Thermal energy

In thermodynamics, thermal energy refers to the internal energy present in a system by virtue of its temperature.[1] The average translational kinetic energy possessed by free particles in a system of free particles in thermodynamic equilibrium (as measured in the frame of reference of the center of mass of that system) may also be referred to as the thermal energy per particle.[2]

Microscopically, the thermal energy may include both the kinetic energy and potential energy of a system's constituent particles, which may be atoms, molecules, electrons, or particles. It originates from the individually random, or disordered, motion of particles in a large ensemble. In ideal monatomic gases, thermal energy is entirely kinetic energy. In other substances, in cases where some of thermal energy is stored in atomic vibration or by increased separation of particles having mutual forces of attraction, the thermal energy is equally partitioned between potential energy and kinetic energy. Thermal energy is thus equally partitioned between all available degrees of freedom of the particles. As noted, these degrees of freedom may include pure translational motion in gases, rotational motion, vibrational motion and associated potential energies. In general, due to quantum mechanical reasons, the availability of any such degrees of freedom is a function of the energy in the system, and therefore depends on the temperature (see heat capacity for discussion of this phenomenon).

Macroscopically, the thermal energy of a system at a given temperature is proportional to its heat capacity. However, since the heat capacity differs according to whether or not constant volume or constant pressure is specified, or phase changes permitted, the heat capacity cannot be used to define thermal energy unless it is done in such a way as to ensure that only heat gain or loss (not work) makes any changes in the internal energy of the system. Usually, this means specifying the "constant volume heat capacity" of the system so that no work is done. Also the heat capacity of a system for such purposes must not include heat absorbed by any chemical reaction or process.

Differentiation from heat

Heat is the thermal energy transferred across a boundary of one region of matter to another.[3][4] As a process variable, heat is a characteristic of a process, not a property of the system; it is not contained within the boundary of the system.[3] On the other hand, thermal energy is a property of a system, and exists on both sides of a boundary. Classically (see ideal gas), thermal energy is the statistical mean of the microscopic fluctuations of the kinetic energy of the systems' particles, and it is the source and the effect of the transfer of heat across a system boundary.

According to the zeroth law of thermodynamics, heat is exchanged between thermodynamic systems in thermal contact only if their temperatures are different.[5] If heat traverses the boundary in direction into the system, the internal energy change is considered to be a positive quantity, while exiting the system, it is negative. Heat flows from the hotter to the colder system, decreasing the thermal energy of the hotter system, and increasing the thermal energy of the colder system. Then, when the two systems have reached thermodynamic equilibrium, they have the same temperature, and the net exchange of thermal energy vanishes and heat flow ceases. Even after they reach thermal equilibrium, thermal energy continues to be exchanged between systems, but the net exchange of thermal energy is zero, and therefore there is no heat.

After the transfer, the energy transferred by heat is called by other terms, such as thermal energy or latent energy.[6] Although heat often ends up as thermal energy after transfer, it may cause changes other than a change in temperature. For example, the energy may absorbed or released in phase transitions, such as melting or evaporation, which are the gain or loss of a form of potential energy called latent heat.

Thermal energy may be increased in a system by other means than heat, for example when mechanical or electrical work is performed on the system. Heat flow may cause work to be performed on a system by compressing a system's volume, for example. A heat engine uses the movement of thermal energy (heat flow)to do mechanical work. No qualitative difference exists between the thermal energy added by other means. There is also no need in classical thermodynamics to characterize the thermal energy in terms of atomic or molecular behavior. A change in thermal energy induced in a system is the product of the change in entropy and the temperature of the system.

Rather than being itself the thermal energy involved in a transfer, heat is sometimes also understood as the process of that transfer, i.e. heat functions as a verb.

Definitions

Thermal energy is the portion of the thermodynamic or internal energy of a system that is responsible for the temperature of the system.[1][3] The thermal energy of a system scales with its size and is therefore an extensive property. It is not a state function of the system unless the system has been constructed so that all changes in internal energy are due to changes in thermal energy, as a result of heat transfer (not work). Otherwise thermal energy is dependent on the way or method by which the system attained its temperature. Thermal energy can be transformed into and out of other types of energy, and is not generally a conserved quantity.

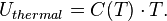

From a macroscopic thermodynamic description, the thermal energy of a system is given by the product of its constant volume specific heat capacity, C(T), and its absolute temperature, T:

The heat capacity is a function of temperature itself, and is typically measured and specified for certain standard conditions and a specific amount of substance (molar heat capacity) or mass units (specific heat capacity). At constant volume (V), CV it is the temperature coefficient of energy.[7] In practice, given a narrow temperature range, for example the operational range of a heat engine, the heat capacity of a system is often constant, and thus thermal energy changes are conveniently measured as temperature fluctuations in the system.

In the microscopical description of statistical physics, the thermal energy is identified with the mechanical kinetic energy of the constituent particles or other forms of kinetic energy associated with quantum-mechanical microstates.

The distinguishing difference between the terms kinetic energy and thermal energy is that thermal energy is the mean energy of disordered, i.e. random, motion of the particles or the oscillations in the system. The conversion of energy of ordered motion to thermal energy results from collisions.[8]

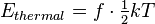

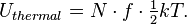

All kinetic energy is partitioned into the degrees of freedom of the system. The average energy of a single particle with f quadratic degrees of freedom in a thermal bath of temperature T is a statistical mean energy given by the equipartition theorem as

where k is the Boltzmann constant. The total thermal energy of a sample of matter or a thermodynamic system is consequently the average sum of the kinetic energies of all particles in the system. Thus, for a system of N particles its thermal energy is[9]

For gaseous systems, the factor f, the number of degrees of freedom, commonly has the value 3 in the case of the monatomic gas, 5 for many diatomic gases, and 7 for larger molecules at ambient temperatures. In general however, it is a function of the temperature of the system as internal modes of motion, vibration, or rotation become available in higher energy regimes.

