Tom Wills

| Tom Wills | |

|---|---|

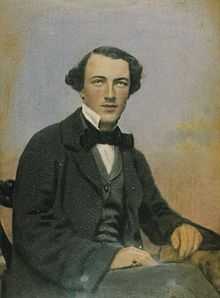

Wills, c. 1857 | |

| Born |

Thomas Wentworth Wills 19 August 1835 Molonglo Plain, New South Wales, Australia |

| Died |

2 May 1880 (aged 44) Heidelberg, Victoria, Australia |

| Known for | Revolutionising cricket in Australia and co-inventing Australian rules football |

Thomas Wentworth "Tom" Wills (19 August 1835 – 2 May 1880) was a 19th-century sportsman who is credited with being Australia's first cricketer of significance and a pioneer of the sport of Australian rules football.

Born in the British colony of New South Wales to a wealthy family descended from convicts, Wills grew up on properties owned by his father, the pastoralist and nationalist Horatio Wills, in what is now the Australian state of Victoria. He befriended local Aborigines, learning many aspects of their culture. At the age of 14, Wills was sent to England to attend Rugby School, where he became captain of Rugby's cricket team, and played an early version of rugby football. After Rugby, Wills represented the Cambridge University Cricket Club in the annual match against Oxford, and played in first-class matches for Kent and the Marylebone Cricket Club. An athletic all-rounder with devastating bowling analyses, he was regarded as one of the finest young cricketers in England.

Returning to Victoria in 1856, Wills achieved Australia-wide stardom as a cricketer, captaining the Victorian team to repeated victories in intercolonial matches. He played for many clubs, most prominently the Melbourne Cricket Club, for which he served as honorary secretary. In 1858 he called for the formation of a "foot-ball club" with a "code of laws" to keep cricketers fit during the off-season. After founding the Melbourne Football Club the following year, Wills and three other members codified the first laws of Australian rules football. He and his cousin H. C. A. Harrison spearheaded the new sport as players and administrators.

In 1861, at the height of his fame, Wills joined his father on a trek to Queensland to establish a family property. Two weeks after their arrival, Wills' father and 18 others were murdered in the largest massacre of European settlers by Aborigines in Australian history. Wills survived and returned to Victoria in 1864. He continued to play football and cricket, and, in 1866–67, coached and captained an Aboriginal cricket team—the first Australian XI to tour England. In a career marked by controversy, Wills straddled the divide between amateur and professional cricketers, and was frequently accused of bending rules to the point of cheating. He was no-balled twice for throwing in 1872 and mounted a failed comeback four years later on the brink of the birth of Test cricket, by which time his sporting glory belonged to a colonial past that seemed "quaint and old fashioned".[1] Psychological trauma from the massacre was worsened by his alcoholism. Now destitute, Wills was admitted to the Melbourne Hospital in 1880, suffering from delirium tremens, but shortly afterwards escaped and returned to his home in Heidelberg, where he committed suicide by stabbing a pair of scissors through his heart.

Wills fell into obscurity after his death, but since the 1990s, he has undergone a resurgence in Australian culture. He was an inaugural inductee into the Australian Football Hall of Fame, and is commemorated with a statue outside the Melbourne Cricket Ground. In modern times he is characterised as an archetype of the tragic sports hero, and as a symbol of reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. The claim of an Aboriginal influence on Wills' conception of Australian football has been the subject of heated debate. According to biographer Greg de Moore, Wills "stands alone in all his absurdity, his cracked egalitarian heroism and his fatal self-destructiveness—the finest cricketer and footballer of the age."[2]

Family and early years

.tif.jpg)

Tom Wills was born on 19 August 1835 on the Molonglo Plain[a] near modern-day Canberra, in what was the British penal colony of New South Wales, as the elder child[b] of Horatio and Elizabeth (née McGuire) Wills.[3] Tom was a third-generation Australian descended from convicts: his mother was born to convicts transported from Ireland, and his paternal grandfather was Surrey labourer Edward Wills, whose death sentence for highway robbery was commuted to transportation, arriving in Botany Bay aboard the "hell ship" Hillsborough in 1799.[4] Edward received a conditional pardon in 1803 and amassed immense wealth through mercantile activity in Sydney with his free wife Sarah (née Harding).[5] Horatio was born the youngest of six children in 1811, five months after his father's death, and Sarah remarried to convict George Howe, owner of Australia's first newspaper, the Sydney Gazette.[6] During his tenure as the newspaper's editor, Horatio met Elizabeth, an orphan from Parramatta. They married in December 1833.[7] Seventeen months after his birth, Tom was baptised Thomas Wentworth Wills in the parish of St Andrew's, Sydney, after statesman William Charles Wentworth.[8] Influenced by Wentworth's pro-Currency writings and the emancipist cause, Horatio set forth a strident nationalist agenda in his 1832–33 journal The Currency Lad, the first publication to call for an Australian republic.[9]

Seeking to translate his rhetoric into action, Horatio took up pastoral pursuits in the mid-1830s and moved with his family to the sheep run "Burra Burra" on the Molonglo River.[10] Although athletic from an early age, Tom was prone to illness, and at one stage in 1839 his parents "almost despaired of his recovery".[11] In November 1840, in light of Thomas Mitchell's discovery of "Australia Felix", they overlanded south to the Grampians in the colony's Port Phillip District (now the state of Victoria), and, after establishing a run on Mount William, settled a few miles north in the foothills of Mount Ararat, named so by Horatio because "like the Ark, we rested there".[12] Horatio went through a period of intense religiosity while in the Grampians; at times his diary descends into incantation, "perhaps even madness".[13] He implored himself and Tom to base their lives upon the New Testament.[14]

Horatio built a homestead on a large property named "Lexington" (near present-day Moyston) in an area that served as a meeting place for Djab wurrung Aboriginal clans.[15] Tom, as an only child, "was thrown much into the companionship of aborigines", and "became a thorough linguist in the native dialects".[16] In an account of corroborees from childhood, H. C. A. Harrison[c] remembered his cousin Tom's ability to learn Aboriginal songs, mimic their voice and gestures, and "speak their language as fluently as they did themselves, much to their delight."[17] It is speculated that Tom may have also played Aboriginal sports.[18] Horatio wrote fondly of his son's kinship with Aborigines, and allowed local clans to live and hunt on Lexington.[19] However, like many frontiersmen in the area, he was implicated in deadly conflict with the Djab wurrung.[d]

Tom's first sibling, Emily, was born on Christmas Day 1842.[20] In 1846 Wills began attendance at William Brickwood's School in Melbourne. There he was looked after by Horatio's brother Thomas (Tom's namesake[8]), a Victorian separatist and son-in-law of the Wills family's partner in the shipping trade, convict Mary Reibey.[21] Tom played in his first cricket matches at school, and he came in contact with the Melbourne Cricket Club through Brickwood, the club's vice-president.[22] Wills returned to Lexington in 1849 where the family had grown to include siblings Cedric, Horace and Egbert.[23] Mainly self-educated, Horatio had ambitious plans for the education of his children, especially Tom:[14]

I now deeply vainly deplore my want of a mathematical and classical education. Vain regret! ... But my son! May he prove worthy of my experience! May I be spared for him—that he may be useful to his country—I never knew a father's care.

England

Rugby School

Wills' father sent him to England in February 1850, aged fourteen, to attend Rugby School, the most prestigious school in the country.[24] Horatio wanted Tom to study law and return to Australia as a "professional man of eminence".[25] He arrived in London after a five-month voyage. There, during school holidays, he stayed with his paternal aunt Sarah, who moved from Sydney after the death of her first husband, convict William Redfern.[24]

The reforms enacted by Thomas Arnold, famed headmaster, made Rugby the crucible of muscular Christianity, a "cult of athleticism" into which Wills was inculcated.[26] Wills took up cricket within a week of entering Evans House.[27] At first he bowled underhand, but it was considered outdated, so he tried roundarm bowling. He clean bowled a batsman with his first ball using this style and declared: "I felt I was a bowler."[28] Wills soon topped all of his house's cricket statistics.[29] At bat he was a "punisher" with a sound defence.[30] However, in an age when style was key, he was deemed to have no style at all.[31] In April 1852, when he was sixteen, Wills joined the Rugby School XI, and on his debut at Lord's a few months later, against the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), he took a match-high 12 wickets.[32] That year he formed one half of a bowling attack that established Rugby as the greatest public school in English cricket.[32] In a prelude to his colonial career, critics in the national media accused him of throwing.[33] Rugby coach John Lillywhite rallied in defence of his protégé.[34] Wills survived the scandal.[35] He won fame for his performances and played with the leading cricketers of the age, as well as royalty.[36] William Clarke, his hero, invited him to join the touring All-England Eleven, but he remained at Rugby.[37] Then in 1855 he took over as Rugby XI captain, the most revered position within the school.[38]

"I know that if I [study] too hard I will become quite ill. We hardly get any play during school time."

