Tom Simpson

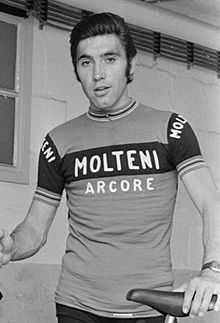

Simpson in 1967 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Thomas Simpson[1] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Nickname | Mr Tom[2] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

30 November 1937 Haswell, County Durham, England | ||||||||||||||||||

| Died |

13 July 1967 (aged 29) Mont Ventoux, Provence, France | ||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 1.81 m (5 ft 11 in)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Weight | 69 kg (152 lb; 10.9 st)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Team information | |||||||||||||||||||

| Discipline | Road and track | ||||||||||||||||||

| Role | Rider | ||||||||||||||||||

| Rider type | All-rounder | ||||||||||||||||||

| Amateur team(s) | |||||||||||||||||||

| - | Harworth & District CC | ||||||||||||||||||

| - | Scala Wheelers | ||||||||||||||||||

| Professional team(s) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1959 | St. Raphaël-Géminiani | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1960–1961 | Rapha-Gitane-Dunlop | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1962 | Gitane-Leroux-Dunlop | ||||||||||||||||||

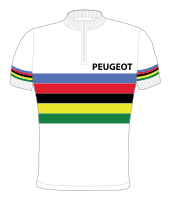

| 1963–1967 | Peugeot-BP-Englebert | ||||||||||||||||||

| Major wins | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Medal record

| |||||||||||||||||||

Thomas "Tom" or "Tommy" Simpson (30 November 1937 – 13 July 1967) was one of Britain's most successful professional cyclists. He was born in Haswell, County Durham and later moved to Harworth, Nottinghamshire. Simpson began road cycling as a teenager before taking up track cycling, specialising in pursuit races. He won a bronze medal for track cycling at the 1956 Summer Olympics and a silver at the 1958 Commonwealth Games.

In 1959 at age 21, Simpson was signed by the French professional road-racing team St. Raphaël-Géminiani. He advanced to their first team (Rapha-Gitane-Dunlop) the following year, and won the 1961 Tour of Flanders. Simpson then joined Gitane-Leroux-Dunlop; in the 1962 Tour de France he became the first British rider to wear the yellow jersey, finishing sixth overall.

In 1963 Simpson moved to Peugeot-BP-Englebert, winning Bordeaux–Paris that year and Milan – San Remo in 1964. In 1965 he became Britain's first world road race champion and won the Giro di Lombardia; this made him the BBC Sports Personality of the Year, the first cyclist to win the award. Injuries hampered much of Simpson's 1966 season. He won two stages of the 1967 Vuelta a España before taking the general classification of Paris–Nice that year.

During the 13th stage of the 1967 Tour de France, Simpson collapsed and died during the ascent of Mont Ventoux. He was 29 years old. The post-mortem examination found that he had mixed amphetamines and alcohol; this diuretic combination proved fatal when combined with the heat, the hard climb of the Ventoux and a stomach complaint. A memorial near where he died has become a place of pilgrimage for many cyclists. Simpson was known to have taken performance-enhancing drugs during his career, when no doping controls existed. Despite this, he is held in high esteem by many cyclists for his character and will to win.

Early life and amateur career

Childhood and club racing

Simpson was born on 30 November 1937 in Haswell, County Durham, the youngest of six children of coal miner Tom Simpson and his wife Alice (née Cheetham).[1][4][5] His father had been a semi-professional sprinter in athletics.[6] The family lived modestly in a small terraced house[4][6] until 1943, when his parents took charge of the village's working men's club and lived above it.[7] In 1950 the Simpsons moved to Harworth on the Nottinghamshire-Yorkshire border, where young Simpson's maternal aunt lived; new coalfields were opening, with employment opportunities for him and older brother Harry (by now, the only children left at home).[6][8][9] Simpson rode his first bike (his brother-in-law's) at age 12, sharing it with Harry and two cousins for time trials around Harworth. Following Harry, Tom joined Harworth and District CC.[10] To upgrade his bike, he delivered groceries in the Bassetlaw district by bicycle and traded with a customer for a better road bike.[10][11] He was often left behind in club races; members of his cycling club nicknamed him "four-stone Coppi" (after Italian rider Fausto Coppi), due to his small stature.[11][12]

Simpson began winning club time trials at his club, but sensed resentment of his boasting from senior members.[13] He left Harworth and District and joined Rotherham's Scala Wheelers.[14][15] Simpson's first road race was as a junior at the Forest Recreation Ground in Nottingham.[16][17][18] After leaving school he was an apprentice draughtsman at an engineering company in Retford (about 10 miles (16 km) from his home in Harworth), commuting by bike as training.[17] He placed well in the 0.5 mi (0.8 km) races on grass and cement, but decided to concentrate on road racing.[17][18] In May 1955 Simpson won the National Cyclists' Union (NCU) South Yorkshire individual pursuit as a junior; the same year, he won the British League of Racing Cyclists (BLRC) junior hill climb championship and placed third in the senior event.[16] His first race as a senior was a second-place finish in the semi-professional Circuit des Grimpeurs in Derbyshire.[19]

Simpson immersed himself in the world of cycling; he wrote to naturalised Austrian rider George Berger, who helped him with his riding position.[20][21] In late 1955, Simpson was suspended from racing after a dispute between the two governing bodies of cycling in Britain (the NCU and the BLRC); both bodies agreed that if any rider committed an offence under the Road Traffic Act, they would incur a suspension. Simpson was caught by police failing to stop at a stop sign, and was banned for six months. During his suspension he dabbled in motorcycle trials, nearly quitting cycling but unable to afford the new motorcycle necessary for progress in the sport.[22][23]

Track years: Olympics, Commonwealths and amateur worlds

Berger told Simpson that if he wanted to be a successful road cyclist, he needed experience in track cycling (particularly the 4000 m individual pursuit).[24] Simpson competed regularly at Fallowfield Stadium in Manchester, where in early 1956 he met amateur world pursuit silver medallist Cyril Cartwright (who thought Simpson had a chance of winning that year's national pursuit championship). Cartwright gave him diet advice, lent him a track bike and developed his technique. Reg Harris, a 1948 Olympic silver medallist, was brought in to train with Simpson.[25][26][27] At the national championships at Fallowfield the 18-year-old Simpson won a silver medal in the individual pursuit, defeating amateur world champion Norman Sheil before losing to Mike Gambrill.[16][28][29]

Simpson began working with his father as a draughtsman at the glass factory in Harworth.[30] He was riding well; although not selected by Great Britain for the amateur world championships, he made the 4,000-metre team pursuit squad for the 1956 Olympics.[31] In mid-September, Simpson competed for two weeks in the Soviet Union against Russian and Italian teams to prepare for the Olympics. The seven-rider contingent began in Leningrad, continuing to Moscow before finishing in Sofia. He was nicknamed "the Sparrow" by the Soviet press because of his slender build.[31] The following month he was in Melbourne for the Olympics, qualifying for the team-pursuit semifinals against Italy; the team was confident of defeating South Africa and France but lost to Italy, taking the bronze medal. Simpson blamed himself for the loss, pushing too hard on a turn and unable to recover for the next.[32][33][34]

There was one name on everyone's lips on that day: "Tom Simpson". There was a buzz in the crowd as he began to climb, you could feel it, and I remember this lad with a shock of hair thundering up the hill past me, carried on a solid wave of excitement. The overall feeling that day was that this was the future, this was the man to watch – Tom Simpson.

After the Olympics, Simpson trained throughout his winter break into 1957.[36] In May, he rode the national 25-mile championships; although he was the favourite, he lost to Sheil in the final. In a points race at an international event at Fallowfield a week later Simpson crashed badly, almost breaking his leg; he stopped working for a month and struggled to regain his form. At the national pursuit championships, he was beaten in the quarter-finals.[37][38] After this defeat Simpson returned to road racing, winning the BLRC national hill-climbing championship in October[39][40] before taking a short break from racing.[41] In spring 1958 he raced in the Daily Herald Trophy at the White Monday Meeting at Fallowfield before racing in Sofia with Sheil for two weeks and winning the national pursuit championship at Herne Hill. In July Simpson won a silver medal for England in the individual pursuit at the Commonwealth Games in Cardiff, losing to Sheil by one-hundredth of a second in the final.[42][43][16]

