The Picture of Dorian Gray

|

The Picture of Dorian Gray was first published in the July 1890 issue of "Lippincott's Monthly Magazine". | |

| Author | Oscar Wilde |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Philosophical fiction |

| Publisher | Lippincott's Monthly Magazine |

Publication date | 1890 |

| Media type | |

| OCLC | 53071567 |

| 823/.8 22 | |

| LC Class | PR5819.A2 M543 2003 |

The Picture of Dorian Gray is an 1891 philosophical novel by writer and playwright Oscar Wilde. First published as a complete story in the July 1890 issue of Lippincott's Monthly Magazine,[1] the editors feared the story was indecent, and without Wilde's knowledge, deleted five hundred words before publication. Despite that censorship, The Picture of Dorian Gray offended the moral sensibilities of British book reviewers, some of whom said that Oscar Wilde merited prosecution for violating the laws guarding the public morality. In response, Wilde aggressively defended his novel and art in correspondence with the British press.

Wilde revised and expanded the magazine edition of The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890) for publication as a novel; the book edition (1891) featured an aphoristic preface — an apologia about the art of the novel and the reader. The content, style, and presentation of the preface made it famous in its own literary right, as social and cultural criticism. In April 1891, the editorial house Ward, Lock and Company published the revised version of The Picture of Dorian Gray.[2]

The only novel written by Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray exists in two versions, the 1890 magazine edition (in 13 Chapters) as submitted to Lippincott's Monthly Magazine, and the 1891 book edition (in 20 Chapters).[3] As literature of the 19th century, The Picture of Dorian Gray is an example of Gothic fiction with strong themes interpreted from the legendary Faust.[4]

Summary

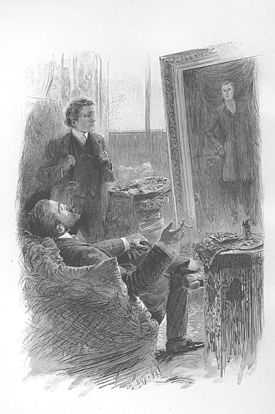

Dorian Gray is the subject of a full-length portrait in oil by Basil Hallward, an artist who is impressed and infatuated by Dorian's beauty; he believes that Dorian’s beauty is responsible for the new mode in his art as a painter. Through Basil, Dorian meets Lord Henry Wotton, and he soon is enthralled by the aristocrat's hedonistic worldview: that beauty and sensual fulfilment are the only things worth pursuing in life.

Understanding that his beauty will fade, Dorian expresses the desire to sell his soul, to ensure that the picture, rather than he, will age and fade. The wish is granted, and Dorian pursues a libertine life of varied and amoral experiences; all the while his portrait ages and records every soul-corrupting sin.[5]

Plot

The Picture of Dorian Gray begins on a beautiful summer day in Victorian era England, where Lord Henry Wotton, an opinionated man, is observing the sensitive artist Basil Hallward painting the portrait of Dorian Gray, a handsome young man who is Basil's ultimate muse. While sitting for the painting, Dorian listens to Lord Henry espousing his hedonistic world view, and begins to think that beauty is the only aspect of life worth pursuing. This prompts Dorian to wish that the painted image of himself would age in his stead.

Under the hedonist influence of Lord Henry, Dorian fully explores his sensuality. He discovers the actress Sibyl Vane, who performs Shakespeare plays in a dingy, working-class theatre. Dorian approaches and courts her, and soon proposes marriage. The enamoured Sibyl calls him "Prince Charming", and swoons with the happiness of being loved, but her protective brother, James, a sailor, warns that if "Prince Charming" harms her, he will kill Dorian Gray.

Dorian invites Basil and Lord Henry to see Sibyl perform in Romeo and Juliet. Sibyl, whose only knowledge of love was love of the theatre, foregoes her acting career for the experience of true love with Dorian Gray. Disheartened at her quitting the stage, Dorian rejects Sibyl, telling her that acting was her beauty; without that, she no longer interests him. On returning home, Dorian notices that the portrait has changed; his wish has been realised, and the man in the portrait bears a subtle sneer of cruelty.