Rugby, like other English public schools, had evolved its own variant of football.[40] The game in Wills' era—a rough and highly defensive struggle involving hundreds of boys—was confined to a competition amongst the houses.[41] Spanning the years he played, Wills is pivotal to any of the brief match reports in Bell's Life in London.[42] His creative play and "eel-like agility" baffled the opposition, and his penchant for theatrics endeared him to the crowds.[43] One journalist noted his use of "slimy tricks", a possible reference to his gamesmanship.[43] As a "dodger" in the forward line, he was a long and accurate shot at goal and served as his house's kicker.[44] Wills also shone in the school's annual athletics carnival and his long-distance running ability in Hare and Hounds was unparalleled.[45]

Wills cut a dashing figure with "impossibly wavy" hair and blue, almond-shaped eyes that "[burnt] with a pale light".[46] By age 16 at 5'8" he was already taller than his father.[47] In Lillywhite's Guide a few years later his height was recorded as 5'10" and it was written that "few athletes can boast of a more muscular and well-developed frame".[48]

Consumed by sport, Wills failed to advance academically.[49] It was said that he "could not bring himself to study for professional work" after "having led a sort of nomadic life when a youth in Australia".[50] Wracked by homesickness, he decorated his study with objects to remind him of Lexington, including Aboriginal weapons.[51] Horatio wrote to remind him of his childhood friends: "[the Djab wurrung] told me to send you up to them as soon as you came back."[52]

Libertine cricketer

| Cricket information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batting style | Right-handed | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bowling style | Right-arm slow | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Role | All-rounder | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domestic team information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years | Team | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1854 | Gentlemen of Kent | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1855 | Gentlemen of Kent and Surrey | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1855–56 | Marylebone Cricket Club | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1855–56 | Kent | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1856 | Kent and Sussex | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1856 | Gentlemen of Kent and Sussex | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1856 | Cambridge University | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1856–76 | Victoria | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1864 | G. Anderson's XI | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Umpiring information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| FC umpired | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Career statistics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: CricketArchive, 24 April 2012 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wills had built a reputation as "one of the most promising cricketers in the kingdom".[53] Held aloft as Rugby's exemplar sportsman, his status as a cricketer came to define him.[54] In June 1855, nearing his 20th birthday, Wills finished his schooling. In a farewell note from his fellow students he was simply called "the school bowler".[55]

After leaving Rugby, and with a steady supply of money, Wills wandered throughout Great Britain in pursuit of cricketing pleasure. He made first-class appearances for the MCC, Kent, and various Gentlemen sides, and also fell in with the I Zingari—the "gypsy lords of English cricket"—an amateur club known for its exotic costumes and hedonistic lifestyle.[56] Against Horatio's wishes, Tom did not continue his studies at Cambridge, but did play cricket for the university's team (as well as Magdalene College), most notably when rules were passed over to allow him to compete against Oxford in the 1856 University Match, Cambridge being "one man short".[57] In June, Wills played cricket at Rugby School for the last time, representing the MCC alongside Lord Guernsey, the Earl of Winterton, and Charles du Cane, governor-to-be of Tasmania.[58] Wills spent a month playing for various clubs in Ireland, after which he returned to England in early September to prepare for his journey home to Australia.[59]

The last eighteen months had exposed Wills to "the richest sporting experience on earth".[60] His six years in England charted a way of life that would continue to define him until his death.[60]

Colonial hero

Wills returned to Australia aboard the Oneida steamship, arriving in Melbourne on 23 December 1856. The minor port city of his youth had risen to world renown as the booming financial centre of the Victorian gold rush.[61] Horatio, now a member of the Legislative Assembly in the Victorian Parliament, was living on "Belle Vue", a farm at Point Henry near Geelong, the Wills' family home since 1853.[62] In his first summer back in Melbourne, Wills stayed with his extended family, the Harrisons, at their home on Victoria Parade, and entered a Collins Street law firm to appease his father, but he seems never to have practiced; the few comments he made about law suggest it meant little to him.[63] "Tom was no dunce", writes Greg de Moore. "He was simply negotiating a path to greatness."[64]

The Australian colonies were described as "cricket mad" in the 1850s, and Victorians, in particular, were said to "live, move, and have their being in an atmosphere of cricket".[65] Intercolonial cricket contests, first held in 1851, provided an outlet for the at times intense rivalry between Victoria and New South Wales. With his reputation preceding him, Wills became the bearer of Victoria's hopes of winning its first match against the elder colony.[66] Victorian captain William Hammersley recalled the moment when Wills first graced the Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG) for a trial match, staged one week after his return:[48]

... the observed of all observers, with his Zingari stripe and somewhat flashy get up, fresh from Rugby and college, with the polish of the old country upon him. He was then a model of muscular Christianity.

Wills' batting style drew mirth from the crowd, but he won the trial for his team with 57 not out.[67] In January, he travelled as part of the Victorian XI to Sydney to play against New South Wales on the Domain. Wills was the leading wicket-taker with 10 victims. Bowling fast round-arm, the Victorians regarded themselves as superior to their opponents, who used an "antiquated" underhand action. The latter style proved effective, giving New South Wales a 65-run win.[68] Wills spent the rest of the season playing for numerous clubs, most notably the Melbourne Cricket Club (MCC).[69]

Parliament and business came to a standstill for the January 1858 intercolonial match, held at the MCG. Wills captained Victoria against New South Wales.[70] He took 8 wickets, the most of his side, and on the second day, batting in the middle order, a ball hit an imperfection in the pitch and knocked him unconscious. He rose after several minutes, batted for another two hours, and ended the day with a match-winning 49 not out.[71] The crowd rushed the field and carried Wills in triumph upon their shoulders, and victory celebrations lasted for a week throughout the colony.[72] Wills, now a household name and the darling of Melbourne's elite, was proclaimed "the greatest cricketer in the land".[73]

Although Wills enjoyed his lofty amateur status, he liked to socialise with and support working class professional cricketers—an egalitarian attitude that sometimes led to conflict with sporting officialdom but endeared him to the common man.[74] Wills' allegiance to professionals was highlighted by an incident in Tasmania in February 1858 when the Launceston Cricket Club shunned professional members of his touring Victorian side. "We have been in a strange land, and forsaken" a furious Wills wrote to the press. One week later, during a Hobart game, Wills earned the locals' ire as he "[jumped] about exultantly" after maiming a Tasmanian batsman with a spell of hostile fast bowling.[75]

Wills succeeded Hammersley as secretary of the MCC during the 1857–58 season.[76] It was a role in which he proved to be utterly chaotic and disorganised. MCC delegates took issue with Wills' "continued non-attendance" at meetings, and when the club fell into debt, his poor administrative skills were blamed.[77] Wills acted on year-long threats in mid-1858 and deserted the MCC to join Richmond, raising the standard of its play to make it the premier Victorian club. He left the MCC's amenities in a pile of trash; to this day, the only MCC minute book that cannot be found is from his time as secretary.[78] There was a lasting tension between Wills and the club's inner circle. According to Martin Flanagan, "It was a relationship which couldn't last as Wills only knew one way—his own."[79]

"A game of our own"

"... when T. W. Wills arrived from England, fresh from Rugby school, full of enthusiasm for all kinds of sports, he suggested that we should make a start with it. He very sensibly advised us not to take up Rugby, although that had been his own game because he considered it as then played unsuitable for grown men, engaged in making a livelihood, but to work out a game of our own."

Wills was a compulsive writer to the press on sporting matters and in the late 1850s his letters appeared on an almost daily basis.[81] An agitator like his father, he used language "in the manner of a speaker declaiming forcefully from a platform".[82] On 10 July 1858, the Melbourne-based Bell's Life in Victoria and Sporting Chronicle published a letter by Wills that is regarded as a catalyst for a new style of football, known today as Australian rules football.[83] It begins:[84]

Now that cricket has been put aside for some few months to come, and cricketers have assumed somewhat of the chrysalis nature (for a time only 'tis true), but at length will again burst forth in all their varied hues, rather than allow this state of torpor to creep over them, and stifle their new supple limbs, why can they not, I say, form a foot-ball club, and form a committee of three or more to draw up a code of laws?

