Tibeto-Kanauri languages

| Tibeto-Kanauri | |

|---|---|

| Bodic, Bodish–Himalayish | |

| Geographic distribution: | Nepal, Tibet, and neighboring areas |

| Linguistic classification: |

|

| Subdivisions: | |

| Glottolog: | bodi1256[1] |

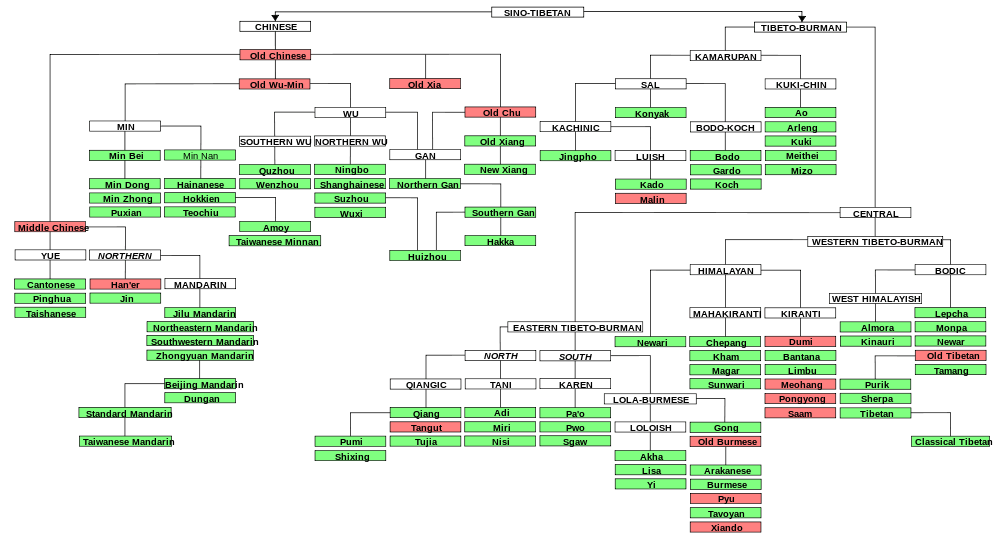

The Tibeto-Kanauri languages, also called Bodic, Bodish–Himalayish, and Western Tibeto-Burman, are a proposed intermediate level of classification of the Sino-Tibetan languages, centered on the Tibetic languages and the Kinnauri dialect cluster. The conception of the relationship, or if it is even a valid group, varies between researchers.

Conceptions of Tibeto-Kanauri

Western Tibeto-Burman languages, largely following Thurgood and La Polla (2003).[2]

Benedict (1972) originally posited the Tibeto-Kanauri aka Bodish–Himalayish relationship, but had a more expansive conception of Himalayish than generally found today, including Qiangic, Magaric, and Lepcha. Within Benedict's conception, Tibeto-Kanauri is one of seven linguistic nuclei, or centers of gravity along a spectrum, within Tibeto-Burman languages. The center-most nucleus identified by Benedict is the Jingpho language (including perhaps the Kachin–Luic and Tamangic languages); other peripheral nuclei besides Tibeto-Kanauri include the Kiranti languages (Bahing–Vayu and perhaps the Newar language); the Tani languages; the Bodo–Garo languages and perhaps the Konyak languages); the Kukish languages (Kuki–Naga plus perhaps the Karbi language, the Meithei language and the Mru language); and the Burmish languages (Lolo-Burmese languages, perhaps also the Nung language and Trung).[3]

Matisoff (1978, 2003) largely follows Benedict's scheme, stressing the teleological value of identifying related characteristics over mapping detailed family trees in the study of Tibeto-Burman and Sino-Tibetan languages. Matisoff includes Bodish and West Himalayish with the Lepcha language as a third branch. He unites these at a higher level with Mahakiranti as Himalayish.[4][5]

Van Driem (2001) notes that the Bodish, West Himalayish, and Tamangic languages (but not Benedict's other families) appear to have a common origin.[6]

Bradley (1997) takes much the same approach but words things differently: he incorporates West Himalayish and Tamangic as branches within his "Bodish", which thus becomes close to Tibeto-Kanauri. This and his Himalayan family constitute his Bodic family.[7]

References

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Bodic". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ Thurgood, Graham; LaPolla, Randy J. (ed.s) (2003). Sino-Tibetan Languages. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-7007-1129-5.

- ↑ Benedict, Paul K. (1972). Sino-Tibetan: a Conspectus. Princeton-Cambridge Studies in Chinese Linguistics 2. CUP Archive. pp. 4–11.

- ↑ Matisoff, James A. (1978). Variational semantics in Tibeto-Burman: The "Organic" Approach to Linguistic Comparison. Occasional papers, Wolfenden Society on Tibeto-Burman Linguistics 6. Institute for the Study of Human Issues. ISBN 0-915980-85-1.

- ↑ Matisoff, James A. (2003). Handbook of Proto-Tibeto-Burman: System and Philosophy of Sino-Tibetan Reconstruction. University of California Publications in Linguistics 135. University of California Press. pp. 1–9. ISBN 0-520-09843-9.

- ↑ van Driem, George (2001). Languages of the Himalayas: an Ethnolinguistic Handbook of the Greater Himalayan Region: Containing an Introduction to the Symbiotic Theory of Language. Handbuch der Orientalistik. Zweite Abteilung, Indien 10. Brill. ISBN 90-04-10390-2.

- ↑ Bradley, David (1997). Tibeto-Burman Languages of the Himalayas. Occasional Papers in South-East Asian linguistics (14). Dept. of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University. ISBN 0-85883-456-1.

Further reading

- Bradley, David (2002). "The subgrouping of Tibeto-Burman". In Christopher I. Beckwith. Medieval Tibeto-Burman languages: proceedings of a symposium held in Leiden, June 26, 2000, at the 9th Seminar of the International Association of Tibetan Studies. Brill's Tibetan studies library 1. BRILL. pp. 73–112. ISBN 978-90-04-12424-0.

- Hale, Austin (1982). "Review of Research". Research on Tibeto-Burman languages. Trends in Linguistics 14. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 30–49 passim. ISBN 978-90-279-3379-9.

- Singh, Rajendra (2009). Annual Review of South Asian Languages and Linguistics: 2009. Trends in Linguistics, Studies and Monographs 222. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 154–161. ISBN 978-3-11-022559-4.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||