Thiess of Kaltenbrun

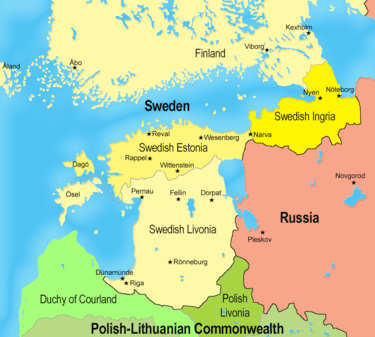

Thiess of Kaltenbrun, also spelled Thies, and commonly referred to as the Livonian werewolf, was a Livonian man who was put on trial for heresy in Jürgensburg, Swedish Livonia, in 1692. At the time in his eighties, Thiess openly proclaimed himself to be a werewolf (wahrwolff), claiming that he ventured into Hell with other werewolves in order to do battle with the Devil and his witches. Although claiming that as a werewolf he was a "hound of God", the judges deemed him guilty of trying to turn people away from Christianity, and he was sentenced to be both flogged and banished for life.

According to Thiess' account, he and the other werewolves transformed into wolf form on three nights a year, and then traveled down to Hell. Once there, they fought with the Devil and his witches in order to rescue the grain and livestock which the witches had stolen from the Earth.

Various historians have turned their attention towards the case of Thiess, interpreting his werewolf beliefs in a variety of different ways. In his book The Night Battles (1966), the Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg compared Thiess' practices to those of the benandanti of northeastern Italy, and argued that they represented a survival of pre-Christian shamanic beliefs. Ginzburg's ideas were later critiqued by the Dutch historian Willem de Blécourt.

Thiess' trial

Origins

In 1691, the judges of Jürgensburg, a town in Swedish Livonia, brought before them an octogenarian known as Thiess of Kaltenbrun, believing him to be a witness in a case regarding a church robbery. They were aware of the fact that local people considered him to be a werewolf who had consorted with the Devil, but they initially had little interest in such allegations, which were unrelated to the case at hand.[1] Nonetheless, although it had no bearing on the case, Thiess freely admitted to the judges that he had once been a werewolf, but claimed to have given it up ten years previously.[1][2] Thiess proceeded to offer them an account of lycanthropy that differed significantly from the traditional view of the werewolf then prevalent in northern Germany and the Baltic countries.[2]

Thiess told the judges of how ten years previously, in 1681, he had also appeared in court, when he had accused a farmer from Lemburg of breaking his nose. According to the story that he had then told, he had traveled down to Hell as a wolf, where the farmer, who was a practicing Satanic witch, had beat him on the nose with a broomstick decorated with horses' tails. At the time, the judges had refused to believe his story, and had laughed him out of court, but one of the judges did verify that his nose had indeed been broken.[1]

This time, the judges of Jürgensburg decided to take his claims more seriously, and trying to establish if he was mad or sane, they asked several individuals in the court who knew Thiess if he was of sound mind. They related that as far as they knew, his common sense had never failed him.[1] These individuals also related that Thiess' status in the local community had actually increased since his run in with the law back in 1681.[1]

Thiess' account

"Ordinarily, [they went to Hell] three times: during the night of Pentecost, on Midsummer's Night, and on St Lucia's Night; as far as the first two nights were concerned, they did not go exactly during those nights, but more when the grain was properly blooming, because it is at the time the seeds are forming that the sorcerers spirit away the blessing and take it to hell, and it is then that the werewolves take it upon themselves to bring it back out again."

Thiess claimed that on the night of St. Lucia's Day, and usually also on the nights of Pentecost and St. John's Day, he and the other werewolves transformed from their human bodies into wolves.[2][3][4] When questioned further on how this occurred, Thiess initially claimed that they did so by putting on wolves' pelts, claiming that he had originally obtained his from a farmer, but that several years before he had passed it on to someone else. When the judges asked him to identify these individuals, he changed his story, claiming that he and the other werewolves simply went into the bushes, undressed and then transformed into wolves.[1] Following this, Thiess related that he and the other werewolves wandered around local farms and ripped apart any farm animals that they came across before roasting the meat and devouring it. When the judges enquired how wolves could roast meat, Thiess told them that at this point, they were still in human form, and that they liked to add salt to their food, but never had any bread.[4]