In September 1958, Simpson competed at the amateur world championships in Paris. Against reigning world champion Carlo Simonigh of Italy in the opening round of the individual pursuit, his wheel got caught in the guttering tyre at the end of the race; when he bunny hopped his bike out, his tyre burst as it hit a crack in the concrete track. Simpson was briefly knocked unconscious and sustained a dislocated jaw; however, he won the race since he crashed after the finish line. Although he was in pain, team manager Benny Foster forced him to race in the quarterfinal against New Zealand's Warwick Dalton as a strategic move favouring Simpson's teammate Sheil (who won the gold medal). Simpson felt that if he had not crashed, the world championship would have been his.[44][45][16] He wanted to turn professional, but needed to prove himself first.[46] Simpson set his sights on the world amateur indoor hour record, and Reg Harris arranged for an attempt at the Oerlikon velodrome in Zürich on 30 November (Simpson's birthday). He failed by 300 m, covering a distance of 43.995 km (27.3 mi) and blaming his failure on the low temperature generated by an ice rink in the center of the velodrome.[47][48][16][49]

After Simpson's failed hour-record attempt, he was invited to a race in East Berlin as part of a British team; upon his return, he decided to move to the continent for a better chance at success.[50] He contacted French brothers Robert and Yvon Murphy (whom he met while racing in Manchester and the Isle of Man), and they agreed that he could stay with them in the Breton fishing port of Saint-Brieuc.[51] His final event in Britain was the Good Friday meeting at Herne Hill, riding motor-paced races against opponents who included reigning world champion Lothar Meister. Simpson won the event and was invited to Germany to train for the 1959 motor-paced world championships, but declined the opportunity in favour of a career on the road. Bicycle manufacturer Elswick Hopper invited him to join their British-based team, but Benny Foster advised him to continue with his plans to move to France.[52]

Move to Brittany

In April 1959, Simpson left for France with two Carlton bikes (one road and one track) and £100 from Carlton in appreciation of his help promoting the company. His last words to his mother before the move were, "I don't want to be sitting here in 20 years' time, wondering what would have happened if I hadn't gone to France". The next day, his National Service papers were delivered; although willing to serve before his move, he later avoided conscription.[48][53][54] When settled with the Murphy family, Simpson began winning local races and attracting attention in criteriums. He was invited to race in the Route de France (an eight-day amateur stage race) by the St. Raphaël-sponsored VC 12 club, who were behind the professional team St. Raphaël-Géminiani. Simpson won the final stage, breaking away from the peloton and holding on for the victory.[55][56][57] After this win, he declined an offer to ride in the Tour de France on an international team.[58] Simpson had contract offers from two professional teams, Mercier-BP-Hutchinson and Rapha (which already had a British cyclist, Brian Robinson); opting for the latter team, on 29 June he signed a contract for 80,000 francs (£80 a month).[59][58][60]

Professional career

1959: Foundations

Simpson's first race as a professional was the Tour de l'Ouest in July. In the opening stage he finished in a breakaway group with teammate Pierre Everaert, who took the leader's jersey. In stage four, a break formed; Simpson tried to bridge the gap for Everaert (who could not manage the pace), winning a sprint finish and taking the leader's jersey. He won the next stage, a 41.6 km (25.8 mi) individual time trial, increasing his lead to about three minutes.[61][62] He lost the lead on the next stage with a puncture,[63] finishing the race in 14th place overall.[16]

In August Simpson competed at the world championships in the 5000 m individual pursuit at Amsterdam's large, open-air velodrome and the road race on the nearby Circuit Park Zandvoort motor-racing track. He placed fourth in the individual pursuit, losing by 0.3 seconds in the quarterfinals. He expected to progress further, and prepared for the 180 mi (289.7 km) road race (eight laps of the track, Simpson's first professional one-day race). After 45 mi (72.4 km) a ten-rider breakaway formed; at 63 mi (101.4 km), Simpson bridged the gap. As the peloton began to close in, he tried to attack. Although he was brought back each time, Simpson placed fourth in a sprint for the best finish to date by a British rider. He was praised by the winner, André Darrigade of France, who thought that without Simpson's work on the front the breakaway would have been caught. Darrigade helped him enter criteriums for extra money.[64][65][66]

Simpson moved up to St. Raphaël-Géminiani's first team, Rapha-Gitane-Dunlop, for the end-of-season classic races. He rode in Paris–Tours, finishing 16th after a bunch sprint,[67] and retired from the Giro di Lombardia with a puncture while in the lead group (his first appearance in one of the five "monuments" of cycling).[68][69] In Simpson's last race of the season, he finished fourth in the Trofeo Baracchi (a two-man team time trial with Gérard Saint) against his boyhood idol, Fausto Coppi; it was Coppi's final race before his death.[70] Simpson finished the season with 28 wins.[66]

1960: Tour debut

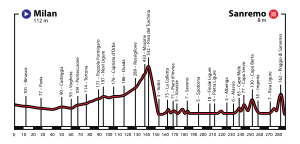

Simpson's first major race of the 1960 season was Milan – San Remo on 19 March, in which the organisers introduced the now-famous Poggio climb to keep the race from finishing with a bunch sprint. Simpson broke clear from a breakaway group over the first climb (the Turchino), leading the race for 45 km (28.0 mi) before being caught. He lost contact over Poggio, finishing in 38th place.[71][72][73] Simpson rode in Paris–Roubaix (the first race to be shown live on Eurovision),[74][75] launching an attack as an early break was caught. He rode at the front on his own for 40 km (24.9 mi) before being caught with 5 km (3.1 mi) to go and finishing ninth. In the Roubaix Velodrome, Simpson rode a lap of honour after the race at the request of the emotional crowd. His televised effort launched his career, and he was now known throughout Europe.[76][77][74] Simpson won the Mont Faron hill climb and finished sixth in the five-day Genoa-Rome race, winning King of the Mountains.[66][78] He rode the Ardennes classics, placing seventh in La Flèche Wallonne and eleventh in Liège–Bastogne–Liège.[79] In May he won the general classification of the Tour du Sud-Est, his first overall victory in a professional stage race.[80][81]

In June, Simpson made his Grand Tour debut at the Tour de France at age 22. Rapha team manager Raymond Louviot opposed his participation, but since the race was contested by national teams Simpson accepted the invitation from the British squad.[82] During the first stage, he was part of a 13-rider breakaway which finished over two minutes in front of the field; he finished 13th after crashing on the cinder track at the finish in Brussels, but received the same time as the winner.[82][83] Later that day he finished ninth in the time trial, covering 27.8 km (17.3 mi) one minute 23 seconds slower than the winner (Roger Rivière of France) and moving up to fifth place overall.[83][84] During the third stage Simpson was part of a breakaway with two French riders who repeatedly attacked, forcing him to chase and use energy needed for the finish; he finished third, missing the 30-second bonus for a first-place finish (which would have put him in the yellow jersey).[85][82] He dropped to ninth overall by the end of the first week.[84] During stage ten, Simpson crashed descending the Col d'Aubisque in the Pyrenees but finished the stage in 14th place.[86][82] In the following stage (from Pau to Luchon) he was dropped, exhausted, from a chasing group; failing to recover, he finished in 29th place overall.[82][84] Simpson lost 2 st (13 kg; 28 lb) in weight over the three-week race.[87]

After the Tour, Simpson rode criteriums around Europe until crashing in central France; he returned home to Paris and checked himself into a hospital.[88][89] Following a week's bedrest, he rode in the road world championships at the Sachsenring in East Germany. During the race Simpson stopped to adjust his shoes on the right side of the road and was hit from behind by a car, sustaining a cut to his head which required five stitches.[90] He struggled in the last of the classics,[91] finishing 84th in the Giro di Lombardia.[92]

1961: Tour of Flanders and injury

Simpson's first major event of the 1961 season was the Paris–Nice stage race in March. During stage three his team won the team time trial, giving him the leader's jersey and the GC lead by three seconds; however, he lost it in the next stage. In the final stages of the race Simpson's attacks were thwarted, and he finished fifth overall. In his next race (Milan – San Remo), teammate Jean-Claude Annaert was part of a breakaway. Simpson helped prevent other riders from bridging the gap and finished 25th. The next day, he rode the opening stage of the short Menton–Rome race. Simpson placed second in two stages, finishing second overall to teammate Albertus Geldermans.[93]

On 26 March, Simpson rode the Tour of Flanders. With Carpano's Nino Defilippis, he chased down an early break that included 1959 winner (and world champion) Rik Van Looy of Wiel's-Flandria and Simpson's teammate Jo de Haan. Simpson worked with the group; with about 8 km (5.0 mi) to go he attacked, followed by Defilippis. The finish, three circuits around the town of Wetteren, was flat; Defilippis (unlike Simpson) was a sprinter and was expected to win. One kilometre from the finish, Simpson launched a sprint; he eased off with 300 m to go, tricking Defilippis into thinking he was exhausted. As Defilippis passed on his right, Simpson jumped again; Defilippis looked left to see Simpson lunge ahead, becoming the first Briton to win a "monument" classic.[94][74][95] Defilippis protested that the finishing banner had been blown down, and he did not know where the finish was; however, the judges noted that the finish line was clearly marked on the road itself.[96]