Conscience-stricken and lonely, Dorian decides to reconcile with Sibyl, but he is too late, as Lord Henry informs him that Sibyl killed herself by swallowing prussic acid. Dorian then understands that, where his life is headed, lust and good looks shall suffice. In the following eighteen years, Dorian experiments with every vice, influenced by a morally poisonous French novel, a gift received from the decadent Lord Henry Wotton.

[The narrative does not reveal the title of the French novel, but, at trial, Wilde said that the novel Dorian Gray read was À Rebours ('Against Nature', 1884), by Joris-Karl Huysmans.[6]]

One night, before leaving for Paris, Basil goes to Dorian's house to ask him about rumours of his self-indulgent sensualism. Dorian does not deny his debauchery, and takes Basil to a locked room to see the portrait, made hideous by Dorian's corruption. In anger, Dorian blames his fate on Basil, and stabs him dead. Dorian then calmly blackmails an old friend, the chemist Alan Campbell, into destroying the body of Basil Hallward by nitric acid.

To escape the guilt of his crime, Dorian goes to an opium den, where James Vane is unknowingly present. Upon hearing someone refer to Dorian as "Prince Charming", James seeks out and tries to shoot Dorian dead. In their confrontation, Dorian deceives James into believing that he is too young to have known Sibyl, who killed herself eighteen years earlier, as his face is still that of a young man. James relents and releases Dorian, but is then approached by a woman from the opium den who reproaches James for not killing Dorian. She confirms that the man was Dorian Gray and explains that he has not aged in eighteen years; understanding too late, James runs after Dorian, who has gone.

One evening, during dinner at home, Dorian spies James stalking the grounds of the house. Dorian fears for his life. Days later, during a shooting party, one of the hunters accidentally shoots and kills James Vane who was lurking in a thicket. On returning to London, Dorian tells Lord Henry that he will be good from then on; his new probity begins with not breaking the heart of the naïve Hetty Merton, his current romantic interest. Dorian wonders if his new-found goodness has reverted the corruption in the picture, but sees only an uglier image of himself. From that, Dorian understands that his true motives for the self-sacrifice of moral reformation were the vanity and curiosity of his quest for new experiences.

Deciding that only full confession will absolve him of wrongdoing, Dorian decides to destroy the last vestige of his conscience. Enraged, he takes the knife with which he murdered Basil Hallward, and stabs the picture. The servants of the house awaken on hearing a cry from the locked room; on the street, passers-by who also heard the cry fetch the police. On entering the locked room, the servants find an unknown old man, stabbed in the heart, his face and figure withered and decrepit. The servants identify the disfigured corpse by the rings on his fingers to belong to their master; beside him is the picture of Dorian Gray, reverted to its original beauty.

Characters

Oscar Wilde said that, in the novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), three of the characters were reflections of himself:

Basil Hallward is what I think I am: Lord Henry is what the world thinks me: Dorian is what I would like to be — in other ages, perhaps.[7]

- The characters of the story are

- Dorian Gray — a handsome, narcissistic young man enthralled by Lord Henry's "new" hedonism. He indulges in every pleasure (moral and immoral) which life eventually leads to death.

- Basil Hallward — a deeply moral man, the painter of the portrait, and infatuated with Dorian, whose patronage realises his potential as an artist. The picture of Dorian Gray is Basil's masterpiece.

- Lord Henry "Harry" Wotton — an imperious aristocrat and a decadent dandy who espouses a philosophy of self-indulgent hedonism. Initially Basil's friend, he neglects him for Dorian's beauty. The character of witty Lord Harry is a critique of Victorian culture at the Fin de siècle — of Britain at the end of the 19th century. Lord Harry's libertine world view corrupts Dorian, who then successfully emulates him. To the aristocrat Harry, the observant artist Basil says, "You never say a moral thing, and you never do a wrong thing."

- Sibyl Vane — a talented actress and singer, she is the poor, beautiful girl with whom Dorian falls in love. Her love for Dorian ruins her acting ability, because she no longer finds pleasure in portraying fictional love as she is now experiencing real love in her life. She kills herself on learning that Dorian no longer loves her; at that, Lord Henry likens her to Ophelia, in Hamlet.

