welnick have played the song in their post-Dead projects.[48]

- Michael Hedges covered the song on his 1996 album Oracle.

- Funk metal band Living Colour covered the song on their 2003 album Collideøscope.

- Psychedelic rock band Violeta de Outono covered the song on their 1987 eponymous debut.

- Reggae group The Wailing Souls included a version on their 1998 all-cover album Psychedelic Souls.

- Portland band Helio Sequence covered the song on their 2000 album Com Plex.

- David Lee Roth covered the song on his 2003 album Diamond Dave, listed in the track list as "That Beatles Tune".

- Parody band Beatallica recorded a mashup of "Tomorrow Never Knows" and Metallica's "The Day That Never Comes" entitled "Tomorrow Never Comes", on their 2009 album Masterful Mystery Tour.

- Herbie Hancock recorded a cover of "Tomorrow Never Knows" for his 2010 album The Imagine Project featuring Dave Matthews on vocals. Also, Matthews often performs an excerpt of "Tomorrow Never Knows" during live versions of his band's song "Minarets".

- Alison Mosshart recorded a "wildly re-imagined" 7 minute 35 second version of the song for the 2011 Sucker Punch: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack

The song is referenced in the lyrics to the 1995 Oasis song "Morning Glory": "Tomorrow never knows what it doesn't know too soon".

The Chemical Brothers refer to "Tomorrow Never Knows" as their "manifesto"; their 1996 track "Setting Sun" is a direct tribute to it.

Our Lady Peace recorded a cover of "Tomorrow Never Knows" for the 1996 film The Craft, and a cover by Carla Azar and Alison Mosshart is featured in the 2011 motion picture Sucker Punch. Gov't Mule covers the song frequently live, often played with "She Said, She Said".

In television

The song was featured during the final scene of the 2012 Mad Men episode "Lady Lazarus." Don Draper's wife Megan gives him a copy of Revolver, calling his attention to a specific track and suggesting, "Start with this one".[49] Draper, an advertising executive, is struggling to understand youth culture, but after contemplating the song for a few puzzled moments, he shuts it off.[50] The song also played over the closing credits.[51] The rights to the song cost the producers about $250,000,[50] "about five times as much as the typical cost of licensing a song for TV."[49]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Gilliland 1969, show 39, tracks 4-5.

- ↑ Peter Lavezzoli, The Dawn of Indian music in the West: Bhairavi(Continuum International Publishing Group), ISBN 0-8264-1815-5, p.175

- ↑ The 100 Most Influential Musicians of All Time, by Gini Gorlinski, "the hallucinatory hard rock song 'Tomorrow Never Knows'"

- ↑ Unterberger 2009.

- ↑ Staff Lists: The 200 Greatest Songs of the 1960s | Features | Pitchfork

- ↑ MacDonald 2005, p. 188.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Brown & Gaines 1980.

- ↑ Harrison 1995.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Spitz 2005, p. 600.

- ↑ Lennon.

- ↑ Spitz 2005, pp. 600–601.

- ↑ The New York Times 1996.

- ↑ Summum 2009.

- ↑ The Beatles Interview Database 2009.

- ↑ The Beatles Interview Database 1964.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Peter Lavezzoli. The Dawn of Indian Music in the West. Bhairavi. The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc. New York 2006. ISBN 0-8264-1815-5 ISBN 978-0-8264-1815-9, 2006. p175

- ↑ Miles 1997, pp. 291–292.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Spitz 2005, p. 601.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Pedler, Dominic (2003). The Songwriting Secrets of the Beatles. London: Omnibus Press. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-7119-8167-6.

- ↑ Pedler, Dominic (2003). The Songwriting Secrets of the Beatles. London: Omnibus Press. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-7119-8167-6.

- ↑ Miles 1997, p. 290.

- ↑ Google Maps 2007.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Miles 1997, p. 291.

- ↑ Martin 1995a.

- ↑ Spitz 2005, p. 602.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Martin 1994, p. 82.

- ↑ Spitz 2005, p. 603.

- ↑ "Tomorrow Never Knows" (Verses 4/7—1:27 until 2:47)

- ↑ MacDonald 2005, p. 191.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Martin 1994, p. 80.

- ↑ Martin 1994, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ McCartney 1995.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Martin 1994, p. 81.

- ↑ MacDonald 1995.

- ↑ Miles 1997, p. 292.

- ↑ MacDonald 1995, p. 190.

- ↑ Martin 1995b.

- ↑ Marinucci 2007.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Harry 2000, p. 1078.

