Tirari Desert

| Tirari | |

| Desert | |

NASA satellite image, 2006 | |

| Country | Australia |

|---|---|

| State | South Australia |

| Region | Far North |

| Area | 15,250 km2 (5,888 sq mi) |

| Biome | Desert |

| Wikimedia Commons: Tirari Desert | |

The Tirari Desert is a 15,250 square kilometres (5,888 sq mi)[1] desert in the eastern part of the Far North region of South Australia.

Location and description

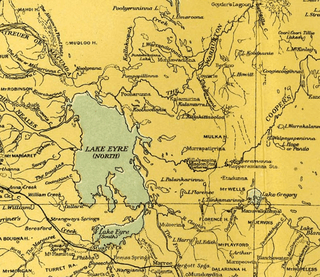

The Tirari Desert features salt lakes and large north-south running sand dunes.[2][3] It is located partly within the Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre National Park.[4] It lies mainly to the east of Lake Eyre North. Cooper Creek runs through the centre of the desert.

The adjacent deserts of the area include Simpson Desert which lies to the north while the Strzelecki Desert is to the east and the Sturt Stony Desert runs aligned with the Birdsville track to the north east.

The desert experiences harsh conditions with high temperatures and very low rainfall (mean annual rainfall is below 125 millimetres (4.9 in)).[5]

Access and stations

The main vehicular access to the desert is via the unpaved Birdsville Track which runs northwards from Marree to Birdsville. The Mungerannie Hotel is the only location between the two towns that provides services.[6]

The Tirari Desert region has a number of large cattle stations which are stopping points on the Channel Country aviation mail run.[7]

Dulkaninna Station has been run by the same family for 110 years, has 2,000 cattle and breeds horses and kelpies.[7] Etadunna Station to the north is a 1-million-acre (4,000 km2) cattle station with 2500 cattle.[7] The station environs include a number of heritage sites include Bucaltaninna Homestead ruins, the Woolshed ruins and Canny Trig Point (also known as Milner's Pile) and the state heritage-registered Killalpaninna Mission site.[8]

Further north again is Mulka Station which also has a number of heritage sites including homestead ruins at Apatoongannie, Old Mulka and Ooroowillannie. The Mulka Store ruins is listed on the South Australian state register of heritage places.[8]

Vegetation

The vegetation of the dunefields of the Tirari Desert is dominated by either Sandhill Wattle (Acacia ligulata) or Sandhill Cane-grass (Zygochloa paradoxa) which occur on the crests and slopes of dunes. Tall, open shrubland also occurs on the slopes.[9] The otherwise sparsely vegetated dunefields become covered by a carpet of grasses, herbs and colourful flowering plants following rains.[9]

The interdune soil types and hence the vegetation, varies with the dune spacing. Closer spaced dunes result in sandy valleys that have similar vegetation to the dune sides while widely spaced dunes are separated by gibber or flood plains, each supporting particular vegetation communities.[9]

The vegetation on the floodplains varies with the capacity of the land to retain floodwaters, and the frequency of inundation. In drier areas, species including Old Man Saltbush (Atriplex nummularia), Cottonbush (Maireana aphylla) and Queensland Bluebush (Chenopodium auricomum) form a sparse, open shrubland, whereas swamps and depressions are frequently associated with Swamp Cane-grass (Eragrostis australasica) and Lignum (Muehlenbeckia florulenta).[10]

The intermittent watercourses and permanent waterholes associated with tributaries of Cooper Creek support woodland dominated by River Red Gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) and Coolibah (Eucalyptus coolabah).[10]

As at 2008, the Tirari Desert is included in biogeographic regions (IBRA) SSD3: Dieri, part of the Simpson Strzelecki Dunefields (SSD) Region.[11] The desert is also part of the Tirari-Sturt stony desert ecoregion.[12]

Fossils

The desert incorporates the Lake Ngapakaldi to Lake Palankarinna Fossil Area, a 3.5 square kilometres (1.4 sq mi) area on Australia's Register of the National Estate with significant Tertiary period vertebrate fossils.[13]

History

The area was first explored by Europeans in 1866 and was previously settled by a small tribe of Aboriginals.