- James Vane — Sibyl's brother, a sailor who leaves for Australia. He is very protective of his sister, especially as their mother cares only for Dorian's money. Believing that Dorian means to harm Sybil, James hesitates to leave, and promises vengeance upon Dorian if any harm befalls her. After Sibyl's suicide, James becomes obsessed with killing Dorian, and stalks him, but a hunter accidentally kills James. The brother's pursuit of vengeance upon the lover (Dorian Gray), for the death of the sister (Sybil) parallels that of Laertes vengeance against Prince Hamlet.

- Alan Campbell — chemist and one-time friend of Dorian who ended their friendship when Dorian's libertine reputation devalued such a friendship. Dorian blackmails Alan into destroying the body of the murdered Basil Hallward; Campbell later shoots himself dead.

- Lord Fermor — Lord Henry's uncle, who tells his nephew, Lord Henry Wotton, about the family lineage of Dorian Gray.

- Victoria, Lady Wotton — Lord Henry's wife, whom he treats disdainfully; she divorces him.

Themes and motifs

Aestheticism and duplicity

The greatest theme in The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891) is Aestheticism and its conceptual relation to living a double life. Throughout the story, the narrative presents aestheticism as an absurd abstraction, which disillusions more than it dignifies the concept of Beauty. Despite Dorian being a hedonist when Basil accuses him of making a “by-word” of the name of Lord Henry's sister, Dorian curtly replies, “Take care, Basil. You go too far. . .”; thus, in Victorian society, public image and social standing do matter to Dorian.[8] Yet, Wilde highlights the protagonist's hedonism: Dorian enjoyed "keenly the terrible pleasure of a double life", by attending a high-society party only twenty-four hours after committing a murder.[8]

Moral duplicity and self-indulgence are evident in Dorian’s patronising the opium dens of London. Wilde conflates the images of the upper-class man and lower-class man in Dorian Gray, a gentleman slumming for strong entertainment in the poor parts of London town. Lord Henry philosophically had earlier said to him that: “Crime belongs exclusively to the lower orders . . . I should fancy that crime was to them what art is to us, simply a method of procuring extraordinary sensations” — implying that Dorian is two men, a refined aesthete and a coarse criminal. That authorial observation is a thematic link to the double life recounted in The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), by Robert Louis Stevenson, a novella admired by Oscar Wilde.[1]

Allusions

The Republic

In Book 2 of Plato's The Republic, Glaucon and Adeimantus present the myth of the Ring of Gyges, by means of which Gyges made himself invisible. They then ask Socrates, “If one came into possession of such a ring, why should he act justly?” Socrates replies that although no one can see one's body, the soul is disfigured by the evils one commits. The disfigured and corrupted soul (antithesis of the beautiful soul) is imbalanced and disordered, and, in itself, is undesirable, regardless of any advantage derived from acting unjustly. The picture of Dorian Gray is the means by which other people, such as his friend Basil Hallward, may see Dorian's distorted soul.

Tannhäuser

Dorian attends a performance of Tannhäuser, by Richard Wagner, and the narrative identifies him with the protagonist of the opera. Disruptive beauty is the thematic resemblance between the opera and The Picture of Dorian Gray. Based upon a mediaeval historical figure, Tannhäuser is a singer whose art is so beautiful that Venus becomes enamoured of him. The Roman goddess of love then offers him eternal life with her in the Venusberg, and he accepts; yet, Tannhäuser becomes dissatisfied with life in the Venusberg, and returns to the harsh reality of the mortal world. After participating in a singing contest, Tannhäuser is censured for the sensuality of his art; eventually, he dies searching for repentance and the love of a good woman.

Faust

About the literary hero, the author Oscar Wilde said, “in every first novel the hero is the author as Christ or Faust.”[9] As in the legend of Faust, in The Picture of Dorian Gray a temptation (ageless beauty) is placed before the protagonist, which he indulges. In each story, the protagonist entices a beautiful woman to love him, and then destroys her life. In the preface to the novel (1891), Wilde said that the notion behind the tale is “old in the history of literature”, but was a thematic subject to which he had “given a new form”.[10]