In endeavouring to bring his English sporting experience to Melbourne, Wills made the first public declaration of its kind in Australia: that football should be a regular and organised activity.[85] He went on to foster football in Melbourne's schools. The local headmasters, his collaborators, were inspired in large part by Thomas Hughes' novel Tom Brown's School Days (1857), an account of life at Rugby School under the headship of Thomas Arnold.[86] Tom Brown, like Wills, had captained the Rugby XI and excelled at the school's football game. It led to the impression that Wills was the fictitious hero's "real-life embodiment".[87]

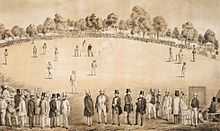

While the letter drew no immediate response, it was alluded to three weeks later in an advertisement for a "scratch match" held adjacent to the MCG at the Richmond Paddock, organised with the help of Wills' friend, professional cricketer and publican Jerry Bryant. It was suggested that "a short code of rules" would be decided upon afterwards, however this does not seem to have occurred.[88] Another landmark game, played without fixed rules over three Saturdays and co-umpired by Wills and John Macadam, began on the same site on 7 August between forty students of Scotch College and a like number from Melbourne Grammar.[89] The two schools have since competed annually.[90]

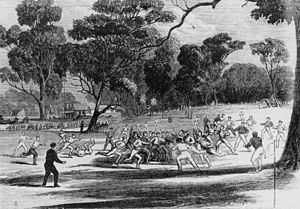

Wills emerged as the leading light of the men who organised matches in Melbourne's parklands during the winter of 1858.[91] These early games, experimental in nature, were more rugby-like than anything else—low-scoring, low-to-the-ground "gladiatorial" tussles.[92] The last recorded match of the year is the subject of the first known Australian football poem, published in Punch. Wills, the only player mentioned by name, is reified as "the Melbourne chief", leading a phalanx of his men to kick the winning goal against a South Yarra team.[93]

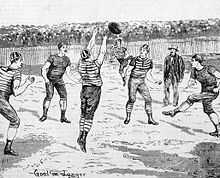

The Melbourne Football Club officially came into being on 14 May 1859.[94] Three days later, Wills and three other members—Hammersley, J. B. Thompson and Thomas H. Smith—met at Bryant's Parade Hotel in East Melbourne to frame the club's rules. The resulting ten rules form the basis of Australian rules football, the oldest football code outside the English public-school system.[95] Wills heads the list of signatories.[96] The men went over the rules of four English schools; Hammersley recalled Wills' preference for the Rugby game.[97] These were found to be confusing and too violent. Subsequently, features such as "hacking" (shin-kicking) were rejected and a simple code suited to grown men and Australian conditions was devised.[98] Wills, too, saw the need for compromise.[99] He wrote to his brother Horace: "Rugby was not a game for us, we wanted a winter pastime but men could be harmed if thrown on the ground so we thought differently."[96] Thompson, a journalist, promoted the Melbourne rules in The Argus, and by 1860, new clubs had formed across Victoria.

Victoria's reign and football evolves

The January 1859 intercolonial cricket match took place on the Domain in Sydney. Wills was elected captain, and despite dislocating his right middle finger on the first day while attempting a catch, top scored in the first innings with 15 not out and took 5/24 and 6/25, carrying Victoria to an upset win.[100] He resigned from the intercolonial match committee in protest after being assailed by Thompson for not turning up to practice ahead of the next match against New South Wales.[101] During a follow-up practice game, players struggled in the day's heat, and ignoring calls to retire, Wills suffered from a near-fatal sunstroke. Hammersley wrote that Wills felt obliged to perform for the large crowd that had gathered to watch him.[102] Over 25,000 people attended the Victoria and New South Wales match, held at the MCG in February 1860. Wills captained Victoria and bowled unchanged in both innings, taking 6/23 and 3/16, and ended with a top score of 20 not out. Victoria won by 69 runs.[103] These successive victories won Wills the sobriquet "Great Gun of the Colony".[104] The 1859–60 Victorian Cricketers' Guide described him as the ultimate all-rounder.[105] The Sydney press, parading Wills as a native New South Welshman, agreed:[106]

Tall, muscular, and slender, Mr. Wills seems moulded by nature to excel in every branch of the noble game, and with the ball at the wicket, and on the field we find him the admiration of the ground, while in the combination of his successes, his noble eleven recognise with pride the still more arduous duties of an unwearied and most discreet captain.

The laws of football underwent further revisions in the early 1860s, mostly to set limits on running and ball handling.[107] In April 1860, Wills was the inaugural captain and secretary of the Richmond Football Club (no connection with the present AFL club), and advised the team on their colours: white with a red sash.[108] The following month, a debate over the ball's shape came to a head when Wills, captaining Richmond against Melbourne, maintained his right to play with an oval ball, which flew further than the prevailing round ball (a fact that Wills, the colony's longest kick, would have used this to his advantage[109]). The oval ball became customary in the sport by the 1870s.[110]

"I think the ground should be free to all, so that the captain of each side could dispose of his forces in any position he likes; and when this is done, and the ball is carried on from one end of the ground to the other, by a succession of good, well-directed kicks, to the hands of those that the ball was intended for, ... it has a very pretty effect, and is the result of some skill."

Early matches were organised with little formality. After an 1860 match between University and Richmond was abandoned, University secretary G. C. Purcell accused the Richmond team of not showing. Wills retorted that University's men "must have been dodging behind the gum trees, for they were not visible."[112]

By 1860, Wills' cousin H. C. A. Harrison had become a leading footballer in Melbourne. He looked up to Wills, once calling him "the beau-ideal of an athlete"—high praise considering that Harrison was the fastest runner of the colonies.[113] The pair's presence in Geelong fuelled a local craze for football and ensured that the Geelong Football Club dominated the sport in the early 1860s.[114]

Of the early footballers, Wills was appraised as the greatest, most astute captain, and it is claimed that, unbound by offside rules, he opened up the game to innovative tactics and skills and a more free-flowing style of play.[115] In July 1860 he foreshadowed modern positional football when he told his Richmond players to abandon the congested playing style typical of the era and instead form a line from defence to attack, and, by a series of short kicks to one another towards goal, succeeded in scoring.[116] In another match, captaining Melbourne to victory, he exploited the lower number of players on the field by instructing his men to dart with the ball in open spaces.[116] Historian Geoffrey Blainey writes: "How many of the tricks and stratagems of the early years came from this clever tactician we will never know."[117]

Queensland

With plans underway for the first tour of Australia by an English cricket team, Wills announced his retirement from sport. At the beckoning of his father, Wills was preparing to leave Victoria to establish a new family property, Cullin-La-Ringo, on the Nogoa River in outback Queensland.[118] For six months he worked in country Victoria and learnt the station crafts of a squatter, such as shearing and blacksmithing.[119]

In January 1861, Tom, Horatio and a party of employees and their families travelled by steamer to Brisbane, disembarked in Moreton Bay, and then, with livestock and supplies, set out on an eight-month trek through Queensland's rugged interior.[119] Food was scarce and Tom hunted native game to fend off starvation.[120] They suffered many other hardships and even death when, in Toowoomba, one of Horatio's men drowned.[120] On the Darling Downs over 10,000 sheep were collected.[121] The size of the Wills party attracted the attention of local Aborigines, and the two groups engaged in games of mimicry.[122] Wary of entering the region's frontier war, Horatio maintained a conciliatory attitude to the Aborigines.[123] The party reached Cullin-la-Ringo, situated on Kairi Aboriginal land, in early October, and proceeded to set up camp.[124]

Cullin-la-Ringo massacre

On the afternoon of 17 October, two weeks after their arrival, Horatio and eighteen of his party were murdered in the deadliest massacre of settlers by Aborigines in Australian history.[125] Tom was away from the property at the time, having been sent with two stockmen to collect supplies left en route to Cullin-la-Ringo. He returned several days later to a scene of devastation.[122] Despairing and in shock, Wills immediately wrote to H. C. A. Harrison in Melbourne: "... all our party except I have been slaughtered by the black's on the 17th. I am in a great fix no men."[126] In the swift retribution that followed, police, native police and vigilante groups from neighbouring stations tracked down and killed at least 70 local Aborigines; the total may have been 300.[127] Wills took refuge near Cullin-la-Ringo, and despite his desire for vengeance, there is no evidence that he joined the reprisal raids.[128]

