Tiwanaku

| Tiwanaku | |

|---|---|

|

The "Gate of the Sun" | |

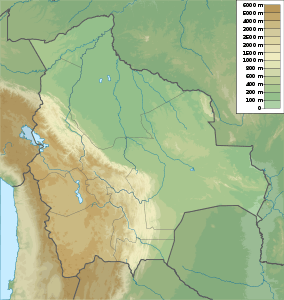

Shown within Bolivia | |

| Alternate name | Tiahuanaco, Tiahuanacu |

| Location | Tiwanaku Municipality, Bolivia |

| Coordinates | 16°33′17″S 68°40′24″W / 16.55472°S 68.67333°WCoordinates: 16°33′17″S 68°40′24″W / 16.55472°S 68.67333°W |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Cultures | Tiwanaku |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | In ruins |

| Official name | Tiwanaku: Spiritual and Political Centre of the Tiwanaku Culture |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv |

| Designated | 2000 (24th session) |

| Reference no. | 1269[1] |

| Region | Latin America and the Caribbean |

Tiwanaku (Spanish: Tiahuanaco or Tiahuanacu) is a Pre-Columbian archaeological site in western Bolivia, South America. It is the capital of an empire that extended into present-day Peru and Chile, flourishing from AD 300 to 1000.

Tiwanaku is recognized by Andean scholars as one of the most important civilizations prior to the Inca Empire; it was the ritual and administrative capital of a major state power for approximately five hundred years. The ruins of the ancient city state are near the south-eastern shore of Lake Titicaca in Tiwanaku Municipality, Ingavi Province, La Paz Department, about 72 km (45 mi) west of La Paz.

The site was first recorded in written history by Spanish conquistador Pedro Cieza de León. He came upon the remains of Tiwanaku in 1549 while searching for the Inca capital Qullasuyu.[2]

The name by which Tiwanaku was known to its inhabitants may have been lost as they had no written language.[3][4] The Puquina language has been pointed out as the most likely language of Tiwanaku.[5]

Cultural development and agriculture

The area around Tiwanaku may have been inhabited as early as 1500 BC as a small agricultural village.[6] Most research has studied the Tiwanaku IV and V periods between AD 300 and AD 1000, during which the polity grew significantly in power. During the time period between 300 BC and AD 300, Tiwanaku is thought to have been a moral and cosmological center to which many people made pilgrimages. Researchers believe it achieved this standing prior to expanding its powerful empire.[2] In 1945, Arthur Posnansky[7] estimated that Tiwanaku dated to 15,000 BC, based on his archaeoastronomical techniques. In the 21st century, experts decisively concluded Posnansky's dates were invalid and a "sorry example of misused archaeoastronomical evidence."[8]

Tiwanaku's location between the lake and dry highlands provided key resources of fish, wild birds, plants, and herding grounds for camelidae, particularly llamas.[9] The Titicaca Basin is the most productive environment in the area, with predictable and abundant rainfall. The Tiwanaku culture developed expanded farming. To the east, the Altiplano is an area of very dry arid land.[2] The Tiwanaku developed a distinctive farming technique known as "flooded-raised field" agriculture (suka kollus) to deal with the high-altitude Titicaca Basin. Such fields were used widely in regional agriculture, together with irrigated fields, pasture, terraced fields and qochas (artificial ponds).[2]

Artificially raised planting mounds are separated by shallow canals filled with water. The canals supply moisture for growing crops, but they also absorb heat from solar radiation during the day. This heat is gradually emitted during the bitterly cold nights and provide thermal insulation against the endemic frost in the region. Traces of similar landscape management have been found in the Llanos de Moxos region (Amazonian flood plains of the Moxos).[10] Over time, the canals also were used to farm edible fish. The resulting canal sludge was dredged for fertilizer. The fields grew to cover nearly the entire surface of the lake and although they were not uniform in size or shape, all had the same primary function.[10]

Though labor-intensive, suka kollus produce impressive yields. While traditional agriculture in the region typically yields 2.4 metric tons of potatoes per hectare, and modern agriculture (with artificial fertilizers and pesticides) yields about 14.5 metric tons per hectare, suka kollu agriculture yields an average of 21 tons per hectare.[2]

