Thrust

Thrust is a reaction force described quantitatively by Newton's second and third laws. When a system expels or accelerates mass in one direction, the accelerated mass will cause a force of equal magnitude but opposite direction on that system.[1] The force applied on a surface in a direction perpendicular or normal to the surface is called thrust. Force, and thus thrust, is measured in the International System of Units (SI) as the newton (symbol: N), and represents the amount needed to accelerate 1 kilogram of mass at the rate of 1 metre per second squared.

In mechanical engineering, force orthogonal to the main load (such as in parallel helical gears) is referred to as thrust.

Examples

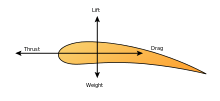

A fixed-wing aircraft generates forward thrust when air is pushed in the direction opposite to flight. This can be done in several ways including by the spinning blades of a propeller, or a rotating fan pushing air out from the back of a jet engine, or by ejecting hot gases from a rocket engine.[2] The forward thrust is proportional to the mass of the airstream multiplied by the difference in velocity of the airstream. Reverse thrust can be generated to aid braking after landing by reversing the pitch of variable-pitch propeller blades, or using a thrust reverser on a jet engine. Rotary wing aircraft and thrust vectoring V/STOL aircraft use engine thrust to support the weight of the aircraft, and vector sum of this thrust fore and aft to control forward speed.

Birds normally achieve thrust during flight by flapping their wings.

A motorboat generates thrust (or reverse thrust) when the propellers are turned to accelerate water backwards (or forwards). The resulting thrust pushes the boat in the opposite direction to the sum of the momentum change in the water flowing through the propeller.

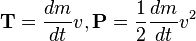

A rocket is propelled forward by a thrust force equal in magnitude, but opposite in direction, to the time-rate of momentum change of the exhaust gas accelerated from the combustion chamber through the rocket engine nozzle. This is the exhaust velocity with respect to the rocket, times the time-rate at which the mass is expelled, or in mathematical terms:

where T is the thrust generated (force),  is the rate of change of mass with respect to time (mass flow rate of exhaust), and v is the speed of the exhaust gases measured relative to the rocket.

is the rate of change of mass with respect to time (mass flow rate of exhaust), and v is the speed of the exhaust gases measured relative to the rocket.

For vertical launch of a rocket the initial thrust at liftoff must be more than the weight.

Each of the three Space Shuttle Main Engines could produce a thrust of 1.8 MN, and each of the Space Shuttle's two Solid Rocket Boosters 14.7 MN, together 29.4 MN. Compare with the mass at lift-off of 2,040,000 kg, hence a weight of 20 MN.

By contrast, the simplified Aid for EVA Rescue (SAFER) has 24 thrusters of 3.56 N each.

In the air-breathing category, the AMT-USA AT-180 jet engine developed for radio-controlled aircraft produce 90 N (20 lbf) of thrust.[3] The GE90-115B engine fitted on the Boeing 777-300ER, recognized by the Guinness Book of World Records as the "World's Most Powerful Commercial Jet Engine," has a thrust of 569 kN (127,900 lbf).

Thrust to power

The power needed to generate thrust and the force of the thrust can be related in a non-linear way. In general,  . The proportionality constant varies, and can be solved for a uniform flow:

. The proportionality constant varies, and can be solved for a uniform flow:

Note that these calculations are only valid for when the incoming air is accelerated from a standstill - for example when hovering.

The inverse of the proportionality constant, the "efficiency" of an otherwise-perfect thruster, is proportional to the area of the cross section of the propelled volume of fluid ( ) and the density of the fluid (

) and the density of the fluid ( ). This helps to explain why moving through water is easier and why aircraft have much larger propellers than watercraft do.

). This helps to explain why moving through water is easier and why aircraft have much larger propellers than watercraft do.

Thrust to propulsive power

A very common question is how to contrast the thrust rating of a jet engine with the power rating of a piston engine. Such comparison is difficult, as these quantities are not equivalent. A piston engine does not move the aircraft by itself (the propeller does that), so piston engines are usually rated by how much power they deliver to the propeller. Except for changes in temperature and air pressure, this quantity depends basically on the throttle setting.

A jet engine has no propeller, so the propulsive power of a jet engine is determined from its thrust as follows. Power is the force (F) it takes to move something over some distance (d) divided by the time (t) it takes to move that distance:[4]

In case of a rocket or a jet aircraft, the force is exactly the thrust produced by the engine. If the rocket or aircraft is moving at about a constant speed, then distance divided by time is just speed, so power is thrust times speed:[5]

This formula looks very surprising, but it is correct: the propulsive power (or power available [6]) of a jet engine increases with its speed. If the speed is zero, then the propulsive power is zero. If a jet aircraft is at full throttle but attached to a static test stand, then the jet engine produces no propulsive power, however thrust is still produced. Compare that to a piston engine. The combination piston engine–propeller also has a propulsive power with exactly the same formula, and it will also be zero at zero speed –- but that is for the engine–propeller set. The engine alone will continue to produce its rated power at a constant rate, whether the aircraft is moving or not.

Now, imagine the strong chain is broken, and the jet and the piston aircraft start to move. At low speeds:

The piston engine will have constant 100% power, and the propeller's thrust will vary with speed

The jet engine will have constant 100% thrust, and the engine's power will vary with speed

See also

- Aerodynamic force

- Astern propulsion

- Gimballed thrust, the most common thrust system in modern rockets

- Stream thrust averaging

- Thrust-to-weight ratio

- Thrust vectoring

- Tractive effort

References

- ↑ http://www.grc.nasa.gov/WWW/k-12/airplane/thrust1.html

- ↑ http://www.grc.nasa.gov/WWW/k-12/airplane/newton3.html

- ↑ "AMT-USA jet engine product information". Archived from the original on 2006-11-10. Retrieved 2006-12-13.

- ↑ "Convert Thrust to Horsepower By Joe Yoon". Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ "Introduction to Aircraft Flight Mechanics", Yechout & Morris

- ↑ "Understanding Flight", Anderson & Eberbaht