A week later, Simpson rode in Paris–Roubaix in the hope of bettering his previous year's ninth place. As the race reached the paved section, he went on a solo attack and was told that Mercier-BP-Hutchinson rider Raymond Poulidor was chasing him down. Simpson increased his speed, catching the vehicles in front. A press car swerved to avoid a pothole; this forced him into a roadside ditch. Simpson fell, damaging his front wheel and injuring his knee. He found his team car and retrieved a replacement wheel, but by then the front of the race had passed. Back in the race he crashed twice more, finishing 88th (about 30 minutes behind winner Van Looy).[74][97][92]

At Simpson's next race, the G.P. Eibar, his knee injury still bothered him. He won the second stage, but was forced to quit during the following stage. His injury had not healed; after seeing several specialists, for financial reasons he rode the Tour de France with the British team.[98] Simpson abandoned on stage three because pedaling was a struggle.[98][99] Three months after his fall at Paris–Roubaix he saw a doctor at St. Michael's Hospital in Paris, who diagnosed the problem as arthritis. He gave Simpson 16 knee injections, which reduced the inflammation. Once healed, he competed in the world championships in Berne, Switzerland. On the track he qualified for the individual pursuit with the fourth-fastest time, losing in the quarterfinals to Peter Post of the Netherlands. In the road race, Simpson was part of a 17-rider break that finished together in a sprint; he crossed the line in ninth place.[100]

1962: Yellow jersey

Simpson moved to Ghent, Belgium, and was earning money in one-day races around the country.[101] His contract with Rapha-Gitane-Dunlop had ended with the 1961 season. Tour de France winner Jacques Anquetil signed with them for 1962, but Simpson wanted to lead a team and signed with Gitane-Leroux-Dunlop (a new team for the 1962 season).[102][101] After training camp at Lodeve in southern France, he rode in Paris–Nice.[103] Simpson helped his team win the stage-three team time trial and finished second overall, behind Flandria-Faema-Clément's Jef Planckaert.[103][104][105][106] He was unable to ride Milan – San Remo when its organisers limited the race to Italian-based teams;[n 1] instead he rode in Gent–Wevelgem, finishing sixth,[103] and defended his Tour of Flanders title. As the race ended, Simpson was in a select group of riders at the front. Although he led over each of the final climbs, at the finish he finished fifth behind Van Looy and won the King of the Mountains prize.[108] A week later Simpson finished 37th in Paris–Roubaix, delayed by a crash.[109][105] In May he crashed during the opening stage of the Four Days of Dunkirk, losing over six minutes; although this removed him from contention for overall victory he finished 20th, using the race for training. Simpson's next races were the Tour de Luxembourg and the Manx Trophy.[110]

.svg.png)

Coming into the Tour de France, Simpson was leader of the Gitane-Leroux-Dunlop team;[111] it was the first time since 1929 that company teams were allowed to compete.[112] He finished ninth in the first stage (from Nancy to Spa),[111] in a group of 22 riders who finished over eight minutes ahead of the rest.[105] Simpson's team finished second to Flandria-Faema-Clément in the stage-2b team time trial; he was in seventh place overall,[113] remaining in the top ten the rest of the first week.[113] During stage 8a he was in a 30-rider group which gained about six minutes, moving him to second overall behind teammate Darrigade.[114] In the stage's second half (a time trial) Simpson finished 18th when a late starting position left him exposed to poor conditions, although he retained his overall position.[115] Stage 12 from Pau to Saint-Gaudens, the hardest stage in the Pyrenees and known as the "circle of death", was the Tour's first mountain stage.[112][116] Simpson saw an opportunity to wear the yellow jersey, since Darrigade was a poorer climber.[105][117] As the peloton reached the 2,115 m (6,939 ft)-high Col du Tourmalet, Simpson attacked with a small group of select riders and reached the summit in ninth place. A group of three broke away over the next two climbs, but were caught at the finish. Simpson finished the stage in 18th place, 30 seconds ahead of Geldermans (St. Raphaël-Helyett-Hutchinson) on GC and the first British rider to wear the leader's yellow jersey (a feat unmatched for 32 years, until Chris Boardman won the prologue of the 1994 Tour).[105][118][119][106]

Simpson lost the lead on the following stage, an 18.5 km (11.5 mi) time trial ending with a steep uphill finish at Superbagnères. He finished 31st, five minutes and 40 seconds behind winner Federico Bahamontes of Margnat-Paloma-D'Alessandro and dropped to sixth overall.[112][106][113] In the first Alpine stage (stage 18 from Juan-les-Pins to Briançon, the highest town in Europe) Simpson finished ninth and moved up to third overall, behind Planckaert and Anquetil.[105][113] He advanced recklessly descending the Col de Porte in the next stage, crashing on a bend and only saved from falling over the edge by a tree. Simpson finished the stage in 32nd place, slipping back to third, and the crash left him with a broken left middle finger. He lost almost 11 minutes to winner of the next stage's time trial (and eventual overall winner) Anquetil, finishing the Tour at Paris' Parc des Princes 17 minutes and nine seconds behind in sixth place.[120][105] He rode criteriums before the road world championships in Salò, Italy, where he retired with 25 mi (40.2 km) to go after missing a large breakaway.[105] He began six-day racing into his winter break, training in Ghent; in early October he finished third in the Six Days of Madrid with his partner, Australian John Tresidder.[105][121]

1963: Bordeaux–Paris

Leroux withdrew its sponsorship of the Gitane team for the 1963 season. Simpson was contracted to their manager, Raymond Louviot; Louviot was rejoining St. Raphaël-Gitane-Geminiani and Simpson could follow, but he saw that as a step backwards. Peugeot-BP-Englebert bought the contract (which ran until the end of the season) from Louviot.[122] Simpson's season opened with Paris–Nice; he fell out of contention after a series of punctures in the opening stages, and withdrew from the race on the final stage. After breaking away by himself he stopped beside the road, which annoyed his fellow riders.[123] At Milan – San Remo, Simpson was in a four-rider break that gained about three minutes; his tyre then punctured, and although he got back to the front, he finished 19th.[124][125] In late March he rode in Gent–Wevelgem, finishing second to Wiel's-Groene Leeuw rider Benoni Beheyt by one centimetre. The three-day Tour de Var followed; Simpson won the first stage in an uphill sprint, and finished second overall.[126][127] He placed third in the Tour of Flanders in a three-rider sprint.[128] In Paris–Roubaix Simpson worked for teammate (and winner) Emile Daems, finishing ninth. In the one-day Paris–Brussels he was in a breakaway near the Belgian border; with 50 km (31.1 mi) remaining he was left with world champion Jean Stablinski (St. Raphaël-Gitane-Geminiani), who attacked on a cobbled climb in Alsemberg outside Brussels. Simpson's bike slipped a gear, and Stablinski stayed away for the victory. After his second-place finish, Simpson led the Super Prestige Pernod International season-long competition for world's best cyclist. The following week he raced the Ardennes classics, placing seventh in la Flèche Wallonne and 33rd in Liège–Bastogne–Liège; in the latter, he rode alone for about 100 km (62.1 mi) before being caught in the final 5 km (3.1 mi).[129][127]

On 26 May, Simpson rode the one-day, 557 km (346 mi) Bordeaux–Paris. Also known as the Derby of the Road, it was the longest he had ever ridden.[130][131] The race began at 1:58 am; the initial 161 km (100 mi) were unpaced until the town of Châtellerault, where derny bikes paced each rider to the finish. Simpson broke away with a group of three riders including 1962 winner Jo de Roo (St. Raphaël-Gitane-Geminiani) and Peter Post (Dr. Mann-Labo). Simpson's pacer, Fernand Wambst, increased his speed, and Simpson dropped the other two. He caught the lead group, 13 minutes ahead, over a distance of 161 km (100 mi). Simpson attacked, and with 36 km (22 mi) remaining opened a margin of two minutes. His lead steadily increased, and he finished in the Parc des Princes over five minutes ahead of teammate Piet Rentmeester.[105][132][133][127]

Simpson announced that he would not ride the Tour de France, concentrating on the world road championships instead. He won the Manx Trophy, a one-day race on the Isle of Man, in treacherous conditions where only 16 out of 70 riders finished. At the road world championships in Ronse, Belgium, Simpson was favoured with Van Looy (although Simpson had only three teammates, compared to Van Looy's ten). The Belgians controlled the race until Simpson broke free, catching two riders ahead: Henry Anglade (France) and Seamus Elliott (Ireland). Anglade was dropped, and Elliott refused to work with Simpson.[n 2] They were caught; the race finished in a bunch sprint,[135] with Simpson crossing the line in fourth.[136]

Simpson placed second at the Critérium des As in Paris to Anquetil, and in Paris–Tours to Jo de Roo (St. Raphaël-Gitane-Geminiani). He was tenth in the Giro di Lombardia, finishing the Super Prestige Pernod International in second place behind Anquetil. Simpson's season ended with six-day races in Madrid, Brussels and Ghent before an invitation to race on the Pacific island of New Caledonia with riders who included Anquetil and De Roo.[137][127]