Modern agricultural researchers have re-introduced the technique of suka kollus. Significantly, the experimental suka kollus fields recreated in the 1980s by University of Chicago´s Alan Kolata and Oswaldo Rivera suffered only a 10% decrease in production following a 1988 freeze that killed 70-90% of the rest of the region's production.[11] Development by the Tiwanaku of this kind of protection against killing frosts in an agrarian civilization was invaluable to their growth.[11]

As the population grew, occupational niches developed, and people began to specialize in certain skills. There was an increase in artisans, who worked in pottery, jewelry and textiles. Like the later Incas, the Tiwanaku had few commercial or market institutions. Instead, the culture relied on elite redistribution.[12] That is, the elites of the empire controlled essentially all economic output, but were expected to provide each commoner with all the resources needed to perform his or her function. Selected occupations include agriculturists, herders, pastoralists, etc. Such separation of occupations was accompanied by hierarchichal stratification within the empire.[13]

The elites of Tiwanaku lived inside four walls that were surrounded by a moat. This moat, some believe, was to create the image of a sacred island. Inside the walls were many images devoted to human origin, which only the elites would see. Commoners may have only entered this structure for ceremonial purposes since it was home to the holiest of shrines.[2]

Rise and fall of Tiwanaku

Around AD 400 a state in the Titicaca basin began to develop and an urban capital was built at Tiwanaku.[14] Tiwanaku expanded its reaches into the Yungas and brought its culture and way of life to many other cultures in Peru, Bolivia, and the people of the Northern regions of Argentina and Chile. It was not exclusively a military or violent culture. In order to expand its reach, Tiwanaku used politics to create colonies, negotiate trade agreements (which made the other cultures rather dependent), and establish state cults.[15]

Others were drawn into the Tiwanaku empire due to religious beliefs, as it continued as a religious center. Force was rarely necessary for the empire to expand, but on the northern end of the Basin, resistance was present. There is evidence that bases of some statues were taken from other cultures and carried all the way back to the capital city of Tiwanaku, where the stones were placed in a subordinate position to the Gods of the Tiwanaku. They displayed the power their empire had over many.[16]

The Tiwanaku conducted human sacrifices on top of a building known as the Akipana. People were disemboweled and torn apart shortly after death and laid out for all to see. It is speculated that this ritual was a form of dedication to the gods. Research showed that one man who was sacrificed was not a native to the Titicaca Basin, leaving room to think that sacrifices were most likely not of people originally within the society.[2]

The community grew to urban proportions between 600 and 800, becoming an important regional power in the southern Andes. Early estimates figured that the city had covered approximately 6.5 square kilometers at its maximum, with between 15,000–30,000 inhabitants.[2] However, satellite imaging since the late 20th century has caused researchers to dramatically raise their estimates of population. They found that the extent of fossilized suka kollus across the three primary valleys of Tiwanaku appeared to have the capacity to support a population of between 285,000 and 1,482,000 people.[11]

The empire continued to grow, absorbing cultures rather than eradicating them. William H. Isbell states that "Tiahuanaco underwent a dramatic transformation between 600 and 700 that established new monumental standards for civic architecture and greatly increased the resident population."[17] Archaeologists note a noticeable adoption of Tiwanaku ceramics in the cultures that became part of the empire. Tiwanaku gained its power through the trade it implemented among the cities within its empire.[15] The elites gained their status by control of the surplus of food obtained from all regions, which they redistributed among all the people. Control of llama herds became very significant to Tiwanaku. The animals were essential for transporting crops and goods between the center and periphery of the empire. The animals may also have symbolized the distance between the commoners and the elites.

The elites' power continued to grow along with the surplus of resources until about 950. At this time a dramatic shift in climate occurred,[2] as is typical for the region.[18][19] A significant drop in precipitation occurred in the Titicaca Basin, and some archaeologists suggest a great drought occurred. As the rain was reduced, many of the cities furthest away from Lake Titicaca began to produce fewer crops to give to the elites. As the surplus of food dropped, the elites' power began to fall. Due to the resiliency of the raised fields, the capital city became the last place of agricultural production. With continued drought, people died or moved elsewhere. Tiwanaku disappeared around 1000. The land was not inhabited again for many years.[2] In isolated places, some remnants of the Tiwanaku people, such as the Uros, may be direct descendants of the people.