Conflicting reports reached the outside world and for a time it was feared that Tom had died.[129] Horatio was accused in the press of ignoring warnings and allowing Aborigines to encroach on his property.[130] Others felt that the retribution was excessive.[131] Tom, a lone voice in defence of his father, bitterly rebuked both groups.[130] Privately, in his first letter to Harrison, he admitted, "if we had used common precaution all would have been well".[132] It was later revealed that, prior to leaving the camp, Tom expressed wariness of the local Aborigines and offered his revolver to Horatio.[133] According to Hammersley, Tom said that he often warned his father, but "the old man prided himself on being able to manage the blacks ... and said they would never harm him."[134] The Queensland press, still in the massacre's wake, suggested that Wills, "now a Queenslander", be asked to captain the Queensland cricket team.[135]

Wills never articulated a reason for the massacre, but his brother Cedric wrote years later that the it was an act of revenge for an attack made on local Aborigines by squatter Jesse Gregson. He quoted Tom as saying, "If the truth is ever known, you will find that it was through Gregson shooting those blacks; that was the cause of the murder."[132]

For many years after the massacre, Wills experienced flashbacks, nightmares and an irritable heart—features of what is now known as post-traumatic stress disorder. As a consequence, he increased his drinking in an attempt to blot out memories and alleviate sleep disturbance.[136] Wills' sister Emily wrote of him two months after the massacre: "He says he never felt so changed in the whole course of his life".[137]

Loss of favour and expulsion

Hypervigilant, Wills slept only three hours a night with a rifle beside his bed and watched for signs of another attack.[138] He began to rebuild the station pending the arrival of his uncle, William Roope, who took control of Cullin-la-Ringo in December 1861. They fought constantly and Roope soon left the property as a result of Wills acting "exceedingly ill" to him.[139] The realities of the outback were starting to defeat Wills. He went blind for weeks after contracting "sandy blight".

He returned to Melbourne in January 1863 to captain Victoria against New South Wales on the Domain in Sydney. The match turned into a riot when the crowd invaded the field after a dispute over the Victorian umpire's dismissal of a New South Wales batsman. Wills, leading his men from the Domain, was struck in the face by a stone, and Victorian professionals George Marshall and William Greaves fled Sydney for Melbourne, reducing the team to nine players. Wills took eight wickets and was the top run-scorer in both innings (25* and 17*), but Victoria lost by 84 runs. The Melbourne media castigated Wills for allowing the game to continue and called him a turncoat when evidence surfaced that he agreed to play for New South Wales in the weeks leading up to the match. He denied all accusations and wrote in an angry letter to The Sydney Morning Herald: "I for one do not think that Victoria will ever send an Eleven up here again."[140] Back in Victoria, he became engaged to Skipton farm girl Julie Anderson, a friend of the Wills family. Her name does not appear in any of Wills' surviving letters; he rarely mentioned the women he courted, let alone his feelings towards them.[141] Wills stayed in Geelong for the start of the 1863 football season, blithely breaking his promise to return to Cullin-la-Ringo, much to the dismay of his mother and the holding's trustees.[142]

Wills finally headed back to Queensland in May and was sworn in as a Justice of the Peace upon arrival in Brisbane.[143] Over the next few months, he reported at least three murders of local settlers by Aborigines, including that of a shepherd on Cullin-la-Ringo.[144] He engaged in a series of verbal altercations with government officials over the need for protection from Aboriginal attacks, and scorned "Brisbane saints" for sympathising with the plight of Aborigines in the Nogoa region.[145] With the cricket season approaching, Wills agreed to captain Queensland against New South Wales, and then left the station to lead a Victorian XXII against George Parr's All-England Eleven in Melbourne.[146] In awe of his dash across the continent to play cricket, the English thought it a madman's journey.[147] Wills failed to reach Melbourne in time but joined the visitors on their tour of Victoria.[148]

The period of late 1863 and early 1864 saw a climax of Wills' domestic troubles.[149] His engagement to Julie Anderson was broken off, possibly due to his womanising.[150] Incensed by his long absences from Cullin-la-Ringo and flimsy excuse-making, the trustees exposed Wills as squandering family finances on alcohol while claiming it as station expenditure, and demanded that he stay in Victoria to answer for the property's runaway debt.[151] In response, Wills left Australia and joined George Parr's XI on a month-long tour of New Zealand. He umpired the first match in Dunedin before strengthening various local sides.[152] On his return to Australia Wills was dismissed from Cullin-la-Ringo.[153]

Melbourne to Geelong

Wills stayed at "Belle Vue" with his mother and sisters.[154] Family correspondence from the winter of 1864 reveals that Wills had a "wife"—a "bad woman" according to Emily. It is likely a reference to the already-married Sarah Barbor (née Duff), who Wills called his "housekeeper". Born in Dublin, she is a mysterious figure in Wills' story, but is known to have remained his lifelong partner. The de facto nature of their relationship, and even Barbor's existence, were probably kept secret from Wills' mother for a number of years.[155]

The laws of football were reviewed by the Melbourne Football Club in May 1865; Wills seconded a failed proposal to add a rugby-style crossbar to the goal posts.[156] For the rest of the season he played for and often captained Melbourne and Geelong, two of the game's most powerful clubs. At the end of a winter beset with public brawls over which team "owned" him, Wills moved to Geelong for the remainder of his career, prompting Bell's Life in Victoria to report that Melbourne had lost "the finest leader of men on the football field".[157] The following year, when the running bounce and other rules were formalised at a meeting of club delegates under the chairmanship of H. C. A. Harrison, Wills was not present; his move to Geelong had rendered him peripheral to the process of rule-making in Melbourne.[158]

Intercolonial cricket contests between Victoria and New South Wales resumed at the MCG on Boxing Day 1865, nearly three years since the Sydney riot of 1863. Victoria suffered the defection of Sam Cosstick, William Caffyn and other professionals due to pay disputes with the MCC. Brimming with imported talent and captained by Englishman Charles Lawrence, New South Wales was tipped to win. Wills, leading the weakened Victorian side, took 6 wickets and contributed 58—the first half century in Australian first-class cricket—to 285, an unprecedented total in intercolonial cricket. Victoria won in an innings.[159] Accusations of Wills' "shying" with the cricket ball failed to endanger his status as a folk hero and "a source of eternal hope" for Victoria.[160]

His recklessness inspired lines in the 1866 poem "Ye Wearie Wayfarer" by Adam Lindsay Gordon. Rhyming "Wills" with "spills", he goes on to say:[161]

No game was ever yet worth a rap,

For a rational man to play,

Into which no accident, no mishap,

Could possibly find its way.

Aboriginal cricket team

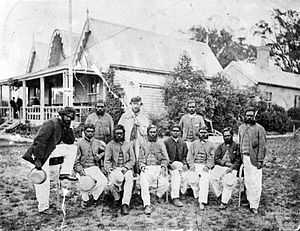

In May 1866, the minute book of the Melbourne Cricket Club featured an unusual request: Roland Newbury, the club's pavilion keeper, wanted "use of the ground for two days ... for purpose of a match with the native black eleven".[162] It was the first intimation of a cricket match between the MCC and an Aboriginal team from Victoria's Western District.[163] The motive behind the match, scheduled for late December, was a financial one, and in August, Wills agreed to coach the team. Wills' personal reasons for accepting the role remain a mystery, but his need for money was likely a factor.[164] This was to mark the beginning of his transition from amateur to professional sportsman.[165]

Wills travelled inland in November to Edenhope and Harrow to convene the players from local pastoral properties, where they worked as station hands.[166] One of their employers, William Hayman, acted as the team's manager and "protector".[167] They were mostly Jardwadjali men who shared common vocabulary with the neighbouring Djab wurrung people, which enabled Wills to use the Aboriginal language he learnt as a child.[168] From their training ground at Lake Wallace, Wills, in a "tactical strike", boasted to the Melbourne press of the team's powers, especially the batting of Mullagh,[e] spurring an anxious MCC to recruit players from outside the club.[169] Public sympathy was with the Aborigines when they arrived in Melbourne and 8,000 spectators flocked to the MCG on Boxing Day to witness the match.[170] Wills captained the team in a losing struggle and afterwards spoke defiantly against the MCC's "treachery".[171]

It is unknown if Wills reflected on the broader social impact of the enterprise.[172] Some of his contemporaries were shocked that he would associate with Aborigines in the shadow of his father's death.[173] Others, such as this letter writer in The Empire, called him a hero:[174]

Although you may not be fully aware of the fact, allow me to tell you that you have rendered a greater service to the aboriginal races of this country and to humanity, than any man who has hitherto attempted to uphold the title of the blacks to rank amongst men.