Thiess also told the judges of how he had first become a werewolf, explaining that he had once been a beggar, and that one day "a rascal" had drunk a toast to him, thereby giving him the ability to transform into a wolf. He furthermore related that he could pass on his ability to someone else by toasting them, breathing into the jug three times and proclaiming "you will become like me." If the other individual then took the jug, they would become a werewolf, but Thiess claimed that he was yet to find anyone ready to take over the role of lycanthrope from him.[4]

This done, Thiess related that the wolves travelled to a place that was located "beyond the sea".[2] This spot was a swamp near Lemburg, about half a mile away from the estate of the court's chairman.[1][3] Here they entered into Hell, where they battled both the Devil and the malevolent witches who were loyal to him, beating them with long iron rods and chasing them like dogs.[2] Thiess furthermore told the judges that the werewolves "cannot tolerate the devil",[2] and that they were the "hounds of God".

The judges of Jürgensburg were confused, asking Thiess why the werewolves traveled to Hell if they hated the Devil. He responded by telling them that he and his brethren had to go on their journey in order to bring back the livestock, grains and fruits of the Earth which had been stolen by the witches. If they failed in their task, Thiess opined, then that year's harvest would be bad.[2][3] He told them of how the previous year he had traveled to Hell as a werewolf, and that he had managed to carry as much barley, oats and rye as he could away back to Earth in order to ensure a bountiful harvest.[4] Here, the judges noted an inconsistency in Thiess' claims; he had earlier asserted that he had abandoned his life as a werewolf ten years previously, but here he was admitting to having traveled to Hell as a wolf just that previous year. Under scrutiny, Thiess admitted that he had lied in his former claim.[4]

The Jürgensburg judges then asked Thiess where the souls of the werewolves went when they died, and he responded that they would go to Heaven, whilst the souls of the witches would go to Hell. The judges then questioned this, asking how it was possible for the werewolves' souls to go to Heaven if they were the servants of the Devil. Once more, Thiess reiterated that the werewolves were not servants of the Devil, but of God, and that they undertook their nocturnal journeys to Hell for the good of mankind.[2]

Condemnation

After listening to his account of his nocturnal travels to Hell, the judges became concerned as to whether Thiess was a devout Lutheran or not, and so asked him if he attended church regularly, listened to God's word, regularly prayed and partook of the Lord's Supper. Thiess replied that he did none of these things, claiming that he was too old to understand them.[4]

It was later revealed that aside from his nocturnal journeys, Thiess practiced folk magic for members of the local community, acting as a healer and a charmer. He was known to bless grain and horses, and also knew charms designed to ward off wolves and to stop bleeding. One of these charms involved administering blessed salt in warm beer while reciting the words "Sun and moon go over the sea, fetch back the soul that the devil had taken to hell and give the cattle back life and health which was taken from them." Nowhere did the charm invoke or mention the power of God.[5] For the judges, this blessing was seen as criminal because it encouraged clients to turn away from Christianity, and so they sentenced Thiess to be flogged and banished for life.[5]

Historical interpretations

Initially, the scholarly debate on the issue of the Livonian werewolf was restricted to scholars in the German-speaking world,[6] and it did not appear in English-language overviews of European werewolf beliefs like Montague Summers' The Werewolf (1933).[7] According to Dutch historian Willem de Blécourt, Thiess' case was first brought to the attention of English-speaking scholars by the German anthropologist Hans Peter Duerr (1943–) in his book Dreamtime: Concerning the Boundary between Wilderness and Civilization (1978, English translation 1985).[8] Duerr briefly discussed the Livonian werewolf in a chapter of Dreamtime entitled "Wild Women and Werewolves" in which he dealt with various European folk traditions in which individuals broke social taboos and made mischief in public, arguing that they represented a battle between the forces of chaos and order.[3]

Carlo Ginzburg

The Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg (1939–) discussed the case of the Livonian werewolf in his book The Night Battles: Witchcraft and Agrarian Cults in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (1966, English translation 1983). The Night Battles was devoted primarily to a study of the benandanti folk tradition of Early Modern Friuli in Northeastern Italy, in which local Friulians fell into trance states in which they believed that their spirits left their bodies to battle malevolent witches, in doing so protecting their crops from famine. Ginzburg believed that there were definite similarities between the benandanti and the case of Thiess, noting that both contained "battles waged by means of sticks and blows, enacted on certain nights to secure the fertility of fields, minutely and concretely described."[9]

