Ticagrelor

| |

| |

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

|---|---|

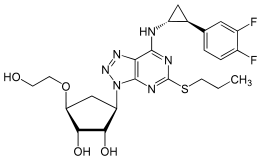

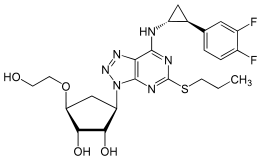

| (1S,2S,3R,5S)-3-[7-[(1R,2S)-2-(3,4-Difluorophenyl)cyclopropylamino]-5-(propylthio)- 3H-[1,2,3]triazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-3-yl]-5-(2-hydroxyethoxy)cyclopentane-1,2-diol | |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Brilinta, Brilique, Possia |

| MedlinePlus | a611050 |

| Licence data | EMA:Link, US FDA:link |

| |

| |

| Oral | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 36% |

| Protein binding | >99.7% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP3A4) |

| Half-life | 7 hrs (ticagrelor), 8.5 hrs (active metabolite AR-C124910XX) |

| Excretion | Biliary |

| Identifiers | |

|

274693-27-5 | |

| B01AC24 | |

| PubChem | CID 9871419 |

| ChemSpider |

8047109 |

| UNII |

GLH0314RVC |

| KEGG |

D09017 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL398435 |

| Synonyms | AZD-6140 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C23H28F2N6O4S |

| 522.567 g/mol | |

|

SMILES

| |

| |

| | |

Ticagrelor (trade name Brilinta in the US and Russia, Brilique and Possia in the EU) is a platelet aggregation inhibitor produced by AstraZeneca. The drug was approved for use in the European Union by the European Commission on December 3, 2010.[1][2] The drug was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration on July 20, 2011.[3]

Ticagrelor is an antagonist of the P2Y12 receptor.[4]

Medical uses

Ticagrelor is indicated for the prevention of thrombotic events (for example stroke or heart attack) in people with acute coronary syndrome or myocardial infarction with ST elevation. The drug is combined with acetylsalicylic acid unless the latter is contraindicated.[5]

There is no high quality evidence for the use of ticagrelor in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome.[6]

Contraindications

Contraindications for ticagrelor are: active pathological bleeding and a history of intracranial bleeding, as well as reduced liver function and combination with drugs that strongly influence activity of the liver enzyme CYP3A4, because the drug is metabolized via CYP3A4 and excreted via the liver.[5]

Adverse effects

The most common side effects are shortness of breath (dyspnea, 14%)[7] and various types of bleeding, such as hematoma, nosebleed, gastrointestinal, subcutaneous or dermal bleeding. Ventricular pauses of 3 seconds occur in 5 percent of people in the first week of treatment.Ticagrelor should be administered with caution or avoided in patients with advanced sinoauricular disease.[8] Allergic skin reactions such as rash and itching have been observed in less than 1% of patients.[5]

Interactions

Inhibitors of the liver enzyme CYP3A4, such as ketoconazole and possibly grapefruit juice, increase blood plasma levels and consequently can lead to bleeding and other adverse effects. Conversely, drugs that are metabolized by CYP3A4, for example simvastatin, show increased plasma levels and more side effects if combined with ticagrelor. CYP3A4 inductors, for example rifampicin and possibly St. John's wort, can reduce the effectiveness of ticagrelor. There is no evidence for interactions via CYP2C9.

The drug also inhibits P-glycoprotein (P-gp), leading to increased plasma levels of digoxin, ciclosporin and other P-gp substrates. Ticagrelor and AR-C124910XX levels are not significantly influenced by P-gp inhibitors.[5]

In the US a boxed warning states that use of ticagrelor with aspirin doses exceeding 100 mg/day decreases the effectiveness of the medication.[9]

Physical and chemical properties

Ticagrelor is a nucleoside analogue: the cyclopentane ring is similar to the sugar ribose, and the nitrogen rich aromatic ring system resembles the nucleobase purine, giving the molecule an overall similarity to adenosine. The substance has low solubility and low permeability under the Biopharmaceutics Classification System.[1]