Uthermal is not the total energy of a system. Physical systems also contains static potential energy (such as chemical energy) that arises from interactions between particles, nuclear energy associated with atomic nuclei of particles, and even the rest mass energy due to the equivalence of energy and mass.

Thermal energy of the ideal gas

Thermal energy is most easily defined in the context of the ideal gas, which is well approximated by a monatomic gas at low pressure. The ideal gas is a gas of particles considered as point objects of perfect spherical symmetry that interact only by elastic collisions and fill a volume such that their mean free path between collisions is much larger than their diameter.

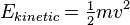

The mechanical kinetic energy of a single particle is

where m is the particle's mass and v is its velocity. The thermal energy of the gas sample consisting of N atoms is given by the sum of these energies, assuming no losses to the container or the environment:

where the line over the velocity term indicates that the average value is calculated over the entire ensemble. The total thermal energy of the sample is proportional to the macroscopic temperature by a constant factor accounting for the three translational degrees of freedom of each particle and the Boltzmann constant. The Boltzmann constant converts units between the microscopic model and the macroscopic temperature. This formalism is the basic assumption that directly yields the ideal gas law and it shows that for the ideal gas, the internal energy U consists only of its thermal energy:

Historical context

In an 1847 lecture entitled On Matter, Living Force, and Heat, James Prescott Joule characterized various terms that are closely related to thermal energy and heat. He identified the terms latent heat and sensible heat as forms of heat each effecting distinct physical phenomena, namely the potential and kinetic energy of particles, respectively.[10] He describes latent energy as the energy of interaction in a given configuration of particles, i.e. a form of potential energy, and the sensible heat as an energy affecting temperature measured by the thermometer due to the thermal energy, which he called the living force.

The origin of heat energy on Earth

Earth's proximity to the Sun is the reason that almost everything near Earth's surface is warm with a temperature substantially above absolute zero.[11] Solar radiation constantly replenishes heat energy that Earth loses into space and a relatively stable state of near equilibrium is achieved. Because of the wide variety of heat diffusion mechanisms (one of which is black-body radiation which occurs at the speed of light), objects on Earth rarely vary too far from the global mean surface and air temperature of 287 to 288 K (14 to 15 °C). The more an object's or system's temperature varies from this average, the more rapidly it tends to come back into equilibrium with the ambient environment.

Thermal energy of individual particles

The term thermal energy is also often used as a property of single particles to designate the kinetic energy of the particles. An example is the description of thermal neutrons having a certain thermal energy, which means that the kinetic energy of the particle is equivalent to the temperature of its surrounding

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Thermal energy entry in Britannica Online

- ↑ Thermal energy entry in Hyperphysics web site

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Robert F. Speyer (2012). Thermal Analysis of Materials. Materials Engineering. Marcel Dekker, Inc. p. 2. ISBN 0-8247-8963-6.

- ↑ Thomas W. Leland, Jr., G. A. Mansoori, ed., Basic Principles of Classical and Statistical Thermodynamics (PDF)

- ↑ For the purpose of distinction, a system is defined to be enclosed by a well-characterized boundary.

- ↑ Frank P. Incorporeal; David P. De Witt (1990). Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 2. ISBN 0-471-51729-1. See box definition: "Heat transfer (or heat) is energy in transit due to a temperature difference." See page 14 for the definition of the thermal component of the thermodynamic internal energy.

- ↑ Hans U. Fuchs (2010). The Dynamics of Heat: A Unified Approach to Thermodynamics and Heat Transfer (2 ed.). Springer. p. 211. ISBN 978-1-4419-7603-1.

- ↑ S. Blundell, K. Blundell (2006). Concepts in Thermal Physics. Oxford University Press. p. 366. ISBN 0-19-856769-3.

- ↑ D.V. Schroeder (1999). An Introduction to Thermal Physics. Addison-Wesley. p. 15. ISBN 0-201-38027-7.

- ↑ J. P. Joule (1884), "Matter, Living Force, and Heat", The Scientific Papers of James Prescott Joule (The Physical Society of London): 274, retrieved 2 January 2013,

I am inclined to believe that both of these hypotheses will be found to hold good,—that in some instances, particularly in the case of sensible heat, or such as is indicated by the thermometer, heat will be found to consist in the living force of the particles of the bodies in which it is induced; whilst in others, particularly in the case of latent heat, the phenomena are produced by the separation of particle from particle, so as to cause them to attract one another through a greater space.

- ↑ The deepest ocean depths (3 to 10 km) are no colder than about 274.7–275.7 K (1.5–2.5 °C). Even the world-record cold surface temperature established on July 21, 1983 at Vostok Station, Antarctica is 184 K (a reported value of −89.2 °C). The residual heat of gravitational contraction left over from earth's formation, tidal friction, and the decay of radioisotopes in earth's core provide insufficient heat to maintain earth's surface, oceans, and atmosphere "substantially above" absolute zero in this context. Also, the qualification of "most-everything" provides for the exclusion of lava flows, which derive their temperature from these deep-earth sources of heat.