While Melbourne was transfixed by the Aboriginal team, the intercolonial contest—usually the highlight of the season—failed to excite public interest, and Victoria's loss in Sydney was ascribed to Wills' absence.[175] The team embarked on a tour of Victoria, improving as they went. After an easy win in Geelong, Wills, without warning his mother, took the team to "Belle Vue".[176] Back in Melbourne in mid-January, two of the Aborigines, Bullocky and Cuzens, joined Wills in representing Victoria against a Tasmanian XI.[177] The team's successes provoked pangs of guilt over past mistreatment of Aboriginal people, and Wills became the single point through which colonial society debated European settlement and future relations between the races.[178] His status as a 'native' (a native-born Australian) blurred the distinction between him and his team of Aboriginal 'natives'.[179] The link was strengthened when he spoke in "their own lingo".[180] The "team jester" Jellico teased Wills: "He too much along of us. He speak nothing now but blackfellow talk."[181]

Plans were drawn up for a tour through the colonies and overseas, and in February the team departed for Sydney.[182] English cricketer Charles Lawrence saw lucrative potential in the tour and invited the team to stay at his hotel on Manly Beach.[183] The first match against his club at the Albert Ground in Redfern came to a dramatic halt when Wills, after having led the Aborigines onto the field, was arrested and briefly gaoled for a breach of contract.[184] He had been maneuvering to take over as manager, and was in direct competition with the promoter of the tour, entrepreneur W. E. B. Gurnett.[185] Gurnett turned out to be a con artist, leaving the team stranded and dashing any hope of a trip to England.[186] Lawrence set up a "benefit" match, and by the end of the tour's New South Wales leg, had worked his way into the team to usurp Wills as captain.[187] No longer feted by the media, they made their way back to Victoria in May, and Wills was playing football within two weeks of his Geelong homecoming.[188] It has been said that he exercised a "bad influence" upon the Aborigines with his drinking habit.[189] Four players died over the course of the tour; at least one death, that of Watty, was officially linked to alcohol.[190]

The surviving members formed part of the Aboriginal team which Lawrence took to England in 1868, ten years before the first Australian XI classed as representative went overseas.[191] Wills resented Lawrence for reviving the team without him; his exclusion has been called the tragedy of his sporting career.[192]

Ambiguous professional

Without any career prospects outside of sport, Wills joined the MCC as a professional cricketer at the start of the 1867–68 season, however he wasn't openly referred to as such. Instead, the club devised the title of 'tutor' in order for him to maintain the prestige of his amateur background.[193]

Played on the MCG, the December 1867 intercolonial cricket match between Victoria and New South Wales ended in a sound victory for the former, principally due to Wills' nine-wicket haul and Richard Wardill's century.[194] Wills had been Victoria's preferred captain for over a decade. Writing in his sports column, Hammersley claimed that, as a paid servant of the MCC, Wills lacked "moral ascendancy" over amateur players.[195] When he lost the captaincy to Wardill, an amateur, on the eve of the March 1869 match against New South Wales, he refused to play under him, or, indeed, anyone else. Wills was widely condemned and the Victorians resolved to go on without him, after which he retracted his impulsive decision. This was the last intercolonial match played on the Domain in Sydney and Victoria recovered from Wardill's diamond duck to win by 78 runs. Wills, in one of his best first-class performances, scalped 7 wickets in a single innings.[195]

Wills announced in early 1869 that he would not play cricket for Victoria again, even if the colony wanted him.[196] He threatened to leave for Cullin-la-Ringo, but his mother, still "very dissatisfied" with him, requested that he stay away from the Queensland property.[197] The MCC took Wills back and he continued to act as a tutor with the club.[198] Members of the Aboriginal team, Mullagh and Cuzens, joined him as paid bowlers.[199] Barred from having Wills in matches against the MCC, Geelong was allowed to field an extra five men to make up for his loss.[198]

No-ball plot and downfall

For Mr. Wills to no-ball Mr. Wardill for throwing is like Satan reproving sin.—William Hammersley[200]

Hardly a year had passed since Wills' return to Australia in 1856 without public comment on his suspect bowling action.[201] In February 1870, Wills captained Victoria to a 265-run win over New South Wales at the MCG. The match was memorable for the appearance of Twopenny, an Aboriginal paceman who was said to have been recruited by New South Wales captain Charles Lawrence as a foil to Wills' "chucks".[202] Comparing the two, the Melbourne press hypocritically defended Wills: "Undoubtedly Wills throws sometimes, but there is some decency about it, some disguise."[203] In March, the Victorian team trounced a Tasmanian XVI in Launceston under Wills' leadership, though not without criticism of his bowling action.[204] The accusations of Wills' throwing were growing louder, and Hammersley, the self-appointed defender of standards in colonial sport, emerged as his most severe critic.[205] In the face of a looming crisis in his career, Wills openly admitted to throwing in his 1870–71 Australian Cricketers' Guide, and in so doing taunted his enemies to stop him.[206]

"If I cannot hit your wicket or make you give a chance soon, I'll hit you and hurt you if I can. I'll frighten you out."

A villainous Wills was held as inciting a plague of throwing and corrupting younger bowlers.[208] Throwing allowed him to increase pace, and he was criticised for introducing a style of fast bowling designed to injure and intimidate batsmen.[207] Nonetheless, the Victorian team elected him as captain for the March 1871 intercolonial match against New South Wales, held at the Albert Ground in Sydney. Wills' first innings top score of 39* was offset by his drunkenness on the field and reluctance to bowl for fear of being called. Victoria won by 48 runs.[209] Soon after the game, Wills was no-balled for throwing for the first time in a club match.[207] Rumour spread that it was the result of a conspiracy against him.[210]

A series of superb performances in club cricket removed any doubt that Wills would play for Victoria in the next intercolonial match against New South Wales, scheduled for 30 March 1872 on the MCG.[211] Before the game, representatives from both colonies met and signed a bilateral agreement designed to call Wills. When he opened the bowling, the umpire no-balled his first ball. Wills became the first cricketer to be called for throwing in a major Australian match. Two more balls were ruled as throws in two overs, and Wills did not bowl again.[212] He was again no-balled when Victoria played and lost to a combined XIII from New South Wales, Tasmania and South Australia late in 1872.[213]

Hammersley's campaign to see Wills banished from intercolonial cricket was seemingly achieved, and the two engaged in a bitter exchange of public letters, ending their relationship.[214] Wills implied that Hammersley was behind the no-ball plot, and protested that he and other Englishmen were out to oppress native-born Australians.[215] Hammersley, feeling vindicated, wrote that Wills' demise would restore order to colonial cricket. He closed:[216]

You are played out now, the cricketing machine is rusty and useless, all respect for it is gone. You will never be captain of a Victorian Eleven again, ... Eschew colonial beer, and take the pledge, and in time your failings may be forgotten, and only your talents as a cricketer remembered. Farewell, Tommy Wills.

Grace and resurrection

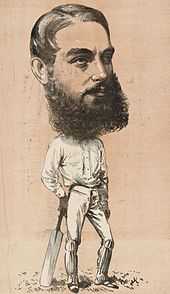

W. G. Grace, the Victorian era's most famous cricketer, brought an English team to Australia in 1873–74. Wills was desperate to play for Victoria against Grace and rival cricketing factions fought over his possible inclusion. Hammersley's role on the selection committee ensured his omission.[217] Wills toured with the team, playing for local sides.[218] Irked by his constant presence, Grace remarked that he appeared to regard himself as a representative of the whole of Australia.[219] It was assumed that, on his homeward journey, Grace would play a final match in the South Australian capital of Adelaide, but he bypassed the city when Kadina, a remote mining town on the Yorke Peninsula, offered him more money. Wills coached the Kadinians.[220] Played in an open, rock-strewn plain of baked earth, the game was little more than a farce. Wills made a pair and Grace later wrote derisively of the "old Rugbeian" as a has-been.[221] Grace neglected to mention that Wills bowled him, ending with 6/28.[222]

In Geelong, Wills was still a celebrated figure, though he seemed discontented, seeking any chance to earn money through cricket in the major cities.[223] As a veteran footballer, Wills maintained that he founded the sport in Victoria, what he called "the king of games".[224] He continued to suggest rule changes, such as the push in the back rule to curb injuries, and, as captain of Geelong, had shaped the sport's playing style.[225] Facing a severe loss in Ballarat, he pioneered the tactic of flooding by ordering his men to flood the backline to prevent Ballarat from scoring. He then told them to waste time and deliberately kick the ball out of bounds amid riotous cries from the crowd.[226] In a rare act of diplomacy, Wills quelled on-field fighting after another rival club used his "unchivalrous tactics" against Geelong.[227] Wills played his last game of football in 1874.[228]