Ticagrelor as a nucleoside analogue |

The nucleoside adenosine for comparison |

Pharmacokinetics

Ticagrelor is absorbed quickly from the gut, the bioavailability being 36%, and reaches its peak concentration after about 1.5 hours. The main metabolite, AR-C124910XX, is formed quickly via CYP3A4 by de-hydroxyethylation at position 5 of the cyclopentane ring.[10] It peaks after about 2.5 hours. Both ticagrelor and AR-C124910XX are bound to plasma proteins (>99.7%), and both are pharmacologically active. Blood plasma concentrations are linearly dependent on the dose up to 1260 mg (the sevenfold daily dose). The metabolite reaches 30–40% of ticagrelor's plasma concentrations. Drug and metabolite are mainly excreted via bile and feces.

Plasma concentrations of ticagrelor are slightly increased (12–23%) in elderly patients, women, patients of Asian ethnicity, and patients with mild hepatic impairment. They are decreased in patients that described themselves as 'coloured' and such with severe renal impairment. These differences are considered clinically irrelevant. In Japanese people, concentrations are 40% higher than in Caucasians, or 20% after body weight correction. The drug has not been tested in patients with severe hepatic impairment.[5]

Mechanism of action

Like the thienopyridines prasugrel, clopidogrel and ticlopidine, ticagrelor blocks adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptors of subtype P2Y12. In contrast to the other antiplatelet drugs, ticagrelor has a binding site different from ADP, making it an allosteric antagonist, and the blockage is reversible.[11] Moreover, the drug does not need hepatic activation, which might work better for patients with genetic variants regarding the enzyme CYP2C19 (although it is not certain whether clopidogrel is significantly influenced by such variants).[12][13][14]

Comparison with clopidogrel

The PLATO trial[15] found that ticagrelor had better mortality rates than clopidogrel (9.8% vs. 11.7%, p<0.001) in treating patients with acute coronary syndrome. Patients given ticagrelor were less likely to die from vascular causes, heart attack, or stroke but had greater chances of non-lethal bleeding (16.1% vs. 14.6%, p=0.0084) and higher rate of major bleeding not related to coronary-artery bypass grafting (4.5% vs. 3.8%, p=0.03). While the patient group on ticagrelor had more instances of fatal intracranial bleeding, there were significantly fewer cases of fatal non-intracranial bleeding, leading to an overall neutral effect on fatal or life-threatening bleeding vs. clopidogrel (p=0.70). Rates of major bleeding were not different. Discontinuation of the study drug due to adverse events occurred more frequently with ticagrelor than with clopidogrel (in 7.4% of patients vs. 6.0%, p<0.001).[16]

The PLATO trial showed a statistically insignificant trend toward worse outcomes with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel among US patients in the study – who comprised 1800 of the total 18,624 patients. The HR actually reversed for the composite end point cardiovascular (death, MI, or stroke): 12.6% for patients given ticagrelor and 10.1% for patients given clopidogrel (HR = 1.27). Some believe the results could be due to differences in aspirin maintenance doses, which are higher in the United States.[17] Others state that the central adjudicating committees found an extra 45 MIs in the clopidogrel (comparator) arm but none in the ticagrelor arm, which improved the MI outcomes with ticagrelor. Without this adjudication the trials' primary efficacy outcomes should not be significant.[18]

Consistently with its reversible mode of action, ticagrelor is known to act faster and shorter than clopidogrel.[19] This means it has to be taken twice instead of once a day which is a disadvantage in respect of compliance, but its effects are more quickly reversible which can be useful before surgery or if side effects occur.[5][20]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Assessment Report for Brilique" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. January 2011.

- ↑ European Public Assessment Report Possia

- ↑ "FDA approves blood-thinning drug Brilinta to treat acute coronary syndromes". FDA. 20 July 2011.