Unlike the academic Faust, the gentleman Dorian makes no deal with the Devil, who is represented by the cynical hedonist Lord Henry, who presents the temptation that will corrupt the virtue and innocence that Dorian possesses at the start of the story. Throughout, Lord Henry appears unaware of the effect of his actions upon the young man; and so frivolously advises Dorian, that “the only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it. Resist it, and your soul grows sick with longing.”[11] As such, the devilish Lord Henry is “leading Dorian into an unholy pact, by manipulating his innocence and insecurity.”[12]

Shakespeare

In the preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), Wilde speaks of the sub-human Caliban character from The Tempest. When Dorian tells Lord Henry about his new love Sibyl Vane, he mentions the Shakespeare plays in which she has acted, and refers to her by the name of the heroine of each play. Later, Dorian speaks of his life by quoting Hamlet, a privileged character who impels his girlfriend (Ophelia) to suicide, and prompts her brother (Laertes) to swear mortal revenge.

Joris-Karl Huysmans

The anonymous “poisonous French novel” that leads Dorian to his fall is a thematic variant of À rebours (1884), by Joris-Karl Huysmans. In the biography, Oscar Wilde (1989), the literary critic Richard Ellmann said that:

Wilde does not name the book, but at his trial he conceded that it was, or almost [was], Huysmans's À rebours . . . to a correspondent, he wrote that he had played a ‘fantastic variation’ upon À rebours, and [that] someday must write it down. The references in Dorian Gray to specific chapters are deliberately inaccurate.[13]

Literary significance

Publication history

The Picture of Dorian Gray originally was a short novel submitted to Lippincott's Monthly Magazine for serial publication. In 1889, J. M. Stoddart, an editor for Lippincott, was in London to solicit short novels to publish in the magazine. On 30 August 1889, Stoddart dined with Oscar Wilde, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and T. P. Gill [14] at the Langham Hotel, and commissioned short novels from each writer.[15] Conan Doyle promptly submitted The Sign of the Four (1890) to Stoddart, but Wilde was more dilatory; Conan Doyle's second Sherlock Holmes novel was published in the February 1890 edition of Lippincott's Monthly Magazine, yet Stoddart did not receive Wilde's manuscript for The Picture of Dorian Gray until 7 April 1890, nine months after having commissioned the novel from him.[15]

The literary merits of The Picture of Dorian Gray impressed Stoddart, but, as an editor, he told the publisher, George Lippincott, "in its present condition there are a number of things an innocent woman would make an exception to. . . ."[15] Among the pre-publication deletions that Stoddart and his editors made to the text of Wilde's original manuscript were: (i) passages alluding to homosexuality and to homosexual desire; (ii) all references to the fictional book title Le Secret de Raoul and its author, Catulle Sarrazin; and (iii) all “mistress” references to Gray's lovers, Sibyl Vane and Hetty Merton.[15]

The Picture of Dorian Gray was published on 20 June 1890, in the July issue of Lippincott's Monthly Magazine. British reviewers condemned the novel’s immorality, and said condemnation was so controversial that the W H Smith publishing house withdrew every copy of the July 1890 issue of “Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine” from its bookstalls in railway stations.[15] Consequent to the harsh criticism of the 1890 magazine edition, Wilde ameliorated the homoerotic references, in order to simplify the moral message of the story.[15] In the magazine edition (1890), Basil tells Lord Henry how he “worships” Dorian, and begs him not to “take away the one person that makes my life absolutely lovely to me.” In the magazine edition, Basil concentrates upon love, whereas, in the book edition (1891), Basil concentrates upon his art, saying to Lord Henry, “the one person who gives my art whatever charm it may possess: my life as an artist depends on him.” The magazine edition of The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890) was expanded from thirteen to twenty chapters; and the magazine edition’s final chapter was divided into two chapters, the nineteenth and twentieth chapters of the book edition of The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891). Wilde’s textual additions were about "fleshing out of Dorian as a character" and providing details of his ancestry that made his “psychological collapse more prolonged and more convincing.”[16]

The introduction of the James Vane character to the story develops the socio-economic background of the Sibyl Vane character, thus emphasising Dorian's selfishness and foreshadowing James’s accurate perception of the essentially immoral character of Dorian Gray; thus, he correctly deduced Dorian’s dishonourable intent towards Sybil. The sub-plot about James Vane's dislike of Dorian gives the novel a Victorian tinge of class struggle. With such textual changes, Oscar Wilde meant to diminish the moralistic controversy about the novel The Picture of Dorian Gray.