Dieri people

The Tirari Desert has been part of the Dieri people's native title claim.[14][15] The Australian anthropologist Norman Tindale reported a small tribe now extinct which he referred to as the Tirari. They were located at the eastern shore of Lake Eyre from Muloorina north to Warburton River; east to Killalapaninna. Tindale disagreed with the earlier findings of Alfred William Howitt that these people were a horde of the Dieri as the language spoken was different from Dieri. Since Tindale's work was published, much of the data relating to Aboriginal language group distribution and definition has undergone revision since 1974. Tindale's focus was to depict Aboriginal tribal distribution at the time of European contact.[16]

Missions

In the 1860s two Aboriginal missions were established near the Cooper Creek crossing of the Birdsville Track. The Moravians established a short-lived mission at Lake Kopperamanna in 1866. This was closed in 1869 due to drought conditions and poor relations with the local indigenous community.[17][18]

Bethesda Mission was established by German Lutherans at nearby Lake Killalpaninna around the same period and, after also being abandoned for a short time, was re-established and by the 1880s it resembled a small town with more than 20 dwellings including a church. At this time, it had a population of "several hundred aborigines and a dozen whites".[17] Primarily financed by sheep grazing, the mission closed in 1917 due to the effects of drought and rabbit plagues. Currently, there is little evidence of the settlement other than a small cemetery and some remnant timber posts.[17]

European exploration

On an 1866 expedition to determine the northern limit of Lake Eyre, Peter Egerton Warburton approached the desert from the west and followed the upstream course of what is now known as the Warburton River, but which he incorrectly believed was Cooper Creek.[19] In 1874 another expedition, led by James William Lewis, again followed the river upstream to the Queensland border, retracing the route on the return journey and then headed south to the Kopperamanna mission.[19] Subsequently, they followed the course of Cooper Creek to conduct a survey of the east shore of Lake Eyre.[19] Lewis, in a later account of his expedition, said of the lake "I sincerely trust I may never see it again; it is useless in every respect, and the very sight of it creates thirst in man and beast."[19][20]

See also

- Deserts of Australia

- Lake Eyre Basin

- List of deserts by area

References

- ↑ Geosciences Australia – Deserts

- ↑ "Lake Eyre 1". South Australian Film Corporation. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ↑ Callen, R. A.; Nanson, G. C. (1992). "Formation and age of dunes in the Lake Eyre Depocentres". International Journal of Earth Sciences 81 (2): 589–593. doi:10.1007/bf01828619.

- ↑ "Lake Eyre National Park". Department for Environment and Heritage. 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ↑ Fitzsimmons, Kathryn E. (30 October 2007). "Morphological variability in the linear dunefields of the Strzelecki and Tirari Deserts, Australia". Geomorphology 91 (1–2): 146–160. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2007.02.004.

- ↑ "The Birdsville Track". Outback Australia. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "West Wing Aviation Mail Runs". Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks" (PDF). Department for Environment and Heritage. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "South Australian Arid Lands Biodiversity Strategy Draft" (pdf (2.67MB—48 pages)). The Department for Environment and Heritage (Federal Government of Australia) and South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board. p. 34. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "South Australian Arid Lands Biodiversity Strategy Draft" (pdf (2.67MB—48 pages)). The Department for Environment and Heritage (Federal Government of Australia) and South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board. p. 17. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- ↑ "South Australian Arid Lands Biodiversity Strategy Draft" (pdf (2.67MB—48 pages)). The Department for Environment and Heritage (Federal Government of Australia) and South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board. p. 9. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- ↑ World Wildlife Fund (2001). "Tirari-Sturt stony desert". WildWorld Ecoregion Profile. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 2010-03-08.

- ↑ "Lake Ngapakaldi to Lake Palankarinna Fossil Area". aussieheritage.com.au. 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ↑ "Claimant application summary". National Native Title Tribunal. 2006. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ↑ South Australia native title claim. Edward Landers (2001)Dieri People native title claim[cartographic material] : NNTT SC97/004 and Federal Court SG6017/1998. South Australia. Dept. for Environment and Heritage. Environmental and Geographic Information Scale ca. 1:550 000 (E 137⁰00'--E 141⁰30'/S 26⁰30'--S 30⁰10') [Adelaide] : Environmental and Geographic Information, Dept. for Environment and Heritage, Map of Tirari Desert region including Lake Eyre and Strzelecki Recreational Reserve. "Native title claim boundary sourced from NNTT and current as at 27 February 2001". "Mapped: 9 July 2001".

- ↑ Tindale, Norman (16 December 2003) [1974]. "Tirari (SA)". Aboriginal Tribes of Australia (1974). South Australian Museum. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Van Driesum, Rob; Paul Harding; Denis O'Byrne; Pete Cruttenden; Mic Looby (2002). Outback Australia: Kakadu, Uluru and Kangaroos. Lonely Planet. ISBN 1-86450-187-1. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ↑ "Moravian Missionary Brothers". SA Memory. State Library (South Australia). Archived from the original on 2008-07-22. Retrieved 2008-09-27.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 "Taking it to the edge: Land: JW Lewis : Lake Eyre". Taking it to the edge - exploration in South Australia. State Library (South Australia). Retrieved 2008-09-27.

- ↑ "South Australian Parliamentary Paper no. 19". 1876. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tirari Desert. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||