1964: Milan – San Remo

After a training camp near Nice in southern France Simpson rode the one-day Kuurne–Brussels–Kuurne in Belgium, finishing second to Solo-Superia's Arthur Decabooter in cold conditions.[138][139][140] In Paris–Nice his tyre punctured during stage four, losing five minutes and using the rest of the race for training.[141] Two days later, on 19 March, he rode in Milan – San Remo.[141][142] Before the race, French journalist René de Latour advised Simpson not to attack early: "If you feel good then keep it for the last hour of the race."[141] In the final 32 km (19.9 mi), a group of four riders (Simpson. 1961 winner Poulidor of Mercier-BP-Hutchinson, Flandria-Romeo's Willy Bocklant and Vincenzo Meco of Cite) broke away. At the foot of the Poggio (the final climb), Poulidor attacked and only Simpson stayed with him. Poulidor launched a series of attacks on Simpson; all failed as they crossed the summit and descended into Milan, 3 km (1.9 mi) away. With 500 m to go, Simpson began his sprint; Poulidor could not respond, leaving him to take the victory with a record average speed of 27.1 mph (43.6 km/h).[142][143][144][140][145] In the five-day Circuit de Provençal, Simpson recovered from an intestinal problem to win the fifth stage.[146] The following week, he rode in Paris–Roubaix. A strong tailwind split the race, and Simpson was in the front group. He crashed twice and failed to catch the leaders, finishing tenth.[147][148]

Simpson spent the next two months training for the Tour de France, finishing eighth in the Manx Trophy.[149] After the first week of the Tour, Simpson was in tenth place overall.[150] During the ninth stage (from Briançon to Monaco), he attacked on the final climb; a group of 22 riders (including Simpson) finished on a cinder track. Simpson was second behind Anquetil, moving up to eighth overall.[151][152] The next day, he finished 20th in the 20.8 km (12.9 mi) time trial.[150] During the 16th stage (which crossed four cols) Simpson finished 33rd, 25 minutes ten seconds behind the stage winner Federico Bahamontes, and dropped to 17th overall.[153][154] He finished the Tour in 14th place overall, 41 minutes and 50 seconds behind winner Jacques Anquetil.[150] Simpson later discovered that he rode the Tour with tapeworms.[153][155]

After the race, Simpson prepared for the world road championships with distance training and criteriums.[156] At the world championships on 3 September, the 290 km (180.2 mi) road race consisted of 24 laps of a varying circuit at Sallanches in the French Alps.[157][158][143] He crashed on the third lap while descending in wet conditions, damaging a pedal. Simpson got back to the peloton, launching a solo attack on a descent; he then chased down the group of four leaders with 42 mi (67.6 km) – two laps – to go. On the last lap he was dropped by three riders, finishing six seconds behind.[159][160][143] On 17 October, Simpson rode in the Giro di Lombardia. Halfway through the race he was given the wrong musette by his team in the feed zone, and threw it away. With the race reduced to five riders, Molteni's Gianni Motta attacked. Simpson was the only one who could follow, but he began to feel the effects of not eating. Motta gave him part of his food, which sustained him for a while. On the final climb Simpson led Motta, but was exhausted. Over the remaining 10 km (6.2 mi) of flat terrain, Motta dropped him; he was repeatedly overtaken,[161][162][140][143] finishing 21st.[92] Simpson's effort in the race earned a place in the two-man team time trial, the Trofeo Baracchi, with Rudi Altig of St. Raphaël-Gitane-Dunlop. Although he was still recovering from the Giro di Lombardia, they finished third. He closed the year on the track, riding six-day races and a derny-paced madison.[163][140][143]

1965: World championship and Lombardia

During the winter Simpson injured himself skiing in Saint-Gervais-les-Bains, suffering a broken foot and a sprained ankle. He recovered to ride in the lucrative Milan six-day race. Simpson followed it with the Antwerp six-day, dropping out on the fourth day with a cold. His cold worsened and he missed most of March, abandoning Milan – San Remo and Gent–Wevelgem. He began to recover later in the month, finishing fifth in Harelbeke–Antwerp–Harelbeke, sixth in the Circuit of the Eleven Towns and third overall in the Circuit de Provençal.[164][165] On 11 April, he finished seventh in Paris–Roubaix after crashing in the lead group.[166][167] The crash forced him to miss the Tour of Flanders as he struggled to walk on his injured foot. In la Flèche Wallonne he broke away with two other riders but was outsprinted, finishing third and claiming the King of the Mountains title.[168] In Liège–Bastogne–Liège he attacked with Salvarani's Felice Gimondi, catching an early break with 50 km (31.1 mi) remaining. They worked together for 25 km (15.5 mi), until Gimondi gave up. Simpson rode alone before slipping on oil mixed with water; he stayed with the front group, finishing tenth.[169][170]

Simpson rode the 265 mi (426.5 km) London–Holyhead race, winning in a bunch sprint and setting a record of ten hours 29 minutes.[143][171] He followed with an appearance at Bordeaux–Paris. François Mahé (Pelforth-Sauvage-Lejeune) went on a lone break; Simpson attacked in pursuit of Mahé, followed by Jean Stablinski. Simpson's derny broke down, and he was delayed changing motorbikes. He caught Stablinski, and was joined by Anquetil. Outside Paris Mahé was caught and dropped, after 200 km (124.3 mi) on his own. Anquetil won the race by 57 seconds over Stablinski, who beat Simpson in a sprint.[170][172][173] Peugeot-BP-Englebert manager Gaston Plaud ordered Simpson to ride the Midi Libre stage race to earn a place in the Tour de France, and he finished third overall.[174][175] The 1965 Tour was considered open due to Anquetil's absence, and Simpson was among the riders favoured by French newspaper L'Équipe. In the stage-1b team time trial, his team finished second to Ford-France-Gitane. During stage nine he injured his hand crashing on the descent of the Col d'Aubisque in the Pyrenees, finishing tenth in the stage and seventh in GC. Sinpson developed bronchitis after stage 15 and cracked on the next stage (from Gap to Briançon), losing nearly 19 minutes. His hand became infected, but he rode the next three stages before the Tour doctor stopped him from racing.[170][176][177] He was taken to hospital and treated for blood poisoning and a kidney infection.[87][178]

After ten days off his bike, Simpson rode three contracted post-Tour criteriums (which were all he was offered). His training for the road world championships included kermesse races. Simpson's last race before the world championships was the Paris–Luxembourg stage race, riding as a super-domestique.[179] On 5 September, Simpson rode in the road race at the world championships in San Sebastián, Spain.[180] The race was a 267.4 km (166.2 mi) hilly circuit of 14 laps. The British team had no support; Simpson and his friend Albert Beurick supplied food and drink, stealing from other teams.[181][182] During the first lap, a strong break was begun by British rider Barry Hoban. As his lead stretched to one minute Simpson and teammates Vin Denson and Alan Ramsbottom bridged the gap, followed by Germany's Rudi Altig. Hoban kept the pace high enough to prevent any of the favourites from joining. Simpson and Altig broke clear over Hernani Hill, with two-and-a-half laps remaining. They stayed together until the final kilometre, when Simpson launched his sprint; he held off Altig for victory by three bike lengths, becoming the first British world road race champion.[183][184] Simpson would be the only British world road race champion for 46 years, until Mark Cavendish won in 2011.[5]

Simpson's next major race was Paris–Tours; he had two lone breaks, but was caught by the peloton with over 2 mi (3.2 km) to go.[185] On 16 October Simpson rode the Giro di Lombardia, which featured five mountain passes. He escaped with Motta, and dropped him 6 mi (9.7 km) before the finish in Como to win his third "monument" classic three minutes 11 seconds ahead of the rest. Simpson was the second world champion to win in Italy; the first was Alfredo Binda in 1927.[186][187][188] He was offered lucrative contracts by Italian teams, but was signed with Peugeot-BP-Michelin until the end of the 1967 season. For the next three weeks he rode contract races, partnering with Post for victory in the six-day race at Brussels. He ended the year second to Anquetil in Super Prestige Pernod International, winning the Daily Express Sportsman of the Year, the Sports Journalists' Association Sportsman of the Year and the BBC Sports Personality of the Year (with Formula One world champion Jim Clark finishing second).[189][190][191] In British cycling Simpson won the Bidlake Memorial Prize in 1965,[192] and in Ghent he was given the freedom of Sint-Amandsberg (a sub-municipality in Ghent).[193]

1966: An injury ridden season

As he did the previous winter, Simpson went on a skiing holiday. On 25 January he fell, breaking his right tibia, and his leg was in a plaster cast until the end of February. He missed contract races, crucial training and most of the spring classics. Simpson began riding in March; within two weeks he rode his first road race (a criterium in Sint-Niklaas, Belgium), followed by an omnium track event in Antwerp. He rode a derny-paced race at the Good Friday Meeting at Herne Hill, defeating other British pros. In late April he started (but did not finish) Liège–Bastogne–Liège, and in early May he finished 20th in the Four Days of Dunkirk.[194]