Beyond the northern frontier of the Tiwanaku state, a new power started to emerge in the beginning of the 13th century, the Inca Empire.

In 1445 Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui (the ninth Inca) began conquest of the Titicaca regions. He incorporated and developed what was left from the Tiwanaku patterns of culture, and the Inca officials were superimposed upon the existing local officials. Quechua was made the official language and sun worship the official religion. So, the last traces of the Tiwanaku civilization were integrated or abandoned.

Architecture and art

Tiwanaku monumental architecture is characterized by large stones of exceptional workmanship. In contrast to the masonry style of the later Inca, Tiwanaku stone architecture usually employs rectangular ashlar blocks laid in regular courses. Their monumental structures were frequently fitted with elaborate drainage systems. The drainage systems of the Akapana and Pumapunku structures include conduits composed of red sandstone blocks held together by ternary (copper/arsenic/nickel) bronze architectural cramps. The I-shaped architectural cramps of the Akapana were created by cold hammering of ingots. In contrast, the cramps of the Pumapunku were created by pouring molten metal into I-shaped sockets.[20] The blocks have flat faces that do not need to be fitted upon placement because the grooves make it possible for the blocks to be shifted by ropes into place. The main architectural appeal of the site comes from the carved images and designs on some of these blocks, carved doorways, and giant stone monoliths.[21]

The quarries that supplied the stone blocks for Tiwanaku lie at significant distances from this site. The red sandstone used in this site's structures has been determined by petrographic analysis to come from a quarry 10 kilometers away—a remarkable distance considering that the largest of these stones weighs 131 metric tons.[22] The green andesite stones that were used to create the most elaborate carvings and monoliths originate from the Copacabana peninsula, located across Lake Titicaca.[22] One theory is that these giant andesite stones, which weigh over 40 tons, were transported some 90 kilometers across Lake Titicaca on reed boats, then laboriously dragged another 10 kilometers to the city.[23]

Structures

The structures that have been excavated at Tiwanaku include the Akapana, Akapana East, and Pumapunku stepped platforms, the Kalasasaya, the Kheri Kala, and Putuni enclosures, and the Semi-Subterranean Temple. These may be visited by the public.

The Akapana is an approximately cross-shaped pyramidal structure that is 257 m wide, 197 m broad at its maximum, and 16.5 m tall. At its center appears to have been a sunken court. This was nearly destroyed by a deep looters excavation that extends from the center of this structure to its eastern side. Material from the looters excavation was dumped off the eastern side of the Akapana. A staircase with sculptures is present on its western side. Possible residential complexes might have occupied both the northeast and southeast corners of this structure.

Originally, the Akapana was thought to have been made from a modified hill. Twenty-first century studies have shown that it is a manmade earthen mound, faced with a mixture of large and small stone blocks. The dirt comprising Akapana appears to have been excavated from the "moat" that surrounds the site.[21] The largest stone block within the Akapana, made of andesite, is estimated to weigh 65.70 metric tons.[22] The structure was possibly for the shaman-puma relationship or transformation through shape shifting. Tenon puma and human heads stud the upper terraces.[21]

The Akapana East was built on the eastern side of early Tiwanaku. Later it was considered a boundary between the ceremonial center and the urban area. It was made of a thick, prepared floor of sand and clay, which supported a group of buildings. Yellow and red clay were used in different areas for what seems like aesthetic purposes. It was swept clean of all domestic refuse, signaling its great importance to the culture.[21]

The Pumapunku is a man-made platform built on an east-west axis like the Akapana. It is a rectangular terraced earthen mound faced with megalithic blocks. It is 167.36 m wide along its north-south axis and 116.7 m broad along its east-west axis, and is 5 m tall. Identical 20-meter wide projections extend 27.6 meters north and south from the northeast and southeast corners of the Pumapunku. Walled and unwalled courts and an esplanade are associated with this structure.

