Tidal tensor

In Newton's theory of gravitation and in various relativistic classical theories of gravitation, such as general relativity, the tidal tensor represents

- tidal accelerations of a cloud of (electrically neutral, nonspinning) test particles,

- tidal stresses in a small object immersed in an ambient gravitational field.

Newton's theory

In the field theoretic elaboration of Newtonian gravity, the central quantity is the gravitational potential  , which obeys the Poisson equation

, which obeys the Poisson equation

where  is the mass density of any matter present. Note that this equation implies that in a vacuum solution, the potential is simply a harmonic function.

is the mass density of any matter present. Note that this equation implies that in a vacuum solution, the potential is simply a harmonic function.

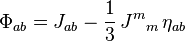

The tidal tensor is given by the traceless part

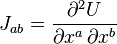

of the Hessian

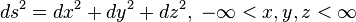

where we are using the standard Cartesian chart for E3, with the Euclidean metric tensor

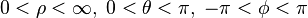

Using standard results in vector calculus, this is readily converted to expressions valid in other coordinate charts, such as the polar spherical chart

Spherically symmetric field

As an example, we compute the tidal tensor for the vacuum field outside an isolated spherically symmetric massive object in two different ways.

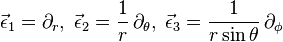

Let us adopt the frame obtained from the polar spherical chart for our three-dimensional Euclidean space:

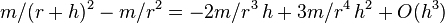

We will directly compute the tidal tensor, expressed in this frame, by elementary means, as follows. First, compare the gravitational forces on two nearby observers lying on the same radial line:

Because in discussing tensors we are dealing with multilinear algebra, we retain only first order terms, so  . Similarly, we can compare the gravitational force on two nearby observers lying on the same sphere

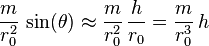

. Similarly, we can compare the gravitational force on two nearby observers lying on the same sphere  . Using some elementary trigonometry and the small angle approximation, we find that the force vectors differ by a vector tangent to the sphere which has magnitude

. Using some elementary trigonometry and the small angle approximation, we find that the force vectors differ by a vector tangent to the sphere which has magnitude

By using the small angle approximation, we have ignored all terms of order  , so the tangential components are

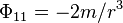

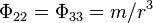

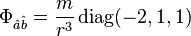

, so the tangential components are  . Combining this information, we find that the tidal tensor is diagonal with frame components

. Combining this information, we find that the tidal tensor is diagonal with frame components

This is the Coulomb form characteristic of spherically symmetric central force fields in Newtonian physics.

This is the Coulomb form characteristic of spherically symmetric central force fields in Newtonian physics.

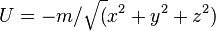

Next, let us plug the gravitational potential  into the Hessian. We can convert the expression above to one valid in polar spherical coordinates, or we can convert the potential to Cartesian coordinates before plugging in. Adopting the second course, we have

into the Hessian. We can convert the expression above to one valid in polar spherical coordinates, or we can convert the potential to Cartesian coordinates before plugging in. Adopting the second course, we have  , which gives

, which gives

After a rotation of our frame, which is adapted to the polar spherical coordinates, this expression agrees with our previous result. (The easiest way to see this is probably to set y,z to zero so that the off-diagonal terms vanish and  , and then invoke the spherical symmetry.)

, and then invoke the spherical symmetry.)

General relativity

In general relativity, the tidal tensor is identified with the electrogravitic tensor, which is one piece of the Bel decomposition of the Riemann tensor.

![\Phi_{ab} = \frac{m}{(x^2+y^2+z^2)^{5/2}} \, \left[ \begin{matrix} y^2+z^2-2x^2 & -3xy & -3xz \\ -3xy & x^2+z^2-2y^2 & -3yz \\ -3xz & -3yz & x^2+y^2-2z^2 \end{matrix} \right]](../I/m/97592f83cddee073a3e013c20cc7fb41.png)