Simpson's injury did not stop the press from naming him a favourite for the Tour de France.[194] He was quiet in the race until stage 12, when he forced a breakaway with Altig (Molteni-Hutchinson) and finished second to the German.[195][196] Simpson again finished second in the next stage, jumping clear of the peloton with Molteni-Hutchinson's Georges Vandenberghe and Smith's Guido De Rosso with 7 km (4.3 mi) to go. After the stage he was 18th overall, seven minutes 35 seconds down.[197][196] Simpson moved up to 16th after finishing fifth in stage 14b – a 20 km (12.4 mi) time trial – 20 seconds behind the winner, Poulidor (Mercier-BP-Hutchinson).[195][196] As the race reached the Alps, Simpson decided to make his move. During stage 16 (from Le Bourg-d'Oisans to Briançon) Simpson attacked on the descent of the first of three mountains, the Col de la Croix de Fer. He crashed but continued, attacking again. Simpson was joined by Ford France-Hutchinson's Julio Jiménez on the climb of the Col du Télégraphe to the Col du Galibier. Simpson was caught by a chase group descending the Galibier before he crashed again, knocked off his bike by a press motorcycle. The crash required five stitches in his arm.[198][112][196][199] The next day he struggled to hold the handlebars and could not use the brake lever with his injured arm, forcing him to abandon. His answer to journalists asking about his future was, "I don't know. I'm heartbroken. My season is ruined."[200]

After recovering from his injury Simpson rode 40 criteriums in 40 days, capitalising on his world championship and his attacks in the Tour.[201] He retired from the road world championships,[188] and his road season ended with retirements from autumn classics Paris–Tours and the Giro di Lombardia. He rode six-day races, finishing 14th in the winter rankings.[202] The misfortune he endured during the year made him one of the first riders named as a victim of the "curse of the rainbow jersey".[203]

1967: Paris–Nice and Vuelta stages

Simpson's primary objective for 1967 was overall victory in the Tour de France; in preparation, he planned to ride stage races instead of one-day classics. Simpson felt his chances were good because this Tour was contested by national (rather than corporate) teams.[199][204][n 3] He would lead the British team, which – although one of the weakest – would support him totally (unlike his corporate team, Peugeot-BP-Michelin).[199][206][207][208] During Simpson's previous three years with Peugeot, he was guaranteed a place on their Tour team if he signed with them for the following year.[204][209] Free to join a new team for the 1968 season, he was offered at least ten contracts; Simpson had a verbal agreement with Italian team Salvarani, and would share its leadership with Felice Gimondi.[210][204][211] He planned to attempt the one-hour record after the Tour.[49][204]

Simpson's first victory of the season was in the Giro di Sardegna in late February, where he also took the fifth stage.[212][213] On 8 March he started his next race, Paris–Nice.[204] After stage two his 23-year-old teammate, Eddy Merckx, took the overall lead.[204][214] Simpson moved into the lead the next day as part of a breakaway (missed by Merckx) which finished nearly 20 minutes ahead. Merckx thought Simpson double-crossed him, but Simpson was a passive member of the break.[188][215] At the start of stage six, Simpson was in second place behind Rolf Wolfshohl of Bic. Merckx drew clear as the race approached Mont Faron, with Simpson following. They stayed together until the finish in Hyères, with Merckx placing first. Simpson finished one minute 26 seconds ahead of Wolfshohl, putting him in the leader's white jersey.[216] He held the lead in the next stage, finishing second in the final stage's time trial to win the race.[209] Simpson and Merckx's form continued into Milan – San Remo, which saw them in a six-rider breakaway lasting about 200 km (124.3 mi) before Merckx won in a bunch sprint.[217] After 110 mi (177.0 km) of Paris–Roubaix, Simpson's bike was unridable and he retired from the race.[188]

In late April Simpson rode for Great Britain in his first Vuelta a España, using the race to prepare for the Tour. During stage two a breakaway gained over 13 minutes, dashing his hopes for a high placing. Simpson nearly quit the race before the fifth stage (from Salamanca to Madrid), but rode it because it was easier to get home by air from Madrid. He won the stage, attacking from a breakaway, and finished second in stage seven. Simpson won stage 16 (from Vitoria to San Sebastian, where he became world champion), his second stage victory, and finished the Vuelta 33rd overall.[218][219]

Simpson was determined to make an impact in the Tour de France; in his eighth year as a professional cyclist, he hoped for larger appearance fees in post-Tour criteriums to help secure his financial future after retirement.[220][221][222] His plan was to finish in the top three or wear the yellow jersey, targeting three key stages (one of which was the 13th, over Mont Ventoux) and riding conservatively until the race reached the mountains.[223][224][225][226] In the prologue, Simpson finished 13th.[188] After the first week he was in sixth place overall, leading the favourites.[188][227][228] As the race crossed the Alps, Simpson fell ill during stage ten (across the Col du Galibier) with diarrhoea and stomach pains. Unable to eat, he finished the stage in 16th place and dropped to seventh overall as his rivals passed him.[228][229] The evening before stage 12 Simpson's manager, Daniel Dousset, pressured him for good results.[230][231][232] Teammate Vin Denson advised Simpson to limit his losses and accept what he had.[233] Peugeot manager Gaston Plaud, in Marseille, begged Simpson to quit the race.[234][208]

Death

The 13th stage (13 July) of the 1967 Tour de France measured 211.5 km (131.4 mi); it started in Marseille, crossing 1,910 m (6,270 ft)-high Mont Ventoux (the "Giant of Provence") before finishing in Carpentras.[227][235] As the race reached the lower slopes of Ventoux, Simpson (still ill) was seen washing pills down with brandy.[236][237][n 4] As the race neared the summit of Ventoux, the peloton began to fracture. Simpson was in the front group before slipping back to a group of chasers about a minute behind. He then began losing control of his bike, zig-zagging across the road.[242][n 5] A kilometre from the summit, Simpson fell off his bike. Team manager Alec Taylor and mechanic Harry Hall arrived in the team car to help him. Hall tried to persuade Simpson to stop ("Come on Tom, that's it, that's your Tour finished"), but Simpson said he wanted to continue. Taylor said, "If Tom wants to go on, he goes". Noticing his toe straps were still undone, Simpson said, "Me straps, Harry, me straps!" They got him on his bike and pushed him off.[243] Simpson's last words, as remembered by Hall, were "On, on, on." "Put me back on my bike!" was invented by Sid Saltmarsh, who was covering the Tour for The Sun and Cycling (now Cycling Weekly). Saltmarsh was not there at the time, and was in a dead reception zone for live accounts on Radio Tour.[243][244][245] Simpson rode a further 500 yards (460 m) before he began to wobble, and was held upright by three spectators; he was unconscious, with his hands locked on the handlebars. Hall and a nurse from the Tour's medical team took turns giving Simpson mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, before Tour physician Pierre Dumas arrived with an oxygen mask.[246][247][248] About 40 minutes after his collapse, a police helicopter took Simpson to a hospital in nearby Avignon,[247][249][208][250] where he was pronounced dead at 5:40 p.m.[247][208] Two empty tubes and a half-full one of amphetamines (one of which was labelled "Tonedron") were found in the rear pocket of his jersey.[251]

On the next racing day, the other riders were reluctant to continue racing and asked the organisers for a postponement.[252] France's Stablinski suggested that the race continue, with a British rider (whose team would wear black armbands) allowed to win the stage. The task fell to Barry Hoban, although many thought the stage winner should have been Denson (Simpson's close friend).[253][254][255][227] Although there was no inquest in Britain or France, on 31 July 1967 British journalist J. L. Manning of the Daily Mail broke the news about a formal connection between drugs and Simpson's death.[256] French authorities confirmed that Simpson had traces of amphetamine in his body, impairing his judgement and allowing him to push himself beyond his limits.[245][257] The official cause of death was heart failure due to dehydration and heat exhaustion, with drugs a contributing factor.[258] His death contributed to the introduction of mandatory testing for performance-enhancing drugs in cycling.[259][260] Simpson was buried in Harworth, after a service at the 12th-century village church attended by an estimated 5,000 mourners.[261][244]

Doping

Two years before his death, Simpson hinted in the British newspaper The People at drug-taking in races, although he implied that other competitors were involved.[262][263] Asked about drugs by Eamonn Andrews on the BBC Home Service radio network, Simpson did not deny taking them; however, he said that a rider who frequently took drugs might get to the top but would not stay there.[264]

William Fotheringham spoke to British professional cyclist Alan Ramsbottom for his biography of Simpson, Put Me Back on My Bike. He quoted Ramsbottom as saying, "Tom went on the [1967] Tour de France with one suitcase for his kit and another with his stuff, drugs and recovery things", which Fotheringham said was confirmed by Simpson's roommate Colin Lewis. Ramsbottom added, "Tom took a lot of chances. He took a lot of it [drugs]. I remember him taking a course of strychnine to build up to some big event. He showed me the box, and had to take one every few days."[265][n 6]

