Thomas de Courtenay, 5th Earl of Devon

| Thomas Courtenay, 13th Earl of Devon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Spouse(s) | Margaret Beaufort |

|

Issue

Thomas Courtenay, 14th Earl of Devon Henry Courtenay Sir John Courtenay Joan Courtenay Elizabeth Courtenay Anne Courtenay Eleanor Courtenay Maud Courtenay | |

| Noble family | Courtenay |

| Father | Hugh Courtenay, 12th Earl of Devon |

| Mother | Anne Talbot |

Thomas Courtenay, 5th Earl of Devon (1414–1458) was an English nobleman who was involved in the Wars of the Roses. His seat was Colcombe Castle, near Colyton, Devon, and later the principal historic family seat of Tiverton Castle after his mother's death. Much of his life was spent in armed territorial struggle against his near-neighbour in Devon Sir William Bonville of Shute, Devon, at a time when central control over the provinces was weak. He had been married off as an infant to Margaret Beaufort, granddaughter of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, and started his career an adherent to the Lancastrian Beaufort party. On the demise of the Beaufort party he abandoned it in favour of the Duke of York. When York sought the support of Courtenay's arch-enemy Bonville, Courtenay fell out of favour with York. The Wars of the Roses led to the deaths and executions of all three of his sons, successively 6th, 7th, and 8th Earls of Devon, and the eventual attainder of his titles and forfeiture of his lands. The Earldom was however revived in 1485 for his distant cousin Sir Edward Courtenay, KG, (died 1509), third in descent from his great-uncle.

Youth

Courtenay was born in 1414, the only surviving son of Hugh Courtenay, 12th Earl of Devon (1389 – 16 June 1422), and Anne Talbot.[1] He inherited the earldom in 1422 at the age of eight.

On 1 May 1424, his late father's estates were delivered during his minority, in exchange for 700 marks per annum, into the wardship of the young Courtenay's uncle, John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury, and of his mother the Dowager Countess Anne (d. 1441) [2][3] along with a series of local gentlemen and lawyers.[4][5] His mother, the dowager countess, received the customary dower third, including the primary Courtenay residence at Tiverton Castle, while a group of the late earl’s intimates were enfeoffed with another considerable group of manors to satisfy his debts and the terms of his will.[6] It seems that their combined stewardship was far from satisfactory, as royal officials noted that his estates were ruinous and his deer parks so dilapidated that he was permitted as compensation to hunt in royal parks.[7] This may have been for his part in Sir Thomas Rempston's expedition into Normandy the previous winter where they garrisoned the town of St. James-de-Beuvron.[8]

According to Cokayne, Courtenay was knighted on 19 May 1426 by King Henry VI,[9] and on 16 December 1431 Courtenay was among an entourage of 300 who attended Henry VI's second coronation[10] at Notre Dame in Paris.[11]

Majority

Apparently aged just 19, thus two years early,[12] Courtenay was granted livery to enter his lands and obtain his inheritance on 20/1 February 1433, on the payment of a relief of 1000 marks.[13] It appears that no inquisition of proof of age, customary for a tenant in chief, was taken. Based on his family’s history and standing and on his own position as the leading landowner of the county, probably expected to take his place as the leader of Devon society. However, his mother’s longevity meant that her dower portion, including Tiverton Castle, and the other Courtenay estates which had been alienated under his father’s will were not in his hands and the young Courtenay was forced to live at Colcombe Castle, near Colyton, very close to his enemy William Bonville, 1st Baron Bonville, at Shute.[14] His income of £1500 p.a. was lower than that of most nobles of comparable rank.

