Theoretical key

In music theory, a theoretical key or impossible key is a key and scale which exists in theory and practice, but whose corresponding key signature make its notation impractical. Such a key is one whose key signature would contain one or more double-flats or double-sharps.

Double-flats and double-sharps are used in music as accidentals, but they are never placed in the key signature (in music that uses equal temperament), due to notational convention and because reading the music would become unnecessarily difficult.

For example, the key of D♭ minor is not conventionally used in notated music, because its corresponding key signature would contain a B![]() (submediant). An equal-tempered scale of D♭ minor comprises the same notes as the C♯ minor scale. Under equal temperament the scales sound exactly the same; such key pairs are said to be enharmonically equivalent. So the theoretical key of D♭ minor is usually practically notated by a key signature of C♯ minor.

(submediant). An equal-tempered scale of D♭ minor comprises the same notes as the C♯ minor scale. Under equal temperament the scales sound exactly the same; such key pairs are said to be enharmonically equivalent. So the theoretical key of D♭ minor is usually practically notated by a key signature of C♯ minor.

| C♯ minor: | C♯ | D♯ | E | F♯ | G♯ | A | B |

| D♭ minor: | D♭ | E♭ | F♭ | G♭ | A♭ | B | C♭ |

The other option is to use either no key signature or one with single-flats and to provide accidentals as needed for the B![]() s.

s.

Enharmonic equivalence

While a piece of Western music generally has a home key, a passage within it may modulate to another key, which is usually closely related to the home key (in the Baroque and early Classical eras), that is, close to the original around the circle of fifths. When the key is near the top of the circle (a key signature of zero or few accidentals), the notation of both keys is straightforward. But if the home key is near the bottom of the circle (a key signature of many accidentals), and particularly if the new key is on the opposite side (in the late Classical and Romantic eras), it becomes necessary to consider enharmonic equivalence.

In each of the bottom three places on the circle of fifths the two enharmonic equivalents can be notated and so do not classify as 'theoretical keys':

| Major (minor) | Key signature | Major (minor) | Key signature | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (g♯) | 5 sharps | C♭ (a♭) | 7 flats | |

| F♯ (d♯) | 6 sharps | G♭ (e♭) | 6 flats | |

| C♯ (a♯) | 7 sharps | D♭ (b♭) | 5 flats |

The need to consider theoretical keys

However, when a relative key ascends the opposite side of the circle from its home key, then theory suggests that double-sharps and double-flats would have to be incorporated into the notated key signature. The following six keys (which are the parallel major/minor keys of those above) would require one, two or three double-sharps or double-flats:

| Key | Key Signature | Relative key |

|---|---|---|

| D♭ minor | 8 flats (= C♯ minor) | F♭ major (= E major) |

| G♭ minor | 9 flats (= F♯ minor) | B |

| C♭ minor | 10 flats (= B minor) | E |

| G♯ major | 8 sharps (= A♭ major) | E♯ minor (= F minor) |

| D♯ major | 9 sharps (= E♭ major) | B♯ minor (= C minor) |

| A♯ major | 10 sharps (= B♭ major) | F |

For example, pieces in the major mode commonly modulate up a fifth to the dominant; for a key with sharps in the signature this leads to a key whose key signature has an additional sharp. A piece in C♯ which performs this modulation would lead to the theoretical key of G♯, requiring an eighth sharp, meaning an F![]() in place of the F♯ already present. In order to write that passage with a new key signature, it would become necessary to recast the new section using the enharmonically equivalent key signature of A♭ major.

in place of the F♯ already present. In order to write that passage with a new key signature, it would become necessary to recast the new section using the enharmonically equivalent key signature of A♭ major.

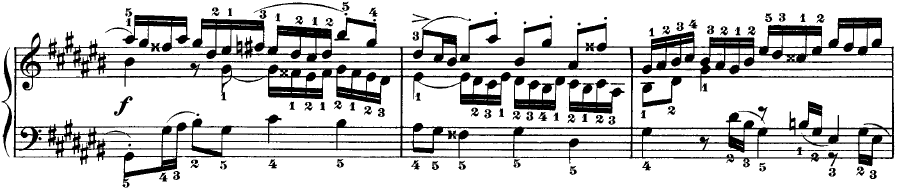

However, such passages are usually notated with the use of accidentals, as in this example from Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier, in G♯ major (the overall key is C♯ major):

Tunings other than twelve-tone equal-temperament

In a different tuning system (for example, 19 tone equal temperament), several keys do require a double-sharp or double-flat in the key signature, and no longer have conventional equivalents: where there are 19 tones in the scale, the key of B![]() major (9 flats) is equivalent to A♯ major (10 sharps). In 17 tone equal temperament and 31 tone equal temperament, keys that are enharmonic in a 12 tone system (for example, C♯ and D♭ minor) may have to be notated completely differently.

major (9 flats) is equivalent to A♯ major (10 sharps). In 17 tone equal temperament and 31 tone equal temperament, keys that are enharmonic in a 12 tone system (for example, C♯ and D♭ minor) may have to be notated completely differently.

See also

| Diatonic scales and keys | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The table indicates the number of sharps or flats in each scale. Minor scales are written in lower case. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||