Riding style and legacy

Simpson looked for any advantage over his opponents. He made his own saddle, a design which is now standard. During his time with Peugeot, he rode bikes made by Italian manufacturer Masi that resembled Peugeots.[267] Simpson was obsessed with dieting since 1956, when he was mentored by Cyril Cartwright. Simpson understood the value of fruit and vegetables after reading Les Cures de jus by nutritionist Raymond Dextreit; during the winter, he would consume 10 lb (4.5 kg) of carrots a day. Other unusual food preferences included pigeons, duck and trout skin, raspberry leaves and garlic in large quantities.[268]

A granite memorial to Simpson (with the words "Olympic medallist, world champion, British sporting ambassador") stands on the spot where he collapsed and died on Ventoux, one kilometre east of the summit.[269][270] Cycling began a fund for a monument the week after his death, raising about £1,500. The memorial was unveiled in 1968 by Simpson's widow Helen, Barry Hoban and British team manager Alec Taylor. It has become a site of pilgrimage for cyclists, who frequently leave cycling-related objects (such as water bottles and caps) in tribute.[271][272] In nearby Bédoin, a plaque was installed in the town square by journalists following the 1967 Tour.[273] The Harworth and Bircotes Sports and Social Club has a museum dedicated to Simpson which was opened by Vin Denson, Barry Hoban, Arthur Metcalfe and Lucien Van Impe on 12 August 2001.[274] The main display includes the bicycle on which he won Paris–Nice in 1967 and the jersey, gloves and shorts he wore the day he died.[275][276] A replica of the Ventoux memorial was erected outside the club in 1997 to commemorate the 30th anniversary of his death.[276] In his adopted hometown of Ghent, there is a bust of Simpson in the Sportpalis (Sport Palace).[277] Every year since his death, the Tom Simpson Memorial Race has taken place in Harworth.[278][279]

Ray Pascoe, a fan, made the 1995 film Something To Aim At over a 30-year period; the film includes interviews with those closest to Simpson.[280] The 2005 documentary Wheels Within Wheels follows actor Simon Dutton as he searches for people and places in Simpson's life. Dutton's four-year project chronicles the midlife crisis that sparked his quest to rediscover Simpson.[281] British rider David Millar won stage 12 of the 2012 Tour de France on the 45th anniversary of Simpson's death; previously banned from cycling for using performance-enhancing drugs, he paid tribute to Simpson and reinforced the importance of learning from his – and Simpson's – mistakes.[155] Simpson inspired Simpson Magazine, which began in March 2013. According to the magazine's creators, “It was Simpson's spirit and style, his legendary tenacity and his ability to suffer that endeared him to cycling fans everywhere as much as the trophies he won”.[282]

Personal life

Soon after moving to France in 1959 the 21-year-old Simpson met 19-year-old Helen Sherburn, an au pair from Sutton, Yorkshire.[283] They married on 1 January 1961 and had two daughters, Jane and Joanne.[82][155] After his death, Helen Simpson married Barry Hoban in December 1969.[284] Simpson is the maternal uncle of Belgian cyclist Matthew Gilmore.[34]

He was interested in vintage cars, and his driving and riding styles were similar; Helen remembered, "Driving through the West End of London at 60 mph (97 km/h), was nothing."[285] On 31 January 1966, Simpson was a guest "castaway" on BBC Radio 4's Desert Island Discs; his favourite musical piece was "Ari's Theme" from Exodus by the London Festival Orchestra, his book choice was The Pickwick Papers and his luxury item was golf equipment.[286] Helen said that she chose his records for the show, since he was not interested in music.[287]

Career achievements

Major results

- 1955

- 1st

BLRC National Junior Hill Climb Championship

- 1956

- 3rd

Team pursuit, Olympic Games

Team pursuit, Olympic Games - 1957

- 1st

BLRC National Hill Climb Championship

- 1958

- 1st

Individual pursuit, Amateur National Track Championships

- 2nd

Individual pursuit, British Empire and Commonwealth Games

Individual pursuit, British Empire and Commonwealth Games - 1959

- Tour de l'Ouest

- 1st Stages 4 & 5b (ITT)

- 4th Road race, Road World Championships

- 1960

- 1st

Overall Tour du Sud-Est

Overall Tour du Sud-Est - 7th La Flèche Wallonne

- 9th Paris–Roubaix

- 1961

- 1st Tour of Flanders

- 1st Stage 2 Euskal Bizikleta

- 1st Stage 1b (TTT) Four Days of Dunkirk

- 5th Overall Paris–Nice

- 1st Stage 3 (TTT)

- 9th Road race, Road World Championships

- 1962

- 2nd Overall Paris–Nice

- 1st Stage 3a (TTT)

- 3rd Critérium des As

- 3rd Six Days of Madrid (with John Tresidder)

- 5th Tour of Flanders

- 6th Overall Tour de France

- 6th Gent–Wevelgem

- 1963

- 1st Bordeaux–Paris

- 1st Manx Trophy

- 2nd Critérium des As

- 2nd Gent–Wevelgem

- 2nd Paris–Brussels

- 2nd Overall Super Prestige Pernod International

- 2nd Paris–Tours

- 3rd Tour of Flanders

- 8th Paris–Roubaix

- 10th La Flèche Wallonne

- 10th Giro di Lombardia

- 1964

- 1st Milan – San Remo

- 2nd Kuurne–Brussels–Kuurne

- 3rd Trofeo Baracchi (with Rudi Altig)

- 4th Road race, Road World Championships

- 10th Paris–Roubaix

- 14th Overall Tour de France

- 1965

- 1st

Road race, Road World Championships

Road race, Road World Championships - 1st Giro di Lombardia

- 1st London–Holyhead

- 1st Six Days of Brussels (with Peter Post)

- 2nd Six Days of Ghent (with Peter Post)

- 2nd Overall Super Prestige Pernod International

- 3rd Overall Grand Prix du Midi Libre

- 3rd La Flèche Wallonne

- 3rd Bordeaux–Paris

- 5th Harelbeke–Antwerp–Harelbeke

- 6th Paris–Roubaix

- 10th Liège–Bastogne–Liège

- 1966

- 1st Stage 2b (TTT) Four Days of Dunkirk

- 2nd Six Days of Münster (with Klaus Bugdahl)

- 2nd Grosser Preis des Kantons Aargau

- 1967

- 1st

Overall Paris–Nice

Overall Paris–Nice - 1st Manx Trophy

- Vuelta a España

- 1st Stages 5 & 16

- 1st Stage 5 Giro di Sardegna

- 3rd Six Days of Antwerp (with Leo Proost and Emile Severeyns)

Grand Tour general classification results timeline

| Grand Tour | 1960 | 1961 | 1962 | 1963 | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | 1967 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 33 | |

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 29 | DNF | 6 | — | 14 | DNF | DNF | DNF |

| — | Did not compete |

| DNF | Did Not Finish |

Monuments results timeline

| Monument | 1959 | 1960 | 1961 | 1962 | 1963 | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | 1967 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milan – San Remo | — | 38 | 25 | — | 19 | 1 | DNF | — | 70 |

| Tour of Flanders | — | — | 1 | 5 | 3 | — | — | — | — |

| Paris–Roubaix | — | 9 | 88 | 37 | 8 | 10 | 6 | — | DNF |

| Liège–Bastogne–Liège | — | 11 | — | — | 33 | — | 10 | DNF | — |

| Giro di Lombardia | DNF | 84 | — | — | 10 | 21 | 1 | — | — |

| — | Did not compete |

| DNF | Did not finish |

Awards and honours

- BBC Sports Personality of the Year: 1965[191]

- Sports Journalists' Association Sportsman of the Year: 1965[190]

- Daily Express Sportsman of the Year: 1965[293]

- Bidlake Memorial Prize: 1965[192]

- British Cycling Federation Personality of the Year: 1965[193]

- British Cycling Hall of Fame: 2010[294]

See also

- List of British cyclists

- List of doping cases in cycling

- List of drug-related deaths

- List of Olympic medalists in cycling (men)

- List of professional cyclists who died during a race

Notes

- ↑ The organisers of the 1962 Milan – San Remo only allowed Italian teams to participate as an attempt to get an Italian winner, as the last one was in 1953.[103][107]

- ↑ Seamus Elliott rode for St. Raphaël-Gitane-Geminiani, the rival team of Simpson's Peugeot-BP-Englebert, and would not work with Simpson and risk him winning. Two years later it was revealed in The People that Simpson offered Elliott up to 15,000 francs (£1000) for him to work with him.[134]

- ↑ The national team format was used in the 1967 Tour de France after tour organiser, Félix Lévitan, believed the team sponsors were behind the riders strike in the previous year's Tour.[205]

- ↑ Alcohol was used as a stimulant and to dull pain.[238] At the time, the Tour de France organisers limited each rider to four bottles (bidons) of water (about two litres) two on the bike and two more given at feeding stations – the effects of dehydration being poorly understood. During races, riders raided roadside bars for drinks, and filled their bottles from fountains.[239][240][235][241]

- ↑ Zig-zagging on an ascent is way of lessening the gradient.