Preface

Consequent to the harsh criticism of the magazine edition of the novel, the textual revisions to The Picture of Dorian Gray included a preface in which Wilde addressed the criticisms and defend the reputation of his novel.[17] To communicate how the novel should be read, in the Preface, Wilde explains the role of the artist in society, the purpose of art, and the value of beauty. It traces Wilde's cultural exposure to Taoism and to the philosophy of Chuang Tsǔ (Zhuang Zhou). Earlier, before writing the preface, Wilde had written a book review of Herbert Giles’s translation of the work of Zhuang Zhou. The preface was first published in the 1891 edition of the novel; nonetheless, by June 1891, Wilde was defending The Picture of Dorian Gray against accusations that it was a bad book.[18]

In the essay The Artist as Critic, Oscar Wilde said that:

The honest ratepayer and his healthy family have no doubt often mocked at the dome-like forehead of the philosopher, and laughed over the strange perspective of the landscape that lies beneath him. If they really knew who he was, they would tremble. For Chuang Tsǔ spent his life in preaching the great creed of Inaction, and in pointing out the uselessness of all things.[19]

Criticism

In the 19th. century, the critical reception of the novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890) was poor. The book critic of The Irish Times said, The Picture of Dorian Gray was "first published to some scandal."[20] Such book reviews achieved for the novel a “certain notoriety for being ‘mawkish and nauseous’, ‘unclean’, ‘effeminate’ and ‘contaminating’.”[21] Such moralistic scandal arose from the novel's homoeroticism, which offended the sensibilities (social, literary, and aesthetic) of Victorian book critics. Yet, most of the criticism was personal, attacking Wilde for being a hedonist with a distorted view of conventional morality of Victorian Britain. In the 30 June 1890 issue, the Daily Chronicle the book critic said that Wilde's novel contains “one element . . .which will taint every young mind that comes in contact with it.” In the 5 July 1890 issue, of the Scots Observer, the reviewer asked, “Why must Oscar Wilde ‘go grubbing in muck-heaps?’ “ In response to such criticism, Wilde obscured the homoeroticism of the story and expanded the personal background of the characters.[22]

Textual revisions

After the initial publication of the magazine edition of The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), Wilde expanded the text from 13 to 20 chapters and obscured the homoerotic themes of the story.[23] In the novel version of The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), chapters 3, 5, and 15 to 18, inclusive, are new; and chapter 13 of the magazine edition was divided, and became chapters 19 and 20 of the novel edition.[24] In 1895, at his trials, Oscar Wilde said he revised the text of The Picture of Dorian Gray, because of letters sent to him, by the cultural critic Walter Pater.[25]

Passages revised for the novel

- (Basil about Dorian) "He has stood as Paris in dainty armour, and as Adonis with huntsman's cloak and polished boar-spear. Crowned with heavy lotus-blossoms, he has sat on the prow of Adrian's barge, looking into the green, turbid Nile. He has leaned over the still pool of some Greek woodland, and seen in the water's silent silver the wonder of his own beauty."

- (Lord Henry describes “fidelity”) "It has nothing to do with our own will. It is either an unfortunate accident, or an unpleasant result of temperament."

- "You don't mean to say that Basil has got any passion or any romance in him?" / "I don't know whether he has any passion, but he certainly has romance," said Lord Henry, with an amused look in his eyes. / "Has he never let you know that?" / "Never. I must ask him about it. I am rather surprised to hear it."

- (Basil Hallward described) "Rugged and straightforward as he was, there was something in his nature that was purely feminine in its tenderness."

- (Basil to Dorian) "It is quite true that I have worshipped you with far more romance of feeling than a man usually gives to a friend. Somehow, I had never loved a woman. I suppose I never had time. Perhaps, as Harry says, a really grande passion is the privilege of those who have nothing to do, and that is the use of the idle classes in a country."

- (Basil confronts Dorian) "Dorian, Dorian, your reputation is infamous. I know you and Harry are great friends. I say nothing about that now, but surely you need not have made his sister's name a by-word." (The first part of this passage was deleted from the 1890 magazine text; the second part of the passage was inserted to the 1891 novel text.)

