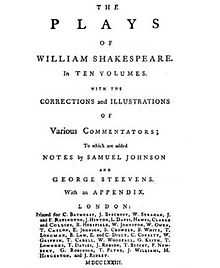

The Plays of William Shakespeare

The Plays of William Shakespeare was an 18th-century edition of the dramatic works of William Shakespeare, edited by Samuel Johnson and George Steevens. Johnson announced his intention to edit Shakespeare's plays in his Miscellaneous Observations on Macbeth (1745), and a full Proposal for the edition was published in 1756. The edition was finally published in 1765.

In the "Preface" to his edition, Johnson justifies trying to determine the original language of the Shakespearean plays. To benefit the reading audience, he added explanatory notes to various passages. Later editors followed Johnson's lead and sought to determine an authoritative text of Shakespeare.

Background

Johnson began reading Shakespeare's plays and poetry when he was a young boy.[1] He would involve himself so closely with the plays that he was once terrified by the Ghost in Hamlet and had to "have people about him".[2] Johnson's fascination with Shakespeare continued throughout his life, and Johnson focused his time on Shakespeare's plays while preparing A Dictionary of the English Language,[3] so it is no wonder that Shakespeare is the most quoted author in it.[4]

Johnson came to believe that there was a problem with the collections of Shakespearean plays that were available during his lifetime. He believed that they lacked authoritativeness, because they:

were transcribed for the players by those who may be supposed to have seldom understood them; they were transmitted by copiers equally unskillful, who still multiplied errors; they were perhaps sometimes mutilated by the actors, for the sake of shortening the speeches; and were at last printed without correction of the press.[5]

Although Johnson was friends with actors such as David Garrick who had performed Shakespeare onstage, he did not believe that performance was vital to the plays, nor did he ever acknowledge the presence of an audience as a factor in the reception of the work.[6] Instead, Johnson believed that the reader of Shakespeare was the true audience of the play.[6]

Furthermore, Johnson believed that later editors both misunderstood the historical context of Shakespeare and his plays, and underestimated the degree of textual corruption that the plays exhibit.[7] He believed that this was because "The style of Shakespeare was in itself perplexed, ungrammatical, and obscure".[8] To correct these problems, Johnson believed that the original works would need to be examined, and this became an issue in his Proposal.[5] Johnson also believed that an edition of Shakespeare could provide him with the income and recognition that he needed.[9] However, a full edition of Shakespeare would require a publisher to make a large commitment of time and money, so Johnson decided to begin by focusing on a single play, Macbeth.[9]

Miscellaneous Observations

Johnson began work on Macbeth to provide a sample of what he thought could be achieved in a new edition of Shakespeare.[7] He got much of his information while working on the Harleian Catalogue, a catalogue of the collection of works and pamphlets owned by Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer.[7] He published this work, along with a commentary on Sir Thomas Hanmer, 4th Baronet's edition of Shakespeare's plays, as Miscellaneous Observations or Miscellaneous Observations on the Tragedy of Macbeth on 6 April 1745 by Edward Cave.[7]

Hanmer produced an edition of Shakespeare's plays for the Clarendon Press in October 1744, and Johnson felt that he could attract more attention to his own work by challenging some of Hanmer's points.[10] Johnson criticised Hanmer for editing Shakespeare's words based on subjective opinion instead of objective fact.[10] In particular, Johnson writes:

He appears to find no difficulty in most of those passages which I have represented as unintelligible, and has therefore passed smoothly over them, without any attempt to alter or explain them... Such harmless industry may surely be forgiven if it cannot be praised; may he therefore never want a monosyllable who can use it with such wonderful dexterity. Rumpature quisquis rumpitur invidia! ("If anyone is going to burst with envy, let him do so!" – Martial)[11]

He then continues:

The rest of this edition I have not read, but, from the little that I have seen, I think it not dangerous to declare that, in my opinion, its pomp recommends it more than its accuracy. There is no distinction made between the ancient reading, and the innovations of the editor; there is no reason given for any of the alterations which are made; the emendations of former editions are adopted without any acknowledgement, and few of the difficulties are removed which have hitherto embarrassed the readers of Shakespeare.[12]

The Miscellaneous Observations contains many of Johnson's early thoughts and theories on Shakespeare.[13] For instance, Johnson thought that there was an uncanny power in Shakespeare's supernatural scenes and wrote, "He that peruses Shakespeare looks round alarmed and starts to find himself alone".[14]