- ↑ The Beatles Anthology. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. 2000. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-304-35605-8.

- ↑ MacDonald 2005, p. 185.

- ↑ Watson 2006.

- ↑ Paine 2006.

- ↑ CTV News 2006.

- ↑ Frushtick 2009.

- ↑ Thill, Scott (9 June 2011). "Paul McCartney Brings 'Tomorrow Never Knows' Back to the Future". wired.com. wired.com. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ↑ "DeadBase". Deadbase.com. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ↑ "For all your setlist needs!". Setlist.com. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Jurgensen, John (7 May 2012). "How Much ‘Mad Men’ Paid for The Beatles". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2014-09-27.

Don Draper unsheathed a Revolver LP and cued up the song "Tomorrow Never Knows." The general reaction on Twitter was, 'Whoa.' That sentiment was immediately followed by something like, "How much did that cost them?" Answer: about $250,000, according to people familiar with the deal. That’s about five times as much as the typical cost of licensing a song for TV. In an interview, series creator Matthew Weiner disputed that figure, but declined to discuss financial details of the deal. The surviving Beatles, along with Yoko Ono and Olivia Harrison, signed off on the "Mad Men" usage.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Itzkoff, Dave and Ben Sisario (7 May 2012). "How 'Mad Men' Landed the Beatles: All You Need Is Love (and $250,000)". New York Times. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ↑ Leeds, Sarene (7 May 2012). "'Mad Men' Recap: Secrets and Lies". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

References

- "Revolver". The Beatles Interview Database. 2009. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- "Return to London from the USA". The Beatles Interview Database. 22 February 1964. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

- Brown, Peter; Gaines, Steven (1980). The Love You Make: An Insider's Story of The Beatles. Methuen Publishing. ISBN 978-0-451-20735-7.

- "Beatles, Radiohead albums voted best ever". CNN. 2007. Archived from the original on 13 September 2007. Retrieved 27 October 2007.

- "Beatles smash hits now a mashup". CTV News. 21 November 2006. Retrieved 27 October 2007.

- Friede, Goldie (2005). The Beatles A To Z (1st ed.). London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-416-00781-7.

- Frushtick, Russ (21 July 2009). "'The Beatles: Rock Band' Expands Its Song List". mtv.com.

- Gilliland, John (1969). "The Rubberization of Soul: The great pop music renaissance." (AUDIO). Pop Chronicles. Digital.library.unt.edu.

- "24 Chapel Street, Belgravia". Google Maps. 2007. Retrieved 27 October 2007.

- Harrison, George (1995). The Beatles Anthology (DVD). Event occurs at Special Features, Back at Abbey Road May 1995, 0:10:59.

- Harry, Bill (2000). Beatles Encyclopedia. Virgin Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-7535-0481-2.

- "Children of Men soundtrack". IMDB. 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- Lennon, John. The Beatles Anthology (DVD). Event occurs at Episode 7, 0:10:05.

- MacDonald, Ian (2005). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties (Second Revised ed.). London: Pimlico (Rand). ISBN 1-84413-828-3.

- Marinucci, Steve (2007). "Carnival of Light". abbeyrd.best. Retrieved 27 October 2007.

- Martin, George (1994). Summer of Love: The Making of Sgt Pepper. MacMillan London Ltd. ISBN 0-333-60398-2.

- Martin, George (1995a). The Beatles Anthology (DVD). Event occurs at Special Features, Back at Abbey Road May 1995, 0:09:06.

- Martin, George (1995b). The Beatles Anthology (DVD). Event occurs at Special Features, Back at Abbey Road May 1995, 0:13:32.

- McCartney, Paul (1995). The Beatles Anthology (DVD). Event occurs at Special Features, Back at Abbey Road May 1995, 0:12:17.

- Miles, Barry (1997). Many Years From Now. Vintage-Random House. ISBN 0-7493-8658-4.

- Mansnerus, Laura (1 June 1996). "Pied Piper Of Psychedelic 1960s, Dies at 75". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 October 2007.

- Paine, Andre (17 November 2006). "Legendary producer returns to Abbey Road". BBC News. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

- Spitz, Bob (2005). The Beatles: The Biography. New York: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 1-84513-160-6.

- "The first English language translation of the famous Tibetan death text". Summum. 2009. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- Unterberger, Richie (2009). "Review of "Tomorrow Never Knows"". Allmusic. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- Watson, Greig (17 November 2006). "Love unveils new angle on Beatles". BBC News.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Revolver (Beatles album) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||