Career

Struggle with Bonville

The new earl found the political situation in Devonshire increasingly stacked against his own interests as a coalition of the greater gentry, led by William Bonville, 1st Baron Bonville, and the earl’s cousin, Sir Philip Courtenay of Powderham, threatened the Courtenays’ traditional dominance of the county. The relationship was complicated by Bonville's second marriage in 1430 to Elizabeth Courtenay (d.1471), Courtenay's aunt. Despite links via his wife, Margaret Beaufort, to the ascendant "court party" led by Cardinal Beaufort and John Beaufort, 1st earl of Somerset and Marquess of Dorset, and by Margaret Holland, daughter of the Earl of Kent, Courtenay failed to rectify his situation and instead resorted to violence, beginning in 1439. With the decline of Beaufort power, Courtenay became increasingly associated with Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York. Courtenay had been attacking Bonville's estates in the summer of 1439 and the king despatched a Privy Councillor, Sir John Stourton, 1st Baron Stourton, to extract a promise of good behavior from Courtenay, who was thereafter reluctant to attend the court in London.[16][17] In 1441, Courtenay was appointed as Steward of the Duchy of Cornwall, a nearly identical post to Royal Steward for Cornwall which had been granted to Sir William Bonville in 1437, for life.[18] A week later in May 1441, the warrant was retracted. Disputes arose between the two which contemporary records portray as reaching the status of a private war. Two men wearing Courtenay livery attacked Sir Philip Chetwynd, a friend of Bonville, on the road to London. Apparent evidence that the Council's arbitration of November 1440 had failed.[19] Courtenay and Bonville were summoned before the King in December 1441, and were publicly reconciled.[20] Tensions remained however and this may have been a factor in the crown’s requests to both Courtenay, who initially refused, and Bonville to serve in France, Bonville as seneschal of Gascony from 1442-6 and Courtenay at Pont-l'Évêque in Normandy in 1446.[21] This is one of the few times that Courtenay served abroad, for he had refused in March 1443, seemingly preferring to spend his time bolstering his position in Devon or at court. While Bonville was abroad, the King released Devon from his debts, including the recognisance for good behaviour, probably remitted by the influence of father-in-law, John Beaufort, Earl of Somerset.[22]

Royal appointments

Commissions

His advantageous marriage to Margaret Beaufort brought him links to the "court party", and Courtenay began to be selected by the king to serve on Westcountry commissions and was granted an annuity of £100 for his services.[23]

Other

1445 marked a fleeting high point in Courtenay’s fortunes, with his appointment as High Steward of England at Queen Margaret’s coronation on 25 May.[24] Only the year before, March 1444, Bonville had identified himself with Suffolk, at Margaret's bethrothal in Rouen.

Abandonment of Beauforts

The deaths of his brother-in-law John Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset, in 1444, and of the leader of the party Cardinal Beaufort, 2nd son of John of Gaunt, in 1447, removed Beaufort leadership of the ‘court’ party, leaving William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk as the most influential figure in national politics [25] While there is no evidence of direct antagonism between Courtenay and the Duke of Suffolk, the latter appeared to favour the Bonvilles. Sir William Bonville enjoyed links with Suffolk and married his daughter to William Tailboys, one of the Duke's closest associates. Perhaps the most dramatic illustration of this favour was Bonville’s elevation to the peerage, presumably at the direction of Suffolk, as Baron Bonville of Chewton Mendip in 1449.[26]

Switch to Yorkist party

This promotion of his enemy Bonville may have prompted Devon to oppose the 'Court party' and to serve with his friend Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York during the Cade Rebellion. Courtenay switched allegiance to York, who with the Duke of Norfolk took control briefly of London. He remained loyal to York during the Parliament of November 1450, when they invoked the support of the Commons to raise taxation. Having rescued the Duke of Somerset from an angry London mob, York himself had to flee, taking refuge on the Earl of Devon's barge rowing down the Thames. It is hardly surprising that Devon began to become associated with York, who had assumed the leadership of the "opposition" party. The parlous state of national politics (whether the king was a vindictive factionalist or an inane non-entity is largely irrelevant in this context) combined with what seems like a reckless and violent element in Courtenay’s own character, led to a further campaign of violence against Bonville and the Suffolk-aligned James Butler, 5th Earl of Ormond and Earl of Wiltshire. Courtenay and his troops attempted to capture Butler near Bath in Wiltshire before returning to besiege Bonville in Taunton Castle. The arrival of York (whether to suppress or aid the disturbances is uncertain) caused the two sides to make peace which, unsurprisingly, had no real meaning.[27] York then embarked on his abortive attempt to take control of royal government by force, his only allies being Courtenay and his sometime-associate, Edward Brooke, 6th Baron Cobham.

In the West Country Courtenay hounded Bonville without mercy, and pursued him to Taunton Castle and laid siege to it.[28] York arrived to lift the siege, and imprisoned Bonville, who was nevertheless quickly released.