A prominent feature of the Pumapunku is a large stone terrace; it is 6.75 by 38.72 meters in dimension and paved with large stone blocks. It is called the "Plataforma Lítica". The Plataforma Lítica contains the largest stone block found in the Tiwanaku Site.[22][24] Ponce Sangines[22] the block is estimated to weigh 131 metric tons. The second largest stone block found within the Pumapunku is estimated to be 85 metric tons.[22][24]

.jpg)

The Kalasasaya is a large courtyard over three hundred feet long, outlined by a high gateway. It is located to the north of the Akapana and west of the Semi-Subterranean Temple. Within the courtyard is where explorers found the Gateway of the Sun. Since the late 20th century, researchers have theorized that this was not the gateway's original location. Near the courtyard is the Semi-Subterranean Temple; a square sunken courtyard that is unique for its north-south rather than east-west axis.[25] The walls are covered with tenon heads of many different styles, suggesting that the structure was reused for different purposes over time.[26] It was built with walls of sandstone pillars and smaller blocks of Ashlar masonry.[26][27] The largest stone block in the Kalasasaya is estimated to weigh 26.95 metric tons.[22]

Within many of the site's structures are impressive gateways; the ones of monumental scale are placed on artificial mounds, platforms, or sunken courts. Many gateways show iconography of "Staffed Gods." This iconography also is used on some oversized vessels, indicating an importance to the culture. This iconography is most present on the Gateway of the Sun.[28]

The Gateway of the Sun and others located at Pumapunku are not complete. They are missing part of a typical recessed frame known as a chambranle, which typically have sockets for clamps to support later additions. These architectural examples, as well as the recently discovered Akapana Gate, have a unique detail and demonstrate high skill in stone-cutting. This reveals a knowledge of descriptive geometry. The regularity of elements suggest they are part of a system of proportions.

Many theories for the skill of Tiwanaku's architectural construction have been proposed. One is that they used a luk’a, which is a standard measurement of about sixty centimeters. Another argument is for the Pythagorean Ratio. This idea calls for right triangles at a ratio of five to four to three used in the gateways to measure all parts. Lastly Protzen and Nair argue that Tiwanaku had a system set for individual elements dependent on context and composition. This is shown in the construction of similar gateways ranging from diminutive to monumental size, proving that scaling factors did not affect proportion. With each added element, the individual pieces were shifted to fit together.[29]

Relationship with Wari

The Tiwanaku shared domination of the Middle Horizon with the Wari, based primarily in central and south Peru, although found to have built important sites in the north as well (Cerro Papato ruins). Their culture rose and fell around the same time; it was centered 500 miles north in the southern highlands of Peru. The relationship between the two empires is unknown. Definite interaction between the two is proved by their shared iconography in art. Significant elements of both of these styles (the split eye, trophy heads, and staff-bearing profile figures, for example) seem to have been derived from that of the earlier Pukara culture in the northern Titicaca Basin. The Tiwanaku created a powerful ideology, using previous Andean icons that were widespread throughout their sphere of influence. They used extensive trade routes and shamanistic art. Tiwanaku art consisted of legible, outlined figures depicted in curvilinear style with a naturalistic manner, while Wari art used the same symbols in a more abstract, rectilinear style with a militaristic style.[30]

Tiwanaku sculpture is comprised typically of blocky, column-like figures with huge, flat square eyes, and detailed with shallow relief carving. They are often holding ritual objects, such as the Ponce Stela or the Bennett Monolith. Some have been found holding severed heads, such as the figure on the Akapana, who possibly represents a puma-shaman. These images suggest the culture practiced ritual human beheading. As additional evidence, headless skeletons have been found under the Akapana.