Passages added to the novel

- "Each class would have preached the importance of those virtues, for whose exercise there was no necessity in their own lives. The rich would have spoken on the value of thrift, and the idle grown eloquent over the dignity of labour."

- "A grande passion is the privilege of people who have nothing to do. That is the one use of the idle classes of a country. Don't be afraid."

- "Faithfulness! I must analyse it some day. The passion for property is in it. There are many things that we would throw away, if we were not afraid that others might pick them up."

The uncensored edition

In 2011, the Belknap Press published The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. The edition includes text that was deleted by JM Stoddart, Wilde's initial editor, before the story's publication in "Lippincott's Monthly Magazine" in 1890.[26][27][28][29]

Adaptations

Modern variants

In Ireland, for the Dublin “One City, One Book” literary festival, The Picture of Dorian Gray was the "Book of 2010”.[30]

Big Finish Productions published the audio-drama series The Confessions of Dorian Gray (2013) based on the premise that Oscar Wilde based The Picture of Dorian Gray on a real man; the actor Alexander Vlahos portrays Dorian Gray.[31] An adaptation of the The Picture of Dorian Gray, by David Llewellyn, directed by Scott Handcock, and with Alexander Vlahos, as Dorian Gray; it was released in August 2013.[32]

In 2014, the parodical comedy duo Lip Service released a stage play "The Picture of Doreen Gray" satirising the main themes of the original[33]

Editions

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Wordsworth Classics 1992, ISBN 1-85326-015-0

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Modern Library 1992, ISBN 978-0-679-60001-5

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Penguin Classics 1986, ISBN 0-14-043187-X

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Tor 1999, ISBN 0-8125-6711-0

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Books, Inc. 1994

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Broadview Press 1998, ISBN 978-1-55111-126-1

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Barnes and Noble Classics 2003, ISBN 978-1-59308-025-9

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Macmillan Readers 2005, ISBN 978-0-230-02922-4

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Macmillan Readers 2005 (with CD pack), ISBN 978-1-4050-7658-6

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Penguin Classics 2006, ISBN 978-0-14-144203-7

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oxford World's Classics 2006, ISBN 978-0-19-280729-8

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Dalmatian Press Classics 2007, ISBN 978-1-4037-3908-7

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Four Corners Books 2007, ISBN 978-0-9545025-4-6

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oneworld Classics 2008, ISBN 978-1-84749-018-6

- The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition, Belknap Press 2011, ISBN 978-0-674-05792-0

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Illustrated Editions CO., INC. 1931 Illustrated by Lui Trugo.[34]

- The Picture of Dorian Gray , The Folio Society 2012, illustrated by Emma Chichester Clark

- The Uncensored Picture of Dorian Gray, Belknap Press 2011, ISBN 978-0-674-06631-1

- The Picture of Dorian Gray Critical Edition: Original Unexpurgated 1890, 13-Chapter Version, CreateSpace 2015, ISBN 978-1-5089-9821-1

See also

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Dorian Gray syndrome

- List of cultural references in The Picture of Dorian Gray

- The Happy Hypocrite – a thematic inversion of The Picture of Dorian Gray

Footnotes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 The Picture of Dorian Gray (Penguin Classics) – Introduction

- ↑ Notes on The Picture of Dorian Gray – An overview of the text, sources, influences, themes, and a summary of The Picture of Dorian Gray

- ↑ Good Reason radio show, "The Censorship of 'Dorian Gray' "

- ↑ Ghost and Horror Fiction – a website about ghost and horror fiction from the 19th century onwards. (retrieved 30 July 2006)

- ↑ The Picture of Dorian Gray (Project Gutenberg 20-chapter version), line 3479 et seq. in plain text (Chapter VII).