Defeat of Yorkists

York's and Courtenay's humiliation by Henry VI and Suffolk at the Dartford meeting in 1452, led to the confirmation of Bonville as Constable of Exeter Castle, making him the king's chief officer in Devon. This marked a low ebb in Courtenay's fortunes and represented the biggest threat to his position as the premier noble and landowner in the county.[29] This exploit ended with the disgrace of all three 'Yorkists' and their submission to royal mercy in March. The King had issued an arrest warrant on 24 September 1451, drafted by Somerset, to be enforced by Butler and Bonville. The Yorkist rebellions prompted royal commissions for Buckingham and Bonville on 14 February 1452. A direct summons without delay was ordered by Royal Proclamation on 17 February to bring Courtenay and Lord Cobham [30] to London. Two days later, demonstrations were held by Courtenay's army at Yeovil and Ilminster, converging with York's on London.[31]

Treason charge

Courtenay was charged with treason and briefly imprisoned in Wallingford Castle,[32] before appearing on trial before the House of Lords. His disgrace and political isolation allowed his Devonshire rivals to consolidate their positions, further undermining his decreased standing in the county.[33] Bonville acquired all royal commissions in the south-west.

Resurgence of York

King Henry VI's madness and York’s appointment as Protector in 1453/4 resulted in a partial rally in Courtenay’s fortunes, including his re-appointment to commissions of the peace in the south-western counties, the key barometer of the local balance of power.[34] He was a member of the Royal Council until April 1454.[35] Courtenay was bound over to keep the peace with a fine of 1000 marks, but ignored its restrictions. Threatened by the Council on 3 June, he was forced on 24 July to make a new bond.[36]

Abandonment by York

This was, however, the end of Courtenay’s links with York, whose increasingly tight links with the Neville earls of Salisbury and Warwick led to an alignment with Bonville away from Courtenay. This culminated in the marriage of William Bonville, 6th Baron Harington, Bonville’s grandson, to Salisbury’s daughter, Katherine. Courtenay did not endear himself to Somerset either, as he and his sons repeatedly disrupted the sessions of the commissioners of the peace in Exeter during 1454/5, which did not assist Protector Somerset in promoting his role as the guardian of law and order. Courtenay was present at the First Battle of St Albans, and was wounded.[37] York however still considered him at least neutral as the Duke’s letters addressed to the King on the eve of battle were delivered to the king via the apparently still trusted hands of Courtenay.[38]

Final assault on Bonville

Perhaps inspired by the way the Nevilles and York had forcefully ended their respective feuds with the Percies and the Duke of Somerset in the battle, Courtenay returned to Devon and commenced a further campaign of violence against Bonville and his allies, who were now attached to Warwick's party. The violence began in October 1455 with the horrific murder by Courtenay allies of Nicholas Radford, an eminent Westcountry lawyer,[39] Recorder of Exeter and one of Bonville’s councilors. Several contemporary accounts, including the Paston Letters, record this event with the ensuing mock-funeral and coronary inquest accompanied by the singing of highly inappropriate songs, in tones of shock and horror unusual during the blunted sensitivities of the fifteenth century.[40] Among the murderers was Thomas Courtenay, the earl’s son and later successor.[41] Parliament, meeting in November 1455, reported 800 horsemen and 4,000 infantry running amok across Devon. On 3 November 1455 Courtenay with his sons, Thomas Carrew of Ashwater and a considerable force of 1,000 men occupied the city of Exeter, nominally controlled by Bonville as castellan of the royal castle of Exeter, which they continued to control until 23 December 1455.[42] Courtenay had before warned the populace that Bonville was approaching with a 'great multitude' to sack the city. On 3 November 1455 Bonville's men setting out from his seat at Shute had looted the Earl's nearby house at Colcombe Castle, Colyton, and Bonville promised his support to the Earl's distant cousin, Sir Philip Courtenay of Powderham. Dozens of men violated consecrated ground and Radford’s valuables were extracted from the cathedral and his house in Exeter was also robbed. Village-dwellers with Bonville connections were assaulted by Devon's men. Powderham Castle, home to the earl’s estranged cousin, Sir Philip Courtenay (d.1463), an ally of Bonville, was besieged on 15 November 1455, the earl’s weaponry now including a serpentine cannon. Bonville attempted to relieve the castle but was repulsed as the Earl threatened to batter down its walls.[43] Finally battle was joined directly between Bonville and Courtenay at the Battle of Clyst Heath, at Clyst Bridge, just south east of Exeter on 15 December 1455. While it seems that Bonville was put to flight, the number of dead or wounded is entirely unknown. Two days later Thomas Carrew with 500 of Courtenay's retainers pillaged Shute, seizing a bounty of looted goods. Courtenay and his men left Exeter on 21 December 1455 and shortly afterwards submitted to York at Shaftesbury in Dorset. Early in December 1455 the King had dismissed Devon from the Commission of Peace, and citizens of Exeter had been instructed not to help his army of "misrule" in any way.[44]