- ↑ Strychnine is one of the oldest drugs used in cycling. In small quantities it tightens the muscles.[266]

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Index entry". FreeBMD. Newport, UK: Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ↑ "Remembering Mr Tom". BBC Sport (London: BBC). 28 July 2002. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

Simpson, "Mr Tom" as he came to be known, was the first rider from the UK to make his mark in the tough world of professional European cycling.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Fotheringham 2007, p. 229.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Sidwells 2000, p. 15.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 MacLeary, John (26 September 2011). "Britain's world champions head-to-head: Mark Cavendish v Tom Simpson". The Daily Telegraph (London: Telegraph Media Group). Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Fotheringham 2007, p. 45.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 16.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 17.

- ↑ Pascoe 1997, 7 minutes in.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Sidwells 2000, p. 18.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Simpson 2009, pp. 9–11.

- ↑ Pascoe 1997, 9 minutes in.

- ↑ Simpson 2009, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 48.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 "Remembering Tom Simpson". Cycling (London): 20–21. 1 January 1977.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Sidwells 2000, p. 24.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Simpson 2009, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 29.

- ↑ Pascoe 1997, 11 minutes in.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 32–34.

- ↑ Simpson 2009, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 36.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Pascoe 1997, 17 minutes in.

- ↑ Simpson 2009, pp. 20–23.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 39–41.

- ↑ Simpson 2009, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Sidwells 2000, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Simpson 2009, pp. 25–35.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "Tom Simpson". Sports-Reference.com. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Simpson 2009, p. 38.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 52–54.

- ↑ Simpson 2009, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Hilton 2005, p. 367.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 55.

- ↑ Simpson 2009, pp. 40–43.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 56–59.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Simpson 2009, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Simpson 2009, pp. 44–47.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Simpson 2009, pp. 47–48.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Simpson, Tom (1 April 1967). 'I'll get the hour – before the others try' . Cycling. Interview with Ken Evans (London: Longacre Press): 4–5.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 64.

- ↑ Simpson 2009, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 65–66.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 64–67.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 69–74.

- ↑ Simpson 2009, pp. 64–67.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 62.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Fotheringham 2007, p. 61.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 74.

- ↑ Simpson 2009, p. 67.

- ↑ Simpson 2009, p. 70.

- ↑ "Tour de l'Ouest 1959". Cycling Archives. de Wielersite. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 77.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 78–81.

- ↑ Simpson 2009, pp. 73–75.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 "The first big wins". Cycling. Remembering Tom Simpson (London: IPC Media): 16–17. 8 January 1977.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 83.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 "Volatone a Milano e vittoria di Van Looy" [Volatone in Milan and win Van Looy] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). 19 October 1959. p. 6. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ↑ Mannini, Paul. "53a edizione Giro di Lombardia (1959)" [53rd Tour of Lombardy (1959)]. Museo del Ciclismo (in Italian). Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 83–84.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ "The 1960 Milan–San Remo". The Milan–San Remo Cycle Race. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ↑ "The 1960 Milan–San Remo result". The Milan–San Remo Cycle Race. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 74.3 Jones, Graham (April 2006). "The Flanders Lion Tamer". CyclingRevealed. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 99.

- ↑ Bouvet 2007, p. 103.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 88–91.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 251.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 91.

- ↑ "Tour du Sud-Est 1960". Cycling Archives. de Wielersite. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 92.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 82.3 82.4 82.5 "Tackling his first Tour". Cycling. Remembering Tom Simpson (London: IPC Media): 18–19. 15 January 1977.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Sidwells 2000, p. 94.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 84.2 "1960 Tour de France". BikeRaceInfo. Cherokee Village, AR: McGann Publishing. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 95–96.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 Fotheringham 2007, p. 190.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, pp. 129–130.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 98.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 100.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 92.2 92.3 92.4 "Tom Simpson (Great Britain)". The-Sports.org. Québec, Canada: Info Média Conseil. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 102–104.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 105–107.

- ↑ Lion, Jan (27 March 2011). "Tom Simpson won in 1961". Het Nieuwsblad (in Dutch) (Brussels: Corelio). Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 107.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 Sidwells 2000, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 65.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 111–113.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 Sidwells 2000, p. 114.

- ↑ Simpson 2009, p. 110.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 103.2 103.3 Sidwells 2000, p. 115.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 252.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 105.2 105.3 105.4 105.5 105.6 105.7 105.8 105.9 "The Yellow Jersey". Cycling. Remembering Tom Simpson (London: IPC Media): 22–23. 22 January 1977.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 106.2 "The starters". The history of the Tour de France. Issy-les-Moulineaux, France: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ↑ "Past winners". The Milan-San Remo Cycle Race. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 116–117.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 117.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 119–121.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 Sidwells 2000, p. 122.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 112.2 112.3 McGann & McGann 2006, p. 253.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 113.2 113.3 "1962 Tour de France". BikeRaceInfo. Cherokee Village, AR: McGann Publishing. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ "Stage 8.01 Saint-Nazaire > Luçon". The history of the Tour de France. Issy-les-Moulineaux, France: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 19 August 2010. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 123.

- ↑ McGann & McGann 2006, pp. 277–288.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 124.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 123–125.

- ↑ "Stage 12 Pau > Saint-Gaudens". The history of the Tour de France. Issy-les-Moulineaux, France: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 19 August 2010. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 126–128.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 134.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 137–138.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 138.

- ↑ "1963 Milano – San Remo". BikeRaceInfo. Cherokee Village, AR: McGann Publishing. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 139–141.

- ↑ 127.0 127.1 127.2 127.3 "The starters". The history of the Tour de France. Issy-les-Moulineaux, France: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ↑ "1963 Tour of Flanders". BikeRaceInfo. Cherokee Village, AR: McGann Publishing. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 139–144.

- ↑ "Bordeaux–Paris 1963". Cycling Archives. de Wielersite. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 145.

- ↑ Wadley, J. B. (July 1963). "Tea-Time at the Parc". Sporting Cyclist (Charlie Buchan). Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 147–149.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 154.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 150–151.

- ↑ "World Championships 1963". The-Sports.org. Québec, Canada: Info Média Conseil. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 156–159.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 162.

- ↑ "Kuurne–Brussels–Kuurne". BikeRaceInfo. Cherokee Village, AR: McGann Publishing. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ↑ 140.0 140.1 140.2 140.3 "The starters". The history of the Tour de France. Issy-les-Moulineaux, France: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ↑ 141.0 141.1 141.2 Sidwells 2000, p. 163.

- ↑ 142.0 142.1 "The 1964 Milan-San Remo". The Milan-San Remo Cycle Race. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ 143.0 143.1 143.2 143.3 143.4 143.5 "World Champion". Cycling. Remembering Tom Simpson (London: IPC Media): 8–9. 29 January 1977.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 163–164.

- ↑ Simpson, Tom (28 March 1964). "First '64 Classic goes to Simpson". Cycling and Mopeds (London: Longacre Press). Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 165–166.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 166–167.

- ↑ Jones, Graham (March 2008). "Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose" [The more things change, the more they stay the same]. CyclingRevealed. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 167–168.

- ↑ 150.0 150.1 150.2 "1964 Tour de France". BikeRaceInfo. Cherokee Village, AR: McGann Publishing. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 169.

- ↑ "1964 Tour de France". Cycling (London: Temple Press). July 1964. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ 153.0 153.1 Sidwells 2000, p. 171.

- ↑ "Stage 16 Luchon > Pau". The history of the Tour de France. Issy-les-Moulineaux, France: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 19 August 2010. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- ↑ 155.0 155.1 155.2 "Tom Simpson: Forgotten by all but one". The Scotsman (Edinburgh: Johnston Press). 18 July 2009. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 151.

- ↑ "World Professional (Elite) Road Cycling Championship". BikeRaceInfo. Cherokee Village, AR: McGann Publishing. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 173.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 172–175.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 136.

- ↑ "17 ottobre 1964 – Giro di Lombardia" [17 October 1964 – Tour of Lombardy]. Museo del Ciclismo (in Italian). Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 177.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 178–181.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 183–185.

- ↑ Simpson 2009, pp. 158–160.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 185–186.

- ↑ "Trionfo solitario di Rik Van Looy sul traguardo dell Parigi–Roubaix" [Rik Van Looy solitary triumph at the finish line of the Paris–Roubaix]. La Stampa (in Italian). 13 April 1965. p. 13. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 185.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 187–188.