At the end of the work, Johnson announced that he would produce a new edition of Shakespeare:[15]

Proposals for printing a new edition of the plays of William Shakespeare, with notes, critical and explanatory, in which the text will be corrected: the various readings remarked: the conjuectures of former editors examined, and their omissions supplied. By the author of the Miscellaneous Observations on the Tragedy of Macbeth.[12]

In response, Jacob Tonson and his associates, who controlled the copyright of the current edition of Shakespeare, threatened to sue Johnson and Cave in a letter written on 11 April 1745.[16] They did so to protect their new edition, edited by the Shakespeare scholar William Warburton.[15]

Proposal

On 1 June 1756, Johnson reprinted his Miscellaneous Observations but attached his Proposal or Proposals for Printing, by Subscription, the Dramatick Works of William Shakespeare, Corrected and Illustrated. On 2 June 1756, he signed a contract to edit an eight-volume set of Shakespeare's writings including a preface, and on 8 June 1756 Johnson printed his Proposal, now called Proposals for an Edition of Shakespeare.[17] The Proposal sold subscriptions for Johnson's future edition at the cost two guineas, the first paid before and the second upon printing.[18] When Johnson achieved scholarly renown for his A Dictionary of the English Language, Warburton's publishers, Tonson et al., granted him permission to work on Shakespeare.[17]

In the Proposal, Johnson describes the various problems with previous editions of Shakespeare and argues how a new edition, written by himself, would correct these problems.[3] In particular, Johnson promised to "correct what is corrupt, and to explain what is obscure".[19] He would accomplish this by relying on "a careful collation of all the oldest copies" and to read "the same story in the very book which Shakespeare consulted".[20] Unlike other editors who "slight their predecessors", Johnson claimed that "all that is valuable will be adopted from every commentator, that posterity may consider it as including all the rest, and exhibiting whatever is hitherto known of the great father of the English drama".[20] Later in the work, he promised that it would be ready by December 1757.[3]

Johnson was contracted to finish the edition in 18 months but as the months passed, his pace slowed. He told Charles Burney in December 1757 that it would take him until the following March to complete it.[21] Before that could happen, in February 1758 he was arrested again for an unpaid debt of £40.[21] The debt was soon repaid by Tonson, who had contracted Johnson to publish the work; this motivated Johnson to finish the edition to repay the favour.[21] Although it took him another seven years to finish, Johnson completed a few volumes of his Shakespeare to prove his commitment to the project.[21]

Johnson's Shakespeare

Johnson admitted to John Hawkins that "my inducement to it is not love or desire of fame, but the want of money, which is the only motive to writing that I know of."[18] However, the money was not a strong enough motivator and in 1758, partly as a way to avoid having to finish his Shakespeare, Johnson began to write a weekly series, The Idler, which ran from 15 April 1758 to 5 April 1760.[22]

By 1762, Johnson had gained a reputation for being a slow worker. Contemporary poet Charles Churchill teased Johnson for the delay in producing his long-promised edition of Shakespeare: "He for subscribers baits his hook / and takes your cash, but where's the book?"[23] The comments soon stung Johnson into renewed work.[23] It was only in 20 July 1762, when he received the first payment on a government pension of 300 pounds a year, that he no longer had to worry about money and was finally able to dedicate most of his time to finishing the work.[24]

On 10 January 1765, the day after Johnson was introduced to Henry and Hester Thrale, Johnson noted in his diary that he "Corrected a sheet."[25] Afterwards, he began visiting his friend Richard Farmer who was writing his Essay on the Learning of Shakespeare to aid in his completely revising the work.[25] During this time, Johnson added more than 550 notes as he began to revise the work for publication.[25] In June, Johnson advertised that his edition would be published on 1 August 1765.[26] However, he was unable to work on the Preface until August and it was not printed until 29 September.[26] George Steevens volunteered to help Johnson work on the Preface during this time.[26]

Johnson's edition of Shakespeare's plays was finally published on 10 October 1765 as The Plays of William Shakespeare, in Eight Volumes ... To which are added Notes by Sam. Johnson in a printing of 1,000 copies.[27] The edition sold quickly and a second edition was soon printed, with an expanded edition to follow in 1773 and a further revised edition in 1778.[27]

Preface

There are four components to Johnson's Preface to Shakespeare: a discussion of Shakespeare's "greatness" especially in his "portrayal of human nature"; the "faults or weakness" of Shakespeare; Shakespeare's plays in relationship to contemporary poetry and drama; and a history of "Shakespearean criticism and editing down to the mid-1700's" and what his work intends to do.[28]