Aftermath of Clyst Heath

Devon was incarcerated in the Tower. Originally, the government planned to bring him to trial for treason but this was abandoned once the King Henry VI returned to sanity in February 1456, and York was removed as Protector. Courtenay was also returned to the commission of the peace for Devonshire, seemingly the work of Queen Margaret of Anjou who had taken personal control of the court. Courtenay had cultivated links with Queen Margaret, and an alliance was sealed by the marriage of his son and heir, Sir Thomas Courtenay, to the Queen’s kinswoman, Marie, the daughter of Charles, Count of Maine. Despite having been banned from entering and leading armed men into Exeter and holding assemblies, 500 men under John Courtenay entered the High Street on 8 April 1456. His rivals, Philip Courtenay and Lord Fitzwarin, were prevented from exercising commissions as Justices of the Peace, and were forced to leave the city. Butler, Bonville's patron, and Sir John Fortescue, Chief Justice, arrived with a large entourage to investigate under a commission of oyer et terminer. They rejected Courtenay's petition to have Bonville's sheriffdom of Devon removed.[45] Two years later his sons, Thomas and Henry Courtenay, were absolved of the murder of Nicholas Radford.[46]

Courtenay was restored to the bench of JPs and was made Keeper of the Park of Clarendon in February 1457,[47] and Keeper of Clarendon Forest in Wiltshire on 17 July 1457.[48]

Marriage and issue

At some time after 1421 Courtenay married Lady Margaret Beaufort (c. 1409–1449), daughter of John Beaufort, 1st Marquess of Somerset, 1st Marquess of Dorset (1373-1410), KG, (later only 1st Earl of Somerset), (the first of the four illegitimate children of John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster (4th son of King Edward III), and his mistress Katherine Swynford, later his wife) by his wife Margaret Holland. Margaret was thus sister of Henry Beaufort, 2nd Earl of Somerset, of John Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset, of Thomas Beaufort, Count of Perche, of Joan Beaufort, Queen of Scotland and of Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset. They had three sons and five daughters:[50]

- Thomas Courtenay, 6th/14th Earl of Devon (1432 - 3 April 1461), who married, shortly after 9 September 1456, Mary of Anjou, illegitimate daughter of Charles, Count of Maine. There were no issue of the marriage. He was taken prisoner at the Battle of Towton, and beheaded at York on 3 April 1461, when the earldom was forfeited.[51]

- Henry Courtenay (d. 1467/9), Esquire, of West Coker, Somerset, beheaded for treason in the market place at Salisbury, Wiltshire on 17 January 1469 (or 4 March 1467[52]). As the earldom had been forfeited following the execution of his elder brother in 1461, he is not generally considered to have inherited from him the title Earl of Devon, although for example Debrett's Peerage, 1968 gives him as the 7th Earl and successor to his brother.[53]

- Sir John Courtenay, (1435-3 May 1471), slain at the Battle of Tewkesbury on 4 May 1471.[54]

- Joan Courtenay, (born c. 1447), who married firstly, Sir Roger Clifford, second son of Thomas Clifford, 8th Baron de Clifford, beheaded after Bosworth in 1485. She married secondly, Sir William Knyvet of Buckenham, Norfolk.[55]

- Elizabeth Courtenay (born c. 1449), who married, before March 1490, Sir Hugh Conway.[56]

- Anne Courtenay.

- Eleanor Courtenay.

- Maud Courtenay.