Wills returned to the public eye with the release of his 1874–75 Australian Cricketers' Guide. He pontificated on the ailing Victorian side's need for a new captain: "... no one reading his words could mistake its intent—what Victoria needed was Tom Wills."[229] For the first time since his demise, Wills was under consideration for the next intercolonial match against New South Wales. Noting his faded skills and dark reputation, the Melbourne press lamented, "there is some sentimental notion afloat that as a captain he is peerless."[230] Pessimism gave way to hope as Wills promised a victory, and in February 1876 he led the Victorians onto Sydney's Albert Ground. He went for 0 and 4 and failed to pick up a wicket despite keeping himself on longer than any other Victorian bowler. The media blamed him for Victoria's 195-run loss.[231] In turn, he laid the blame on his team-mates.[232]

By 1877, Wills' cricket "had become a series of petty disputes in petty games" of "ever-deteriorating standards."[233]

Drifting to the margins

Despite his continued slide into debt, he donated a silver trophy for a Challenge Cup between Geelong, Ballarat and clubs of the Western District.[234] He also supported the Geelong branch of the Australian Natives' Association, which he co-founded and served in the capacity of vice-president until it dissolved in July 1876.[235]

From 1873 to 1876 he served as Geelong's vice-president, and in 1877 was appointed as one of three Geelong delegates after the formation of the Victorian Football Association (VFA), but was dropped soon after for unknown reasons.[236] Acting as a central umpire during the 1878 VFA season, he defended his adjudication of a match between Carlton and Albert Park in what would be his final public letter.[237] Geelong won the 1878 VFA premiership; that year, Wills, broke and hounded by debt collectors, moved with Sarah Barbor to Emerald Hill (South Melbourne), and his role at the club was diminished.[238]

Wills made scant appearances for the South Melbourne Cricket Club, performing poorly.[239] Inspired by his Rugby experience, he convinced the club to open its ground to football in winter on the basis that it would improve the turf.[240] Geelong did likewise, and football adapted to an oval-shaped playing field.[241] By 1880, the sport had spread throughout the Australian colonies, and up to 15,000 spectators attended major matches of the season in Melbourne, the world's largest football crowds hitherto recorded.[242]

Final year and death

Wills moved with Sarah to Heidelberg on the outskirts of Melbourne, rarely leaving the village for the remainder of his life.[243] His alcoholism worsened, as did Sarah's, also a heavy drinker.[244] He coached the local cricket team, and, on 13 March 1880, played for the side in his last recorded game. His "chucks" were still noted.[245] In his last surviving letters, sent two days later to Cedric and Horace on Cullin-la-Ringo, he wrote of Heidelberg as a place of exile—"I'm out of the world here"—and fantasised about escaping to Tasmania. Begging for money to help pay off debts, he promised, "I will not trouble any of you again".[246]

Isolated and disowned by most of his family, Wills had become, in the words of cricket historian David Frith, "a complete and dangerous and apparently incurable alcoholic".[247] Contrary to legend, Wills was never incarcerated in a lunatic asylum.[248] He started to show signs of delirium tremens in late April, including paranoid delusions, and Sarah, fearing that a calamity was at hand, admitted him to the Melbourne Hospital on 1 May to be kept under restraint. Wills absconded soon after, returned home and the next day committed suicide by stabbing a pair of scissors into his heart three times.[249] The inquest, on 3 May, presided over by the city coroner Richard Youl, found that Wills "killed himself when of unsound mind from excessive drinking".[250] Wills was buried the following day in an unmarked grave in Heidelberg Cemetery at a private funeral attended by only six people: his brother Egbert, sister Emily and cousin H. C. A. Harrison; Harrison's sister Adela and her son Amos; and MCC cricketer Verney Cameron.[251] His death certificate declared that his parents were unknown.[252] When asked by a journalist about her son, Elizabeth Wills is reported to have denied that Tom ever existed.[f]

Personality

Academic Barry Judd wrote in 2007:[253]

Tom Wills exists as a spectral figure, a ghost inhabiting the margins of written history; ... [his] transient appearance in historical memory indicates little of whom he was, what he thought or why he did the things he did.

Wills struck his contemporaries as peculiar and at times narcissistic, with a prickly temperament, but also kind, charismatic and companionable.[254] Always embroiled in controversy, he seemed to lack an understanding of how his words and actions could repeatedly get him into trouble.[255] Through his research, journalist Martin Flanagan concluded that Wills was "utterly bereft of insight into himself",[256] and football historian Gillian Hibbins described Wills as "an overbearing and undisciplined young man who tended to blame others for his troubles and was more interested in winning a game than in respecting sporting rules."[257] Wills' family and peers, though angered by his misbehaviour, frequently forgave him.[258] It is unlikely that he sought popular favour, but his strong egalitarian streak helped solidify his reputation as a man of the people.[259] This affection, coupled with an understanding of his waywardness, found expression in the public motto: "With all thy faults I love thee still, Tommy Wills".[260]

As a young adult back in Australia, Wills developed a peculiar stream of consciousness style of writing that sometimes defied syntax and grammar.[261] His letters are laced with puns, oblique classical and Shakespearean allusions, and droll asides, such as this one about Melbourne in a letter to his brother Cedric: "Everything is dull here, but people are kept alive by people getting shot at in the streets".[262] The overall effect is one of "a mind full of energy and histrionic ideas without a centre".[263]

He could be dismissive, triumphant and brazen all within a single sentence. Whatever his inner world was, he rarely let it be known. Lines of argument or considered opinion were not developed. His stream of thought was in rapid flux and a string of defiant jabs. To give emphasis he underlined his words with a flourish. His punctuation was idiosyncratic. Language was breathless and explosive and he revelled in presenting himself and his motives as mysterious.—Greg de Moore[168]

Wills' provocative and laconic speaking manner reflected aspects of his written language.[264] In one of his borderline "thought disordered" letters, it is evident that at times he entered a state of depersonalisation: "I do not know what I am standing on ... when anyone speaks to me I cannot for the life of me make out what they are talking about—everything seems so curious."[265] In 1884, Hammersley compared Wills' incipient madness and fiery glare to that of Australian poet Adam Lindsay Gordon.[266] Wills' mental instability is a source for medical speculation. Epilepsy has been suggested as a possible cause of his perplexed mental state, and a variant of bipolar illness may account for his disjointed thinking and "flowery and confused" writings.[267]

In 1923, Wills' old cricket cap was found by the Melbourne Cricket Club and put on display in the Block Arcade, prompting Horace to reflect on his brother: "[Tom] was the nicest man I ever met. Though his nature was care-free, amounting almost to wildness, he had the sweetest temper I have seen in a man, and was essentially a sportsman."[268]

Legacy

| “ | He was buried on the hill top at Heidelberg, overlooking that green valley which, eight years later, Streeton and Roberts and the painters of the Heidelberg School would depict in summer colours. A third generation Australian—then a rarity—he had often expressed in football and cricket a version of the national feeling which these artists were to express in paint, and he had been quietly proud that the football game he did so much to shape was often called 'the national game'. | ” |

| —Geoffrey Blainey, A Game of Our Own[269] | ||

Wills fell into relative obscurity in the decades following his death. Foremost a cricketer to his contemporaries, he is now mostly remembered as a pioneer of Australian football.[270] His story has been called one of Australia's most powerful national narratives, commensurate with the Ned Kelly legend.[109] The mythologising of Wills, in particular his upbringing with Aborigines, dates back to early twentieth century when the first attempt was made to write his biography.[271] It wasn't until 2008 that a definitive biography was published, written by Sydney psychiatrist Greg de Moore.[272]

His anonymous gravesite was restored in 1980 with a headstone erected by the Melbourne Cricket Club and by public subscription. The epitaph recognises Wills as the "Founder of Australian football and champion cricketer of his time".[273] He was inducted into the Sport Australia Hall of Fame in 1989,[274] and was made an inaugural member of the Australian Football Hall of Fame upon its creation in 1996. The International Cricket Hall of Fame in Bowral has an exhibit on Wills' life, in particular his role as captain-coach of the Aboriginal cricket team.

The Tom Wills Room in the Great Southern Stand of the MCG serves as a venue for corporate functions.[275] A statue outside the MCG, sculptued by Louis Laumen and erected in 2001, depicts Wills umpiring the famous 1858 football match between Melbourne Grammar and Scotch College. The plaque reads that Wills:[276]

... did more than any other person – as a footballer and umpire, co-writer of the rules and promoter of the game – to develop Australian football during its first decade.