Johnson begins:

That praises are without reason lavished on the dead, and that the honours due only to excellence are paid to antiquity, is a complaint likely to be always continued by those, who, being able to add nothing to truth, hope for eminence from the heresies of paradox; or those, who, being forced by disappointment upon consolatory expedients, are willing to hope from posterity what the present age refuses, and flatter themselves that the regard which is yet denied by envy, will be at last bestowed by time. Antiquity, like every other quality that attracts the notice of mankind, has undoubtedly votaries that reverence it, not from reason, but from prejudice. Some seem to admire indiscriminately whatever has been long preserved, without considering that time has sometimes co-operated with chance; all perhaps are more willing to honour past than present excellence; and the mind contemplates genius through the shades of age, as the eye surveys the sun through artificial opacity. The great contention of criticism is to find the faults of the moderns, and the beauties of the ancients. While an authour is yet living we estimate his powers by his worst performance, and when he is dead we rate them by his best.To works, however, of which the excellence is not absolute and definite, but gradual and comparative; to works not raised upon principles demonstrative and scientifick, but appealing wholly to observation and experience, no other test can be applied than length of duration and continuance of esteem. What mankind have long possessed they have often examined and compared, and if they persist to value the possession, it is because frequent comparisons have confirmed opinion in its favour. As among the works of nature no man can properly call a river deep or a mountain high, without the knowledge of many mountains and many rivers; so in the productions of genius, nothing can be stiled excellent till it has been compared with other works of the same kind. Demonstration immediately displays its power, and has nothing to hope or fear from the flux of years; but works tentative and experimental must be estimated by their proportion to the general and collective ability of man, as it is discovered in a long succession of endeavours. Of the first building that was raised, it might be with certainty determined that it was round or square, but whether it was spacious or lofty must have been referred to time. The Pythagorean scale of numbers was at once discovered to be perfect; but the poems of Homer we yet know not to transcend the common limits of human intelligence, but by remarking, that nation after nation, and century after century, has been able to do little more than transpose his incidents, new name his characters, and paraphrase his sentiments.

The reverence due to writings that have long subsisted arises therefore not from any credulous confidence in the superior wisdom of past ages, or gloomy persuasion of the degeneracy of mankind, but is the consequence of acknowledged and indubitable positions, that what has been longest known has been most considered, and what is most considered is best understood.[29]

Johnson then introduces Shakespeare:

The poet, of whose works I have undertaken the revision, may now begin to assume the dignity of an ancient, and claim the privilege of established fame and prescriptive veneration. He has long outlived his century, the term commonly fixed as the test of literature merit. Whatever advantages he might once derive from personal allusions, local customs, or temporary opinions, have for many years been lost; and every topic of merriment, or motive of sorrow, which the modes of artificial life afforded him, now only obscure the scenes which they once illuminated. The effects of favour and competition are at an end; the tradition of his friendships and his enmities has perished; his works support no opinion with arguments, nor supply any faction with invectives; they can neither indulge vanity nor gratify malignity; but are read without any other reason than the desire of pleasure, and are therefore praised only as pleasure is obtained; yet, thus unassisted by interest or passion, they have past through variation of taste and changes of manners, and, as they devolved from one generation to another, have received new honours at every transmission.[30]

Plays

Johnson, in his Proposal, said that "the corruptions of the text will be corrected by a careful collation of the oldest copies".[5] Accordingly, Johnson attempted to obtain early texts of the plays but many people were unwilling to lend him their editions out of a fear that they might be destroyed.[5] David Garrick offered Johnson access to his collection of Shakespeare texts but Johnson declined the offer, believing that Garrick would expect preferential treatment in return.[31]

Johnson's strength was to create a set of corresponding notes that allow readers to identify the meaning behind many of Shakespeare's more complicated passages or ones that may have been transcribed incorrectly over time.[31] Including within the notes are occasional attacks upon the rival editors of Shakespeare's works and their editions.[3]

In 1766, Steevens published his own edition of Shakespeare's plays that was "designed to transcend Johnson's in proceeding further towards a sound text", but it lacked the benefit of Johnson's critical notes.[27] The two worked together to create a revised edition of Shakespeare's plays in ten volumes, published in 1773 with additional corrections in 1778.[27] Steevens provided most of the textual work, with Johnson contributing an additional eighty notes.[27]