- ↑ 170.0 170.1 170.2 "The starters". The history of the Tour de France. Issy-les-Moulineaux, France: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ↑ Simpson 2009, pp. 163–165.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 191–192.

- ↑ Jones, Graham (November 2010). "The Legend, the D.S., the Domestique and an Englishman". CyclingRevealed. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 193.

- ↑ Simpson 2009, p. 167.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 193–196.

- ↑ "1965 Tour de France". BikeRaceInfo. Cherokee Village, AR: McGann Publishing. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 196.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 197–198.

- ↑ "World Championship, Road, Profs 1965". Cycling Archives. de Wielersite. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ "Albert Beurick". The Daily Telegraph (London: Telegraph Media Group). 4 January 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 200–202.

- ↑ "Simpson Champion". Cycling (London: Go Magazine): 16–17. 11 September 1965. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 204.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 204–205.

- ↑ Simpson 2009, pp. 179–180.

- ↑ 188.0 188.1 188.2 188.3 188.4 188.5 "That last tragic day on Mont Ventoux". Cycling. Remembering Tom Simpson (London: IPC Media): 11–12. 5 February 1977.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 207–210.

- ↑ 190.0 190.1 "Past winners of the SJA British Sports Awards". Sports Journalists' Association. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ↑ 191.0 191.1 "Sports Personality of the Year". BBC Press Office. London: BBC. 3 July 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ↑ 192.0 192.1 "Recipients". The F. T. Bidlake Memorial Trust. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ↑ 193.0 193.1 Sidwells 2000, p. 208.

- ↑ 194.0 194.1 Sidwells 2000, pp. 211–216.

- ↑ 195.0 195.1 "1966 Tour de France". BikeRaceInfo. Cherokee Village, AR: McGann Publishing. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ 196.0 196.1 196.2 196.3 "The starters". The history of the Tour de France. Issy-les-Moulineaux, France: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 19 August 2010. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 220–221.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 222–225.

- ↑ 199.0 199.1 199.2 Simpson, Tom (8 April 1967). 'We can win the Tour' . Cycling. Interview with Ken Evans (London: Longacre Press): 14–15.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 175.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 226.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 227–228.

- ↑ Wilcockson 2009, p. 159.

- ↑ 204.0 204.1 204.2 204.3 204.4 204.5 Sidwells, Chris (March 2012). "Paris–Nice 1967 – Part 1". ChrisSidwells.com. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ McGann & McGann 2008, p. 24.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 238.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 28.

- ↑ 208.0 208.1 208.2 208.3 Gallagher, Brendan (13 July 2007). "Tom Simpson haunts Tour 40 years on". The Daily Telegraph (London: Telegraph Media Group). Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ↑ 209.0 209.1 Sidwells 2000, p. 176.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 228.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 130.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 230.

- ↑ 213.0 213.1 "Tom Simpson". Cycling Archives. de Wielersite. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells, Chris (March 2012). "Paris–Nice 1967 – Part 2". ChrisSidwells.com. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells, Chris (March 2012). "Paris–Nice 1967 – Part 3". ChrisSidwells.com. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells, Chris (March 2012). "Paris–Nice 1967 – Part 4". ChrisSidwells.com. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ Mannini, Paul. "58a edizione Milano-Sanremo (1967)" [58th Milano-Sanremo (1967)]. Museo del Ciclismo (in Italian). Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 233–234.

- ↑ "Año 1967" [Year 1967]. Vuelta a España (in Spanish). Madrid: Unipublic. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ Watts 2011, 2 minutes in.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 237–238.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 239.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Laurence 2005, 5 minutes in.

- ↑ McGann & McGann 2008, p. 27–28.

- ↑ 227.0 227.1 227.2 "1967 Tour de France". BikeRaceInfo. Cherokee Village, AR: McGann Publishing. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ↑ 228.0 228.1 Sidwells 2000, p. 244.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 19.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 131.

- ↑ 231.0 231.1 McGann & McGann 2008, p. 27.

- ↑ Woodland, Les (21 July 2007). "Simpson: martyr, example, warning". Cyclingnews.com (Bath, UK: Future plc). Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ↑ Laurence 2005, 8 minutes in.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, pp. 216–217.

- ↑ 235.0 235.1 Rosen 2008, p. 32.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Dimeo 2007, p. 61.

- ↑ McGann & McGann 2008, p. vi.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 179.

- ↑ Watts 2011, 4 minutes in.

- ↑ Woodland, Les (3 October 2007). "The chasse à la canette". Bath, UK: Cyclingnews.com. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ↑ McGann & McGann 2008, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ 243.0 243.1 Fotheringham 2007, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ 244.0 244.1 Woodland 2007, p. 334.

- ↑ 245.0 245.1 Rosen 2008, p. 33.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, pp. 35–37.

- ↑ 247.0 247.1 247.2 Sidwells 2000, p. 248.

- ↑ Thompson 2008, p. 102.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 186.

- ↑ Nicholson, Geoffrey (14 July 1967). "Simpson dies after collapse on Tour". The Guardian (London: Guardian Media Group). Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 167.

- ↑ Laurence 2005, 56 minutes in.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 6.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Rosen 2008, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Manning, J. L. (31 July 1967). "Simpson was killed by drugs". Daily Mail (London: Associated Newspapers).

- ↑ Houlihan 2002, p. 65.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 13.

- ↑ Van Vleet, Samantha (16 March 2012). "1967 Death of Cyclist Tommy Simpson Brought Drug Testing to Cycling". Yahoo! Sports. Sunnyvale, CA: Yahoo!. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- ↑ McGann & McGann 2008, p. 32.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 100.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 149.

- ↑ Woodland, Les (4 July 1987). "Death of a British Tommy". BBC. BBC Radio 4. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Woodland 1980, pp. 140–142.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Anti-Doping". World Anti-Doping Agency. June 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, pp. 77–79.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 208.

- ↑ Williams & Le Nevez 2007, p. 83.

- ↑ Dauncey & Hare 2003, p. 214.

- ↑ Moore, Richard (26 July 2009). "British riders remember Tommy Simpson – a hero to some, to others the villain of the Ventoux". theguardian.com (London: Guardian Media Group). Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Woodland 2007, p. 265.

- ↑ "Tom Simpson". Daily Peloton. 12 August 2002. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Williams, Richard (13 July 2007). "White flowers for a man in white who rode himself to destruction". theguardian.com (London: Guardian Media Group). Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ↑ 276.0 276.1 "Simpson Museum". International Cycle Sport. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 14.

- ↑ "Cyclists flock to Harworth for Tommy Simpson races". Worksop Guardian. Retrieved: Johnston Press. 23 July 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 1–4.

- ↑ "Wheels Within Wheels with Simon Dutton". The Saint News. 24 April 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ↑ MacMichael, Simon (27 February 2013). "New cycling magazine Simpson launches this week". road.cc (Bath, UK: Farrelly Atkinson). Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 69.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 85.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Plomley, Roy (host) (31 January 1966). "Castaway: Tommy Simpson". Desert Island Discs. BBC. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 79.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, pp. 249–256.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, pp. 229–231.

- ↑ "Tom Simpson". The history of the Tour de France. Issy-les-Moulineaux, France: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ 291.0 291.1 "Palmarès de Tom Simpson (Gbr)" [Awards of Tom Simpson (Gbr)]. Memoire du cyclisme (in French). Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ↑ Sidwells 2000, p. 216.

- ↑ Fotheringham 2007, p. 105.

- ↑ "British Cycling Hall of Fame – 2010 Inductees". British Cycling. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

References

- Bouvet, Philippe (2007). Parijs–Roubaix: De Hel van het noorden [Paris–Roubaix: The Hell of the North] (in Dutch). Tielt, Belgium: Lannoo Uitgeverij. ISBN 978-90-209-6533-9. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- Dauncey, Hugh; Hare, Geoff (2003). The Tour De France, 1903–2003: A Century of Sporting Structures, Meanings and Values. London: Frank Cass & Co. ISBN 978-0-203-50241-9. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- Dimeo, Paul (2007). A History of Drug Use in Sport: 1876–1976: Beyond Good and Evil. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-00370-1. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- Fotheringham, William (2007) [1st. pub. 2002]. Put Me Back on My Bike: In Search of Tom Simpson. London: Yellow Jersey Press. ISBN 978-0-224-08018-7. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- Hilton, Tim (2005) [1st. pub. 2004:HarperCollins]. One More Kilometre and We're in the Showers. London: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-00-653228-6. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- Houlihan, Barrie (2002). Dying to Win: Doping in Sport And the Development of Anti-doping Policy, Part 996 (2nd ed.). Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe. ISBN 978-92-871-4685-4. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Laurence, Alastair (Director) (2005). Death on the Mountain: The Story of Tom Simpson (Television production). London: BBC. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- McGann, Bill; McGann, Carol (2006). The Story of the Tour De France, Volume 1: 1903–1964. Indianapolis, IN: Dog Ear Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59858-180-5. Retrieved 31 May 2013.