They also used ceramics and textiles, composed of bright colors and stepped patterns. An important ceramic artifact is the qiru, a drinking cup that was ritually smashed after ceremonies and placed with other goods in burials. As the empire expanded, the style of ceramics changed. The earliest ceramics were "coarsely polished, deeply incised brownware and a burnished polychrome incised ware". Later the Qeya style became popular during the Tiwanaku III phase, "Typified by vessels of a soft, light brown ceramic paste". These ceramics included libation bowls and bulbous-bottom vases.[31]

Examples of textiles are tapestries and tunics. The objects typically depicted herders, effigies, trophy heads, sacrificial victims, and felines. Such small, portable objects of ritual religious meaning were a key to spreading religion and influence from the main site to the satellite centers. They were created in wood, engraved bone, and cloth. They depicted puma and jaguar effigies, incense burners, carved wooden hallucinogenic snuff tablets, and human portrait vessels. Like the Moche, Tiwanaku portraits expressed individual characteristics.[32]

Religion

What is known of Tiwanaku religious beliefs is based on archaeological interpretation and some myths, which may have been passed down to the Incas and the Spanish. They seem to have worshipped many gods, perhaps centered on agriculture. One of the most important gods was Viracocha, the god of action, shaper of many worlds, and destroyer of many worlds. He created people, with two servants, on a great piece of rock. Then he drew sections on the rock and sent his servants to name the tribes in those areas. In Tiwanaku, he created the people out of rock and brought life to them through the earth. The Tiwanaku believed that Viracocha created giants to move the massive stones that comprise much of their archaeology, but then grew unhappy with the giants and created a flood to destroy them.

Viracocha is carved into the noted Gateway of the Sun, to overlook his people and lands. The Gateway of the Sun is a monolithic structure of regular, non-monumental size. Its dimensions suggest that other regularly sized buildings existed at the site. It was found at Kalasasaya, but due to the similarity of other gateways found at Pumapunku, it is thought to have been originally part of a series of doorways there.[2]

It is recognized for its singular, great frieze. This is thought to represent a main deity figure surrounded by either calendar signs or natural forces for agricultural worship. Along with Viracocha, another statue is in the Gateway of the Sun. This statue is believed to be associated with the weather:

a celestial high god that personified various elements of natural forces intimately associated the productive potential of altiplano ecology: the sun, wind, rain, hail – in brief, a personification of atmospherics that most directly affect agricultural production in either a positive or negative manner[2]

It has twelve faces covered by a solar mask, and at the base thirty running or kneeling figures.[2] Some scientists believe that this statue is a representation of the calendar with twelve months and thirty days in each month.[2]

Other evidence points to a system of ancestor worship at Tiwanaku. The preservation, use, and reconfiguration of mummy bundles and skeletal remains, as with the later Inca, may suggest that this is the case.[2] Later cultures within the area made use of large "above ground burial chambers for the social elite... known as "chullpas".[2] Similar, though smaller, structures were found within the site of Tiwanaku.[2]

Kolata suggests that, like the later Inka, the inhabitants of Tiwanaku may have practiced similar rituals and rites in relation to the dead. The Akapana East Building has evidence of ancestor burial. The human remains at Akapana East seem to be less for show and more for proper burial. The skeletons show many cut marks that were most likely made by defleshing or excarnation after death. The remains were then bundled up and buried rather than left out in the open.[16]

Archaeology

As the site has suffered from looting and amateur excavations since shortly after Tiwanaku's fall, archeologists must try to interpret it knowing that materials have been jumbled and destroyed. This destruction continued during the Spanish conquest and colonial period, and during 19th century and the early 20th century. Other damage was committed by people quarrying stone for building and railroad construction, and target practice by military personnel.

No standing buildings have survived at the modern site. Only public, non-domestic foundations remain, with poorly reconstructed walls. The ashlar blocks used in many of these structures were mass-produced in similar styles so that they could possibly be used for multiple purposes. Throughout the period of the site, certain buildings changed purposes, causing a mix of artifacts found today.[29]

Detailed study of Tiwanaku began on a small scale in the mid-nineteenth century. In the 1860s, Ephraim George Squier visited the ruins and later published maps and sketches completed during his visit. German geologist Alphons Stübel spent nine days in Tiwanaku in 1876, creating a map of the site based on careful measurements. He also made sketches and created paper impressions of carvings and other architectural features. A book containing major photographic documentation was published in 1892 by engineer B. von Grumbkow. With commentary by archaeologist Max Uhle, this was the first in-depth scientific account of the ruins.