- ↑ Oscar Wilde: Art and Morality (Illustrated Edition), ed. by Stuart Mason (Fairford: Echo Library, 2011), p. 63

- ↑ The Modern Library – a synopsis of the novel coupled with a short biography of Oscar Wilde. (retrieved 3 November 2009)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 The Picture of Dorian Gray (Penguin Classics) – Chapter XI

- ↑ The Picture of Dorian Gray – Google Books. Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ↑ The Picture of Dorian Gray (Penguin Classics) – Preface

- ↑ The Picture of Dorian Gray (Penguin Classics) – Chapter II

- ↑ The Picture of Dorian Gray – a summary of and a commentary on Chapter II of The Picture of Dorian Gray (retrieved 29 July 2006)

- ↑ Ellmann, Oscar Wilde (Vintage, 1988), p. 316

- ↑ Oscar Wilde, Selected Letters ed Hart-Davis, R Oxford University Press, 1979,p95

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 Frankel, Nicholas (2011) [1890]. "Textual Introduction". In Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press (Harvard University Press). pp. 38–64. ISBN 978-0-674-05792-0.

- ↑ The Picture of Dorian Gray (Penguin Classics) – A Note on the Text

- ↑ GraderSave: ClassicNote – a summary and analysis of the book and its preface (retrieved 5 July 2006)

- ↑ The Letters of Oscar Wilde, Merlin Holland and Rupert Hart-Davis, eds., Henry Holt (2000), ISBN 0-8050-5915-6; and The Artist as Critic, Richard Ellmann, ed., University of Chicago (1968), ISBN 0-226-89764-8 – containing Wilde's book review of Giles's translation, and Chuang Tsǔ (Zhuang Zhou) is incorrectly identified as Confucius. Wilde's book review of Giles's translation was published in The Speaker magazine of 8 February 1890.

- ↑ Ellmann, The Artist as Critic p. 222.

- ↑ Battersby, Eileen (7 April 2010). "Wilde's Portrait of Subtle Control". Irish Times. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ↑ The Modern Library – a synopsis of the novel and a short biography of Oscar Wilde. (retrieved 6 July 2006)

- ↑ CliffsNotes:The Picture of Dorian Gray – an introduction and overview the book (retrieved 5 July 2006)

- ↑ Symon, Evan V. (January 14, 2013). "10 Deleted Chapters that Transformed Famous Books". listverse.com.

- ↑ "Differences between the 1890 and 1891 editions of "Dorian Gray"". Github.io. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ↑ Lawler, Donald L., "An Inquiry into Oscar Wilde's Revisions of 'The Picture of Dorian Gray' " (New York: Garland, 1988)

- ↑ "The Picture of Dorian Gray – Oscar Wilde, Nicholas Frankel – Harvard University Press". Hup.harvard.edu. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ↑ Alison Flood (27 April 2011). "Uncensored Picture of Dorian Gray published | Books | guardian.co.uk". London: Guardian. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ↑ "Thursday: The Uncensored "Dorian Gray"". The Washington Post. 4 April 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ↑ Wilde, Oscar (2011) [1890]. Frankel, Nicholas, ed. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press (Harvard University Press). ISBN 978-0-674-05792-0.

- ↑ "2010 | Dublin: One City, One Book". Dublinonecityonebook.ie. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ↑ http://www.bigfinish.com/ranges/v/the-confessions-of-dorian-gray

- ↑ http://www.bigfinish.com/releases/v/the-picture-of-dorian-gray-927?range=68

- ↑ http://www.yorkpress.co.uk/leisure/theatre/11604741.TakeOver_Festival__Lip_Service_in_The_Picture_Of_Doreen_Gray__Monday__Metal_Rabbit_in_Jonny_Got_His_Gun__York_Theatre_Royal_/?ref=la

- ↑ "The picture of Dorian Gray. Illustrated by Lui Trugo". WorldCat. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Picture of Dorian Gray |

- Replica of the 1890 Edition & Critical Edition at University of Victoria

- The Picture of Dorian Gray to read on line on bibliomania site.

- The Picture of Dorian Gray (13-chapter version) at Project Gutenberg

- The Picture of Dorian Gray (20-chapter version) at Project Gutenberg

- Audioversion at LibriVox

- The Picture of Dorian Gray title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- The Picture of Dorian Gray study guide, themes, quotes, literary devices, character analyses, teacher resources

- The Picture of Dorian Gray at Odeon Theatre, Bucharest, Romania.

- Photo Gallery. The Picture of Dorian Gray. Odeon Theatre.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||