In Ginzburg's view both the benandanti tradition and Thiess's werewolf tradition represented surviving remants of a shamanistic substratum that had survived Christianization.[10]

In his 1992 paper on the life and work of Ginzburg, the historian John Martin of Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas expressed his support for Ginzburg's hypothesis, claiming that Thiess' role was "almost identical" to that of the benandanti.[11] In a similarly supportive vein, the Hungarian historian Éva Pócs noted the existence of "werewolf magicians" who were aligned to "European shamanistic magicians" in a paper on Hungarian táltos.[12]

Other academics were more cautious than Ginzburg in directly equating the Livonian werewolf with shamanism. Dutch historian Willem de Blécourt noted that in Dreamtime, the German anthropologist Hans Peter Duerr had refrained from making an explicit link between shamans and werewolves, although he did acknowledge the similarities between Thiess and the benandanti.[13]

Willem de Blécourt

In 2007, the Dutch historian Willem de Blécourt of the Huizinga Institute in Amsterdam published a paper in the peer-reviewed journal Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft entitled "A Journey to Hell: Reconsidering the Livonian "Werewolf"".

References

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 De Blécourt 2007. p. 49.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Ginzburg 1983. p. 29.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Duerr 1985. p. 34.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 De Blécourt 2007. p. 50.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 De Blécourt 2007. p. 51.

- ↑ De Blécourt 2007. p. 52. See for instance Von Bruiningk 1924.

- ↑ Summers 1933.

- ↑ De Blécourt 2007. p. 52.

- ↑ Ginzburg 1983. p. 30.

- ↑ Ginzburg 1983. pp. 28–32.

- ↑ Martin 1992. p. 614.

- ↑ Pócs 1989. p. 258.

- ↑ De Blécourt 2007. p. 53.

Bibliography

- Academic books

- Duerr, Hans Peter (1985) [1978]. Dreamtime: Concerning the Boundary between Wilderness and Civilization. Felicitas Goodman (translator). Oxford and New York: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-13375-5.

- Ginzburg, Carlo (1983) [1966]. The Night Battles: Witchcraft and Agrarian Cults in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. John and Anne Tedeschi (translators). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. ISBN 978-0801843860.

- Pócs, Éva (1999) [1997]. Between the Living and the Dead: A Perspective on Witches and Seers in the Early Modern Age. Translated by Szilvia Rédey and Michael Webb. Budapest: Central European Academic Press. ISBN 978-963-9116-19-1.

- Summers, Montague (1933). The Werewolf. London: Routledge.

- Academic papers

- De Blécourt, Willem (2007). "A Journey to Hell: Reconsidering the Livonian "Werewolf"". Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft 2 (1) (University of Pennsylvania Press). pp. 49–67. doi:10.1353/mrw.0.0002.

- Donecker, Stefan (2012). "The Werewolves of Livonia: Lycanthropy and Shape-Changing in Scholarly Texts, 1550–1720". Preternature 1 (2) (Pennsylvania State University Press). pp. 289–322. doi:10.5325/preternature.1.2.0289.

- Eliade, Mircea (1975). "Some Observations on European Witchcraft". History of Religions 14 (3) (The University of Chicago Press). pp. 149–172. doi:10.1086/462721.

- Martin, John (1992). "Journeys to the World of the Dead: The Work of Carlo Ginzburg". Journal of Social History (Fairfax: George University State Press) 25 (3): 613–626. doi:10.1353/jsh/25.3.613.

- Pócs, Éva (1989). "Hungarian Táltos and his European Parallels". Uralic Mythology and Folklore. Mihály Hoppál and Juha Pentikaïnen (editors) (Budapest and Helsinki: Ethnographic Institute of the Hungarian Academy of Science and Finnish Literary Society). pp. 251–276.

- Von Bruiningk, Hermann (1924). "Der Werwolf in Livland". Mitteilungen aus der livländische Geschichte 22. pp. 163–220.