Round 19 of the 2008 AFL Season was named Tom Wills Round to mark the 150th anniversary of the Melbourne Grammar and Scotch College match. The two schools played in a curtain raiser at the MCG ahead of the round's opening game between Melbourne and Geelong.[277] That same year, Victoria's busiest freeway interchange, the Monash–EastLink interchange in Dandenong North, was named the Tom Wills Interchange.[278] Tom Wills Oval, inaugurated in 2013 at Sydney Olympic Park, serves as the training base for the Greater Western Sydney Football Club of the AFL.[279]

Wills has inspired numerous works in Australian popular culture, including musical pieces by singer-songwriters Mick Thomas and Neil Murray,[280] as well as The Holy Sea.[281] Martin Flanagan's 1998 historical novel The Call is a semi-fictional account of Wills' life. In it, Wills is cast as a tragic sporting genius,[282] and the dingo is used to symbolise his identity as an "ambiguous creature" caught between indigenous and non-indigenous Australia.[283] It was adapted into a stage play by Bruce Myles in 2004.[284] Plans for a feature film on Wills were made in 1989 but later abandoned.[284]

Marngrook theory

There is no evidence that Wills played Marngrook, an Aboriginal game that has superficial similarities with Australian rules football; however, the connection may have had some influence. In James Dawson's first-hand account of Aboriginal ball games, the Djab wurrung word for football is recorded as Min'gorm.[285] Therefore, it is likely that Wills' childhood friends played a type of Aboriginal football, or at the very least knew of such a game.[286] Since the 1980s, it has been suggested that Wills played the game growing up, and that this may have had an influence on his rules for Australian football.[287] Lawton Wills Cooke, the grandson of Tom's brother Horace, reported that "Tom played some form of football with Aboriginal kids. We have no documents to prove this, but there is a family story that they kicked a possum skin sewn up in the shape of a ball."[288] This claim was disputed by T. S. Wills Cooke in his published history of the Wills family.[289]

Based on its connection to Wills, Moyston is the self-proclaimed birthplace of Australian football, and is home to a monument commemorating his upbringing in the area playing Marngrook.[290] In 2008, the year of Australian football's 150th anniversary celebrations, Wills' link to Marngrook was hotly debated in the national media, amounting to a controversy dubbed "football's history wars".[291] The AFL's official history of the game calls the theory a "seductive myth".[292] In response, Flanagan wrote an essay addressed to Wills, arguing that he must have known Aboriginal games as it was in his nature to play: "There's two things about you everybody seems to have agreed on—you'd drink with anyone and you'd play with anyone."[293]

See also

- List of Australian rules footballers and cricketers

- List of cricketers called for throwing in major cricket matches in Australia

Footnotes

a. ^ Tom Wills' birthplace is a matter of some conjecture as there is a dearth of reliable archival information on the subject, and the precise whereabouts of his parents are difficult to pinpoint during the period around 1835.[294] Molonglo is given as his birthplace in an 1869 biographical piece in which William Hammersley, the author, states that Wills had furnished him with notes.[295] A common alternative is Parramatta.[294] When Victorians claimed Wills as one of theirs, he liked to boast that he was a "Sydney man"—a reference to the colony of his birth.[296]

b. ^ Tom had eight siblings: Emily Spencer Wills (1842–1925), Cedric Spencer Wills (1844–1914), Horace Spencer Wills (1847–1928), Egbert Spencer Wills (1849–1931), Elizabeth Spencer Wills (1852–1930), Eugenie Spencer Wills (1854–1937), Minna Spencer Wills (1856–1943) and Hortense Sarah Spencer Wills (1861–1907).[297]

c. ^ Tom Wills and H. C. A. Harrison shared Sarah Howe as a grandmother.[298] Harrison was born ten months after Wills in New South Wales and as a young boy overlanded to the Port Phillip District, where he often visited the Wills family at Lexington.[113] They became brothers-in-law in 1864 when Harrison married Emily Wills.[299]

d. ^ George Augustus Robinson, the Chief Protector of Aborigines in the Port Philip District, listed Horatio as having murdered several Aboriginal men and women. The closest Horatio came to admitting that he had killed Aborigines was in a letter to Governor Charles La Trobe: "... we shall be compelled in self defence to measures that may involve us in unpleasant consequences".[300]

e. ^ The Aborigines went by sobriquets given to them by their white employers in the Western District.[301] Named after the station where he worked, Mullagh's real name was Unaarrimin.[302]

f. ^ This story was related in the following piece of Wills family oral history: "Elizabeth Wills refused to attend [the funeral] nor would she acknowledge Tom after his death as she was very religious and considered [suicide] a great sin. ... A reporter asked Elizabeth about her son. "Which son?" she asked. "Thomas" said the reporter. "I have no son called Thomas" was the old lady's reply".[303]

References

- ↑ de Moore 2005, p. 371.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 326.

- ↑ Mandle 1976.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 3, 6; Howard & Larkins 1981, p. 38.

- ↑ Wills Cooke 2012, p. 6.

- ↑ Wills Cooke 2012, p. 13.

- ↑ Wills Cooke 2012, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 de Moore 2011, p. 8.

- ↑ McKenna 1996, pp. 23–25.

- ↑ Judd 2007, p. 114; de Moore 2011, p. 8.

- ↑ Wills Cooke 2012, p. 173; de Moore 2011, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Molony 2000, pp. 137–139; Wills Cooke 2012, p. 37.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 190; Judd 2007, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 de Moore 2011, p. 15.

- ↑ Wills Cooke 2012, p. 37, 53; de Moore 2011, p. 10.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 165.

- ↑ Hibbins & Mancini 1987, p. 79.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 322–323.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 331–332; Wills Cooke 2012, pp. 37–39.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 14.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 15–16; Judd 2007, p. 111.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 16.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 18.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 de Moore 2011, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 52.

- ↑ Judd 2007, pp. 133–135.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 23.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 24.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 43.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 40, 44.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 de Moore 2008, p. 37.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 38.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 65; Gorman 2011, p. 131.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 47.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 43; de Moore 2011, p. 32.

- ↑ Wills Cooke 2012, pp. 174–176; de Moore 2011, p. 331.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 43.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 45; de Moore 2011, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 48.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 de Moore 2008, p. 49.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 50; de Moore 2011, p. 46.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, pp. 51–55.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 50, 57.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 28.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Hammersley, William (1869).

Mr Thomas W. Wills: A Biographical Sketch. Wikisource.

Mr Thomas W. Wills: A Biographical Sketch. Wikisource. - ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 40–42, 47–48.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 334.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 25.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 33.

- ↑ Inglis 1993, p. 127.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 44.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 50.

- ↑ Flanagan 2008, p. 546; de Moore 2011, pp. 51–52, 57.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 52–53, 334.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 51.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 53.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 de Moore 2008, p. 32.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 54.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 55–57.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 64, 113.

- ↑ de Moore 2012, p. 16.

- ↑ Mandle 1973, p. 225; Hibbins 2013, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 57–58.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 58.

- ↑ Clowes 2007, pp. 6–7; de Moore 2011, p. 60.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 62.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 78–79.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 80.

- ↑ Judd 2007, pp. 141–142; de Moore 2011, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 85–86.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 72–76.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 83–84.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 72.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 86.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 92, 95–96, 105.

- ↑ Judd 2007, p. 152, 335.

- ↑ Hibbins & Mancini 1987, pp. 118–119.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 77–78.

- ↑ Blainey 2003, p. 8; de Moore 2011, p. 119.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 2–3.

- ↑ Bell's Life in Victoria, 10 July 1858.

- ↑ Hess 2008, p. 8; de Moore 2011, p. 87.

- ↑ Blainey 2003, pp. 28–30, 207.

- ↑ Judd 2007, p. 135.

- ↑ Blainey 2003, p. 22; Hess 2008, p. 8, 10.

- ↑ Blainey 2003, pp. 15–18.

- ↑ Hibbins & Ruddell 2009, p. 9.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 91.

- ↑ Hibbins & Ruddell 2009, p. 13; Pennings 2013, p. 1.

- ↑ Hess 2008, p. 16; de Moore 2011, pp. 91–92.

- ↑ Hibbins Ruddell, p. 5.

- ↑ Hess 2008, p. i.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 de Moore 2011, p. 101.

- ↑ Hibbins Ruddell, p. 7.