- Pictures of archaeological excavations in 1903

-

Stairs of Kalasasaya (1903)

-

Temple of Kalasasaya (1903)

-

_1903-1904.jpg)

Gate of the Sun (1903)

-

Gate of the Sun, Rear View (1903)

Contemporary excavation and restoration

In the 1960s, the government initiated an effort to restore the site and reconstruct part of it. The walls of the Kalasasaya are almost all reconstructed. The original stones making up the Kalasasaya would have resembled a more "Stonehenge"-like style, spaced evenly apart and standing straight up. The reconstruction was not sufficiently based on research; for instance, a new wall was built around Kalasasaya. The reconstruction does not have as high quality of stonework as was present in Tiwanaku.[26] As noted, the Gateway of the Sun, now in the Kalasasaya, was moved from its original location.[2]

Modern, academically sound archaeological excavations were performed from 1978 through the 1990s by University of Chicago anthropologist Alan Kolata and his Bolivian counterpart, Oswaldo Rivera. Among their contributions are the rediscovery of the suka kollus, accurate dating of the civilization's growth and influence, and evidence for a drought-based collapse of the Tiwanaku civilization.

Archaeologists such as Paul Goldstein have argued that the Tiwanaku empire ranged outside of the altiplano area and into the Moquegua Valley in Peru. Excavations at Omo settlements show signs of similar architecture characteristic of Tiwanaku, such as a temple and terraced mound.[25] Evidence of similar types of cranial deformation in burials between the Omo site and the main site of Tiwanaku is also being used for this argument.[33]

Today Tiwanaku has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, administered by the Bolivian government.

Recently, the Department of Archaeology of Bolivia (DINAR, directed by Javier Escalante) has been conducting excavations on the Akapana pyramid. The Proyecto Arqueologico Pumapunku-Akapana (PAPA, or Pumapunku-Akapana Archaeological Project) run by the University of Pennsylvania, has been excavating in the area surrounding the pyramid for the past few years, and also conducting Ground Penetrating Radar surveys of the area.

In former years, an archaeological field school offered through Harvard's Summer School Program, conducted in the residential area outside the monumental core, has provoked controversy amongst local archaeologists.[34] The program was directed by Dr. Gary Urton,[35] of Harvard, who was an expert in quipu, and Dr. Alexei Vranich of the University of Pennsylvania. The controversy was over allowing a team of untrained students to work on the site, even under professional supervision. It was so important that only certified professional archaeologists with documented funding were allowed access. The controversy was charged with nationalistic and political undertones.[36] The Harvard field school lasted for three years, beginning in 2004 and ending in 2007. The project was not renewed in subsequent years, nor was permission sought to do so.

In 2009 state-sponsored restoration work on the Akapana pyramid was halted due to a complaint from UNESCO. The restoration had consisted of facing the pyramid with adobe, although researchers had not established this as appropriate.[37][38]

Lukurmata

Lukurmata was a secondary site near Lake Titicaca in Bolivia. First established nearly two thousand years ago, it grew to be a major ceremonial center in the Tiwanaku state, a polity that dominated the south-central Andes from 400 to 1200. After the Tiwanaku state collapsed, Lukurmata rapidly declined, becoming once again a small village. The site shows evidence of extensive occupation that antedates the Tiwanakan civilization.

See also

- Kimsa Chata

- Las Ánimas complex

- List of megalithic sites

- Wari culture

- Puma Punku

References

- ↑ "269", WHC, Unesco.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 Kolata, Alan L. (December 11, 1993). The Tiwanaku: Portrait of an Andean Civilization. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-55786-183-2. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ↑ Hughes, Holly (October 20, 2008). Places to See Before They Disappear. 500 Places. Frommers. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-470-18986-3. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ↑ "Profile: Fabricio R. Santos – The Genographic project". Genographic Project. National Geographic. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ↑ Heggarty, P; Beresford-Jones, D (2013). "Andes: linguistic history". In Ness, I; P, Bellwood. The Encyclopedia of Global Human Migration. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 401–9.

- ↑ Fagan, Brian M (2001), The Seventy Great Mysteries of the Ancient World: Unlocking the Secrets of Past Civilizations, New York: Thames & Hudson.