- ↑ Jacobson, Kenneth A.; Boeynaems, Jean-Marie (July 2010). "P2Y nucleotide receptors: promise of therapeutic applications". Drug Discovery Today 15 (13-14): 570–578. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2010.05.011.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Haberfeld, H, ed. (2010). Austria-Codex (in German) (2010/2011 ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag.

- ↑ Bellemain-Appaix, A.; Kerneis, M.; O'Connor, S. A.; Silvain, J.; Cucherat, M.; Beygui, F.; Barthelemy, O.; Collet, J.-P.; Jacq, L.; Bernasconi, F.; Montalescot, G. (24 October 2014). "Reappraisal of thienopyridine pretreatment in patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ 347 (aug06 2): g6269–g6269. doi:10.1136/bmj.g6269.

- ↑ Brilinta: Highlights of prescribing information

- ↑ 6

- ↑ Husten L (July 20, 2011). "AstraZeneca: Ticagrelor (Brilinta) Gains FDA Approval ?". CardioBrief. Blog at WordPress.com.

- ↑ Teng R, Oliver S, Hayes MA, Butler K (September 2010). "Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of ticagrelor in healthy subjects". Drug Metab. Dispos. 38 (9): 1514–21. doi:10.1124/dmd.110.032250. PMID 20551239.

- ↑ Birkeland K, Parra D, Rosenstein R (2010). "Antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndromes: focus on ticagrelor". J Blood Med 1: 197–219. doi:10.2147/JBM.S9650. PMC 3262315. PMID 22282698.

- ↑ Spreitzer H (February 4, 2008). "Neue Wirkstoffe - AZD6140". Österreichische Apothekerzeitung (in German) (3/2008): 135.

- ↑ Owen RT, Serradell N, Bolos J (2007). "AZD6140". Drugs of the Future 32 (10): 845–853. doi:10.1358/dof.2007.032.10.1133832.

- ↑ Tantry US, Bliden KP, Wei C, Storey RF, Armstrong M, Butler K, Gurbel PA (December 2010). "First analysis of the relation between CYP2C19 genotype and pharmacodynamics in patients treated with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel: the ONSET/OFFSET and RESPOND genotype studies". Circ Cardiovasc Genet 3 (6): 556–66. doi:10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.958561. PMID 21079055.

- ↑ Cannon CP, Harrington RA, James S, Ardissino D, Becker RC, Emanuelsson H, Husted S, Katus H, Keltai M, Khurmi NS, Kontny F, Lewis BS, Steg PG, Storey RF, Wojdyla D, Wallentin L (January 2010). "Comparison of ticagrelor with clopidogrel in patients with a planned invasive strategy for acute coronary syndromes (PLATO): a randomised double-blind study". Lancet 375 (9711): 283–93. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62191-7. PMID 20079528.

- ↑ Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H, Held C, Horrow J, Husted S, James S, Katus H, Mahaffey KW, Scirica BM, Skene A, Steg PG, Storey RF, Harrington RA, Freij A, Thorsén M (September 2009). "Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes". N. Engl. J. Med. 361 (11): 1045–57. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0904327. PMID 19717846.

- ↑ Lombo B, Díez JG (2011). "Ticagrelor: the evidence for its clinical potential as an oral antiplatelet treatment for the reduction of major adverse cardiac events in patients with acute coronary syndromes". Core Evid 6: 31–42. doi:10.2147/CE.S9510. PMC 3065559. PMID 21468241.

- ↑ Serebruany VL, Atar D (September 2012). "Viewpoint: Central adjudication of myocardial infarction in outcome-driven clinical trials--common patterns in TRITON, RECORD, and PLATO?". Thromb. Haemost. 108 (3): 412–4. doi:10.1160/TH12-04-0251. PMID 22836596.

- ↑ Miller, R (24 February 2010). "Is there too much excitement for ticagrelor?". TheHeart.org.

- ↑ H. Spreitzer (17 January 2011). "Neue Wirkstoffe - Elinogrel". Österreichische Apothekerzeitung (in German) (2/2011): 10.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||