Tight span

In metric geometry, the metric envelope or tight span of a metric space M is an injective metric space into which M can be embedded. In some sense it consists of all points "between" the points of M, analogous to the convex hull of a point set in a Euclidean space. The tight span is also sometimes known as the injective envelope or hyperconvex hull of M. It has also been called the injective hull, but should not be confused with the injective hull of a module in algebra, a concept with a similar description relative to the category of R-modules rather than metric spaces.

The tight span was first described by Isbell (1964), and it was studied and applied by Holsztyński in the 1960s. It was later independently rediscovered by Dress (1984) and Chrobak & Larmore (1994); see Chepoi (1997) for this history. The tight span is one of the central constructions of T-theory.

Definition

The tight span of a finite metric space can be defined as follows. Let (X,d) be a metric space, with X finite, and let T(X) be the set of functions f from X to R such that

- For any x, y in X, f(x) + f(y) ≥ d(x,y), and

- For each x in X, there exists y in X such that f(x) + f(y) = d(x,y).

In particular (taking x = y in property 1 above) f(x) ≥ 0 for all x. One way to interpret the first requirement above is that f defines a set of possible distances from some new point to the points in X that must satisfy the triangle inequality together with the distances in (X,d). The second requirement states that none of these distances can be reduced without violating the triangle inequality.

Given two functions f and g in T(X), define δ(f,g) = max |f(x)-g(x)|; if we view T(X) as a subset of a vector space R|X| then this is the usual L∞ distance between vectors. The tight span of X is the metric space (T(X),δ). There is an isometric embedding of X into its tight span, given by mapping any x into the function fx(y) = d(x,y). It is straightforward to expand the definition of δ using the triangle inequality for X to show that the distance between any two points of X is equal to the distance between the corresponding points in the tight span.

The definition above embeds the tight span of a set of n points into a space of dimension n. However, Develin (2006) showed that, with a suitable general position assumption on the metric, this definition leads to a space with dimension between n/3 and n/2. Develin & Sturmfels (2004) provide an alternative definition of the tight span of a finite metric space, as the tropical convex hull of the vectors of distances from each point to each other point in the space.

For general (finite and infinite) metric spaces, the tight span may be defined using a modified version of property 2 in the definition above stating that inf f(x) + f(y) - d(x,y) = 0.[1] An alternative definition based on the notion of a metric space aimed at its subspace was described by Holsztyński (1968), who proved that the injective envelope of a Banach space, in the category of Banach spaces, coincides (after forgetting the linear structure) with the tight span. This theorem allows to reduce certain problems from arbitrary Banach spaces to Banach spaces of the form C(X), where X is a compact space.

Example

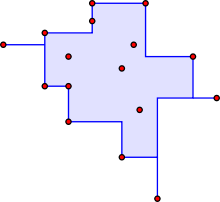

The figure shows a set X of 16 points in the plane; to form a finite metric space from these points, we use the Manhattan distance (L1 metric).[2] The blue region shown in the figure is the orthogonal convex hull, the set of points z such that each of the four closed quadrants with z as apex contains a point of X. Any such point z corresponds to a point of the tight span: the function f(x) corresponding to a point z is f(x) = d(z,x). A function of this form satisfies property 1 of the tight span for any z in the Manhattan-metric plane, by the triangle inequality for the Manhattan metric. To show property 2 of the tight span, consider some point x in X; we must find y in X such that f(x)+f(y)=d(x,y). But if x is in one of the four quadrants having z as apex, y can be taken as any point in the opposite quadrant, so property 2 is satisfied as well. Conversely it can be shown that every point of the tight span corresponds in this way to a point in the orthogonal convex hull of these points. However, for point sets with the Manhattan metric in higher dimensions, and for planar point sets with disconnected orthogonal hulls, the tight span differs from the orthogonal convex hull.

Applications

- Dress, Huber & Moulton (2001) describe applications of the tight span in reconstructing evolutionary trees from biological data.

- The tight span serves a role in several online algorithms for the K-server problem.[3]

- Sturmfels & Yu (2004) uses the tight span to classify metric spaces on up to six points.

- Chepoi (1997) uses the tight span to prove results about packing cut metrics into more general finite metric spaces.

Notes

- ↑ See e.g. Dress, Huber & Moulton (2001).

- ↑ In two dimensions, the Manhattan distance is isometric after rotation and scaling to the L∞ distance, so with this metric the plane is itself injective, but this equivalence between L1 and L∞ does not hold in higher dimensions.

- ↑ Chrobak & Larmore (1994).

References

- Chepoi, Victor (1997), "A TX approach to some results on cuts and metrics", Advances in Applied Mathematics 19 (4): 453–470, doi:10.1006/aama.1997.0549.

- Chrobak, Marek; Larmore, Lawrence L. (1994), "Generosity helps or an 11-competitive algorithm for three servers", Journal of Algorithms 16 (2): 234–263, doi:10.1006/jagm.1994.1011.

- Develin, Mike (2006), "Dimensions of tight spans", Annals of Combinatorics 10 (1): 53–61, arXiv:math.CO/0407317, doi:10.1007/s00026-006-0273-y.

- Develin, Mike; Sturmfels, Bernd (2004), "Tropical convexity", Documenta Mathematica 9: 1–27.

- Dress, Andreas W. M. (1984), "Trees, tight extensions of metric spaces, and the cohomological dimension of certain groups", Advances in Mathematics 53 (3): 321–402, doi:10.1016/0001-8708(84)90029-X.

- Dress, Andreas W. M.; Huber, K. T.; Moulton, V. (2001), "Metric spaces in pure and applied mathematics", Documenta Mathematica (Proceedings Quadratic Forms LSU): 121–139.

- Holsztyński, Włodzimierz (1968), "Linearisation of isometric embeddings of Banach Spaces. Metric Envelopes.", Bull. Acad. Polon. Sci. 16: 189–193.

- Isbell, J. R. (1964), "Six theorems about injective metric spaces", Comment. Math. Helv. 39: 65–76, doi:10.1007/BF02566944.

- Sturmfels, Bernd; Yu, Josephine (2004), "Classification of Six-Point Metrics", The Electronic Journal of Combinatorics 11: R44, arXiv:math.MG/0403147, Bibcode:2004math......3147S.

See also

- Kuratowski embedding, an embedding of any metric space into a Banach space defined similarly to the tight span

External links

- Joswig, Michael, Tight spans.