- ↑ Posnansky, A (1945), Tihuanacu, the Cradle of American Man I–II, James F. Sheaver transl, New York: JJ Augustin; Vols. III–IV, La Paz, Bolivia: Minister of Education

- ↑ Kelley, DH; Milone, EF (2002), Exploring Ancient Skies: An Encyclopedic Survey of Archaeoastronomy, New York: Springer Science+Business, 616 pp.

- ↑ Bruhns, K (1994), Ancient South America, Cambridge University Press, 424 pp.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Kolata, Alan L (1986), "The Agricultural Foundations of the Tiwanaku State: A View from the Heartland", American Antiquity 51: 748–62, doi:10.2307/280863.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Kolata, Alan L. Valley of the Spirits: A Journey into the Lost Realm of the Aymara, Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, 1996.

- ↑ Smith, Michael E. (2004), "The Archaeology of Ancient Economies," Annu. Rev. Anthrop. 33: 73-102.

- ↑ Bahn, Paul G. Lost Cities. New York: Welcome Rain, 1999.

- ↑ Stanish, Charles (2003). Ancient Titicaca: The Evolution of Complex Society in Southern Peru and Northern Bolivia. University of California Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-520-23245-7.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 McAndrews, Timothy L. et al. 'Regional Settlement Patterns in the Tiwanaku Valley of Bolivia'. Journal of Field Archaeology 24 (1997): 67–83.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Blom, Deborah E. and John W. Janusek. "Making Place: Humans as Dedications in Tiwanaku", World Archaeology (2004): 123–41.

- ↑ Isbell, William H. 'Wari and Tiwanaku: International Identities in the Central Andean Middle Horizon'. 731-751.

- ↑ "Lake Titicaca study sheds new light on global climate change", Stanford News Service, 25 January 2001.

- ↑ Baker PA, PA; Dunbar, RB (2001-01-26). et al.. "The history of South American tropical precipitation for the past 25,000 years". Science 291 (5504): 640–3. doi:10.1126/science.291.5504.640. PMID 11158674.

- ↑ Lechtman, Heather N., MacFarlane, and Andrew W., 2005, "La metalurgia del bronce en los Andes Sur Centrales: Tiwanaku y San Pedro de Atacama". Estudios Atacameños, vol. 30, pp. 7-27.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Isbell, W. H., 2004, Palaces and Politics in the Andean Middle Horizon. in S. T. Evans and J. Pillsbury, eds., pp. 191-246. Palaces of the Ancient New World. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 22.6 Ponce Sanginés, C. and G. M. Terrazas, 1970, Acerca De La Procedencia Del Material Lítico De Los Monumentos De Tiwanaku. Publication no. 21. Academia Nacional de Ciencias de Bolivia.

- ↑ Harmon, P., 2002, "Experimental Archaeology, Interactive Dig, Archaeology Magazine, "Online Excavations" web page, Archaeology magazine.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Vranich, A., 1999, Interpreting the Meaning of Ritual Spaces: The Temple Complex of Pumapunku, Tiwanaku, Bolivia, Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pennsylvania.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Goldstein, Paul (1993). Tiwanaku Temples and State Expansion: A Tiwanaku Sunken-Court Temple in Moquegua, Peru.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Browman, D. L., 1981, "New light on Andean Tiwanaku," New Scientist vol. 69, no. 4, pp. 408-419.

- ↑ Coe, Michael, Dean Snow, and Elizabeth Benson, 1986 Atlas of Ancient America p. 190

- ↑ Silverman, Helaine Andean Archaeology Volume 2. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing, 2004

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Protzen, J.-P., and S. E. Nair, 2000, "On Reconstructing Tiwanaku Architecture": The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 59, no., 3, pp. 358-371.

- ↑ Stone-Miller, Rebecca (1995 and 2002). Art of the Andes: from Chavin to Inca. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Bray, Tamara L. The Archaeology and Politics of Food and Feasting in Early States and Empires, New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2003

- ↑ Rodman, Amy Oakland (1992). Textiles and Ethnicity: Tiwanaku in San Pedro de Atacama.