- ↑ Hibbins Ruddell, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 325.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 96–97.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 106.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 106–107.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 107.

- ↑ Judd 2007, p. 142.

- ↑ Clowes 2007, p. 10.

- ↑ The Sydney Morning Herald, 27 January 1859.

- ↑ Hibbins & Ruddell 2009, pp. 18–20.

- ↑ Hibbins & Ruddell 2009, p. 8, 12.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 Flanagan 2011.

- ↑ Hibbins & Mancini 1987, p. 43; Hess 2008, pp. 41–43.

- ↑ Sandercock & Turner 1982, p. 27.

- ↑ Hibbins & Ruddell 2009, p. 12.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 Blainey 2003, p. 68–69.

- ↑ Pennings 2012, p. 29–31.

- ↑ Hibbins & Ruddell 2009, p. 8; de Moore 2011, pp. 104–105.

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 de Moore 2011, pp. 104–105.

- ↑ Blainey 2003, p. 207.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ 119.0 119.1 de Moore 2011, p. 115.

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 de Moore 2011, p. 116.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 117.

- ↑ 122.0 122.1 de Moore 2011, p. 121.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 118.

- ↑ Reid 1981, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Sayers 1967.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 122.

- ↑ Reid 1981, pp. 74–75; de Moore 2011, p. 130.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 125, 130.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 126.

- ↑ 130.0 130.1 de Moore 2011, p. 131.

- ↑ de Moore, p. 130, 341.

- ↑ 132.0 132.1 de Moore 2011, p. 134.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, pp. 129–130.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 133.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 128.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 136–137; de Moore 2008, pp. 214–217.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 136.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 137; de Moore 2012, p. 17.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 141–142.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 149–151.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 153–155, 171.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 155.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 156.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, pp. 131–132; de Moore 2011, pp. 157–158.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 159.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 160.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 161.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 197.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 163–164.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 222; de Moore 2011, p. 161.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 167.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 169–170.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 171–172, 345–346.

- ↑ Hibbins & Ruddell 2009, p. 21.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 173, 176–177.

- ↑ Hibbins & Ruddell 2009, p. 22; de Moore 2011, p. 181.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 178–180.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 85, 89; de Moore 2011, pp. 179–180.

- ↑ Blainey 2003, p. 210.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 136.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 181.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 137.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 182–183.

- ↑ Mallett 2002, pp. 18–20.

- ↑ Mallett 2002, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ 168.0 168.1 de Moore 2011, p. 184.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 184; de Moore 2008, p. 140.

- ↑ Mallett 2002, p. 22; de Moore 2011, pp. 186–187.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 188–189.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 209.

- ↑ de Moore 2012, p. 17.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 198–199.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 190.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 191.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 197–198; de Moore 2008, pp. 146–147.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 152.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 185.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 196–197.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 192, 200–201.

- ↑ Mallett 2002, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, pp. 154–159.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 348.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 205.

- ↑ Mallett 2002, p. 28; de Moore 2011, p. 206.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 207.

- ↑ Mallett 2002, p. 29.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, pp. 240–241; Mallett 2002, p. 28.

- ↑ Mallett 2002, p. 25, 29.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 214; Flanagan 2008, p. 548.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 210–212.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 214.

- ↑ 195.0 195.1 de Moore 2011, pp. 218–219.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 222.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 232.

- ↑ 198.0 198.1 de Moore 2011, pp. 222–223.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 142.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 230.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 76.

- ↑ Mallett 2002, p. 79.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 224.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 225.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 77; de Moore 2011, p. 231.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 85.

- ↑ 207.0 207.1 207.2 de Moore 2008, p. 84.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 231–232.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 233-234.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 241.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 241–242.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 244.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 242.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 87.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 246–247.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 251.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 253.

- ↑ Wills Cooke 2012, p. 194.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 254–255.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 262–263.

- ↑ Molony 2000, p. 143.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 272–273.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 271.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 268.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 268–269.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 353.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 270.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 274.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 276.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 277.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 278.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 282.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 354.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 279.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 282, 353.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 289–290.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 290.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 288–289.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 289.

- ↑ Hess 2008, p. 44.

- ↑ Blainey 2003, p. 108.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 294–296.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 301.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 297.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 299–301.

- ↑ Frith 2011, p. 167.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 318.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, pp. 266–268.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 308–310.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 310.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 291.

- ↑ Judd 2007, p. 121.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 3; de Moore 2011, p. xvii; Blainey 2003, p. 8.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 193.

- ↑ Judd 2007, p. 151.

- ↑ Hibbins 2008, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 108.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 78, 237.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 235.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. xvii, 69.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 184.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 69.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 185.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 184; de Moore 2011, p. 66.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 299.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 68, 335.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 317–318.

- ↑ Blainey 2003, p. 211.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 108.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, pp. 4–5, 100.

- ↑ Watt, Jarrod (28 July 2008). "Investigating the death of the father of football", ABC South West Victoria. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ↑ Thomas Wentworth Wills, Monument Australia. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ↑ Thomas Wills, Sport Australia Hall of Fame. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ↑ Tom Wills Room, Melbourne Cricket Ground. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ↑ First Australian Rules Game, Monument Australia. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- ↑ Harris, Amelia (7 August 2008). "Original and still the best", Herald Sun. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ↑ Ballantyne, Adrian (3 March 2008). "Legend rules the road", Dandenong Leader. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ↑ Tom Wills Oval, Sydney Olympic Park Authority. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ↑ Flanagan, Martin (23 May 2003). "Songs of a defiant heart", The Age. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ↑ Schaefer, René (5 October 2010)."The Holy Sea – Ghosts of the Horizon", Mess+Noise. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ Flanagan, Martin (6 November 1998). The Summer Game. Interview with Amanda Smith. The Sports Factor. ABC Radio National. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ↑ Judd 2007, pp. 154–156, 336.

- ↑ 284.0 284.1 de Moore 2008, p. 4.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 97.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 323.

- ↑ Hibbins & Ruddell 2009, p. 8.

- ↑ Flanagan, Martin (27 December 2008). "A new chapter in the legend of Tom Wills", The Age. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ↑ Wills Cooke 2012, p. 180.

- ↑ Hirst 2010, p. 55.

- ↑ Cazaly 2008.

- ↑ Hibbins 2008, p. 45.

- ↑ Flanagan 2008, p. 543.

- ↑ 294.0 294.1 de Moore 2008, p. 171.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 328.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 81–82.

- ↑ Wills Cooke 2012, p. 250.

- ↑ Hibbins & Mancini 1987, p. 5.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 172–173.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, pp. 11–14.

- ↑ de Moore 2011, p. 192.

- ↑ Mallett 2002, p. 18.

- ↑ de Moore 2008, p. 303.

Bibliography

Books

- Blainey, Geoffrey (2003). A Game of Our Own: The Origins of Australian Football. Black Inc. ISBN 978-1-86395-347-4.

- Clowes, Colin (2007). 150 Years of NSW First-class Cricket: A Chronology. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 9781741750829.

- de Moore, Greg (2011). Tom Wills: First Wild Man of Australian Sport. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74237-598-4.

- Flanagan, Martin (2008). The Last Quarter: A Trilogy. One Day Hill. ISBN 978-0-9757708-9-4.

- Frith, David (2011). Silence of the Heart: Cricket Suicides. Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 9781780573939.

- Gorman, Sean (2011). "A Whispering: Ask not how many; ask why not?". In Ryan, Christian. Australia: Story of a Cricket Country. Hardie Grant Books. pp. 128–135. ISBN 978-174066937-5.

- Hay, Roy (2009). "A Club is Born". In Murray, John. We are Geelong: The Story of the Geelong Football Club. Slattery Media Group. pp. 23–31. ISBN 978-0-9805973-0-1.

- Hess, Rob (2008). A National Game: The History of Australian Rules Football. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-07089-3.

- Hibbins, Gillian; Mancini, Anne (1987). Running with the Ball: Football's Foster Father. Lynedoch Publications. ISBN 978-0-7316-0481-4.

- Hibbins, Gillian (2008). "Men of Purpose". In Weston, James. The Australian Game of Football: Since 1858. Geoff Slattery Publishing. pp. 31–45. ISBN 978-0-9803466-6-4.

- Hibbins, Gillian (2013). "The Cambridge Connection: The English Origins of Australian Football". In Mangan, J. A. The Cultural Bond: Sport, Empire, Society. Routledge. pp. 108–127. ISBN 9781135024376.

- Hirst, John (2010). Looking for Australia: Historical Essays. Black Inc. ISBN 9781863954860.