Critical response

After Johnson was forced to back down from producing his edition of Shakespeare in 1746, his rival editor William Warburton praised Johnson's Miscellaneous Observations as "some critical notes on Macbeth, given as a specimen of a projected edition, and written, as appears, by a man of parts and genius".[15] Years later, Edmond Malone, an important Shakespearean scholar and friend of Johnson's, said that Johnson's "vigorous and comprehensive understanding threw more light on his authour than all his predecessors had done",[5] and that the Preface was "the finest composition in our language".[32] Adam Smith said that the Preface was "the most manly piece of criticism that was ever published in any country."[32]

In 1908, Walter Raleigh claimed that Johnson helped the reader to "go straight to Shakespeare's meaning, while the philological and antiquarian commentators kill one another in the dark."[33] Raleigh then admitted that he "soon falls into the habit, when he meets with an obscure passage, of consulting Johnson's note before the others."[33] T. S. Eliot wrote that "no poet can ask more of posterity than to be greatly honoured by the great; and Johnson's words about Shakespeare are great honour".[34]

Walter Jackson Bate, in his 1977 biography on Johnson, wrote:

the edition of Shakespeare – viewed with historical understanding of what it involved in 1765 – could seem a remarkable feat; and we are not speaking of just the great Preface To see it in perspective, we have only to remind ourselves what Johnson brought to it – an assemblage of almost every qualification we should ideally like to have brought to this kind of work with the single exception of patience... Operating in and through these qualities was his own extensive knowledge of human nature and life. No Shakespearean critic or editor has ever approached him in this respect.[35]

John Wain, another of Johnson's biographers, claimed, "There is no better statement of the reason why Shakespeare needs to be edited, and what aims an editor can reasonably set himself" than Johnson's Proposal.[3]

Notes

- ↑ Wain 1974, p. 29

- ↑ Piozzi 1951, p. 151

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Wain 1974, p. 194

- ↑ Wain 1974, p. 188

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Bate 1977, p. 396

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Wain 1974, p. 146

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Bate 1977, p. 227

- ↑ Wain 1974, p. 138

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Wain 1974, p. 125

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Wain 1974, p. 126

- ↑ Wain 1974, pp. 126–127

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Wain 1974, p. 127

- ↑ Lane 1975, p. 103

- ↑ Johnson 1968

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Bate 1977, p. 228

- ↑ Wain 1974, p. 128

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Bate 1977, p. 330

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Lane 1975, p. 138

- ↑ Yung et al. 1984, p. 86

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Yung et al. 1984, p. 87

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Bate 1977, p. 332

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 334

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Bate 1977, p. 391

- ↑ Lane 1975, p. 147

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Bate 1977, p. 393

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Bate 1977, p. 394

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 Bate 1977, p. 395

- ↑ Bate 1977, pp. 398–399

- ↑ Johnson 1973, p. 149

- ↑ Johnson 1973, p. 150

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Bate 1977, p. 397

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Bate 1977, p. 399

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Raleigh 1908, p. xvi

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 401

- ↑ Bate 1977, pp. 395–396

References

- Bate, Walter Jackson (1977), Samuel Johnson, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, ISBN 0-15-179260-7.

- Johnson, Samuel (1973), Wain, John, ed., Johnson as Critic, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-7100-7564-2.

- Johnson, Samuel (1968), Sherbo, Arthur, ed., The Yale edition of the works of Samuel Johnson. Vol. 7, Johnson on Shakespeare, New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-00605-5.

- Lane, Margaret (1975), Samuel Johnson & his World, New York: Harpers & Row Publishers, ISBN 0-06-012496-2.

- Piozzi, Hester (1951), Balderson, Katharine, ed., Thraliana: The Diary of Mrs. Hester Lynch Thrale (Later Mrs. Piozzi) 1776–1809, Oxford: Clarendon, OCLC 359617.

- Raleigh, Walter (1908), Johnson on Shakespeare, London: Oxford University Press, OCLC 10923457.

- Wain, John (1974), Samuel Johnson, New York: Viking Press, OCLC 40318001.

- Yung, Kai Kin; Wain, John; Robson, W. W.; Fleeman, J. D. (1984), Samuel Johnson, 1709–84, London: Herbert Press, ISBN 0-906969-45-X.

External links

- Preface to his Edition of Shakespeare's Plays (1765), Full text, University of Toronto.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.png)