- ↑ Hoshower, Lisa M. (1995). Artificial Cranial Deformation at the Omo M10 Site: A Tiwanaku Complex from the Moquegua Valley, Peru.

- ↑ Lémuz, C (2007), "Buenos Negocios, ¿Buena Arqueologia?", Crítica Arqueológica Boliviana [Bolivian archæological critic] (World Wide Web log) (in Spanish).

- ↑ "Program in Tiwanaku, Bolivia", Summer School Archives, Harvard University, 2005.

- ↑ Kojan, David; Angelo, Dante, "Dominant narratives, social violence and the practice of Bolivian archaeology", Journal of Social Archaeology 5 (3): 383–408, doi:10.1177/1469605305057585.

- ↑ Carroll, Rory (20 October 2009). "Makeover may lose Bolivian pyramid its world heritage site listing". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Pyramid may lose World Heritage status after renovation fiasco". Sydney Morning Herald. October 20, 2009.

Bibliography

- Bermann, Marc Lukurmata Princeton University Press (1994) ISBN 978-0-691-03359-4.

- Bruhns, Karen Olsen, Ancient South America, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, c. 1994.

- Goldstein, Paul, "Tiwanaku Temples and State Expansion: A Tiwanaku Sunken-Court Temple in Moduegua, Peru", Latin American Antiquity, Vol. 4, No. 1 (March 1993), pp. 22–47, Society for American Archaeology.

- Hoshower, Lisa M., Jane E. Buikstra, Paul S. Goldstein, and Ann D. Webster, "Artificial Cranial Deformation at the Omo M10 Site: A Tiwanaku Complex from the Moquegua Valley, Peru", Latin American Antiquity, Vol. 6, No. 2 (June, 1995) pp. 145–64, Society for American Archaeology.

- Kolata, Alan L., "The Agricultural Foundations of the Tiwanaku State: A View from the Heartland", American Antiquity, Vol. 51, No. 4 (October 1986), pp. 748–762, Society for American Archaeology.

- Kolata, Alan L (June 1991), "The Technology and Organization of Agricultural Production in the Tiwanaku State", Latin American Antiquity (Society for American Archaeology) 2 (2): 99–125, doi:10.2307/972273.

- Protzen, Jean-Pierre and Stella E. Nair, "On Reconstructing Tiwanaku Architecture", The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 59, No. 3 (September 2000), pp. 358–71, Society of Architectural Historians.

- Reinhard, Johan, "Chavin and Tiahuanaco: A New Look at Two Andean Ceremonial Centers." National Geographic Research 1(3): 395–422, 1985.

- ——— (1990), "Tiahuanaco, Sacred Center of the Andes", in McFarren, Peter, An Insider's Guide to Bolivia, La Paz, pp. 151–81.

- ——— (1992), "Tiwanaku: Ensayo sobre su cosmovisión" [Tiwanaku: essay on its cosmovision], Revista Pumapunku (in Spanish) 2: 8–66.

- Stone-Miller, Rebecca (2002) [c. 1995], Art of the Andes: from Chavin to Inca, London: Thames & Hudson.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tiwanaku. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Tiwanaku. |

| Library resources about Tiwanaku |

- Map of Ingavi Province, Agua en Bolivia, CGIAB, archived from the original on Apr 18, 2009, retrieved September 22, 2013.

- "Tiwanaku: Spiritual and Political Centre of the Tiwanaku Culture", World Heritage List, World Heritage Centre, UNESCO, retrieved September 22, 2013.

- Daily Life at Tiwanaku, Archæology student, archived from the original on May 22, 2010, retrieved September 22, 2013.

- "Revealing Ancient Bolivia", Archaeology Magazine (Archaeological Institute of America), 2004, retrieved September 22, 2013.

- "Geophysics and Geomatics at Tiwanaku", Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies, Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas, retrieved September 22, 2013.

- Heinrich, P (2008), "Tiwanaku (Tiahuanaco) Site Bibliography", Papers, Hall of Ma’at.

- Higueros, A (1999), "Archaeological Research on the Tiwanaku polity in Peru and Bolivia", Arqueologia Andina y Tiwanaku.

| ||||||||