Monument to Margaret Beaufort

An effigy identified by tradition as "little choke-a-bone", Margaret Courtenay (d. 1512), an infant daughter of William Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (1475-1511) by his wife Princess Catherine of York (d.1527), the sixth daughter of King Edward IV (1461-1483)[57] exists in Colyton Church in Devon. The Courtenay residence of Colcombe Castle was in the parish of Colyton. However, modern authorities [58] have suggested, on the basis of the monument's heraldry, the effigy to be Margaret Beaufort (c. 1409–1449), the wife of Thomas de Courtenay, 5th Earl of Devon (1414–1458).

The effigy is only about 3 ft in length, much smaller than usual for an adult. The face and head was renewed in 1907,[59] and is said to have been based on the sculptor's own infant daughter. A 19th century brass tablet above is inscribed: "Margaret, daughter of William Courtenay Earl of Devon and the Princess Katharine youngest daughter of Edward IVth King of England, died at Colcombe choked by a fish-bone AD MDXII and was buried under the window in the north transept of this church".

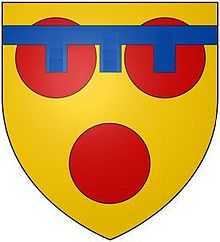

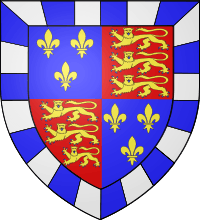

Heraldry

Three sculpted heraldic shields of arms exist above the effigy, showing the arms of Courtenay, Courtenay impaling the royal arms of England and the royal arms of England. Later authorities[62] have suggested, on the basis of the monument's heraldry, the effigy to be the wife of Thomas de Courtenay, 5th Earl of Devon (1414–1458), namely Lady Margaret Beaufort (c. 1409–1449), daughter of John Beaufort, 1st Marquess of Somerset, 1st Marquess of Dorset (1373-1410), KG, (later only 1st Earl of Somerset), (the first of the four illegitimate children of John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster (4th son of King Edward III), and his mistress Katherine Swynford, later his wife) by his wife Margaret Holland. The basis of this re-attribution is the supposed fact that the "royal arms" shown are not the arms of King Edward IV, but rather the arms of Beaufort. The arms of Beaufort are the royal arms of England differenced within a bordure compony argent and azure. [63] The relief sculpture does indeed show a border, albeit a thin one and not compony, around the royal arms, with such border omitted from the Courtenay arms.

Death

Courtenay received a summons to appear with York before the King in London at the Loveday Award. He broke his journey at Abingdon Abbey, and died there on 3 February 1458.[64] A contemporary chronicler asserted that he had been poisoned by the Prior on the Queen's orders, which is perhaps unlikely considering the Earl's alliance with the Queen. In his will the Earl requested burial in the Courtenay Chantry Chapel of Exeter Cathedral. The will was proved at Lambeth on 21 February 1458, and an inquisition post mortem was taken in 1467.[65]

The Earl was succeeded by his eldest son, Thomas Courtenay, 14th Earl of Devon,[66] who was beheaded at York on 3 April 1461 after the Battle of Towton, and attainted by Parliament in November 1461, whereby the earldom was forfeited.[67]

Footnotes

- ↑ Cokayne 1916, p. 326.

- ↑ CPR, 1429-36, 271

- ↑ Calendar of Fine Rolls 1422-29. pp. 58, 62–3, 77–8.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls 1416-22. p. 439. Calendar of Patent Rolls 1422-29. pp. 18, 46.

- ↑ He may at some time before have become a ward of the all-powerful Duke of Exeter.(Griffiths, R.A, "Reign of Henry VI", (2004), 15)

- ↑ Calendar of Close Rolls 1422-29. pp. 6, 39.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls 1429-36. p. 271,464.

- ↑ The Chronicler de Beaucourt remarked that the French were routed by an enemy twenty times its inferior in numbers. It became known as the route of St James. The unexpected victory, led Jean V, the King of France to submit to Henry VI at Paris the following summer, after Suffolk had led a campaign to capture Rennes and overrun Brittany.(A. H. Burne, The Hundred Years War, pp. 373-74.) Meanwhile the Earl of Suffolk held the bishopric town of Avranches.(Sir Harris Nicholas ed. Proceedings and Ordinances of the Privy Council v.4. p. 30.

- ↑ Cokayne 1916, p. 326.

- ↑ Griffiths 2004.

- ↑ Griffiths, 15

- ↑ He was apparently aged only 19 whilst the usual age of majority for a male was 21

- ↑ CPR, 1429-36, 271

- ↑ Martin Cherry (1981). The Crown and the Political Community in Devonshire. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Wales, Swansea.

- ↑ Source: Burke's General Armory 1884, p.99

- ↑ CPR, op cit., 314, 448.

- ↑ The pirate-soldier, Sir Hugh Courtenay, a cousin looted merchant vessels along the coast, and led brigands with Thomas Carminow, after a long dispute with the Earl

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls 1436-41. p. 133,532.

- ↑ the "Arbitration" was published on 1 April 1442.

- ↑ PPC v.5. pp. 165–6, 173–5.

- ↑ PPC v5. p. 240.

- ↑ PPC, V, 408; Calendar of Close Rolls, 1435-1441, 396.

- ↑ PPC v.6. p. 315.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls 1441-46. p. 355.

- ↑ Watts, J.L, Henry VI and the Politics of Kingship (Cambridge, 1996)and R.L. Griffiths, The reign of King Henry VI (Stroud, 1998) for differing views on the relationship between Suffolk and Henry VI).

- ↑ Calendar of Close Rolls 1447-54. p. 107.

- ↑ Martin Cherry (1981). The Crown and the Political Community in Devonshire. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Wales, Swansea. p. 281.

- ↑ Storey 1999, p. 84.

- ↑ Storey 1999, p. 94.

- ↑ Lord Cobham had been dispossessed by the Earl of Wiltshire, a creation of Henry VI.ibid, 98

- ↑ Rotuli Parliamentorum, V, 248-9

- ↑ Hariss, G.L, "A Fifteenth century chronicle at Trinity College, Dublin", British Institute of Historical Research, XXXVIII (1965), 216

- ↑ Martin Cherry (1981). The Crown and the Political Community in Devonshire. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Wales, Swansea. pp. 285–6.

- ↑ Martin Cherry (1981). The Crown and the Political Community in Devonshire. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Wales, Swansea. p. 290.

- ↑ Storey 1999, p. 165; Proceedings and Ordinances of the Privy Council of England. VI, 189-193

- ↑ Storey 1999, p. 166.

- ↑ Storey 1999, p. 166.

- ↑ Martin Cherry (1981). The Crown and the Political Community in Devonshire. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Wales, Swansea. p. 297.

- ↑ "apprentice of the law" Radford was a well-known local dignitary, an old man at the time; Calendar of the Patent Rolls, 1446-1452, pp.269, 281

- ↑ J.D. Gairdner ed. (1897). The Paston Letters v.1. p. 351.

- ↑ Storey 1999, pp. 168–70.

- ↑ Storey 1999, p. 167; Estates of the Percy family, 89-96

- ↑ Martin Cherry (1981). The Crown and the Political Community in Devonshire. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Wales, Swansea. p. 311.

- ↑ Storey 1999, p. 173.

- ↑ Rotuli, op cit., 332

- ↑ CPR 1452-61, 308, 393, 398

- ↑ History of Commons, 1422-1508, vol. II

- ↑ Cokayne 1916, p. 326.

- ↑ Debrett's Peerage, 1968, p. 125

- ↑ Richardson IV 2011, pp. 38–43.

- ↑ Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitation of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620, Exeter, 1895, p.245

- ↑ Vivian, p.245

- ↑ Montague-Smith, P.W. (ed.), Debrett's Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Companionage, Kelly's Directories Ltd, Kingston-upon-Thames, 1968, p.353, incorrectly named as "Hugh, attainted and beheaded 1466"

- ↑ Cokayne, p. 327

- ↑ Cokayne 1916, p. 327.

- ↑ Cokayne 1916, p. 327.

- ↑ Vivian, Lt.Col. J. L., (ed.) The Visitation of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620, Exeter, 1895, p. 245

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th edition, 1911, "Courtenay"; Pevsner, Nikolaus & Cherry, Bridget, The Buildings of England: Devon, London, 2004, p.280; Hoskins, W. G., A New Survey of England: Devon, London, 1959 (first published 1954), p. 373

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th edition, 1911, "Courtenay"

- ↑ raised horizontal line on top of shield is part of the label, a differencing charge shown in the Courtenay arms

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th edition, 1911, "Courtenay"

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th edition, 1911, "Courtenay"; Pevsner, Nikolaus & Cherry, Bridget, The Buildings of England: Devon, London, 2004, p.280; Hoskins, W. G., A New Survey of England: Devon, London, 1959 (first published 1954), p. 373

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th edition, 1911, "Courtenay": The effigy of this grandaughter of John of Gaunt, with the shields of Courtenay and Beaufort (sic) above it, is in Colyton church. It is less than life size, a fact which has given rise to a village legend that it represents “Little choke-a-bone,” an infant daughter of the tenth earl, who died “choked by a fish bone.” In spite of the evidence of the shields and the 15th century dress of the effigy, the legend has now been strengthened by an inscription upon a brass plate, and in the year 1907 ignorance engaged a monumental sculptor to deface the effigy by giving its broken features the newly carved face of a young child.

- ↑ Cokayne 1916, p. 327; Richardson IV 2011, p. 40.

- ↑ Cokayne 1916, p. 327.

- ↑ Richardson I 2011, p. 547.

- ↑ Cokayne 1916, p. 327; Richardson IV 2011, p. 40.

References

- Cokayne, George Edward (1916). The Complete Peerage, edited by Vicary Gibbs IV. London: St. Catherine Press.

- Griffiths, R.A. (2004). Henry VI (1421–1471). Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 26 October 2012. (subscription required)

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, ed. Kimball G. Everingham I (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. ISBN 1449966373

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, ed. Kimball G. Everingham IV (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. ISBN 1460992709

- Storey, R.L. (1999). The End of the House of Lancaster (2nd rev ed.). Sutton.

Selected reading

- Bellamy, J. G., The Law of Treason in England in the Later Middle Ages (Cambridge, 1970).

- Bellamy, J. G., Crime and Public Order in England in the Later Middle Ages (1973).

- Carpenter, Christine Wars of the Roses: Politics and Constitution in England, 1437-1509, (CUP, 1997).

- Cherry, M. 'The Courtenay earls of Devon: the formation and disintegration of a late medieval aristocratic affinity', Southern History; 1 (1979), 71-97.

- Cherry, M., 'The Struggle for power in Mid-fifteenth century Devonshire', cited in Griffiths, Patronage, 123-44.

- Griffiths, R. A. The Reign of Henry VI, (Sutton, 1998).

- Griffiths, R. A., "The King's Council and the First Protectorate of the Duke of York, 1453-1454", EHR, 99 (1984), 67-81.

- Griffiths, R. A., 'Duke Richard of York's intentions in 1450 and the origin of the Wars of the Roses', Journal of Medieval History, 1 (1975), 187-209.

- Griffiths, R. A., ed. 'Patronage, The Crown and the Provinces in Later Medieval England', (Gloucester, 1981).

- Jacob, E. F., 'The Fifteenth Century, 1399-1485', Oxford History of England, (Clarendon Press, reprint 1988)

- Kleineke, Hannes 'The Kynges Cite: Exeter in the Wars of the Roses' in L. Clark ed., The Fifteenth Century VII: Conflicts, Consequences and the Crown in the Late Middle Ages (Woodbridge, 2007).

- McFarlane, K. B. The Nobility of Later Medieval England (OUP, 1973).

- Myers, A. E, ed., English Historical Documents 1327-1485 (1969)

- Ross, Charles, The Wars of the Roses, (Thames and Hudson, 1986).

- Seward, Desmond, The Wars of the Roses; and the lives of five men and women in the fifteenth century. London: Constable, 1995

- Sumption, Jonathan The Hundred Years War, 2 vols., vol.I: Trial by Battle, vol.II: Trial by Fire (Faber, 1999).

- Tuck, Anthony Crown and Nobility: England 1272-1461: political conflict in late medieval England 2nd ed. (Blackwell, 1999).

- Virgoe, R., 'The Composition of the King's Council', BIHR, 43 (1970), 134-60.

- Watts, J. L. Henry VI and the Politics of Kingship (Cambridge, 1996).

| Preceded by Hugh de Courtenay |

Earl of Devon 1422–1458 |

Succeeded by Thomas Courtenay |